In the final installment of her series on Hong Kong’s women artists, Chitralekha Basu finds out about the ones to watch out for and how they are adapting their practices to a global artistic landscape with HK characteristics.

Scan the marquee international art events this year. If you find a Hong Kong presence, in all likelihood the artist is a woman.

Tobias Berger, curatorial director of Serakai Studio, and one of Hong Kong’s preeminent curators, says, “Look at this year’s Shanghai Biennale. There was one Hong Kong artist, and it was Jaffa Lam (1973-). Look at the Seoul Mediacity Biennale. The only Hong Kong artists there were Angela Su (1958-) and So Wing-po (1985-). Look at the big international galleries showing Hong Kong artists overseas. White Cube is planning a huge show with Firenze Lai (1984-) in Mason’s Yard, London, one of the most important art spaces in the city.

“These artists obviously have the quality because overseas curators don’t care if they are from Hong Kong or if they’re male or female. They just want good art.”

READ MORE: The insiders’ views

Berger goes on to add that the point of championing the cause of women artists — as indeed he had done several times over by commissioning mega-scale solo shows to women artists during his time as head of art at Tai Kwun, in the late 2010s — was to initiate the gradual obsolescence of those spaces reserved for them then.

“Looking back, I think that worked,” Berger says. He goes on to add that if today a Hong Kong facility for showing contemporary art were to “put on a show with 10 female artists from China, I would have a problem with that, or let’s say I wouldn’t do that because I think that time is over”.

Think global, make local

It isn’t just the Hong Kong curators who have broadened their horizons to celebrate what lies beyond “the simplistic lens of gender”, as Chris Wan Feng, head of Gallery and Exhibitions at Asia Society Hong Kong Center, calls it. Today, a number of the city’s women artists are equally indifferent to the idea of a gender-oriented framing when they present their work to the world. Many of them do not feel obliged to represent the female worldview, or feminine sensibilities, through their work though sometimes that could happen organically. Man Fung-yi (1968-), widely known for her metallic-thread sculptures of cheongsams that have been exhibited in prestigious venues around the world, says that she has never “needed to figure out femininity in my artwork for it’s in my blood”.

ALSO READ: Drawing attention

Similarly, many Hong Kong women artists no longer see themselves as purveyors of the Hong Kong experience. “Artists today are working in languages that are not necessarily regionally grounded,” says Tina Pang, curator of Hong Kong Visual Culture at M+. “They are working within a global artistic landscape … with an eye on what is happening globally and making work that they hope can be relevant and speak to a wider audience.”

And yet, to rework a popular adage, you can take the artist out of the city but, often enough, not the city out of the artist. Chan Ka-kiu (1995-) started out as a maker of quirky — and also tenderly empathetic on a certain level — videos about love hotels in Mong Kok and “a lonely girl in Central, who sought to satisfy her need for intimacy by getting a massage”, which was on show at Art Basel Hong Kong 2019. She also created a wistfully poignant performance piece to accompany the video installations, based on her experience of watching middle-aged women handing out flyers in Central, “a social interaction that no longer exists”.

Chan adds that while she did not set out “to include or highlight Hong Kong” in her works, “it is only in retrospect that I realize that they had represented a sort of social landscape” of the city.

ALSO READ: Making it count

There are no apparent Hong Kong-specific cultural references in either her ongoing solo show, Cosmic Dust: Ephemeral Redamancy, at De Sarthe’s gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, or her pieces in the currently running Hart Haus-hosted group show, Madam I’m Adam. Chan says that the video installation in the latter show “revolves around themes of space, cyclicality, and reincarnation” and was “inspired by certain anxieties or discomforts that stem from where we are situated in society, especially after COVID-19 as well as the sudden surge of artificial intelligence”.

Cantonese remains the preferred language of the Toronto-born artist for her video works. “Cantonese is my native language after all, and there is a certain humor in my work that I can only express in Cantonese.”

New lens on familiar icons

Hong Kong’s over-familiar skyline continues to spur artists into finding newer forms and mediums of representing it. Nina Pryde (1945-) does this by combining ink sketches, photos and collage. Angela Yuen (1991-) creates compelling visual narratives around silhouettes of Hong Kong landmarks fashioned out of scraps of fabric and vintage plastic toys in her kinetic sculptures. Sophie Cheung (1983-) uses the humble nylon eraser, and its shavings, to construct images of the chrome-and-glass facades of the city’s ubiquitous high-rises.

Henrietta Tsui-Leung, founder of Ora-Ora gallery, which represents both Pryde and Cheung, says that while the former “incorporates surprising details from modern life in Hong Kong through her innovative use of collage”, Cheung’s uniqueness is in her use of “ink from Hong Kong newspapers”.

“Both artists are evocative of a time and place and inspire a form of nostalgia,” says Tsui-Leung, underscoring the fact that both Pryde and Cheung have adapted the tradition of Chinese ink to serve their own distinct visual language.

Another Hong Kong cultural cliche — the city’s rainbow-colored neon heritage — continues to lend itself to newer artistic forms and expressions as well. Hong Kong-born, Paris-based artist Chankalun (1988-) makes stunning large-scale installations — Light as Air, installed in the Tai Kwun courtyard to mark Art Basel Hong Kong 2023, for example — as well as quaint minimalist sculptures meant to encourage body positivity.

Sharmaine Kwan (1996-), who has a number of large-scale neon-art installations commissioned by the likes of the Hong Kong Development Bureau and Henderson Land under her belt, makes hybrid work such as neon-design-based-or-inspired 2D artworks, sculptures, immersive digital environments and nonfungible tokens.

ALSO READ: Catalysts of change

“Artists like Kwan demonstrate digital art’s potential for substance,” says Heiman Ng, founder and director of Art Prince Advisory. “Her international exhibitions, from Shanghai to Moscow — the latter displayed on an enormous digital cuboid near the Kremlin — demonstrate how digital media can amplify a profound artistic vision and narrate compelling stories from Hong Kong.”

“The digital medium is merely one channel among many through which they choose to communicate,” Ng says of the late-millennial and Gen-Z Hong Kong artists like Kwan, writer-illustrator Sophia Hotung (1994-), and Mizuki Nishiyama (1998-), who mixes soil extracted from her ancestral land in Japan into her oil paintings and patchwork tapestries as a nod to a ritual tied to her ethnicity.

Like Nishiyama, who has Hong Kong, Japanese and Italian heritage, many Hong Kong artists of this generation have been exposed to multiple cultures. As young artists living and working in inclusive, multicultural Hong Kong — ahead of many other places in the technology innovation curve — these digital natives are naturally drawn to creative platforms on the digital realm and making hybrid works that exist in both physical, digital and Web3 versions, even as many of them still rely on the oldest forms and media of making art.

Of high tech and empathy

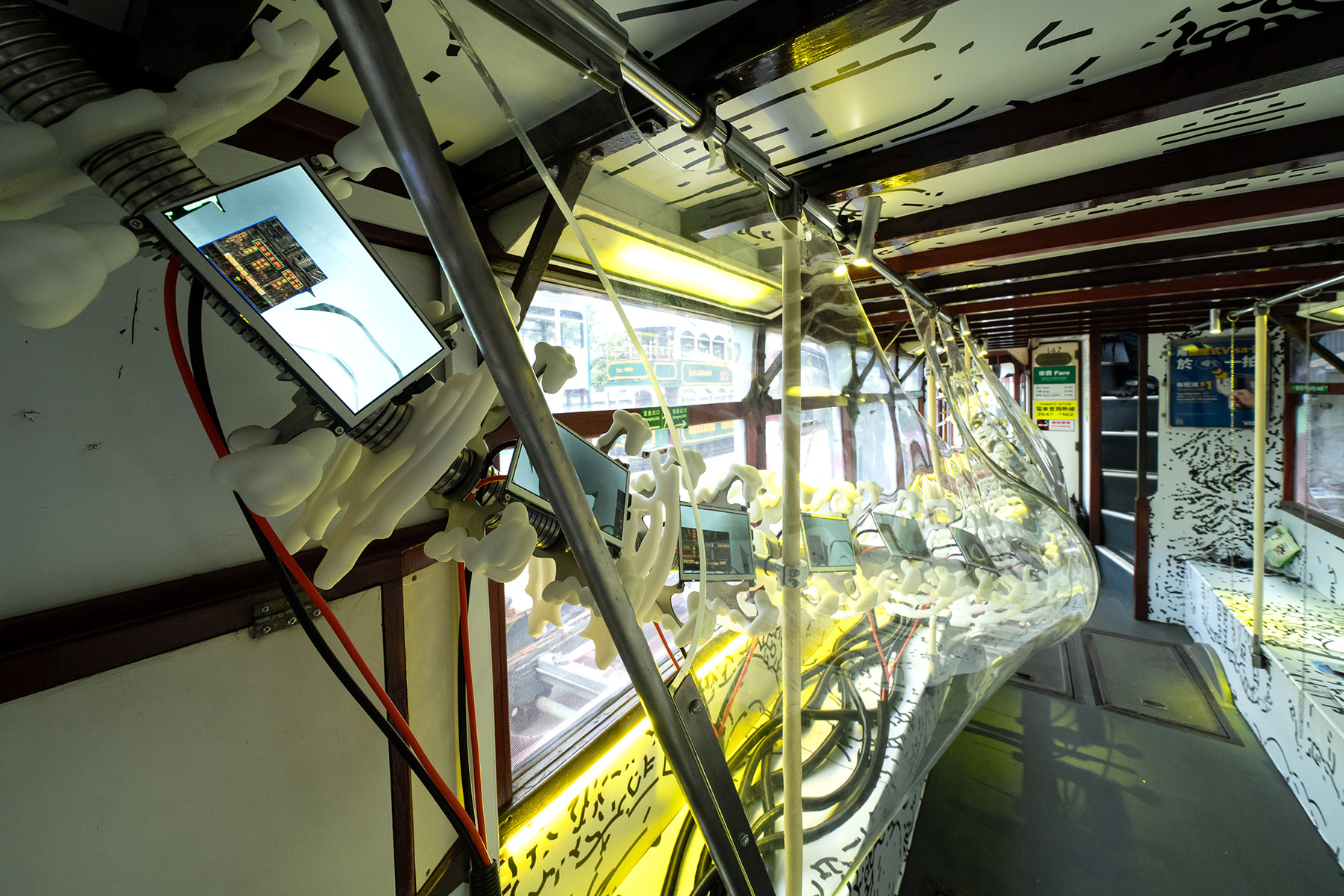

Pat Wong Wing-shan’s (1990-) drawings of life inside a Hong Kong tram depot are a significant component of Ding Lab, a Hong Kong Arts Development Council-sponsored arts-tech exhibition held in November. Together with fellow Hong Kong Baptist University academic Kachi Chan, Wong created a multilayered tech-driven immersive experience that unfolds over a tram ride. Based on field research and a community-engaged practice that involved interacting closely with workers of the Hong Kong Tramways, the duo designed a speculative narrative. The story is told through field notes, a four-channel video, playing on an unevenly cut LED screen, a fiberglass sculpture “resembling a sea wave that has been stranded on the shore” on the Belcher Bay Promenade, and a mammoth installation resembling the spine of a prehistoric reptilian beast, winding its way across the tram’s lower deck. The 16 digital screens placed in the groove of each vertebrae live stream the footage of street scenes captured by a camera on the moving vehicle.

“As the images appear, gaps gradually emerge — visualized as checkerboard-like voids beneath each frame,” says Wong. “The memory system attempts to fill these gaps by drawing on an image archive stored on a hard drive hidden at the back of the tram — footage recorded from the same tram route in the past. The system patches the missing pieces according to the original spatial layout, yet the replacement images are inevitably mismatched and displaced. Through this deliberate error, we wanted to reveal how humans cope with memory loss: We confuse, rearrange, and reconstruct fragments of the past, often replacing what we have forgotten with idealized or distorted recollections.”

Her sensitive, though unsentimental, drawings of intense clutter strewn around partially dismantled tram cars in the workshop reveal a different, perhaps more human, side to a tech-heavy project. The images of haphazardly stacked files, sheaves of paper accumulating on the floor, at the foot of a vintage metallic stand fan, and cast-off staff-uniform shirts, draped around the back of molded plastic chairs, serve as astutely observed documentation of a way of life that despite its existence in the present belongs in another time.

Oddly enough, Wong still has to deal with “the outdated stereotype that women do not seriously engage with digital tools or technology”. Hence part of her remit as an artist-academic is to “keep critical conversations alive, continually reinterpret the discipline, and explore how it can evolve and transform in ways that resonate with a wider public”.

Women contribute “empathy, intuition, and emotional depth” to digital art, says Anita Lam, co-founder of the creative technology platform The Collective HK. “In this way, technology becomes a powerful new language — a canvas through which women can turn sensitivity and imagination into immersive experiences that engage audiences in fresh and meaningful ways.”