A naive charm is the hallmark of the mysterious artworks by Gaylord Chan — an iconic painter and a champion of contemporary art during its early days in Hong Kong. An ongoing show at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center throws light on Chan’s long and multifaceted career. Mariella Radaelli reports.

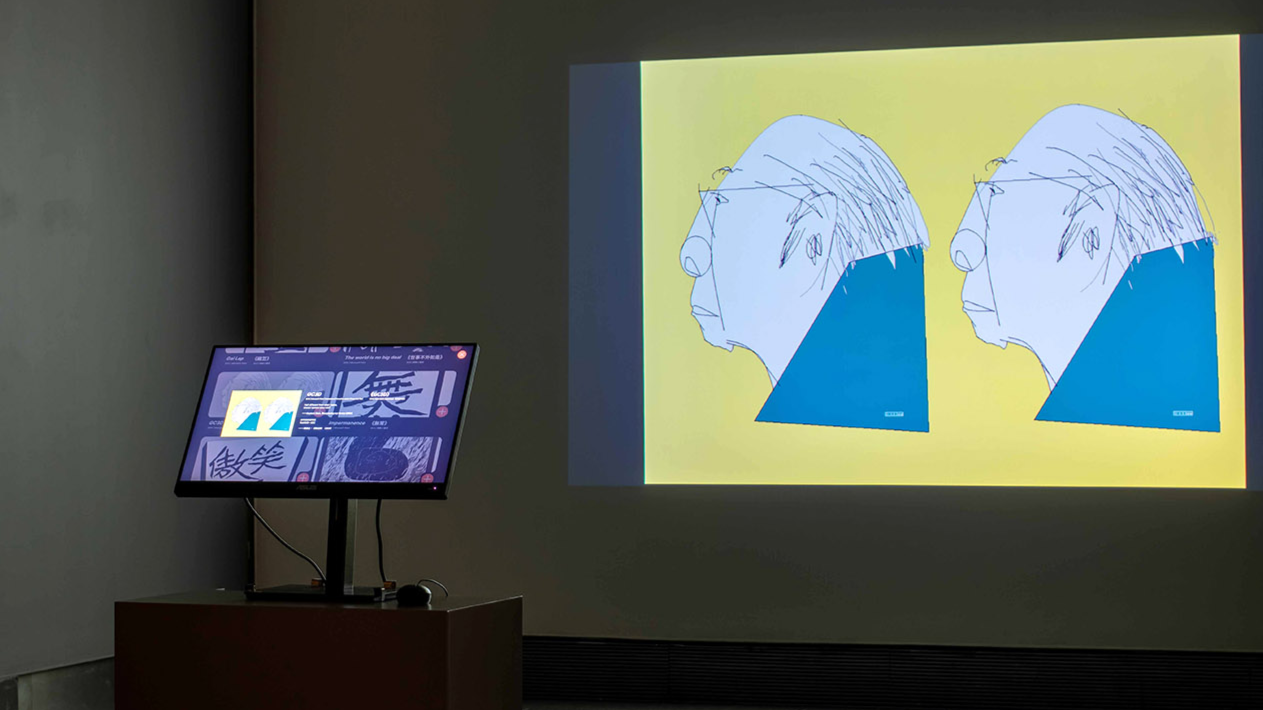

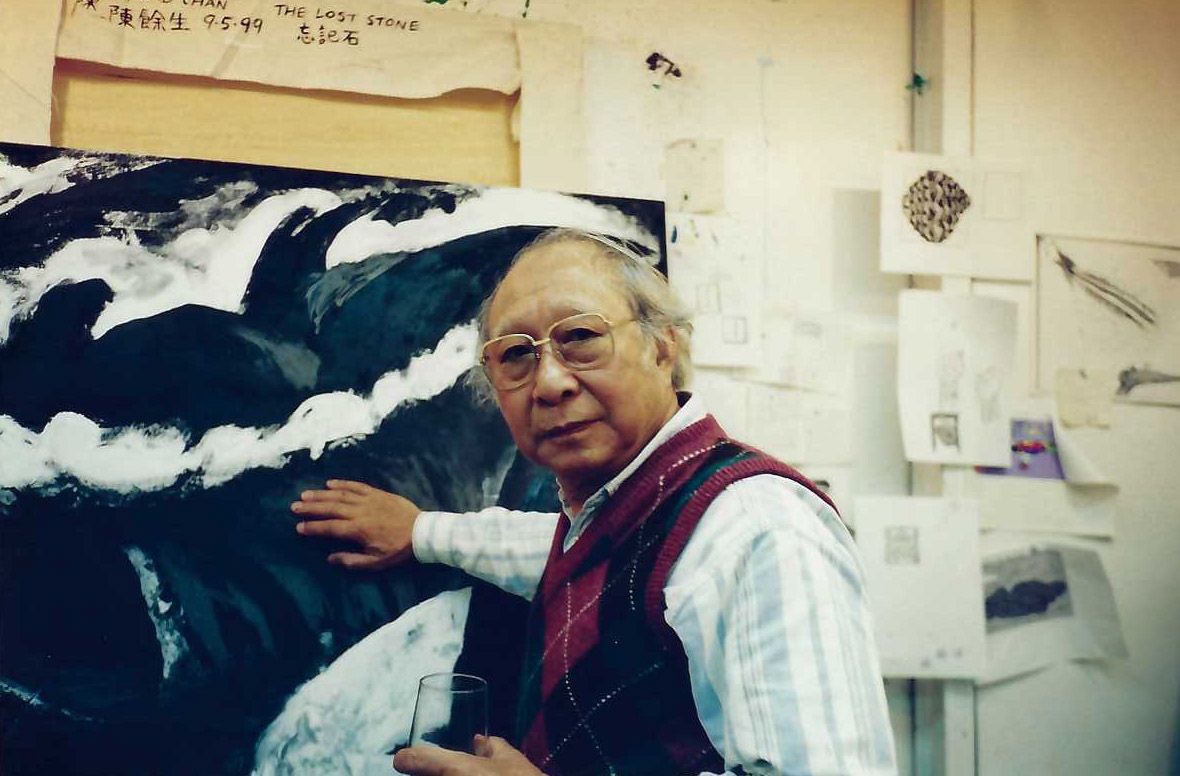

More than 100 works by the iconic modernist Hong Kong painter Gaylord Chan (1925-2020) are on show at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center (ASHK). Chan is among the city’s early exponents of contemporary art, recognized widely for the deceptive simplicity of his paintings. An engineer by training, Chan did not take up painting until he was 42. However, soon afterward, he came to be regarded as one of the most prolific artists in the city. Besides making his mark as a highly respected art teacher, Chan was also active in advancing the cause of contemporary art, having co-founded the Hong Kong Visual Arts Society in 1974. Always ahead of the curve, by 2001 Chan had embraced digital art, though this was also done out of necessity.

“He switched to using computers 2001 onwards, after he was diagnosed with lung cancer and was physically unable to paint on canvas,” says Joyce Wong, who curated the ASHK exhibition, Never End: The Art and Life of Gaylord Chan.

READ MORE: The green touch

Chan was quick to appreciate the flexibility of digital media. In a 2011 interview with a Hong Kong daily, he said that he enjoyed being able to “experiment with color combinations and alter them with a mouse click”.

Never too late to start

Those who knew him were probably less surprised by Chan’s mid-career switch from telecommunications engineering to art.

“He always had an interest in art but did not have the means to pursue it while he was young, being from a humble background,” explains Wong. Later, in 1968, when his first wife was battling cancer, Chan signed up for a three-year degree at the University of Hong Kong’s (HKU’s) Extra-Mural Studies Department, “hoping art can be an emotional outlet”.

His teachers on the program included architect and designer Tao Ho and British painter Martin Bradley. Ho was a student of the German-American architect Walter Gropius, founder of the influential Bauhaus school of design. Chan was exposed to modernist cultural concepts through his teachers and went on to formulate his own visual grammar, combining a rational, European approach with certain Chinese quirks in his works.

“He painted what he felt from his heart! His artworks are straightforward and honest,” says Chan’s widow, artist Josephine Chow. Her comment echoes a 1991 essay by Ho, in which he pays a glorious tribute to his student: “Each painting represents a spontaneous beat from his heart. He paints what he feels. ... He lets his heart guide his hand.”

Strange things, mystifying

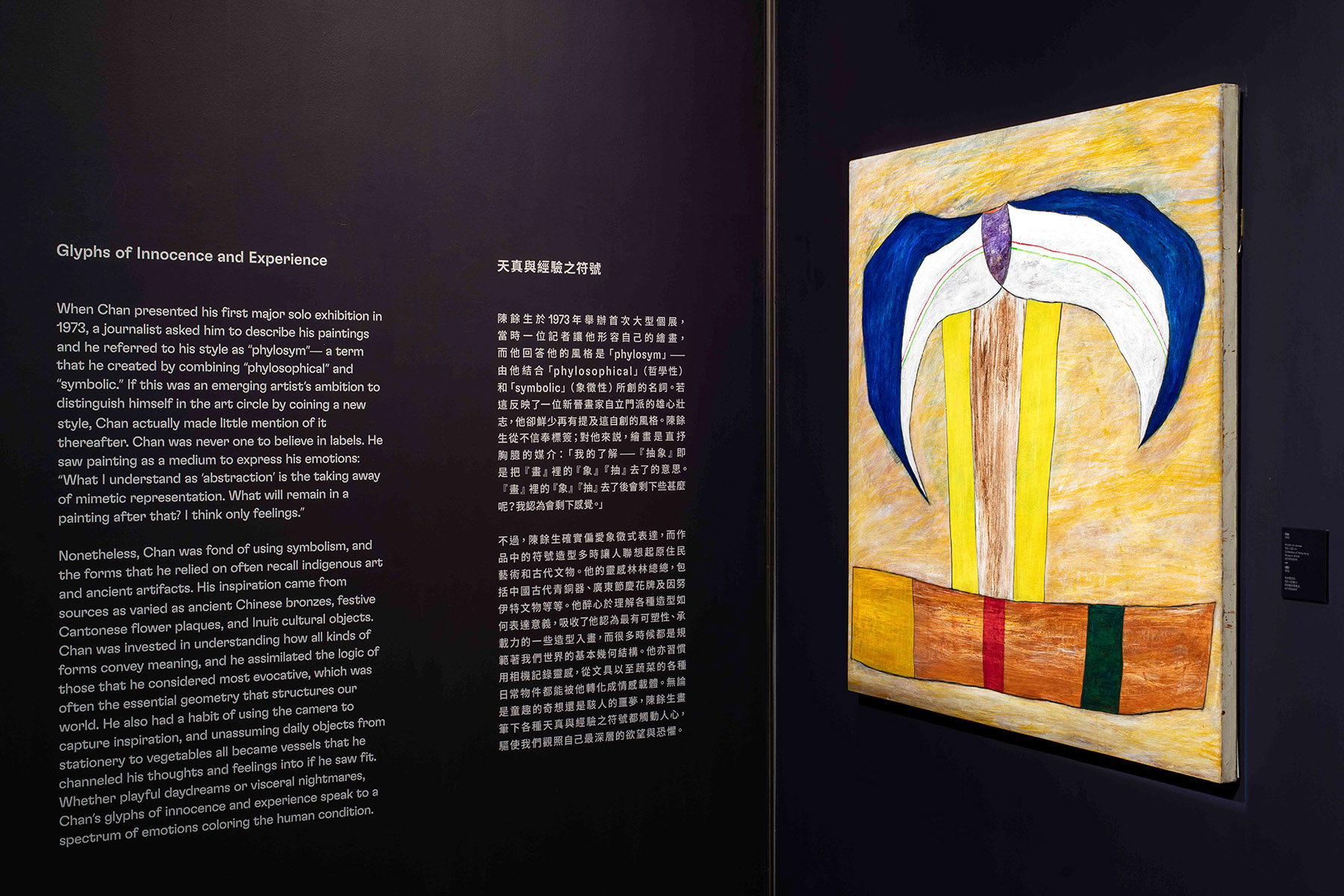

The enigmatic shapes created by Chan in his paintings are somewhere between the abstract and the figurative. Painted against spare, mysterious backdrops, some of them appear to embody a numinous experience. They could be read both as naive and playful as well as disturbing and nightmarish.

In 1973, Chan had labeled his style as “phylosym”, i.e., a combination of the philosophical and the symbolic.

So what was the artistic philosophy informing his creations?

“The purpose was always to express his feelings. Also, he was fond of using symbolism to convey ideas and emotions,” says Wong. Chan believed that honest works of art could trigger people’s innermost feelings, she adds.

Chow remembers how seeing Heart of Shaman (1984) for the first time made her feel an instant connection with the artist, whom she would eventually marry. “I was astonished by its colors and texture,” she says. “I loved the painting at first sight. It connected us. It has life in it! It is magic!”

Other exhibition highlights include an acrylic on canvas work called Carnival (1989), to which Chow also contributed. The painting was made to commemorate the opening of the Culture Corner Art Academy in Tai Po. The art school for young learners was Chan’s brainchild while Chow designed the training program. “We both felt happy and excited about a new journey of life!” says Chow, recalling a particularly fulfilling moment from her time spent with Chan. “Hence Carnival evokes a festive atmosphere. The painting can be read as a happy face wearing an ethnic hat, or two sea lions playing with balls.”

Spontaneous creations

Chan was drawn to objects with totemic associations. He found inspiration in the large-scale bamboo banners erected to celebrate festivals in Hong Kong and antique Chinese bronze vessels, for example. Both Carnival and Heart of Shaman conjure up the image of a world with similar mystical objects that come across as powerfully arresting. “They are the most obvious examples of Chan referencing the clear-cut geometrical lines of pre-historic Inuit and ancient Chinese artifacts,” Wong says.

Chow’s favorites from the show include Red Green Blades (1992) — a huge yellow circle with relatively tiny blades bearing red and green stripes stuck along its circumference. “It looks like a rotating organic life form full of enormous energy! The color is so luminous,” she says.

Chan was a colorist who often aimed to express a sense of joie de vivre through his paintings. Chow mentions that her husband believed in being spontaneous in his use of color, relying on instinct rather than meticulous planning, or even thinking about his process. “Gaylord called this the ‘color synergy effect’,” she says.

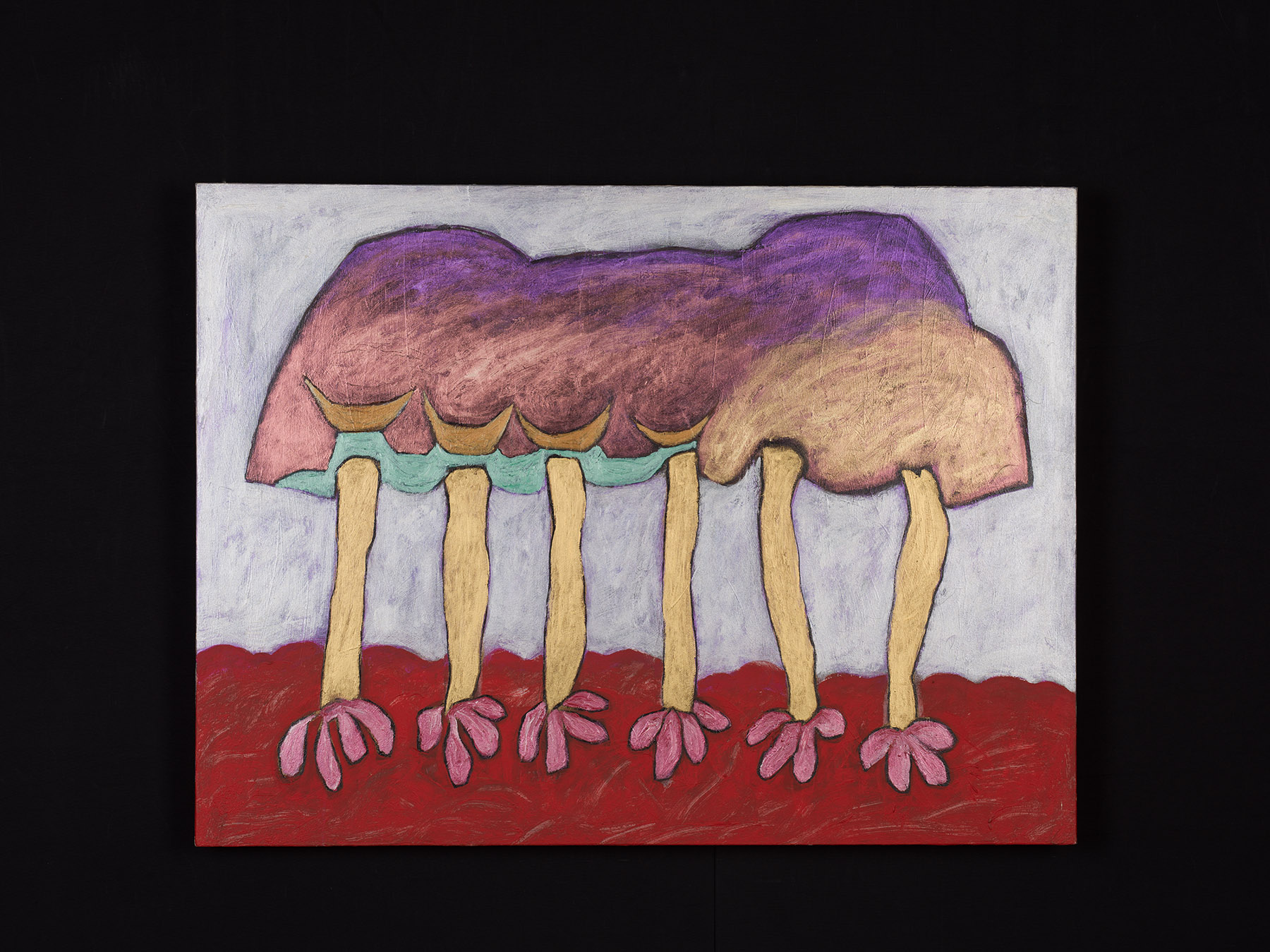

Another exhibition highlight, Growing Old (1993), is part of a series in which Chan experimented with metallic colors. In it we see a vaguely organic shape propped up on six stilts, or, alternatively, crawling on animal, or even human, limbs. The anthropomorphic object is as confounding as it is delightful.

Also on display at the exhibition are archival materials and footage digitized from video recordings showing Chan at work. Wong says these are meant to give the audience an idea of Chan’s teaching method, past exhibitions, and overseas travel. There are images of Chan at the construction site of the first submarine cable connecting Hong Kong, Luzon in the Philippines, and Okinawa in Japan. The project was inaugurated in 1977. Chan also helped set up a new telecom link between Hong Kong and Guangzhou, with a maximum capacity of 2,700 voice channels, in 1983.

Nurturing young artists

Wong believes Chan played a key role in raising awareness about contemporary art in Hong Kong. “He is a key figure in Hong Kong art history because he was a teacher, an educator, and an inspiration to many students and aspiring artists from the late ’80s until the early 2000s.”

According to Wong, Chan was one of the most illustrious graduates of HKU’s Extra-Mural Studies Department, in that he had the longest career compared with that of his fellow students and developed a unique style. The Hong Kong Visual Arts Society that he had cofounded went on to become one of the most active artists’ societies in Hong Kong and continues to support diverse art practices besides hosting many exhibitions and community projects.

Chow adds that her husband consistently supported all endeavors to stimulate young minds toward experimenting with and making new things. He would say, “Human wealth accumulates from creations.”

Cheng Yin-cheong, a professor of Education and Human Development at the Education University of Hong Kong, says, “Chan’s style neither follows Western trends nor affects Eastern idioms. He is his own man.” Wong, however, points out that Chan was influenced by a number of 20th-century European modernist masters, such as Picasso (1881-1973), Joseph Beuys (1921-86) and Anselm Kiefer (1945-). His life and oeuvre also resonated with those of Matisse (1869-1954). The image of a wheelchair-using Matisse making paper cutouts at a time when he could no longer paint brings to mind Chan’s last years, when he would not let his failing health get in the way of staying creative.

ALSO READ: Young at art

Chow never tires of recalling her husband’s favorite aphorisms: “Bring the goodness out from the material used,” and “Technique is never a problem; our mind is!” among several others. But his mantra, she reminds us, was: “Paint by instinct, finish a piece, and start another one soon!”

If you go

Never End: The Art and Life of Gaylord Chan

Dates: Through Sept 29

Venue: Chantal Miller Gallery, Asia Society Hong Kong Center, 9 Justice Drive, Admiralty, Hong Kong

asiasociety.org/hong-kong/exhibitions/never-end-art-and-life-gaylord-chan