When the Hong Kong International Literary Festival kicks off next week, the spotlight will shine gloriously on women writers of diverse backgrounds and persuasions. Amy Mullins spoke to some of them.

As in previous years, the 2024 Hong Kong International Literary Festival has gathered established and emerging writers of fiction, nonfiction and poetry for a week of talks, readings, discussions and workshops. Whether it’s tips for getting published or getting to meet one’s favorite author, the HKILF has something for everyone who is interested in books. And since the festival wraps just two days after International Women’s Day on March 8, a spotlight on women’s writing seems most germane to a celebration of the written word.

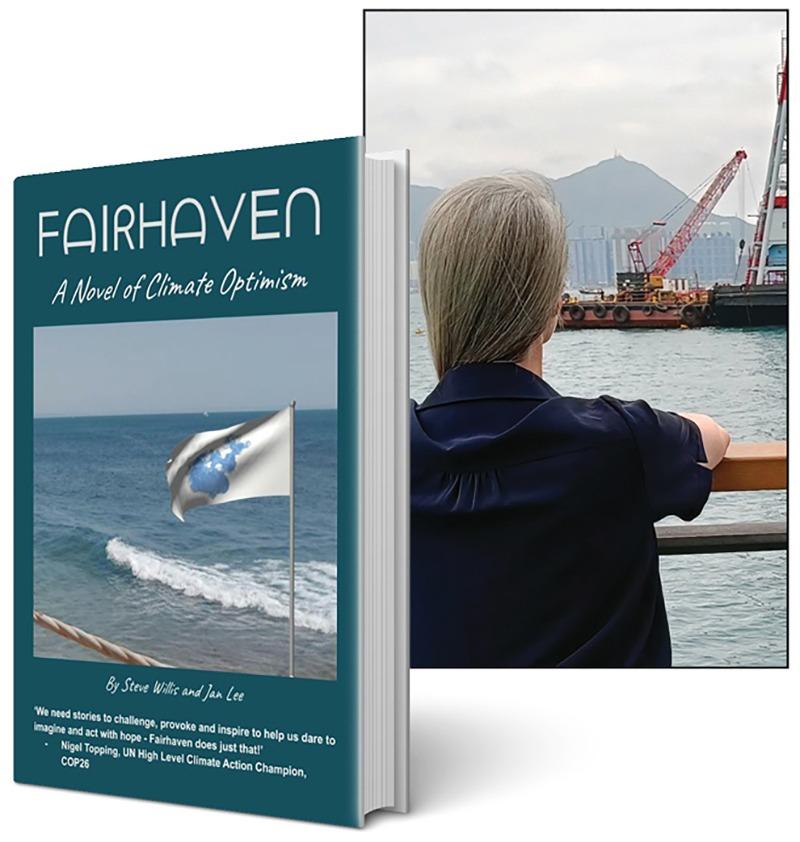

At a time when women’s rights and freedoms are under threat around the globe, many still question the relevance of IWD. However, listening to other voices is always relevant. Hong Kong climate-fiction author Jan Lee, featured in HKILF 2024, puts it succinctly when asked how she feels about the woman-writer label: “Are male writers asked about ‘writing as a man’?”

The answer, of course, is no.

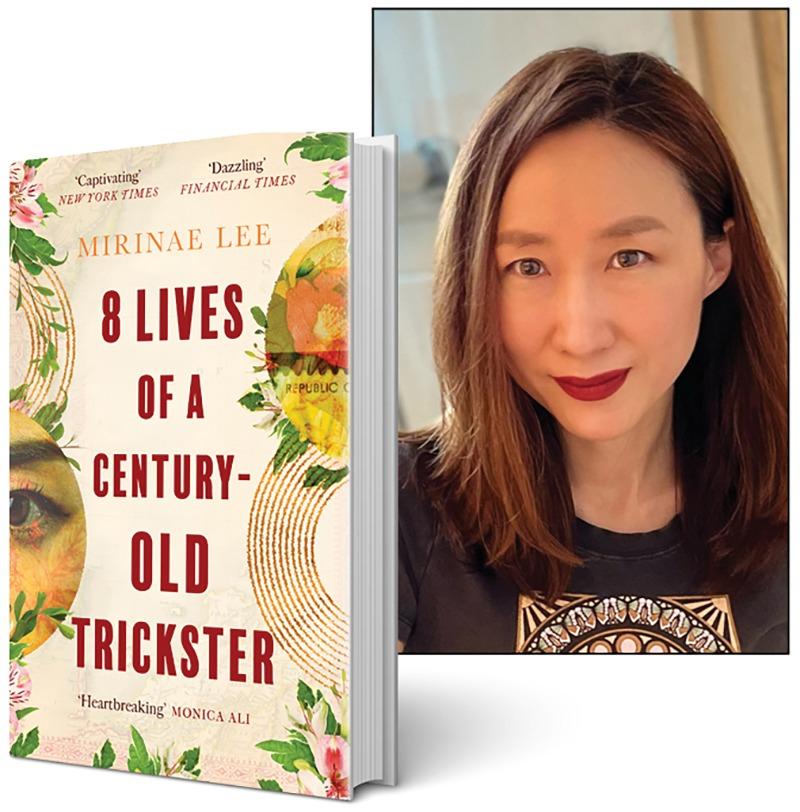

Republic of Korea writer Mirinae Lee’s 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster follows a pattern of women forced into sexual slavery across different cultures at the time of war. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Republic of Korea writer Mirinae Lee’s 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster follows a pattern of women forced into sexual slavery across different cultures at the time of war. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Vietnamese writer Nguyên Phan Qué Mai recalls being taken to task by a male author from her country for writing about something she had no experience of. “Why do you dare write about the war? You were not there. You were not a soldier,” Nguyên was told.

“Those words are reflective of the fact that many people still don’t take women’s writing seriously, as if we are only capable of writing about domestic issues,” Nguyên says. “I love being a woman, but when I write, I need to be more than that. I need to become a man, a child, a grandmother, a grandfather. I am an artist, a builder of imaginary worlds when I write. So it would be nice for such a label as ‘woman writer’ to be removed and all authors treated equally.”

READ MORE: Writer delivers cold, hard fiction

Hong Kong-based Republic of Korea author Mirinae Lee echoes Nguyên’s sentiments. She recalls that in 1997, Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling had un-gendered her name because “boys wouldn’t want to read a fantasy novel written by a female author”. While greater inclusivity is in evidence nowadays, “I still see that many of my male acquaintances are often reluctant to read novels with female protagonists written by female authors.”

Fortunately though, the reverse is not true.

Jan Lee, who co-wrote Fairhaven — A Novel of Climate Optimism, with Steve Willis, bucked the trend by painting a world changed for the better. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Jan Lee, who co-wrote Fairhaven — A Novel of Climate Optimism, with Steve Willis, bucked the trend by painting a world changed for the better. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Feminist forays

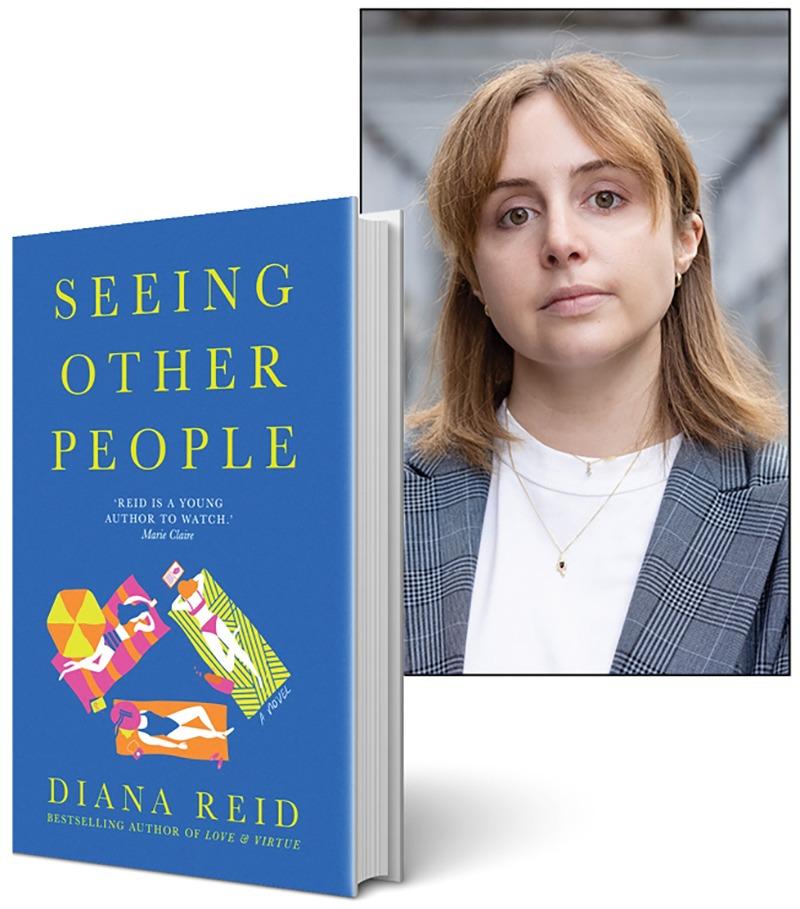

The HKILF has a raft of talks and readings that make space for women’s perspectives, the sessions titled “Imprint 22: Women’s Voices”, hosted by the Women in Publishing Society (March 7), and “The Stories Women Journalists Tell” with Zela Chin, Jervina Lao and Caitlin Liu (March 10), for example. Diana Reid, who won the prestigious MUD Literary Prize, awarded annually at the Adelaide Writers’ Week, appears on March 6 and 7 to talk about her novels Love and Virtue and Seeing Other People. Reid’s novels are incredibly vivid, current, feminist explorations of sex, power, love, class, and relationships. Seeing Other People deconstructs sisters Charlie and Eleanor’s sometimes caustic, sometimes envious, always-complex relationship over a summer that pushes it to its limits.

Mirinae Lee and Nguyên will reach back to explore the complicated legacies of war and colonialism in their books 8 Lives of a Century-old Trickster (March 9) and Dust Child (March 8). Mirinae Lee’s genre-defying debut follows the lifelong struggle of a woman from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to survive abuse by manipulating her identity at the risk of losing it altogether. Nguyên similarly tackles identity from the perspective of ordinary people trying to get out from under the impact of generational trauma. Both reflect on defining moments in history that, until recently, have been interpreted by men.

For Mirinae Lee, the female struggle interrogated in 8 Lives is more universal than conventional wisdom holds. The book follows a pattern of sex slavery from World War II, to Korea, to Vietnam, showing that Japanese, Korean and American soldiers were equally culpable. “This kind of tragic history of women in wartime tends to repeat itself whether it’s in the West or the East,” she says.

Nguyên for her part looks beyond her wartime setting to celebrate Vietnam’s 4,000-year-old cultural history. “So many books have been written from the viewpoints of men about this time,” says the writer, who “wanted to insert voices from Vietnamese women” into the narrative for a change. She has based her protagonists, the sisters Trang and Quýnh, “on those who can contradict the white male’s gaze on Vietnamese women and show that we are not pitiful, naive or opportunistic as depicted in many Hollywood movies about Vietnam; rather, we are often the pillars of our families and the Vietnamese society”. On top of that, Nguyên shines a light in her novel on the nearly 100,000 mixed-race children born during the American war in Vietnam, many of them still seeking an identity.

The layered and complicated relationship between two sisters gets deconstructed by Australian writer Diana Reid in Seeing Other People. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The layered and complicated relationship between two sisters gets deconstructed by Australian writer Diana Reid in Seeing Other People. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Fantastic output

Women writing genre fiction often end up being doubly marginalized. However, such attitudes are changing, says writer of young-adult fiction Jordan Rivet, known for the fantasy series Empire of Talents and The Lost Clone sci-fi trilogy. She will be leading a workshop for writers aged 13 and above on world-building, which is the backbone of sci-fi and fantasy (March 9).

Rivet’s sci-fi saga follows Jane, an abandoned clone on a mission to uncover her origins, first as a surrogate best mate for a rich kid and finally as a murder target.

Co-authored by Steve Willis and Jan Lee, Fairhaven — A Novel of Climate Optimism follows Malaysia-born Grace Chan, a veteran of climate-change impact, as she combats our common environmental dilemma. The book’s hopeful ending makes it something of an outlier. “It is possible to be optimistic that things will change for the better, even about topics that currently appear dire, like today’s climate crisis,” says Jan Lee, who draws inspiration from sci-fi great Ursula K. Le Guin, who once said, “The exercise of imagination has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent.”

“In the book, we pose the question: Do you want a Mad-Max future or do you want a Fairhaven future? And we show what a Fairhaven future looks like,” Jan Lee says.

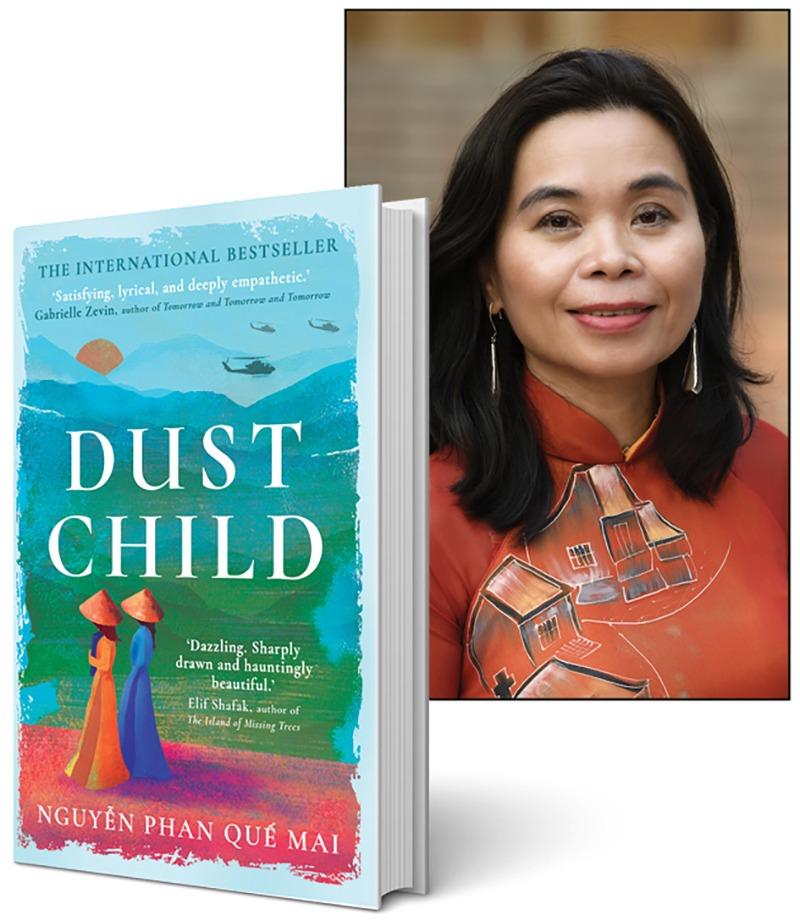

In Dust Child, Vietnamese writer Nguyên Phan Qué Mai goes beyond the book’s wartime setting to celebrate her country’s rich and diverse cultural history. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In Dust Child, Vietnamese writer Nguyên Phan Qué Mai goes beyond the book’s wartime setting to celebrate her country’s rich and diverse cultural history. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Many readers hold the view that genre fiction is a vital literary form, offering a better microscope on the present than the fiction of social realism. Le Guin, Octavia Butler and Connie Willis are, rightfully, legends in the field of sci-fi. Over the last decade, the trend has been to achieve greater gender balance among the winners of major sci-fi and speculative fiction awards, like the Hugo, and, increasingly, fantasy best-sellers are being authored by women.

Mirinae Lee doesn’t see sci-fi in opposition to literary fiction, citing George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale as examples of literature that “explores the vicissitudes of human nature under extreme sociopolitical situations”.

ALSO READ: Can we beat the bots?

Rivet agrees. “Speculative fiction can be a more playful space than genres rooted in the real world. You can use a futuristic or fantastical world to explore ideas, sometimes pushing them to an extreme that wouldn’t be possible in reality. Fiction involves magnifying specific aspects of the world in order to explore their possibilities. In speculative fiction, your magnifying glass is limitless.”

Until books are indeed judged by their covers and we collectively think beyond borders, the HKILF and events like it will have to continue carving out niches for airing alternative views. “I dream about a world where literature is inclusive and celebrates diversity, where the writings of Asian, Black, LGBTQ and indigenous authors are mainstreamed and stand proudly, shoulder-to-shoulder, with other authors, where we don’t need to belong to a specific category,” says Nguyên.

As far as labels go, Jan Lee has this to say: “I’ll support whatever booksellers do to get people to read more books!”

If you go

Hong Kong International Literary Festival

Dates: March 4-10

Venue: Various venues