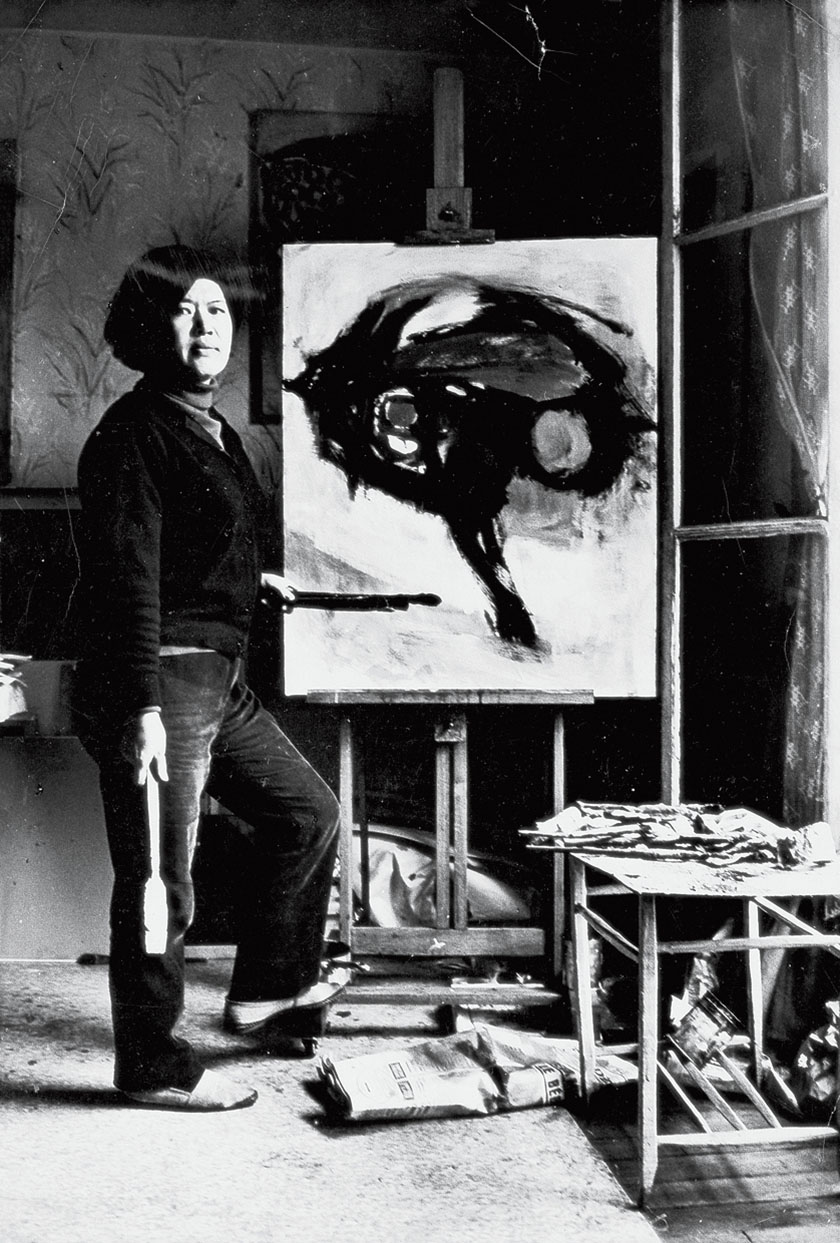

A retrospective of Hoo Mojong’s works at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center celebrates an outstanding though often-overlooked talent among fellow contemporary Chinese female artists. Rob Garratt reports.

‘We’d never heard of her, but this is just wonderful!” exclaims an antipodean tourist, wandering wide-eyed through the Objects of Play: Hoo Mojong Centennial Retrospective exhibition at the Chantal Miller Gallery of the Asia Society Hong Kong Center (ASHK). “Honestly, why don’t more people know about this artist?” his wife implores curator Valerie Wang, having successfully interrupted my private tour.

I have some sympathy with my interlopers. Strolling between the bright, bold, but quietly emotive canvases, I had the same question on my mind. Several art experts I approached admitted that they were not being familiar with Hoo’s work. Even art adviser Elaine Kwok, a key cultural voice in Hong Kong, says that she “discovered” Hoo only recently, through the exhibition.

READ MORE: Built on solid foundations

Yet Hoo (1924-2012) has been hailed as one of China’s most important female artists, a leading figure of global multimodernism who challenged the Eurocentric narrative pervading the art world in the 20th century. In Paris, she was awarded an exclusive work space neighboring Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti’s (1901-66) famous former studio. After returning to China in 1996, she was celebrated with four major retrospectives in Shanghai. Yet Hoo has never been the subject of an exhibition in Hong Kong, until ASHK, with support from the Bao Foundation, decided to feature her as the fifth artist of its Contemporary Chinese Female Artist Series. But her work remains far less known than that of her series predecessors, Pan Yu-lin (1895-1977) and Lalan (1921-95).

Independent spirit

Born in Ningbo in 1924, Hoo was nearly three decades Pan’s junior. Yet the two were friends, moving in the same art circles in ’70s Paris. “Pan was a kind of mentor, and she had advised Hoo: ‘If you want to be a professional artist in Paris, you are choosing a very difficult way,’” says Wang, going on to explain that “Hoo was not part of a popular movement,” and unlike Pan’s her work did not fit the “exotic, Eastern woman” stereotype.

Meanwhile, Lalan’s canvases have an “intricate, female, poetic kind of style”, which is at odds with Hoo’s defiant self-image. “Hoo’s is a much stronger personality than Lalan’s,” Wang says. “In her paintings, you can really feel the power of life itself.”

Yet Hoo’s relative obscurity may have as much to do with her personality, stubbornly shunning self-promotion. Wang says that while “Pan was extremely sociable, Hoo was very quiet — she won’t share her story, her family and her love affairs — and I think this is one of the biggest reasons Pan is so much better known.”

While Hoo was notoriously private, it is known that she did not have a happy marriage. In the ’40s, she was forced to flee Shanghai for Taiwan because of her husband’s political views, and yet after giving birth to two children, the couple separated. There might be a reference to her isolation in Two Coats, showing the items of clothing left behind by their owners in a hallway. In an apparent self-portrait, called Contemplating, a mournful figure, lit by a solitary light bulb, clutches a volume bearing the name “Mojong”, suggesting a figure locked in a loop of introspection. “Her life was really tough, so what you see on the canvas is her life,” Wang says.

Global citizen

Hoo was over 40 when she arrived in Paris in 1965, at a thrilling but tumultuous time in the global art world that gave birth to a quick succession of cultishly competitive artistic revolutions, including Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and Minimalism. Yet Hoo was not one to follow trends. Daphne King, global director of Alisan Fine Arts gallery, notes that Hoo neither embraced the Tachisme style of abstract painting like her Beijing-born contemporary Zao Wou-ki (1920-2013); nor followed the classic Chinese tradition of social realism inherited by fellow Ningbo native Chen Yifei (1946-2005).

She turned down an invitation to study at the famed Beaux-Arts de Paris — where Pan had trained — instead attending the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, following compatriots Zao, Pang Xunqin (1906-85) and Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), as well as Western luminaries Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) and Giacometti. After winning the first prize at the Salon des Femmes Peintres in 1968 for her Toy Series, the institute offered Hoo the historic studio where she spent much of her 37 years in Paris. “During a period dominated by male artists, it was challenging for women artists to distinguish themselves,” King says. “However, Hoo managed to stand out.”

While Hoo refused to follow trends, she was still paying attention. King notes the way the artist “blends European art styles with her unique creative language”.

Her bold use of perspective owes a certain debt to Surrealism, evident in the huge bananas dwarfing the hands that hold them in Figure Series 30.

Wang sees Fauvism in Hoo’s use of color, and the emotional depth of German Expressionism in her powerful nude sketches. Rather than the submissive and sexualized male-authored nudes we’re most familiar with, Hoo’s female figures are bold, strong and often looking out from the canvas, antagonizing the objectifying male gaze.

Homecoming

While Pan lent into her Chinese heritage, arguably exoticizing the East for a Western audience, and Lalan’s work bore traces of classical Chinese ink landscapes, in Hoo’s art, one has to look harder for influences of her homeland. Rather, the bold lines and warm, earthy tones that dominate so many of Hoo’s canvases can be traced to the years she had lived in Brazil and Spain.

Wang sees the influence of Taoism in the stillness and simplicity in Hoo’s work. She contends that the stark simplicity of Hoo’s still-life paintings is owed to an elemental Oriental sense of space rather than American Minimalism, which was popular at the time. A closer inspection of Toy Series 11 reveals a traditional Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) chair.

Notably, the greatest stylistic shift in Hoo’s art came after she visited China for the first time in more than four decades in 1996, at the age of 72. The occasion was the first of three major retrospectives of her works staged at the Shanghai Art Museum. Buoyed by the embrace, she moved to the city in 2002, and would go on to donate more than 100 pieces to the institution.

Following her return to China, Hoo’s works became bolder, brighter and physically larger. Her nudes from the era reflect a new dynamism somewhat reminiscent of Cezanne, while the Plant Series documents the bucolic garden of her Shanghai home — the artist’s first time depicting a Chinese scene on canvas.

ALSO READ: The business of public art

Ultimately, it’s the honesty of Hoo’s everyday scenes that makes them so powerful, and sets her apart from peers like Pan and Lalan. “Hoo is actually the one that went over and above cultural differences,” Wang says, going so far as to compare the artist with Impressionist legends Van Gogh (1853-90) and Renoir (1841-1919) — “the masters devoted to the object itself, the landscape itself, to life itself”. “Like them, Hoo is just naturally pouring herself into her art.

“You can feel that same spiritual power in her work.”

If you go

Objects of Play: Hoo Mojong Centennial Retrospective

Dates: Through Aug 17

Venue: Chantal Miller Gallery, Asia Society Hong Kong Center, 9 Justice Drive, Admiralty

https://asiasociety.org/hong-kong/exhibitions