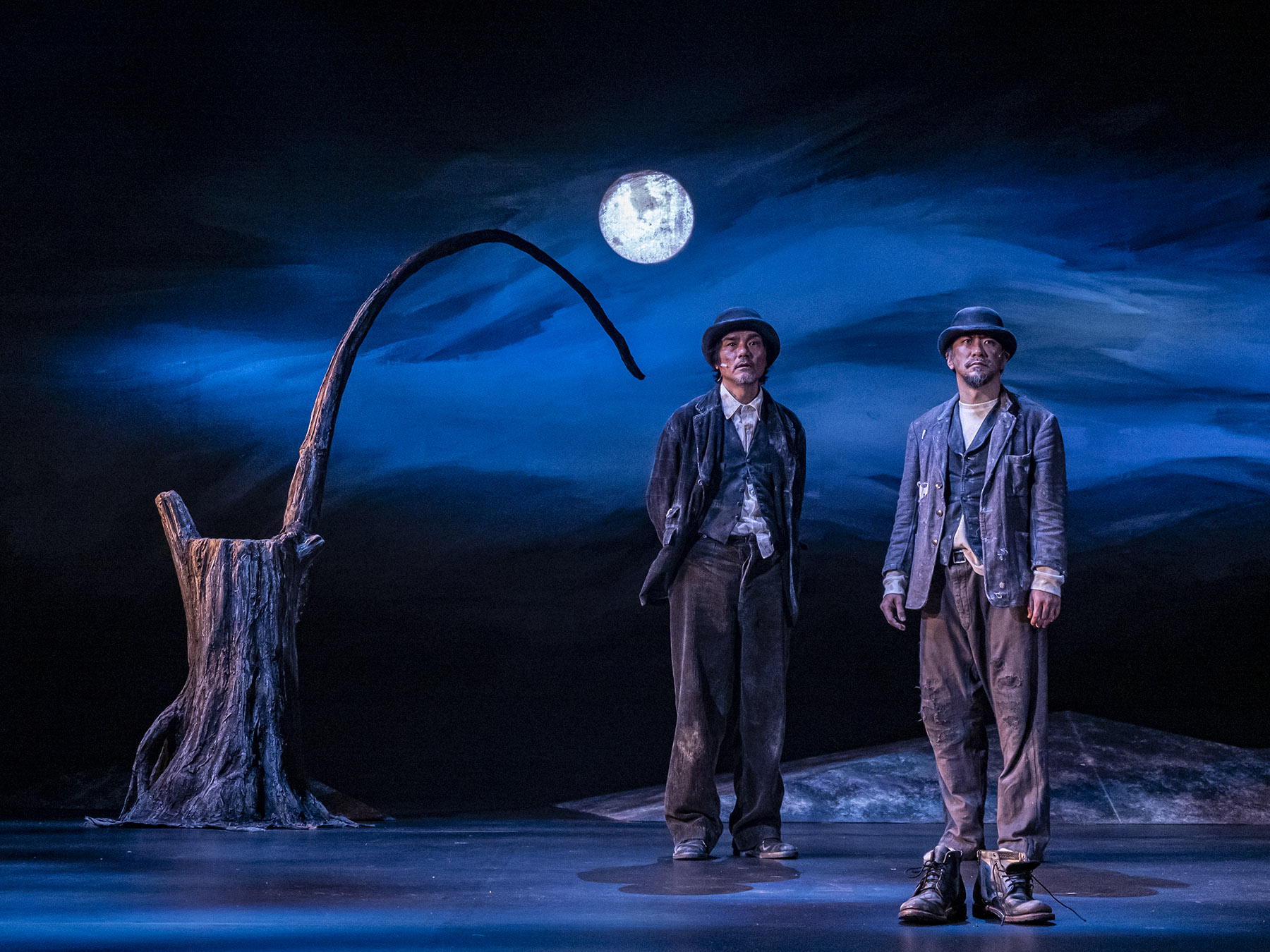

Among the recent Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio-produced stage adaptations of classic texts, Waiting for Godot is probably the one that most closely resembles the original material — Irish playwright Samuel Beckett’s 1952 play. Director Tang Shu-wing, who leads the eponymous company, is known for stripping down long and complicated plots to their bare essence, and bringing them to life primarily in the form of striking visual images created through choreographed movements by the actors.

With Godot, staged at the Hong Kong Arts Centre in December, Tang says his focus was on the words — both dialogues and stage directions. There is not a huge amount of either in Beckett’s play, in which two down-on-their-luck characters, Vladimir and Estragon, seem to be endlessly waiting for an elusive entity called Godot to show up and make a difference to their lives, although they are not exactly sure about what it is that they wish to be altered and how. The arrival of the overbearing Pozzo and his slave Lucky further obfuscates the confounding state of things. Ostensibly a repository of knowledge, Lucky is held on a leash and literally made to dance to the tune of his master. The second act is a reprise of the first with a few twists.

As the critic Vivian Mercier noted, Godot is a play “in which nothing happens, twice”. The dialogue is spare, the vocabulary quite basic, with the characters often merely repeating what they hear, like empty vessels knocking against each other. Voted as “the most significant play of the 20th century” in a 1988 poll conducted by London’s National Theatre, Godot is an extremely lean play in terms of words, and Beckett is known to have steadfastly, and consistently, refused to offer any gloss on what appears in the text.

Hence, Tang directing a Beckett is a meeting of two minimalists. “Beckett’s simplicity echoes well with mine,” says the director. “Staging a Beckett requires you to listen to his words, respect his staging direction, before you can transcend the material to a more profound and poetic level.” He seems to suggest that it is only by carefully considering the words that one begins to appreciate the meaning behind the apparent absurdity and vagueness — realize that the play is about “authentic life experiences universal to all humanity, revealed in theatrical situations and languages”.

Tang, who also translated Beckett’s play into Cantonese for the stage adaptation, says that the musicality of Cantonese, its capacity to express diverse ideas and emotions of grassroots and marginalized people and also to pack multiple layers of meanings into a single word or turn of phrase resonate with Beckett’s original words.

The director assembled a powerhouse cast of actors to breathe life into those potent words. Seasoned film actor Lam Ka-tung as Vladimir, actor-director-academic Chu Pak-him as Estragon, film and television star Choi Hon-yick aka Babyjohn as Pozzo and Ngai Ping-long, who has made his mark as a DJ and stage actor in Hong Kong and Canada, as Lucky performed like a well-synced orchestra, technically perfect and high on emotional empathy for the content they were delivering.

Tang says he visualized the character of Pozzo as a sleek “fintech guy” — the sort who seem to exercise considerable influence on the ways in which our technology-driven existence is designed and controlled today. Ngai was chosen to essay Lucky on account of the actor’s mystic aura.

“The absurdity around us today is even more intense than in Beckett’s time,” Tang says. “On the table there are grand discourses of all kinds, while there is an unknown world operating underneath it.”

He sees parallels between Godot and the unending, and often meaningless, cycles that many human beings find themselves in today.

“Nothing has really changed: the difficulty in verbal communication, the collapse of spiritual faith, the illusion of time and the unavoidable cycles of human beings going through ups and downs.”

Contact the writers at basu@chinadailyhk.com