A master painter and pioneer of the Hong Kong New Ink Movement, Lui Shou-kwan has a legacy that also includes a huge body of written work — be it inscriptions on paintings, teaching notes, or scholarly essays on theory and practice of Chinese ink art. A selection of these works is on show at Alisan Fine Arts. Mariella Radaelli reports.

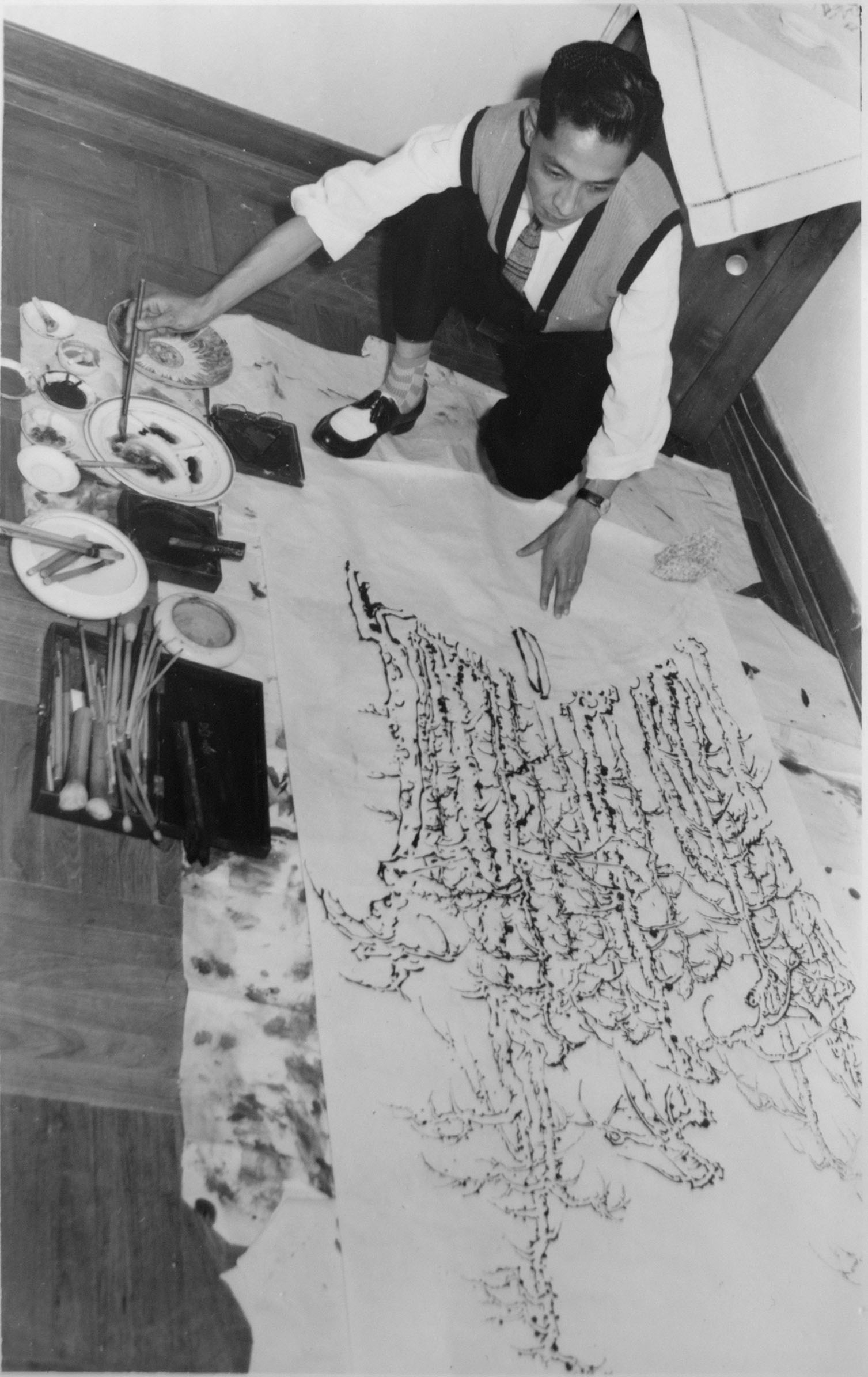

The legacy of Lui Shou-kwan (1919-75) — a legendary Chinese ink painter and pioneer of the Hong Kong New Ink Movement — also includes copious amounts of writing, be it inscriptions on his paintings, handwritten manuscripts of scholarly essays on art, teaching notes or published works. A selection of his written works is on show under the title Lui Shou-kwan: Artist Teacher Scholar at Alisan Fine Arts’ gallery in Central. The exhibition marks the 50th anniversary of Lui’s death in Hong Kong — where the Guangzhou-born artist had settled in 1948.

A close study of the works on display deepens the viewer’s understanding of Lui’s artistic philosophy, providing key insights into his experimental ink compositions, while also tracing his spiritual journey.

READ MORE: Re-viewing nature

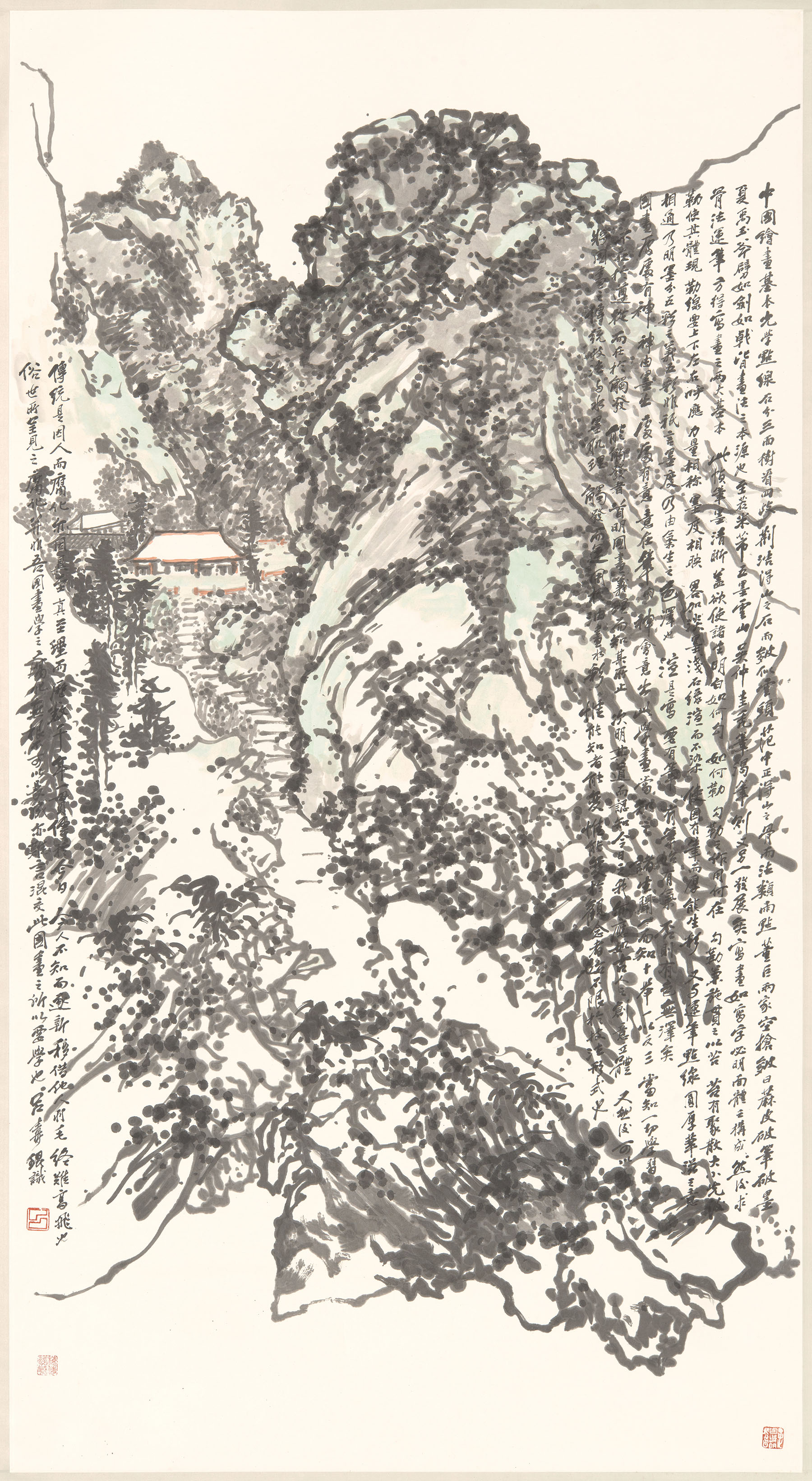

The exhibition showcases two dozen works created between 1951 and 1972, and sourced from the artist’s family collection. Daphne King-Yao, the director of Alisan Fine Arts, says that the writer and scholar in Lui are best represented in a work titled Landscape (1972). The image comes with a lengthy inscription that serves as a practical guide to learning the art of Chinese ink painting. Translated into English, its opening line reads: “The fundamentals of Chinese painting lie in the optics of dots and lines.”

A legacy built on solid foundations

The books section of the exhibition includes a monograph titled A Study of Chinese Painting (Hong Kong: Man Sang Printing, 1957), and Lectures on Chinese Ink Painting (Hong Kong: Lee’s Studio, 1972). The latter dwells on both theory and practice of Chinese painting, presented in a question-and-answer format. It was compiled as a tribute to Lui by students from his ink painting class at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

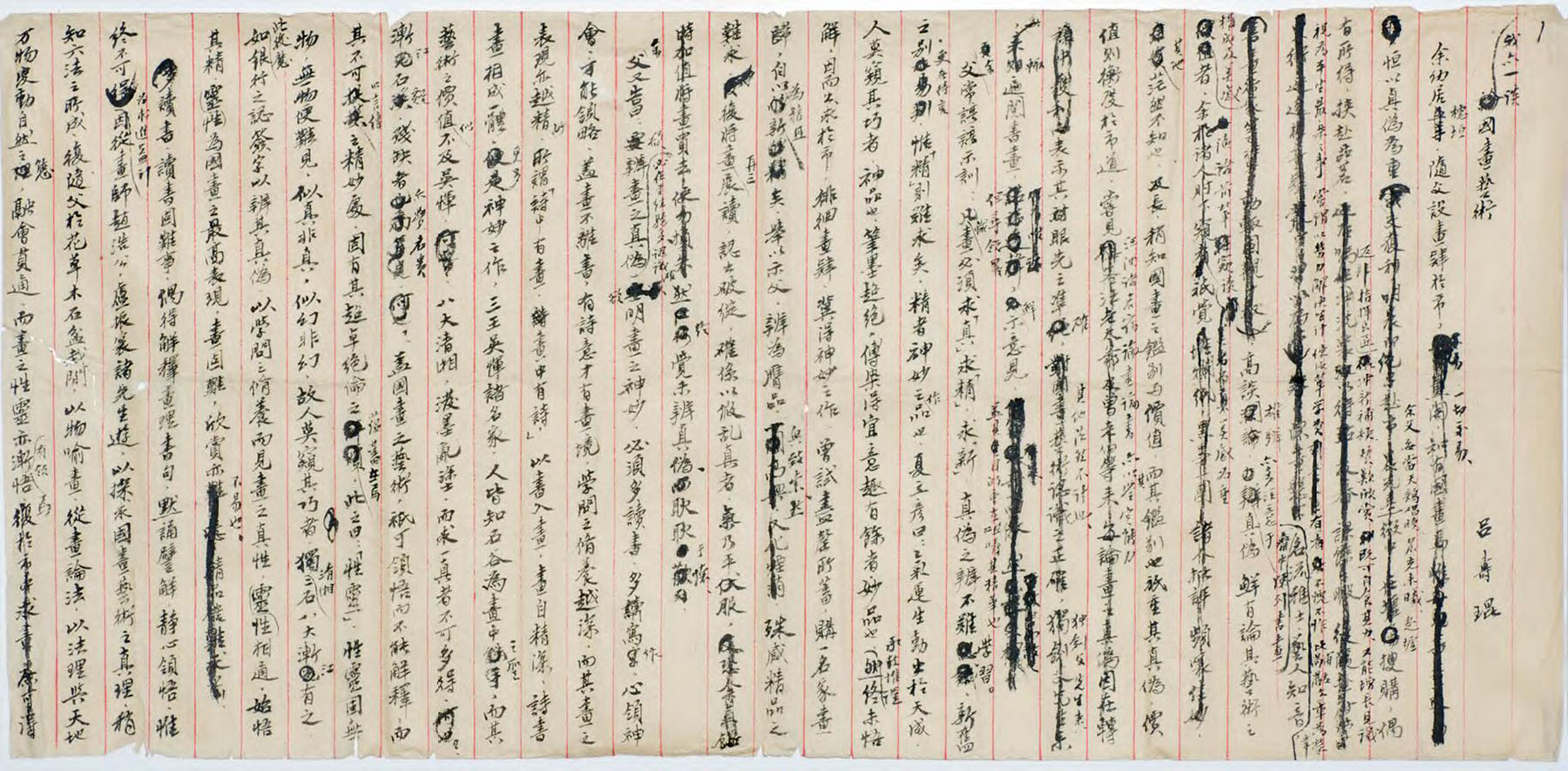

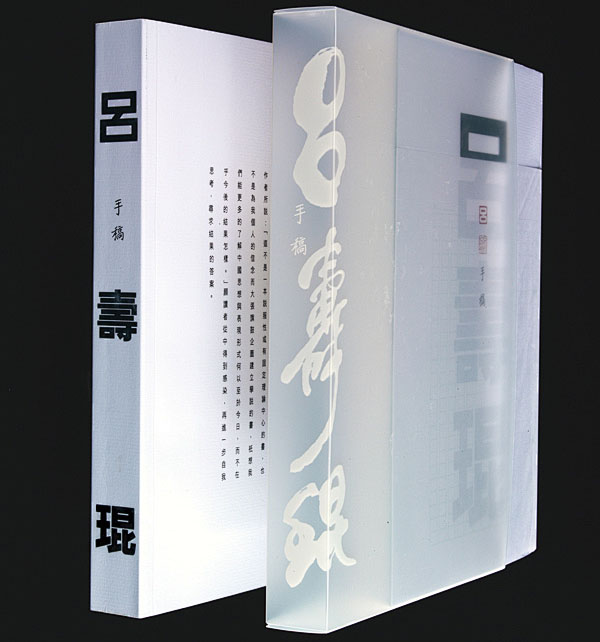

The display also features handwritten and typed manuscripts, some of which were compiled and published posthumously in 2005 by the CUHK Press under the title The Manuscripts of Lui Shou-kwan. The text reflects an inquisitive mind with eclectic tastes. Lui’s interests are shown to encompass Eastern and Western aesthetics, natural science, and films, among other subjects.

In an article called Hong Kong’s Chinese Painting, written to mark an eponymous exhibition held at the Hong Kong City Hall in 1967, Lui introduces what Eliza Lai Mei-lin — an independent art historian and an expert on Lui’s works — calls the concepts of “root” and “adaptation”.

She explains that “root” refers to the spiritual essence of traditional Chinese painting. This is informed by an artist’s ink-and-brush technique, their philosophical beliefs — be it Confucianism, Taoism, or Zen Buddhism — as well as their personality. “Adaptation”, on the other hand, refers to openness toward and integration of modern Western artistic ideas in an Asian context.

“Once an artist’s ‘root’ is firmly established, they are encouraged to freely draw from Western modern-art movements, and transcend the dichotomy between the East and West,” explains Lai. She adds that Lui believed prioritizing one’s roots over trying to adapt artistic elements from a different culture “helps build a strong sense of identity in artists, preventing them from losing their sense of direction while blending Eastern and Western influences”.

Eclectic tastes

Influential British art historian Herbert Read (1893-1968) is frequently cited in Lui’s writings. Read was a leading advocate for modern art movements — Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism, Constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism, among others. In the mid-’50s, Lui had co-translated Read’s book The Meaning of Art into Chinese with Li Shek-peng.

King recounts that while browsing through Lui’s archive, she had found an essay on abstract art, accompanied by a Cubist self-portrait that mentions Picasso. In it, Lui explains that his preference for abstraction is not owed to Western influence. Rather, his artistic sensibilities are shaped by the Chinese philosophy of art that has more to do with expressing the inner world of an artist, as illustrated in paintings such as Abstract 6 (1960s).

Deconstructing familiar forms

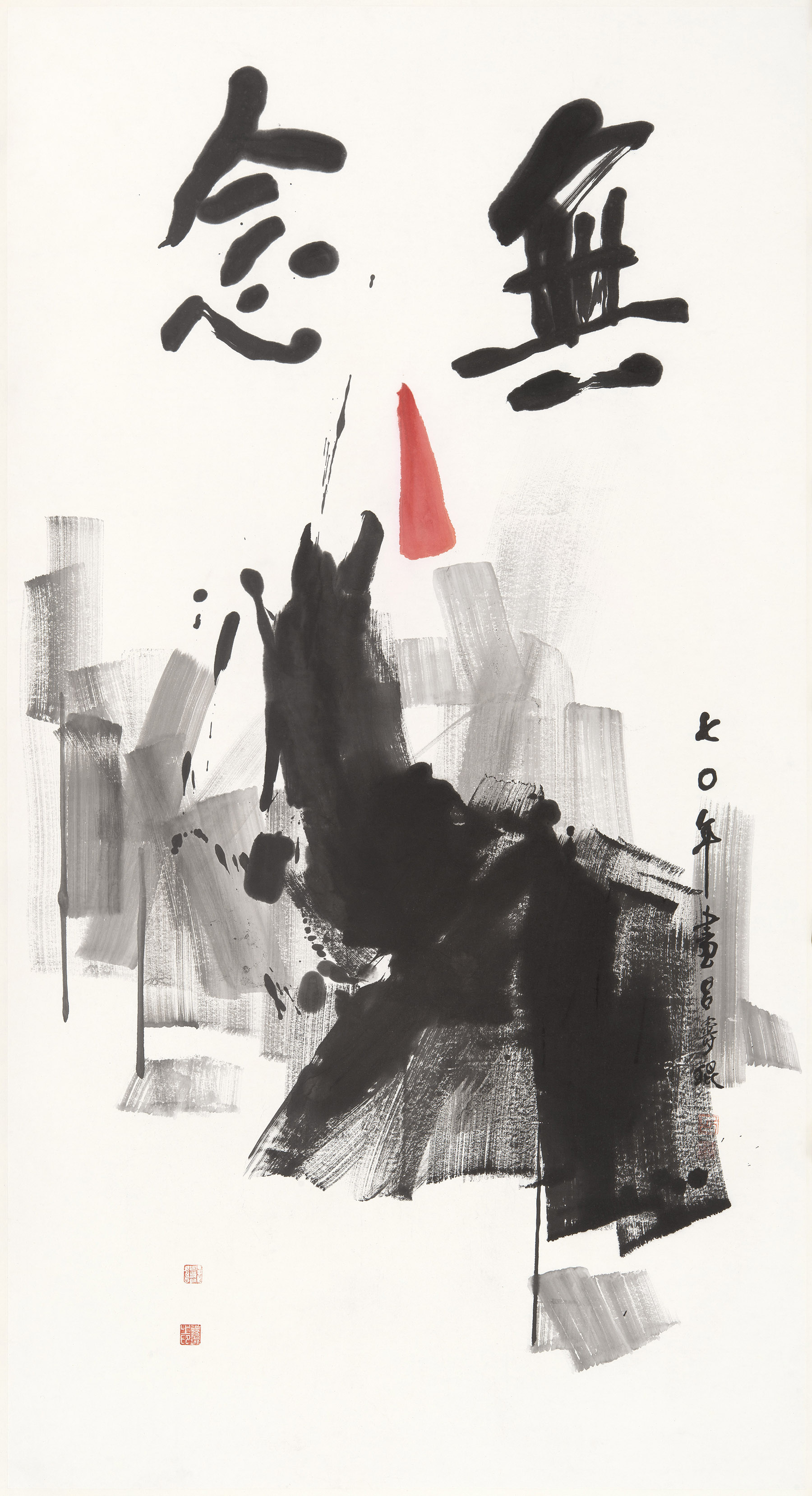

Lui’s deep engagement with ancient Chinese philosophy is reflected in some of the paintings on display. The three-word title of Beyond All Thoughts (1970) references the Zen Buddhist practice of meditating while seated — fei si liang in Mandarin. The painting is an attempt to describe a state of consciousness that exists between thought and its absence while practicing Zen-style meditation — a state in which one observes their own thoughts as if they were clouds passing through the sky, without trying to cling to them.

The painter reached his acme with his Zen painting series, which combines traditional Chinese philosophical thought and the visual language of Western modernism. Lai says that the series draws inspiration from artists such as Adolph Gottlieb, Pierre Soulages, and Franz Kline.

The series is marked by bold, abstract strokes that deconstruct the familiar forms of lotus flowers, buds, and leaves. Lai points out that the series resonates with the ideas in Lui’s prose piece, titled Yu Seng Ji (Notes on Meeting a Monk). “This allegorical prose piece was composed in 1962, when Lui was grappling with existential questions,” she explains, adding that the year also marks the beginning of Lui’s forays into Zen-style paintings. “This piece can be seen as a pivotal work that helped pave the way for his artistic maturity as a modernist ink painter.”

Lui’s father was a devout Buddhist, and after arriving in Hong Kong, the artist had befriended a Zen monk named Yuexi. The friendship might have inspired Yu Seng Ji, later included in The Manuscripts of Lui Shou-kwan. In Yu Seng Ji, the artist describes being visited by a Buddhist immortal in his dreams. In the dialogue that ensues, the artist expresses a profound desire to live in solitude, like a monk, and convey such longings through his paintings.

ALSO READ: Picasso’s Asian echoes

In the essay Life Philosophy and Thinking of Painting, also included in The Manuscripts of Lui Shou-kwan, the artist writes: “Zen means primarily to seek sudden enlightenment, that is, to become a Buddha.” In his view, an enlightened artist has reached the same state as the Buddha.

What Lui picked up from the philosophers and master painters who preceded him was deeply embedded in his practice, though both his paintings and writings are free of formal imitation. In the epilogue to Yu Seng Ji, Lui describes the Buddhist immortal whispering the words “Only when there is neither imitation nor repetition can a piece of creation be truly authentic” into the artist’s ear. Such words are key to understanding the mysterious yet powerfully compelling nature of Lui’s art.

If you go

Lui Shou-kwan: Artist Teacher Scholar

Dates: Through Dec 6

Venue: Alisan Fine Arts, 21/F, 1 Lyndhurst Tower, 1 Lyndhurst Terrace, Central

www.alisan.com.hk/en/exhibition-detail?id=262