Hong Kong’s first homegrown anti-cancer drug has saved hundreds of lives. Shadow Li talks to Professor Kwong Yok-lam about his 30-year journey to develop the treatment.

Editor’s note: The future belongs to those who dare to shape it. In this series, China Daily highlights the bold thinkers and doers transforming industries and breaking barriers. Meet Kwong Yok-lam, an eminent Hong Kong hematologist known for developing oral-ATO, the city’s first homegrown anti-cancer drug derived from arsenic trioxide.

Apale-faced patient battling with leukemia flew from the Philippines to Hong Kong in search of a cure for the deadly blood cancer disease. He owes his life to eminent Hong Kong hematologist, Professor Kwong Yok-lam who miraculously saved him with a prescription of arsenic trioxide — a newly-developed drug for acute promyelocytic leukemia, a once incurable disease.

Blood results had shown that his level of hemoglobin — a protein that reflects the amount of red blood cells in the body — was extremely low, just one-third that of a normal healthy person, warranting immediate medical treatment.

ALSO READ: Carving out dreams

Professor Kwong recalls how the patient pleaded with him, gasping with a trembling voice, and said: “I had spent all I had borrowed for a return air ticket to come and see you. I had to catch a plane back to the Philippines right away as I don’t even have enough money to spend a night in Hong Kong.”

The man’s plight moved Kwong who immediately prescribed him with a month’s oral formulation of arsenic trioxide, or oral-ATO; ARSENOL®. Within a month, the patient’s health had dramatically improved and, by the following month, he had almost fully recovered.

Patients’ hope

Oral-ATO is Hong Kong’s first homegrown prescription anti-cancer drug. In February last year, it obtained orphan drug designation from the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, as well as an investigational new drug designation from the FDA, becoming Hong Kong’s first self-developed drug to receive such recognition and marking a significant step towards wider global adoption.

Three decades of perseverance in developing the wonder drug had paid off for Kwong, who helms the hematology, oncology and bone marrow transplantation unit at the Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, the University of Hong Kong, and his team.

In 1997, Kwong, then a young doctor, had read an international paper by a Chinese mainland medical team about arsenic trioxide’s success against acute promyelocytic leukemia. Intrigued, he raised it with his mentor who then revealed a local medical archive — Hong Kong had, in fact, used an oral arsenic trioxide formula for the disease in the 1950s with exceptional results. “We had very few drugs for leukemia then,” Kwong recalls. “One of them was oral arsenic trioxide, and it worked powerfully against cancer cells.”

However, the drug, which was once produced at Queen Mary Hospital where Kwong worked, had been lost. This drove him to reinvent an oral formulation. While clinics on the mainland had administered arsenic trioxide intravenously, Kwong wanted to do his best for patients with an oral version that would spare them the emotional and financial strain of having to be hospitalized for two weeks.

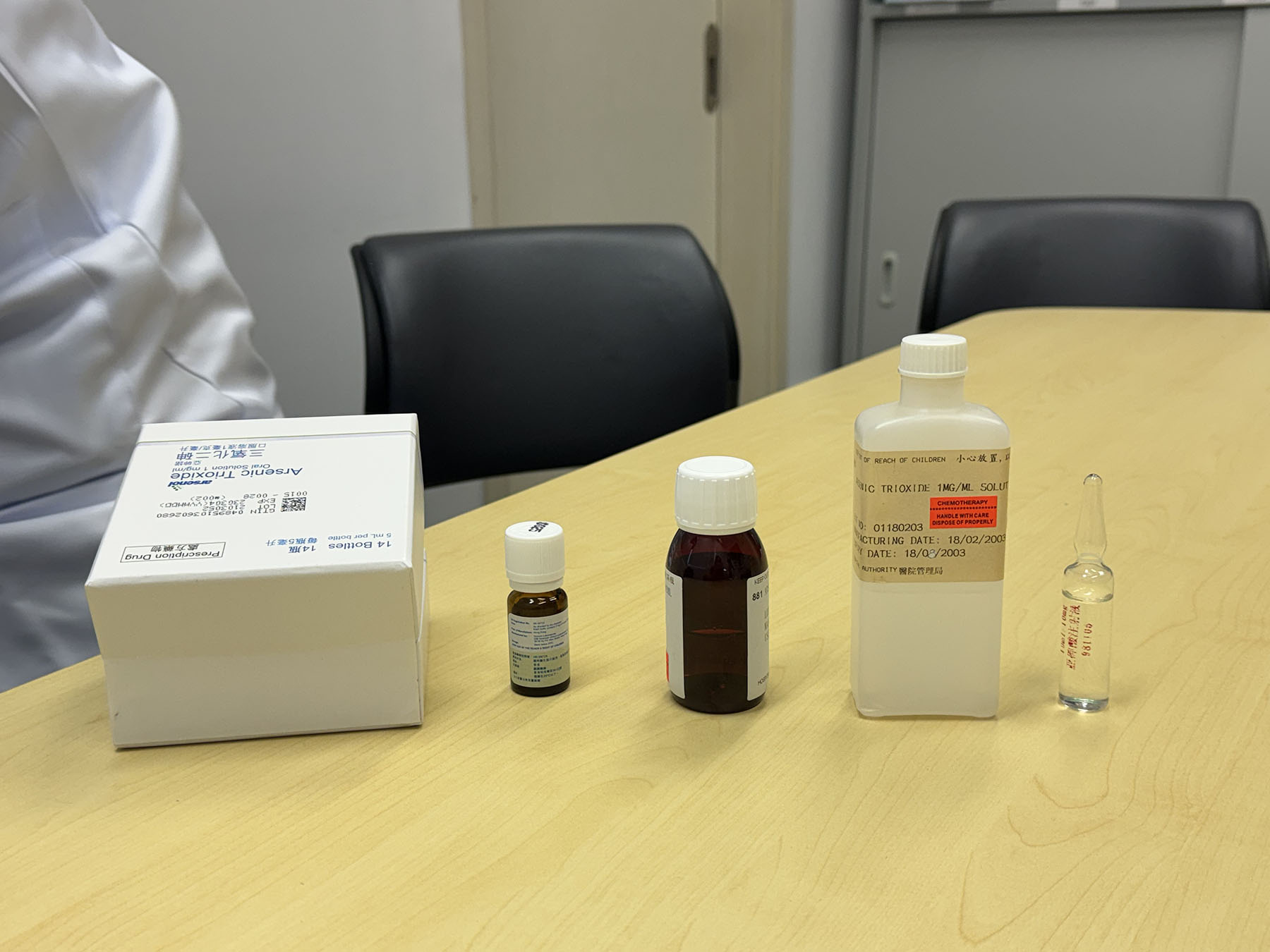

He sought samples from the mainland and, as a meticulous scientist, he wanted to see the effects firsthand. Carefully kept in a bubble wrap, the sealed glass container with the samples was nearly intact as a token and living embodiment of the start of a three-decade journey. He would bring it with him every time he met with the media.

With a precise dose, the efficacy of arsenic trioxide — a toxic compound — had been proven, having been successfully applied to leukemia patients. But, in the long run, relying on the mainland for supplies of the drug wouldn’t be sustainable, considering the not-well-established infrastructure and difficulties in cross-boundary logistics at the time. Moreover, Hong Kong had then lost its technology and formula for the oral formulation.

Kwong knew that a local solution was essential. “Without it, my hands would be tied in treating my patients,” he says. With the help of another pharmacology professor, Kwong spent nearly three years pulling it off. Despite a demanding schedule of treating patients and teaching, he devoted his spare time to developing the drug. With Hong Kong having virtually no pharmaceutical industry then, Queen Mary Hospital had to produce it itself. By 2001, an oral arsenic trioxide formulation was available again as an in-house preparation.

Hong Kong records 25 to 30 new cases of acute promyelocytic leukemia each year. With oral-ATO, newly diagnosed patients can expect an overall survival rate of 97 percent, compared with an up to 30-percent fatality rate using traditional therapies. As of February last year, more than 430 patients had received oral-ATO treatment, with 90 percent of them cured.

Developing the cure

Since 2018, the HKUMed research team has made strides on perfecting the regimen. The new regimen for patients, made of oral-ATO, all-trans retinoic acid and ascorbic acid, lowers the risk of resurgence to less than 2 percent. It will take 70 days for treatment, requiring hospitalization of 14 to 21 days — compared to the 100 days needed for intravenous injection.

A woman, surnamed Wong, who was diagnosed with leukemia in April 2023, had four chemotherapies at a private hospital, followed by intravenous injections of arsenic trioxide, requiring her to be hospitalized for 100 days. The torment of being subjected to hours of daily injections was unbearable, in addition to the side effects of hair loss and physical pain caused by a sudden high dose of toxic arsenic trioxide. She also had an exorbitant HK$2.6-million ($334,000) bill for two weeks’ treatment.

Through a referral from another leukemia patient who had recovered after taking oral-ATO and subsequently got married, Wong sought help from Queen Mary Hospital and had her hands on the drug. Within a week, she was able to return to work. Without having to stay in hospital, she took the drug for 14 days and a second course of treatment after six months to consolidate the effect.

Wong’s blood test results have shown no sign of abnormality so far. “I’ve regained my life,” she says.

Oral-ATO is now in its fourth generation.

“I would have long given up if I had been purely a researcher. Yet, seeing my patients day after day, I just can’t turn them away and let them die without trying my best,” says Kwong.

He says he has his patients to thank for in his nearly 30-year journey. To him, they’re someone’s father, wife, son or husband. Through their eager faces, he sees a family yearning for the health and the well-being of their loved one.

Inventing oral-ATO wasn’t the most difficult part. In the early 2000s, Hong Kong had virtually no ecosystem for medical innovation, neither the capital, infrastructure nor regulatory mechanism for drug registration. Kwong fought a lone battle, sustained only by his own time, as well as that of a few colleagues who offered to help out.

“Twenty years ago, not a single university in Hong Kong had a department designated for transferring scientific research into products,” Kwong laments.

Every step along the way, he had no precedent to follow. But his ambitions grew with his success. After developing the drug for his own patients, Kwong sought help from others beyond his hospital. To do so, he had to move beyond in-house preparation and properly register the drug. In the 2010s, after considerable efforts, he secured a local pharmaceutical factory with “Good Manufacturing Practice” certification. Prior to that, Hong Kong had virtually no experience in making prescription drugs, all of which had to be sourced from outside the city.

A greater hurdle followed — the Department of Health lacked the experience in registering a locally-developed drug as all medications had to be imported. Registration stalled until 2017, roughly two decades after the drug’s creation, when it was finally approved in the special administrative region. “If this were to be done on the mainland now, it would have been developed and registered in one or two years,” says Kwong.

Cross-border collaboration

The serendipity of arsenic trioxide also tied Kwong’s life trajectory in with the mainland’s medical development, set to take off. He had kept in touch with the mainland medical team and helped in the “go global” foray of some Chinese medical innovations. One of these efforts was the CAR-T cell therapy in March last year in which a lymphoma patient in Hong Kong received an injection of Shanghai-produced CAR-T cells as a personalized cancer treatment. It marked the first cross-boundary shipping of CAR-T cells and usage, signaling wider adoption of the mainland’s homegrown CAR-T cells for lymphoma patients in the SAR.

The therapy involves collecting T-cells from a patient and modifying them in a lab with a chimeric antigen receptor. After mass incubation in the laboratory, the cells are injected back into the patient.

The innovative immunotherapy has gained traction on the mainland with three CAR-T medicines now available for patients. T-cells from Hong Kong patients are harvested and shipped to Shanghai, and after the CAR-T medicines are produced, they have to be air-shipped under a temperature of -150 C back to Hong Kong and transfused into the patient within five days.

“The mainland’s medical development is advancing by leaps and bounds,” says Kwong, noting it has played a pivotal role in the international medical arena with a growing number of medical papers from the mainland being referred to at the highest level.

As Hong Kong’s largest hematology department, Kwong’s unit has set its sights on introducing new drugs from across the world, notably those from the mainland, with its rapid pharmaceutical discoveries in recent years.

The introduction of CAR-T cells was also made possible with a reformed drug registration mechanism that has been used in Hong Kong since November 2023. It marked the first advanced therapy product used under the new “1+” mechanism, and was one of 16 new drugs approved for registration in the city as of November last year.

The mechanism required only one reference drug regulatory authority, instead of two in the past, for drugs that are supported by local clinical data and recognized by local experts to be registered in the city.

The HKSAR government says it intends to set up its own regulatory body — the Hong Kong Centre for Medical Products Regulation — by the end of 2026 as part of wider efforts to establish primary evaluation.

In his 2025 Policy Address, Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu pledged to attract top-notch international and mainland pharmaceutical companies to operate in the SAR, and encourage pharmaceutical firms to leverage the city’s clinical trial platform to help bring innovative drugs to the mainland and international markets.

ALSO READ: Robotic stylist

Inspired by the mainland’s scientific findings, oral-ATO shows Hong Kong’s ability to transfer medical innovation into products and to act as a springboard for global expedition.

The drug is now being used clinically in the mainland cities of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area through the University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital. Research and clinical use of the drug have also been conducted in Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan.

With clinical trials on oral-ATO having started in the US and Europe, Kwong is optimistic it will get approval from the FDA in 2027.

The drug is credited as one of the first in Hong Kong to bridge the medical innovation gap between the mainland and overseas markets. For sure, it wouldn’t be the last.

As a doctor, Kwong’s top priority remains the welfare of his patients. “My greatest motivation as a doctor is to cure them. Without it, it would be meaningless.”

Contact the writer at stushadow@chinadailyhk.com