A new exhibition at Tai Kwun highlights what Chinese artists make of the digital revolution and growth of AI and how, for many of them, new technologies have shaped and altered their practice. Chitralekha Basu reports.

A mammoth robotic arm, swivels on its axis — trying to sweep away the dirty red liquid spreading across the white floor. It’s a futile endeavor. The machine keeps trying, nevertheless — swooping down on recalcitrant trails of liquid. It behaves like a caged beast, triggered, as if, by the presence of visitors looking on from outside the transparent acrylic walls. In reality though, the movements are programmed and the control panel is displayed on a desktop screen, next to the installation.

Can’t Help Myself (2016-19) by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu is easily the most visually compelling object in Stay Connected: Navigating the Cloud, which opened on Sept 24 at Tai Kwun. Featuring more than 50 works by 35 artists and art collectives, the show looks closely at what Chinese artists make of the digital revolution and the wide use of the internet in China since 2008. The artworks also reflect how the availability of advanced technologies has created new modes of art, sometimes profoundly altering an artist’s practice — by providing tools, subject and inspiration.

READ MORE: Different strokes

Similar to Can’t Help Myself, which invests a basic robotic arm movement with the kind of drama and emotion that feels almost human, there are a few other instances of artists inviting viewers to consider technology, and its tools, as works of art, in and of themselves. For instance, Phoebe Hui’s series of drawings — produced by robots trained on open-source images from NASA as well as 17th-century engravings — are an attempt to visualize the side of the moon that remains hidden to us. The exhibition displays the drawings alongside a demonstration of how they are produced.

Guan Xiao’s three-channel video Cognitive Space (2013) displays hundreds of random images in the shape of digital file icons, for a split second each, alluding to the sensory overload experienced in the digital realm. Guo Cheng’s installation, The Weather Consensus (2022-25), reads varying weather data on the same city released by three different sources, to create a computational competition, with the “winner” preserved on the blockchain and displayed on a vertical digital screen.

“It’s shaped like an antenna tower and combines blockchain technology with traditional neon lighting,” says exhibition co-curator Kwok Ying, drawing attention to the juxtaposition of old and new technologies in The Weather Consensus. The data is also reflected in playful neon sculptures of cloud, rain and the sun — which light up to indicate the weather situation in real time — “adding a warm human touch to a heavy concept”.

The piece calls into question blockchain’s USP as a site for storing data that remains secure and incorruptible for all eternity, underscoring the fact that the data in question may not be an accurate reflection of the truth.

Keeping in touch

Stay Connected: Navigating the Cloud is informed by the hope for finding positivity and meaningful connections at a time of uncertainty and growing cynicism — to which the internet contributes in no small measure.

“The internet can be an instrument for spreading the message of solidarity, just as it can isolate people,” says co-curator and head of art at Tai Kwun, Li Pi. “When people take leave of each other, they often say, let’s keep in touch though we may not be seeing each other in person. And that really is our hope for such a divided world.”

He states that though the show features Chinese artists — some of whom are based overseas — its focus is on how “these artists reflect contemporary reality, and the human condition, not only in China but also the world over”.

Li Shuang’s 2015 photo showing her walking around in New York’s Times Square on a snowy Valentine’s Day, wearing a huge sign on her back that says, “Marry Me for Chinese Citizenship”, is a case in point. In it, Li turns a not-uncommon prejudice held against single Chinese women immigrants in the US — that they date American men with an eye on securing American citizenship — on its head.

While social media can start, spread and perpetuate xenophobia, it can also help people find empathy and community. Chen Zhe’s twin series of images, The Bearable (2007-10) and Bees (2010-12), tells the story of how the artist found an online support group after she started posting pictures of the scars she had inflicted on herself.

The connectedness inherent, though not always apparent, in human society is the theme of Zhang Yibei’s romantic bijou sculptures collectively titled, Limpid, Golden, Calling (2025). Bronze saplings bearing leaves, fruits and occasionally snails rise from the floor in one. Not too far away, an army of taps display biomorphic features, bringing to mind stalks weighted down by flowers, which, in this case, have to be imagined.

Li explains that the piece is inspired by some of the vital things shared between neighbors who often remain oblivious to such connections. “While people are connected through the internet, they can also be connected through infrastructure — air vents, water pipes and cables. Zhang breathes life into these connections,” says Li.

Influential algorithms

The internet has introduced words, images and concepts that did not exist before. Shao Chun’s installation Inner Beads (2025), for instance, is informed by her research into the traces of internet ghosts left behind on social media. Paradoxically, the shape of this elaborate, intricately detailed and yet extremely spare piece gains substance only when viewed together with the shadows it casts on the floor. Using fishing wire, beads, tiny bells, silicone fabric, synthetic hair, eyelashes, wasted cosmetics and a lab flask, Shao has “composed an abstract ‘image’ of a scattered and/or absent body” that throbs with vitality, goading viewers into imagining the missing bits.

Payne Zhu’s video installation Reverse-rendering (2022) invites viewers to reflect on user behavior, consumption patterns and the fragmented nature of online experiences. It shows a continuous stream of images scrolling upwards. When the speed of scrolling “surpasses the processing speed of digital imaging, the visuals begin to glitch”.

Also underscoring how social media algorithms influence consumer behavior is Li Hanwei’s Sneeze (2023/2025) — a physical reconstruction of an internet clip showing a car crashing into a public toilet that went viral.

Nostalgia for old tech

Both Lam Pok-yin’s multi-channel video installation, An Increasingly Difficult and Futile Task (2021), and Wong Ping’s video film, Dear, Can I Give You a Hand? (2018), look back with love and longing on the old technologies that have fallen by the wayside as we race to develop and adapt to newer gizmos. Lam puts a series of outdated mobile phones under bell jars — awarding them the dignity akin to precious objects in a museum collection. The phones continuously ask viewers to verify if they are human — the irony being that the footages, playing on a loop, is sourced from an American e-commerce company that employs humans to conduct the data identification and processing, as their wages cost less than machines.

Wong’s film illustrates how today, the generation gap is also about the difference between the digitally enabled and the rest. Using his unique visual language — lurid colors, suggestive imagery and human figures reduced to simplified geometrical forms such as cylinders and circles — Wong tells the story of an old man who longs for VHS cassettes. After his digital grave is consigned to cloud storage, his son forgets the password, leaving him in eternal solitude.

Art in the age of AI

Li Yi-fan’s video film What is your Favorite Primitive? (2023) shares Wong’s morbid humor in its speculations about a tech-dominated future. Using game-engine and motion-capture technologies, Li responds to the growth of generative AI by creating a constellation of avatars, modeled after himself, who mock and threaten the extinction of the human race.

Lawrence Lek’s video installation Empty Rider (2024), transports viewers to an apparently empty courtroom where an automated car is on trial for attempting to murder the CEO of the company that created it. Presided over by an AI judge, the live-streamed proceeding — during which the car, the corporation and the “therapist” who trained the self-driving algorithm try to manipulate the truth — makes viewers wonder about the possibility of not just machines thinking for themselves but also influencing the thoughts of others.

Vvzela Kook’s rainbow-colored neon sculpture is part of an installation that also includes a 3D-printed sculpture done in Christmassy red and green — a fantastical rendition of the now extinct Kowloon Walled City, which the artist imagines as humanity’s “final stronghold in its resistance against AI”.

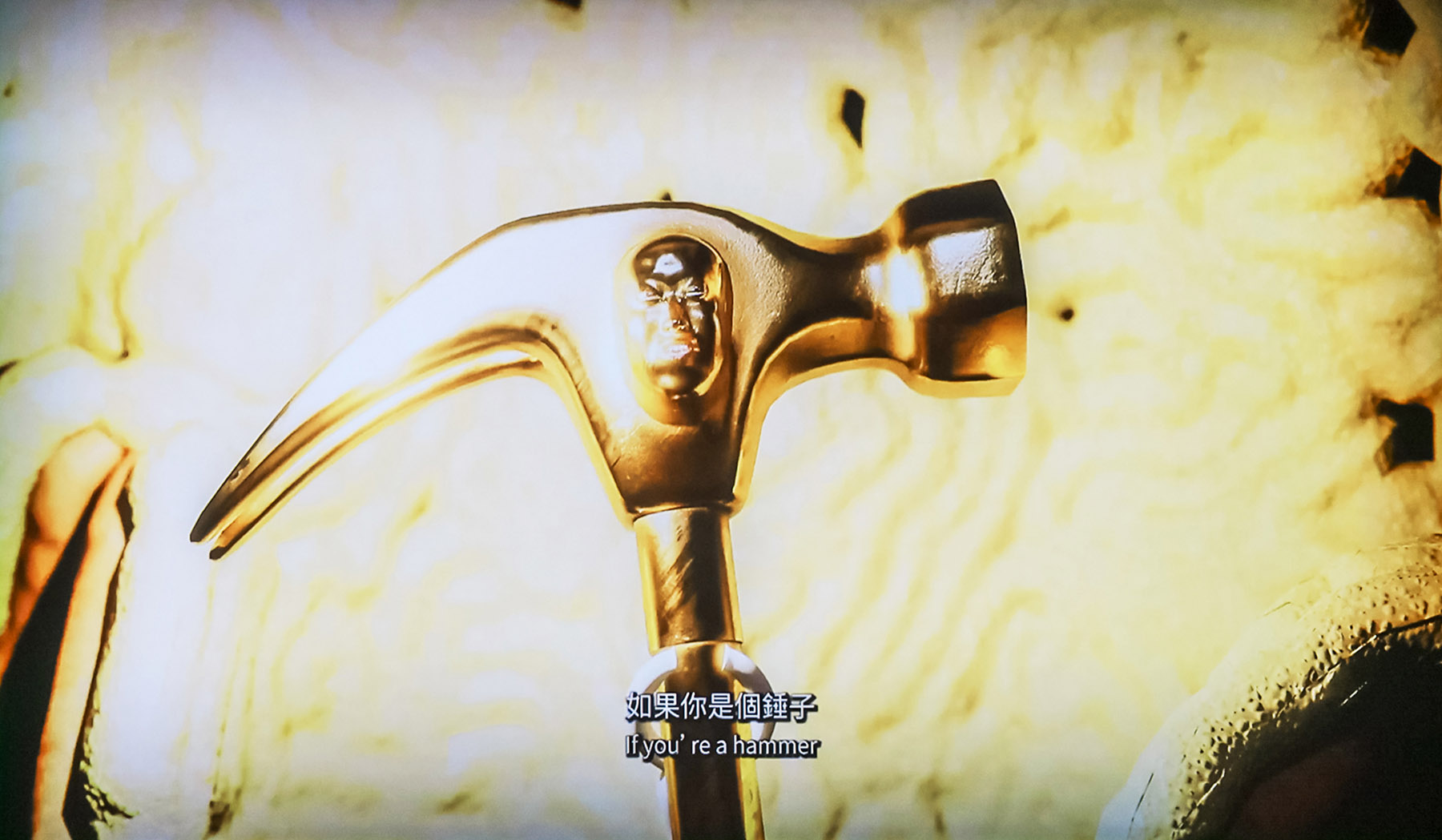

Framed like a karaoke-style video lecture, Wong Kit-yi’s Robot Take Me Home (2023) imagines an automated future where human hands have lost their purpose. The piece invites viewers to wonder about certain core elements of the human experience that we stand to lose as a result of technological advancement.

ALSO READ: Artful dodgers

“What makes us humans different from other animals is that we can use our hands to make things,” says co-curator Li. “Wong’s piece asks if automated cars make human hands redundant, how are we going to redefine their purpose?”

If you go

Stay Connected: Navigating the Cloud

Dates: Through Jan 4

Venue: JC Contemporary, Tai Kwun, 10 Hollywood Road, Central

www.taikwun.hk