Iconic structure is testament to nation's galvanizing victory against Japanese invaders, Yang Yang and Li Yingqing report.

Before 2015, Dong Rongrong knew little about her great-grandfather Liang Jinshan, who died in 1977. On Oct 3,2015, Dong, then 29, heard that Liang Youcheng, Liang Jinshan's son, the elder brother of Dong's maternal grandmother, was invited to Beijing as one of the five people representing overseas Chinese to watch the military parade that marked the 70th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese people's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the World Anti-Fascist War.

Realizing that her great-grandfather must be a very important person, she began to seriously learn about his extraordinary life, especially after she joined the Overseas Chinese Federation in Longyang district of Baoshan in Yunnan province.

Born into a poor family in a village in Longyang district in 1882, Liang Jinshan (1882-1977) became an orphan at 16.

READ MORE: Legacy of courage

In 1903, to escape persecution by local despots, he fled to Burma (now Myanmar), where he endured starvation and backbreaking labor as a road builder, dockworker, and oil refiner.

Liang Jinshan's pivotal moment came at a British-owned silver factory where he accidentally solved a critical smelting crisis. Later, despite his limited education, his integrity and foresight saved 3,000 miners from a catastrophic collapse in 1916.

Honored with engraved weapons and promoted to general manager, Liang gradually accumulated wealth, becoming one of the richest Chinese men in the country.

"He was, first and foremost, a genuine farmer of down-to-earth integrity. Through sheer diligence and hard work, he achieved prosperity step by step — a testament to his tireless perseverance. Despite never receiving a formal education, he ultimately mastered conversational fluency in five languages," Dong says.

Yet even after attaining wealth, he never turned his back on his homeland. When the war against Japanese invaders erupted, he provided funds for the defense through substantial donations, says Dong, now Party secretary of the federation.

On May 4, 1942, to block the Japanese invaders and save the country, the Chinese army decided to demolish the strategic Huitong Bridge over the Nujiang River in Yunnan province.

It was the only bridge connecting China and the world as the Japanese aggressors had cut off all the other routes for international aid.

However, if the bridge remained intact, the Japanese invaders would reach Kunming in 10 days, which was close to Chongqing, the temporary capital for the then Chinese government since the war's full-scale outbreak in July 1937.

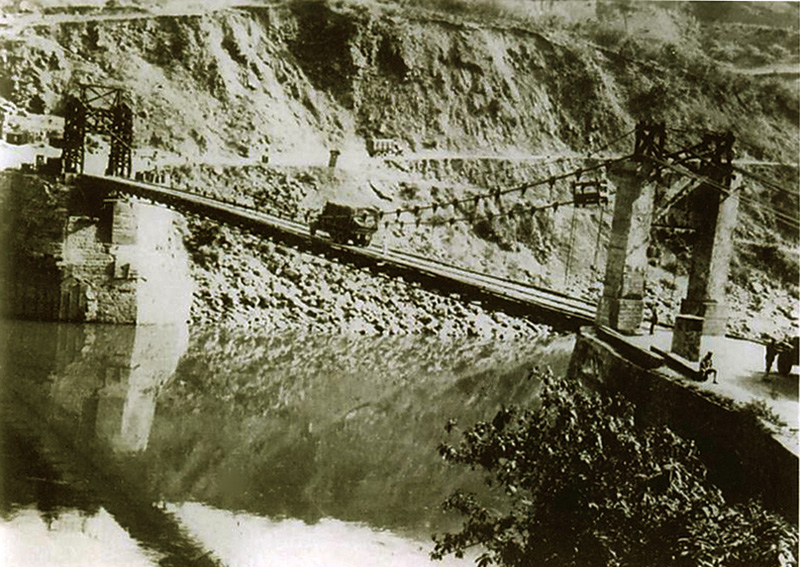

Before the Chinese army blasted the bridge with explosives, a senior official of the Kuomintang government, Yu Feipeng, called on Liang Jinshan, who initially financed the construction of the cable bridge, the first of its kind in China.

For generations, the people of western Yunnan longed for a bridge to connect the two sides of the tumultuous Nujiang River.

In June 1932, the head of Longling county went to Burma asking Liang to endow the bridge. Liang agreed. He sold two businesses and one factory, and donated the proceeds to the bridge construction.

After three years of hard work, the bridge, 123 meters long and 5.67 meters wide, was completed in 1935.At the inauguration ceremony, rejecting the proposal to name the bridge after him, Liang Jinshan named it Huitong Bridge, meaning "the connection brings benefits and prosperity".

In 1937, when the Chinese government decided to build a highway connecting Kunming to Burma to transport strategic supplies purchased abroad and received as international aid, the Huitong Bridge became the "throat" of the route.

Between December 1938 and May 1942, a total of 452,000 metric tons of supplies passed over the highway as well as the bridge, accounting for more than 90 percent of all international aid. Ninety percent of the strategic supplies were transported by more than 3,200 overseas Chinese from Southeast Asia who volunteered to do the work.

Over 100,000 tons of supplies were transported from Rangoon using 200 Dodge T-234 trucks that Liang generously provided.

In addition to this, he donated an aircraft and purchased half of the National Salvation Public Debt allocated to Yunnan. Furthermore, Liang contributed a fixed sum of money each month to support resistance efforts until the war's conclusion.

Due to his contributions and active role as the leader of overseas Chinese to fight the aggression, the Japanese army put a price on his head, but he evaded capture.

Liang abandoned all his businesses and estates in Burma and returned to China.

In May 1942, hearing of the decision to detonate Huitong Bridge, Liang was emotional but agreed, saying that he believed that, after winning the war, it would be restored.

Huitong Bridge became a legend during China's resistance against Japanese aggression. Yu Ge, author of Huitongqiao Zhizhan (The Battle of the Huitong Bridge), compares the critical battle around the bridge in 1942 as China's "Dunkirk".

"In the history of the resistance war, the Battle of Huitong Bridge held a unique and irreplaceable value — much like the Dunkirk evacuation in the European theater. It preserved forces for the great counteroffensive two years later and planted the seeds of ultimate victory," said Yu at the book launch ceremony last year.

Historians see the demolition of the bridge as "one minute that changed history".

The Nujiang Grand Canyon, where Huitong Bridge stands, has long been dubbed "Nature's Impenetrable Moat".

In 1935, when Liang built the modern cable bridge, the steel cables, manufactured under British supervision in Burma, were transported from Lashio to the banks of the Nujiang River.

At that time, Burma Road had not yet been constructed. According to an article by Lin Wenqiao, a professor from Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, the Eight Great Caravans of Western Yunnan linked 50 horses into a continuous line, securing sections of steel cables on both sides of each horse's back. Guided by two or three caravan masters per animal, the horses moved in unison under coordinated commands. Their path descended from Songshan Mountain to the Nujiang River — a narrow, winding trail with gradients exceeding 30 degrees — where the slightest misstep by any horse, whether too fast or too slow, risked catastrophe.

In October 1938, to integrate with the Burma Road project, the original Huitong Bridge — which could previously only accommodate packhorses — was reinforced and reconstructed into a steel-cable suspension bridge capable of carrying 10-ton trucks, with 1,000 chestnut timbers used for the bridge deck sourced from remote virgin forests — a seven-to-eight-day trek on foot — and then hauled by hand to the construction site.

While German forces swept through Europe, Japanese troops remained bogged down in the Chinese theater, unable to advance their "Southern Expansion Policy "into Southeast Asia. The Japanese government believed that only by severing international aid to China could they force its capitulation.

In January 1942, after bombing Burma Road with 100 aircraft for months, in order to sever it completely, the Japanese invaded Burma. To keep the lifeline open, the Chinese Expeditionary Force went to fight in the country but had little success.

By the end of April, Burma Road fell into chaos, packed with retreating expeditionary troops, fleeing refugees and evacuating government staff.

At the start of May, the fierce 56th Division of Japanese troops moved quickly along Burma Road toward Huitong Bridge, led by armored vehicles and transported by about 100 automobiles, dreaming to travel across the Nujiang River, occupy Kunming, and seize Chongqing.

On May 5, 1942, the division arrived at the west bank of Huitong Bridge.

The Chinese army knew it had to halt the enemy on the west bank at any cost, and confronted with a much stronger force, blowing up the bridge became the best choice. On the Japanese side, they wanted to capture the bridge, but a fierce assault on Huitong Bridge would inevitably trigger the Chinese defenders to demolish it, so they tried to pass the bridge stealthily camouflaged as refugees, which created dilemmas for defenders timing the demolition.

There are varying versions about the timing of the demolition.

One version is that at noon, the camouflaged Japanese troops were exposed, so they fired. Hearing the noise, the Chinese defenders activated the explosives, smashing the 56th Division's dream.

It was not until August 1944 that the bridge was restored during the Battle of Songshan Mountain between June 4 and Sept 7, 1944. After its reconstruction, this bridge could handle ammunition transport for 11 front-line divisions, achieving a monthly capacity exceeding 10,000 tons — making an indelible contribution to the final victory.

Today, the once bustling activity of vehicles and pedestrians on Huitong Bridge has faded into history, yet the legendary life of community leader Liang Jinshan remains widely celebrated by locals.

ALSO READ: Digital diary of unsung courage

To commemorate him, a white marble statue was erected in Taibao Park, Baoshan city — honoring this patriotic overseas Chinese leader who never forgot his roots.

Now, a route in west Yunnan province has been designed for tourists to travel while learning about that gripping chapter of the resistance war. Burma Road and Huitong Bridge are two important parts of the tourism route.

Driving along Burma Road, one can trace the path of wartime supply convoys, visit key sites such as former military logistics and repair hubs, and explore blocking-action trenches and allied artillery emplacements.

At Huitong Bridge, archival footage of the battle in 1942 can be viewed, and the Nanyang Volunteer Drivers and Mechanics Memorial Hall honoring overseas Chinese truck drivers is open to visitors.

Crossing the bridge, one can feel the Nujiang River's torrential waters beneath their feet and reflect on wartime sacrifices. Standing before the West Bank Monument, one can see the bridge's brutal history.

Contact the writers at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn