Visionary plastic surgeon aims to take nation’s medical innovations to the world stage, using the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area as a launchpad and igniting hopes for millions of people with body deformities. William Xu reports from Hong Kong.

Editor’s note: The future belongs to those who dare to shape it. In this series, China Daily highlights the bold thinkers and doers transforming industries and breaking barriers. Meet Guo Shuzhong, a pioneer in ear reconstruction surgery, who is transforming lives and bringing hope to people with bodily deformities.

Toiling under the operating room’s shadowless lamp, Guo Shuzhong doesn’t look like a surgeon.

Armed with a carving knife and pieces of human rib cartilage, he works not as a doctor mending flesh, but an artist reviving a still life.

Sitting in front of a side table, Guo’s hands slice the cartilages that have just been removed from a patient on the operating table a meter away, and bend them into the appropriate curvature before sewing and fixing them with titanium thread. After all the parts are curved, Guo uses knives and scissors to make the final adjustments. Some 40 minutes later, a framework that looks and feels almost like an authentic ear takes shape.

Restoring hope

Over the past three decades, Guo has implanted cartilage-turned-ears on thousands of children with incomplete ears, bringing hope to many families. Now, with his new career in Shenzhen on firm ground, the 62-year-old plastic surgeon wants to help more children in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and beyond, pass on the skills to young doctors, and harness the 11-city cluster as a stage for showcasing China’s medical innovations worldwide.

“It’s hard for people with normally developed ears to feel the pain and inconveniences they (kids with incomplete ears) suffer,” says Guo, who is the chief plastic surgeon at Shenzhen New Frontier United Family Hospital.

Microtia — a congenital anomaly of the outer ear that affects about one in every 2,500 newborns in China — often results in misshaped or absent external ears. Although the condition rarely impairs hearing, the visible difference can be a distressing emotional burden for children as they grow up.

Twenty-two-year-old Yu, who hails from Jiangxi province and had right-ear microtia, knows how bitter it is. “I’ve saved up money for years for the operation. As I’m about to graduate, it could affect my career and marriage,” he says.

ALSO READ: 3D bone, organ models generation quicker, safer due to AI tech

“I had tried to apply for a summer job,” Yu recalls, touching the gauze wrapped around his newly sculpted ear. “But, they told me they would only hire people with ‘regular faces’.”

The malformation often leads parents, overwhelmed by guilt, to desperately seek treatment for their children. “As parents, we must find a way to fix his ear. Since his birth, we’ve been actively seeking out hospitals to fix it,” says a father surnamed Wang whose eight-year-old son’s right ear is afflicted by microtia.

Guo’s therapy is spread over two phases. Initially, he makes an incision on the patient’s head to insert a tissue expander under the skin that enables the skin near the outer ear to expand to accommodate the ear framework. This allows the patient to carry the expander, which looks like a swelling on the head, for three to four months.

The challenge comes in the second stage when he removes the expander, leaving a pocket in the outer ear area, while aides help to extract cartilages from the patient’s ribs.

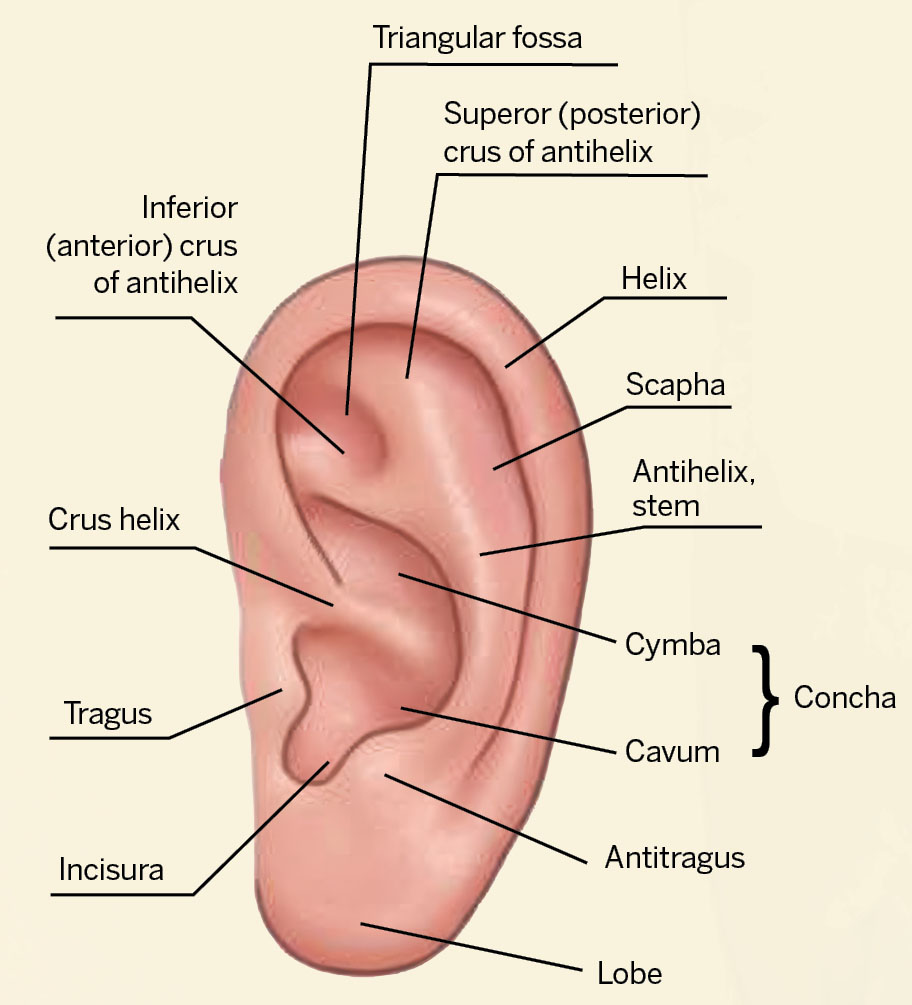

Due to the varying degrees of firmness and the shape of cartilages, Guo needs to decide on the ear’s design on the spot and this requires a combination of refined surgical skills and aesthetic mastery. “The ear is one of the most complex organs in the human body in terms of shape,” he explains. “It demands careful observation and a deep understanding of the material.”

After an hour of delicate surgery, Guo plants the ear framework under the expanded skin on the patient’s head and sutures the incision. A device will pump out the air in the pocket to make the “ear” appear. A few more days are required for observation before the patient can be discharged and return to daily life with new “ears”.

Guo received his bachelor’s degree in clinical medicine from the Fourth Military Medical University in Xi’an, Shaanxi province, in 1983. Specializing in plastic surgery, he had performed a string of operations involving ears, noses, fingers and breasts. His career had taken him from Xi’an to Beijing, back to Xi’an, and to Shenzhen in 2023 after acquiring study and exchange experiences in the United States in the 1990s.

He successfully led the completion of Asia’s first, and the world’s second face transplantation surgery in 2006, restoring the right eyes, lips and parts of the left face of a man who had been attacked by a bear. The breakthrough won him first prize in the State Scientific and Technological Progress Awards. In 2017, Guo and his colleagues transplanted a regenerated ear, constructed from rib cartilage and grown under expanded skin on a patient’s arm, onto his head. In recent years, he has focused more on reconstructing ears, having completed some 500 surgeries annually.

To Guo, creating a lifelike ear framework is enormously satisfying for both patients and himself. He has spent decades improving his ear-carving skills, not only at medical schools, but also, incredibly enough, in street markets.

Inspiring future

He started practicing with vegetables — potatoes, carrots and even large mustard greens — whose texture Guo believes resembles cartilage. “At first, you need to construct the helix, then the scapha and triangular fossa. It’ll be followed by the most challenging parts — the tragus and antitragus,” he explains.

“Later, I moved on to pork ribs. I would buy some ribs, remove the cartilages and use them to practice my techniques. Afterward, I could cook and eat the rest of the ribs, so nothing is wasted,” he says, adding he still asks students to do the same.

He tells China Daily his job requires an artist’s eyes. Talking about the carving study reminds Guo of his days in Xi’an. “I was quite familiar with carving instructors from the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts. When they had a sculpture lesson during which students and teachers work with clay, I would join them from time to time. While I may not regularly practice other art forms like painting, I truly appreciate and enjoy viewing such works, and often visit museums and galleries.”

At an age when most people would slow down, Guo moved to Shenzhen, leading a team at Shenzhen New Frontier United Family — a private hospital set up by a Hong Kong group. On weekdays, he holds outpatient clinics, performs surgeries and teaches young doctors. On weekends, he travels across the country, either to provide volunteer medical services or attend conferences.

As he had done before, Guo spends a lot of time with children there and would speak to them in a language they understand. “I once told a little patient we were ‘planting a small potato’ in you and let your mom water it every day. When that little potato grows into a big one, Grandpa Guo will come to take it out.”

“After surgery, we organize various sessions — communication workshops, English lessons and even Cantonese classes — creating a warm and supportive environment for children,” says Guo, adding that doctors need to understand how to heal both the body and the heart.

He’s also devoting more energy to nurturing students who can carry forward his surgical artistry. “A surgeon’s growth cycle is simply too long. It’s not like other professions. Training a skilled chef may take years, but training a doctor takes a lifetime.”

Sharing vision

Having launched a new career in Shenzhen, Guo dreams of leveraging the Greater Bay Area’s international platform to showcase the achievements made in Chinese plastic surgery. “Building a world-class center for ear reconstruction … and that’s why I came to Shenzhen — a true gateway to the world.”

Compared with the techniques used by his foreign counterparts, Guo says he has streamlined some procedures, reducing the overall surgical cycle to three to four months, and allowing patients to change the water in the expanders at home by themselves through new devices, all setting new benchmarks for the procedure.

“Early in my career, I dreamed of joining the world’s top medical centers, places like those in Australia and the United States where the patients come from across the globe,” says Guo. “Now that China has made significant progress in medicine, just as it does with smartphones and drones, we’re ready to serve patients from around the world.”

Guo’s confidence derives from reality. His patients include expatriates working in Shenzhen, as well as from the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Mongolia and Latin America.

In his view, Shenzhen and Hong Kong form great synergy in healthcare development.

“The Chinese mainland has a large population and, as a result, its doctors have extensive clinical experience,” says Guo, who expects Shenzhen to become a clinical training hub for international doctors. “My team has sparked interest from surgeons in New Zealand, India and South America. I aim to gradually welcome more international doctors to train here.”

Shenzhen is also home to leading medical equipment manufacturers like Mindray, a fact that helps doctors get advanced medical equipment faster, he says.

Having academic exchanges in Hong Kong is also very convenient for doctors from all over the world, and the special administrative region’s global connectivity makes the city an ideal hub for luring overseas patients, he says.

With his grand vision, Guo is confident that Shenzhen’s manufacturing prowess and Hong Kong’s global links would create a brighter tomorrow for Chinese doctors.

And, there’s still much room for improvement in medical development across the Greater Bay Area. The key lies in having more medical schools and research facilities. In this regard, the advantages of Hong Kong and Shenzhen in education and research can propel the entire region’s development and progress.

“Now, I can finally have a decent photo for my identity card,” says Yu as Guo entered the patient’s ward on his regular rounds.

Guo then visited a boy named Bi who had also undergone surgery, and was resting in bed with his eyes closed. When asked what Bi most wanted to do after the operation, his mother quipped: “He wants to wear sunglasses to look cool.”

On his way back to his office, Guo paused on a corridor filled with paintings on walls drawn by hospitalized children. “They presented me with many of these paintings and other gifts before they went home, and my office is almost completely filled up,” Guo grins.

“These are the most meaningful rewards for my job. One day, I hope to open a modest little museum to preserve all these precious gifts from the children.”

Contact the writer at williamxu@chinadailyhk.com