Dating back thousands of years, traditional Chinese calligraphy continues to fascinate present-day makers, serving as material for new-media and moving-image artists. Leon Lee reports on three Hong Kong artists who have made calligraphy an integral part of their practice.

In ancient China, the art of calligraphy was regarded as the highest form of artistic expression. Today, a number of contemporary Hong Kong artists are reimagining the art form. By mixing classic Chinese lettering with new techniques and avant-garde technologies, they are expanding the possibilities of calligraphy, and catering to a broader audience.

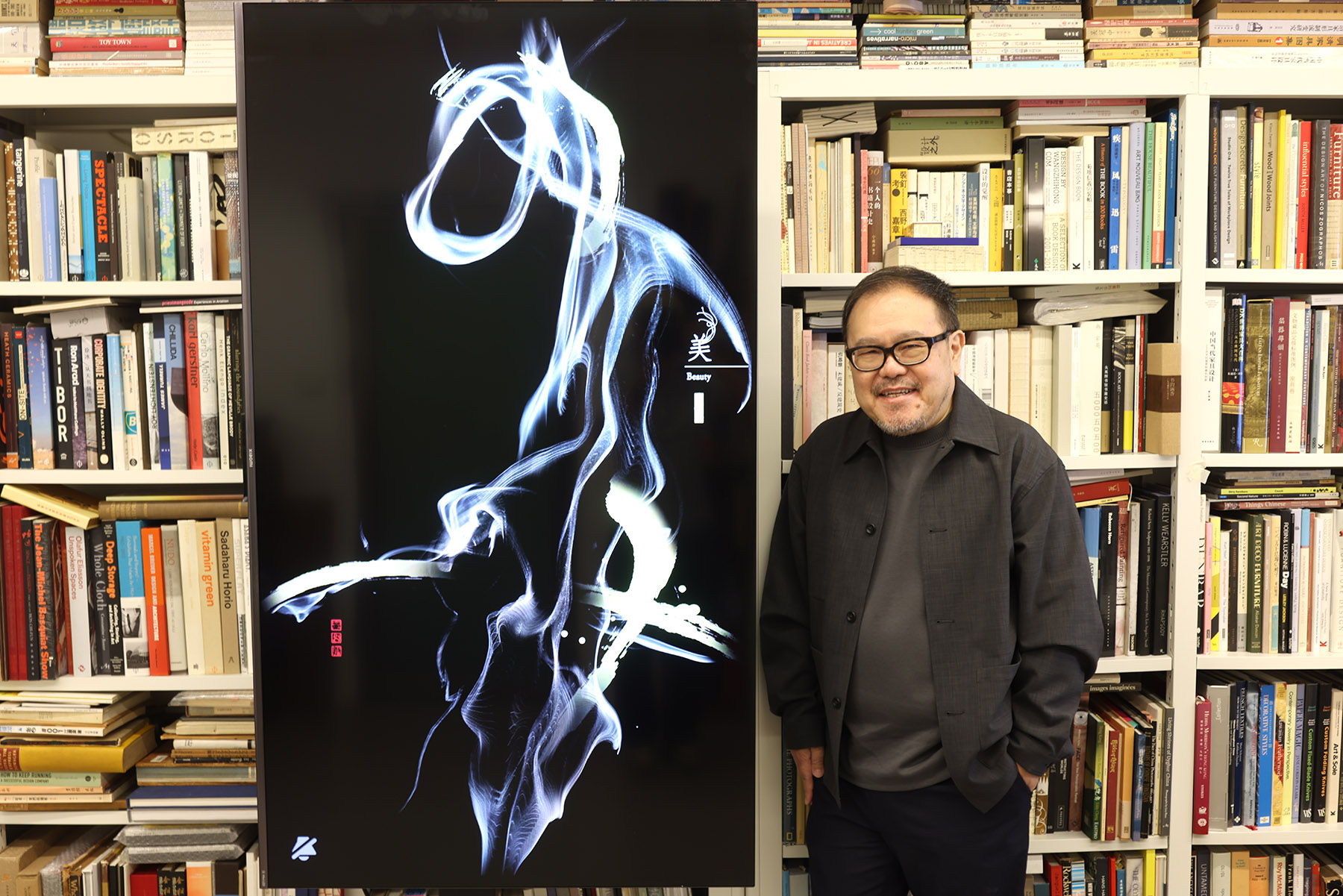

Holy smoke

For artists who grew up in Hong Kong, their first brush with Chinese calligraphy happened in primary school. Artist and designer Freeman Lau remembers taking a shine to practicing calligraphy as a boy, loving what several of his classmates saw as routine schoolwork.

READ MORE: Inaugural Hong Kong AI Art Festival opens: Will AI replace artists?

“Ever since I was little, I’ve always enjoyed holding a brush. When local designers began using calligraphy characters in their creations in the 1980s, those designs caught my eye. I realized just how beautiful those brushstrokes could be,” says Lau.

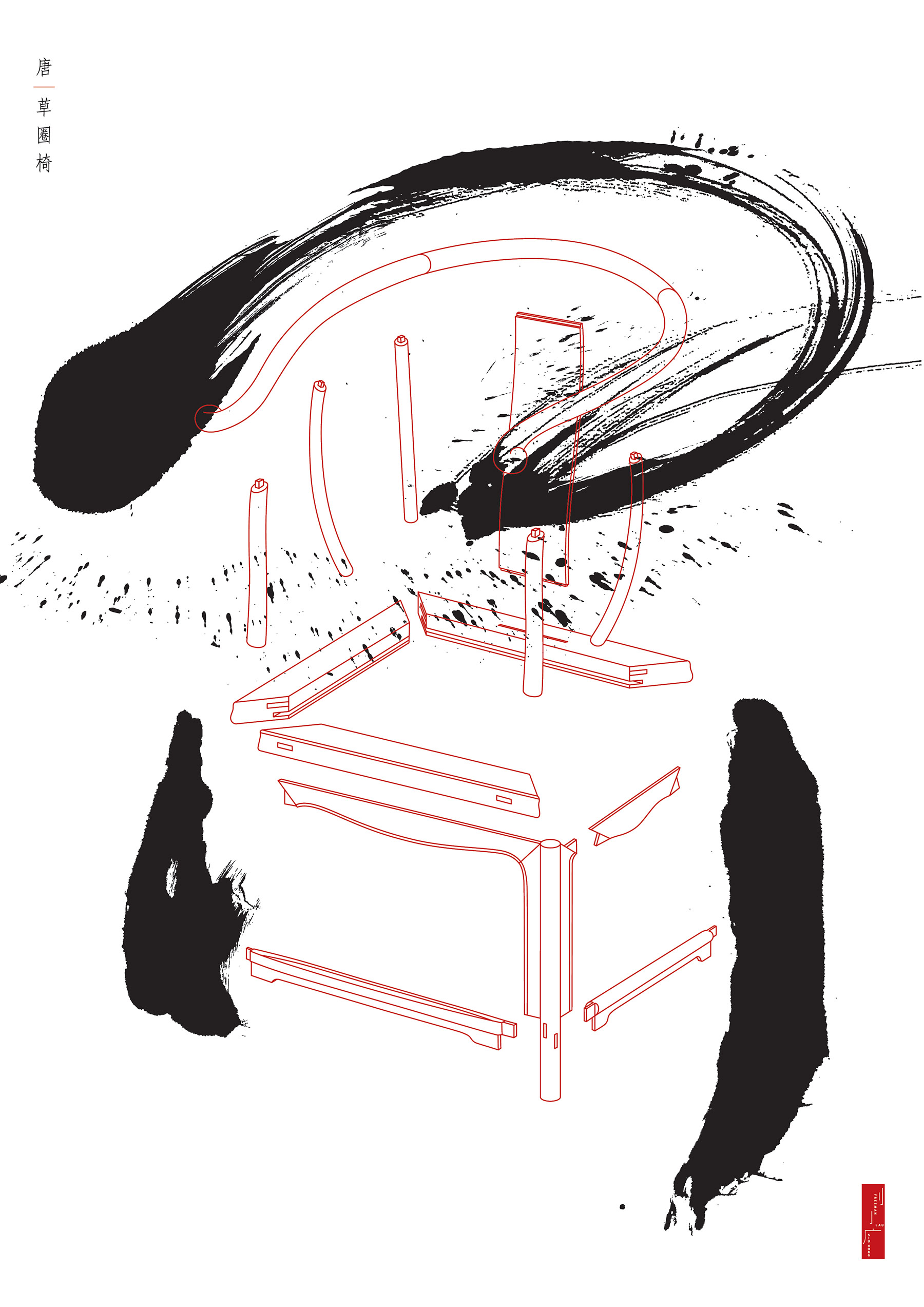

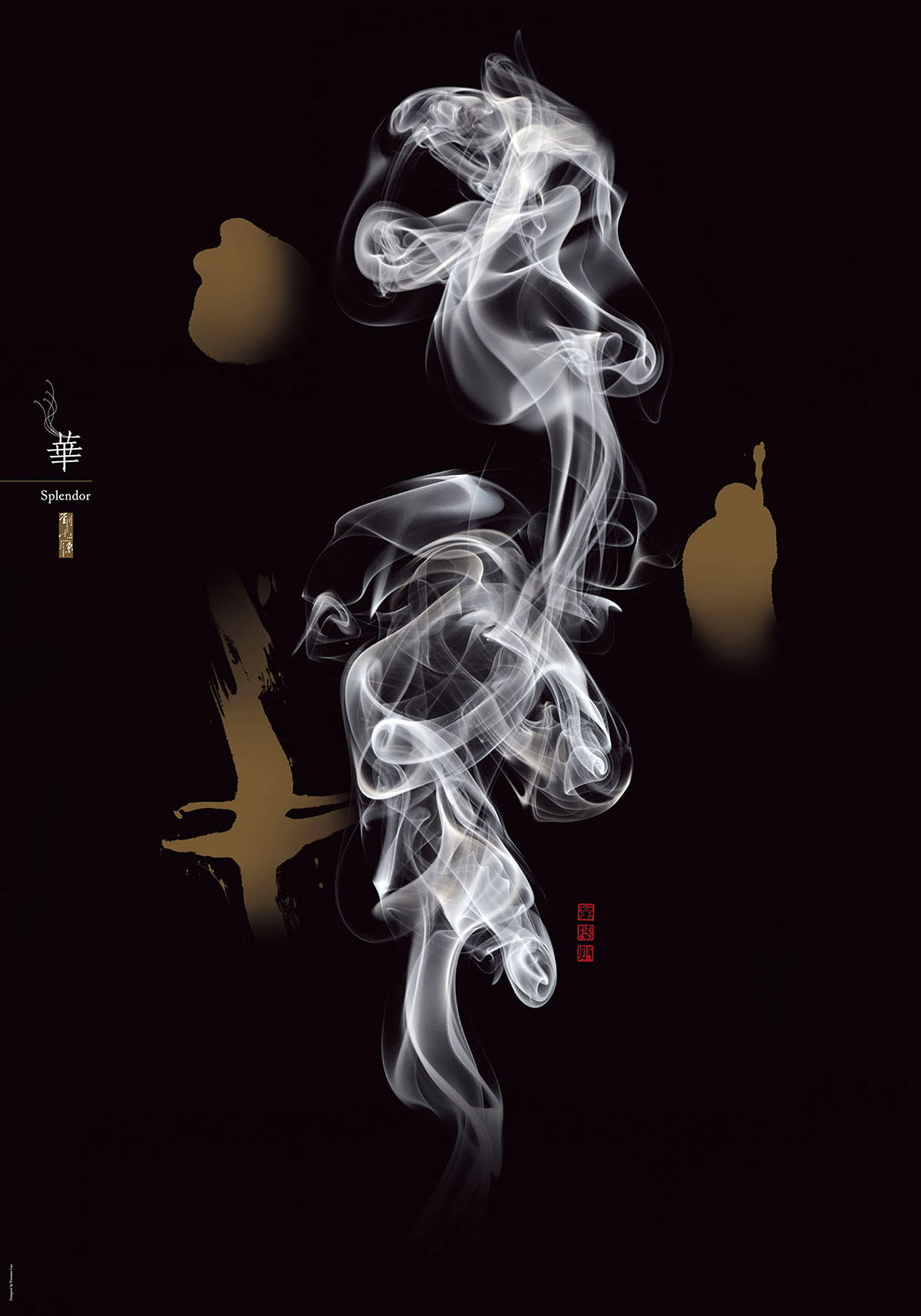

Later, in 2011, his fascination with calligraphy led to Fancy of Ink — a set of six posters showing smoke rising from a burning incense stick, creating forms that bring to mind the iconic works by master calligrapher Tong Yang-tze (1942-).

“If you burn an incense stick in a dark and quiet room, the smoke that rises up can be very beautiful. Its flowing movements reminded me of a master calligrapher moving the brush with elegance,” says Lau, explaining the inspiration behind the genesis of the posters.

For his next exhibition, By the People: Creative Chinese Characters, at the Hong Kong Museum of Art in 2022, Lau worked with an award-winning special-effects artist to make six three-minute videos based on his 2011 posters. This time, viewers could watch the rising smoke in motion, as if it were forming a Chinese character — its movement modeled after Tong’s style of mark making — before gently fading away.

Making anew

For a long time, new-media artist Chris Cheung, also known as “h0nh1m”, has been interested in the evolution, and disappearance, of ancient Chinese calligraphic styles. He uses cutting-edge technologies and a futuristic imagination to create a diverse range of calligraphy-based installations.

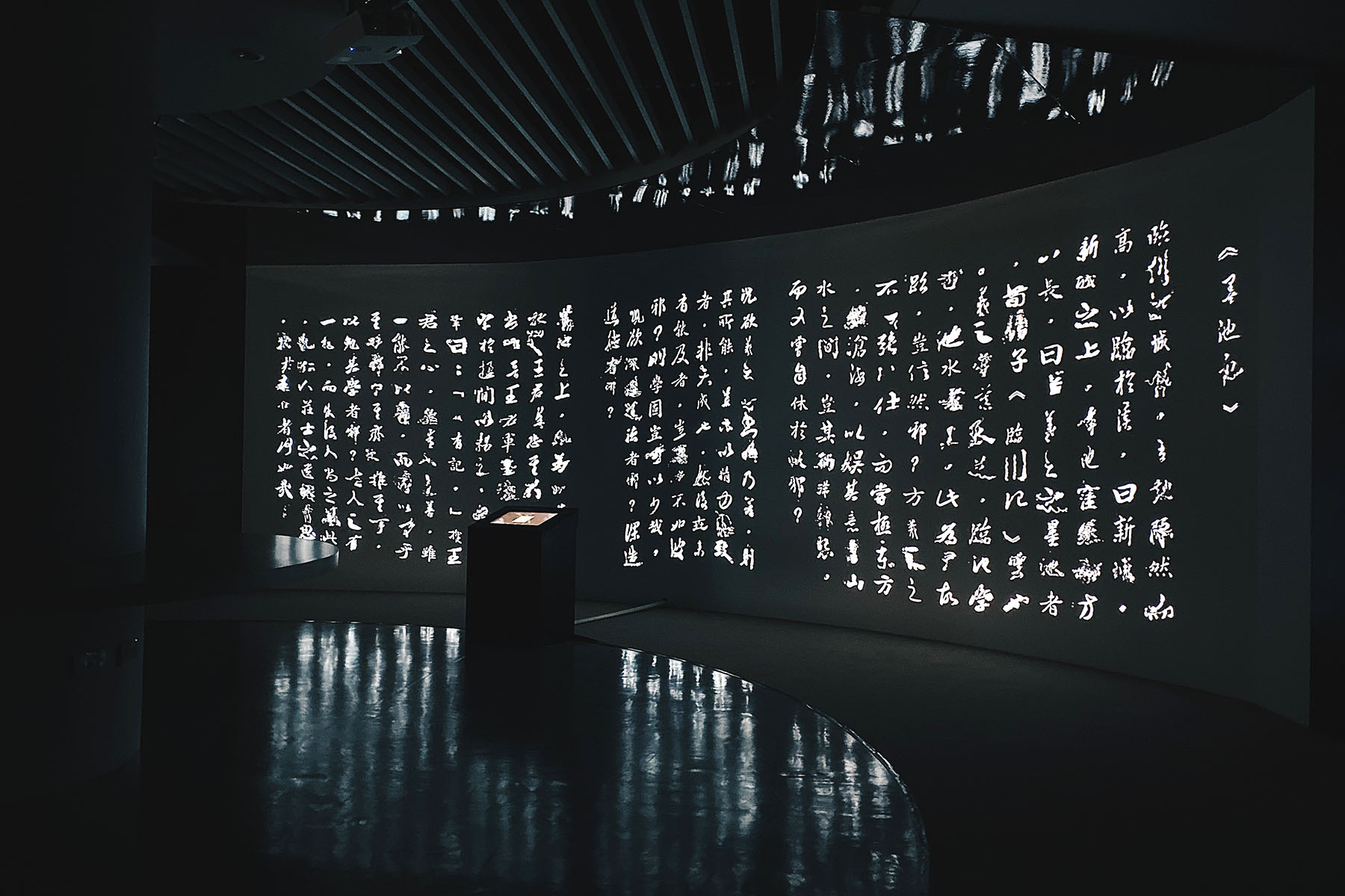

Cheung’s 2017 work, No Longer Write – Mochiji, is an interactive installation in which artificial intelligence and machine learning are used to generate Chinese calligraphy. The piece is inspired by an apocryphal story about Jin Dynasty (265-420) calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303-361), who dipped his brush into a pond so frequently that its water turned completely black.

No Longer Write – Mochiji offers an immersive experience. Chinese characters written by exhibition visitors on a touch screen are added to an ever-growing mass of calligraphy displayed on a giant screen, eventually resembling a dark pond, appearing to ripple across a number of screens.

For his 2023 piece titled Ink | Pulse, displayed on the M+ facade, the artist created an algorithm-driven generative art piece, based on master calligrapher Tong’s practice. By highlighting selected brushstrokes from 100 works in Tong’s Silent Music series, Cheung developed an algorithmic program that uses cellular automation to animate Tong’s brushstrokes — the movements reminiscent of cell division and blood circulation.

“Ink | Pulse has helped deliver the message that calligraphy is not dead,” says Cheung. He points out that with the help of digital and new-media technologies, a “traditional calligraphy piece can have a life beyond its original version”, adding, “It’s great to be able to show that we can breathe new life into something like calligraphy, and make it live.”

In 2022, Cheung created Waving Script for the Hong Kong Palace Museum. It’s a kinetic installation that uses recorded brainwave data and is programmed to replicate Cheung’s movements of copying text from an ancient piece of literature. A robotic arm fitted with a ribbon fleetingly traces the movement of brush-writing a character. A newer iteration of Waving Script is part of Cheung’s upcoming exhibition in March at the FutureScope art dome — a dedicated facility for hosting immersive cross-disciplinary art-tech experiences in Kai Tak Sports Park.

Emotional quotient

Hung Keung, a digital media artist and professor at the Cultural and Creative Arts Department of the Education University of Hong Kong, says that the idea of yi, which translates as “one” in English and which a dictionary of traditional Chinese characters defines as the line separating heaven and earth, spurs on his creative imagination.

The idea informs his digital video and interactive installation series, Dao Gives Birth to One, begun in 2008. Playing across multiple screens, the video opens with the character of yi appearing against a white background, its texture similar to the kind of paper used in Chinese calligraphy and painting. Responding to input from viewers, the piece generates the Chinese character for “two”, followed by “three”. Eventually, 10,000 Chinese characters fill the screens.

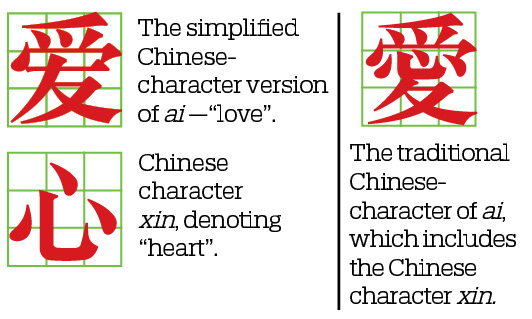

In 2018, Hung created a mechanical art installation titled Control Freak, to accompany a retrospective exhibition on the American pop-art exponent Robert Indiana (1928-2018) at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center. Best known for his iconic “LOVE” sculptures, Indiana had realized the idea in various languages, including Chinese. However, in doing so, he had opted for the simplified Chinese-character version of ai as opposed to the traditional version, which includes the Chinese character xin, denoting “heart”. Hung wanted to create a work that would “restore” the missing element.

Control Freak includes a robotic contraption fitted with magnets. One of these is embedded in an ink brush and another inside a robotic arm hidden beneath the platform. Visitors invited to write down their own versions of the “heart” character using the brush had to deal with a hidden robotic arm that traced the strokes for the character, subtly pushing the human writer to follow its lead.

“Calligraphy can bring a person’s emotion to the surface. Normally, when you write the word ‘love’, it is a tender experience. But when you are doing that with Control Freak, you are also resisting being led by it and that affects the character you will write in the end,” Hung says.

Evolution is key

While all three artists remain fascinated by both the process and the results of the art of traditional Chinese calligraphy, none considers himself a calligrapher. Lau says that his calligraphy skills do not meet the high standards required to make traditional calligraphy. But then, he adds, coming up short is perhaps natural, seeing that the craft was invented thousands of years ago, and the fact that writing is no longer our primary means of communicating with words.

Hung adds that in the present context rather than authenticity of form, it is perhaps more important to consider whether a piece of calligraphy, or calligraphy-based art or design, can make an impact on viewers. “The more people engage with calligraphy, the more visible its nuances are.”

He also recommends that calligraphy pundits adopt a more flexible approach toward newer interpretations of a piece of traditional calligraphy. It is only by letting an art form evolve that newer generations of artists can remain sufficiently interested to want to experiment with it.