As a metaphor for young Chinese architects, the Beijing bird symbolizes the risky survey they carried out at night during the Japanese aggression to preserve the most treasured landmarks, Chen Nan reports.

The Beijing swift (Apus apus pekinensis) is a bird that almost never lands. It can fly thousands of kilometers without resting, skimming across continents and seas. When it finally returns to the city, it does not choose forests or lakes. It chooses old roofs for nesting beneath the eaves of palaces along the spine of Beijing's ancient Central Axis.

From Jan 31 to Feb 3, the National Centre for the Performing Arts will premiere its original drama, Beijing Swift, the first stage production created to celebrate the Beijing Central Axis, which was inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List in 2024.

READ MORE: Vital clues shed light on avian migration routes

The Beijing swift, as a metaphor, symbolizes a group of young Chinese architects who, in 1939, in the old city of Beijing, which was then called Beiping, moved through the city at night carrying rulers and pencils to secretly measure the treasured buildings along the Central Axis in an attempt to preserve civilization on paper.

Stretching 7.8 kilometers from north to south through the heart of Beijing, the Central Axis is the city's architectural and symbolic backbone. On it sit palaces, ritual spaces, public buildings, and gardens that govern the layout of the old capital.

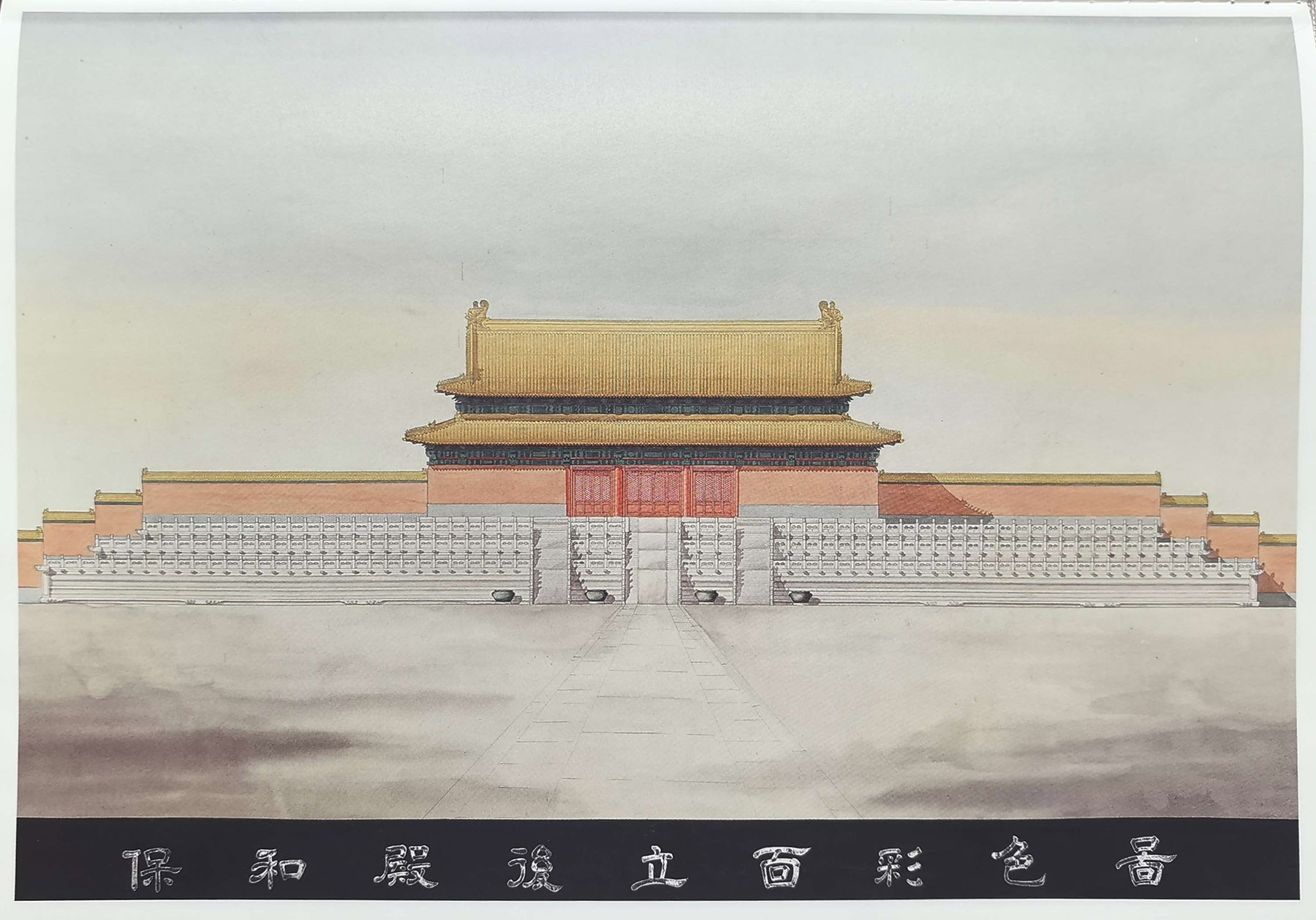

From the Bell and Drum Towers in the north to Yongdingmen Gate in the south, it has 15 key components, including landmarks like Jingshan Hill, the Forbidden City, Tian'anmen Gate, and Zhengyangmen Gate.

The play grows out of a little-known but deeply moving historical truth, according to playwright Tang Ling.

Set in 1939, Beijing Swift unfolds at a time when ancient walls were crumbling, and the future was deeply uncertain. Yet, in this Japanese-occupied city, an architect named Zhang Di forms a secret survey team to document Beijing's most important buildings along the Central Axis before they are damaged, altered, or erased by war. They work at night, moving through shadows, measuring every beam, every column, every brick and tile.

"They believe in one simple idea: drawings can bring everything back to life," says Tang. "Over four years, they record the soul of the city on paper. What they are preserving is not just architecture but the invisible order behind it: the ancient Chinese understanding of space, balance, and meaning embodied in the Central Axis."

The protagonist, Zhang Di, is based on Zhang Bo (1911-99), one of the most important architects in modern Chinese history and a student of Liang Sicheng (1901-72). In the 1930s, Liang was the first to articulate the Central Axis not merely as an urban layout but as a civilizational idea, Tang notes.

"There were people who, in the middle of war, insisted on protecting ancient buildings while risking their lives. What supported them was a belief: as long as cultural genes survive, the nation survives. Their courage and sense of responsibility deserve to be remembered," Tang says.

From 2023 on, Tang and the play's creative team immersed themselves in extensive research, including the study of architectural history, wartime Beijing, and the technical discipline of surveying.

They traveled to Tianjin University to trace the legacy of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture, one of the earliest and most important academic institutions devoted to the systematic study and documentation of traditional Chinese architecture in the 20th century. They examined archival materials, practiced field measurements, and conducted in-depth research in the Forbidden City, consulting contemporary experts to anchor the play in professional, historical reality.

"In the play, the swift becomes a metaphor for endurance and faith," says director Fang Xu, who is known for his adaptations of Lao She's works, including Rickshaw Boy and Niu Tianci. On a more poetic and symbolic level, he says, the image of the Beijing swift runs through the entire production.

Although the drama still carries a strong sense of "Beijing flavor", Fang notes, it does so in an alternative way. "One of our biggest challenges was finding the balance between professional architectural details and dramatic storytelling," he says.

"Ancient buildings are enormous. Even the roof ornaments of the Hall of Supreme Harmony are nearly three meters tall, making the human figure look small by comparison. This contrast is visually powerful, but it is impossible to re-create such a true-to-life scale on a theater stage," Fang explains. "The question of where reality ends and poetry begins became part of the production's core language."

ALSO READ: Old Beijing, reimagined

Guo Shuojie, who plays protagonist Zhang Di, followed the production team to conduct research at Tianjin University and the Forbidden City. There, he learned that surveying ancient buildings often means crawling into narrow spaces beneath old rooftops — places that never see daylight and are filled with dust, mold, and even the smell of bat droppings, making it almost impossible to stay for long.

"An expert told me that he often finds the names of craftsmen and the dates of their work written on old beams," Guo says. "At that moment, it felt like he was meeting those ancient builders across time. That's when I began to understand the belief that holds my character together."

Contact the writer at chennan@chinadaily.com.cn