Songs and classic Chinese poetry and painting inspire a renowned former teacher's comics, giving visitors to an exhibition in his honor an opportunity to peek inside his mind, Lin Qi reports.

On the second-floor gallery at the Art Museum of the Beijing Fine Art Academy, the usual quietness occasionally interrupted by visitors' murmuring opinions is replaced by singing these days, which lights up the room as visitors stroll between paintings.

The Last Rose of Summer, a soothing piece inspired by the namesake poem of Irish poet Thomas Moore, is played in rotation.

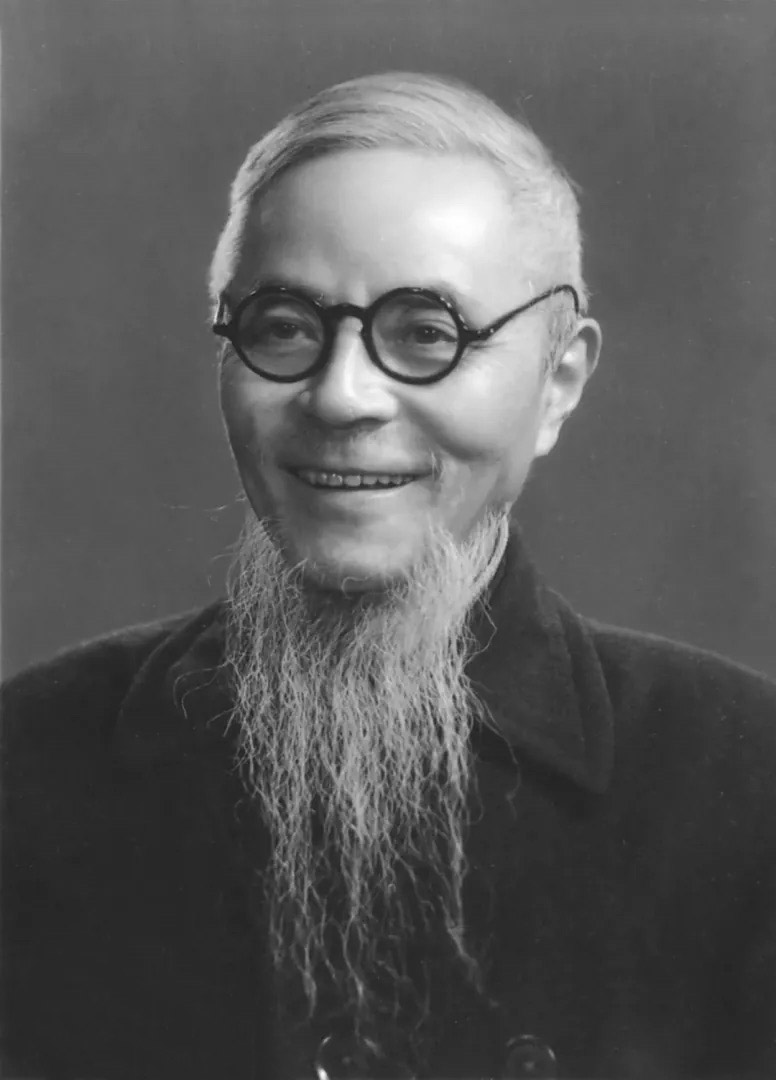

Several decades ago, at a Shanghai middle school, the same melody tugged at the heartstrings of students attending a music class led by Feng Zikai (1898-1975).He later recollected how much students loved to learn lyrics and scores in his class and were touched by well-known songs, such as The Last Rose of Summer, Home Sweet Home, How Can I Leave Thee, and others that he taught.

READ MORE: Virtuoso's donated works carry on artistic lineage

"When the tunes ended," Feng later recalled, "the classroom fell into silence, and the children still buried their heads in the scores — it seemed as if everybody had been lost in a dream".

"I couldn't help, deep in my heart, marveling at the unbelievably infectious appeal of music."

The Last Rose of Summer was significant to him for a long time. In 1971, he wrote the song's score and the original English verses, and translated the lyrics into Chinese in the style of classic seven-character poetry.

When people hear the song at the Art Museum of the Beijing Fine Art Academy, they can also sing along to Feng's translated version as his handwritten sheet is on display in the ongoing exhibition, Endless Refreshment.

Running through to Oct 12, the exhibition marks the 50th anniversary of Feng's passing. It is also a gift presented jointly by the Beijing Fine Art Academy and the Feng Zikai Research Association, founded by Feng's family members in Shanghai. As the exhibition's theme suggests, its creativity and human touch aim at bringing people a refreshing respite as summer comes to an end.

The works on show, together with photos, letters, and historic documents, are primarily from the collections of the Beijing Fine Art Academy and the Feng family.

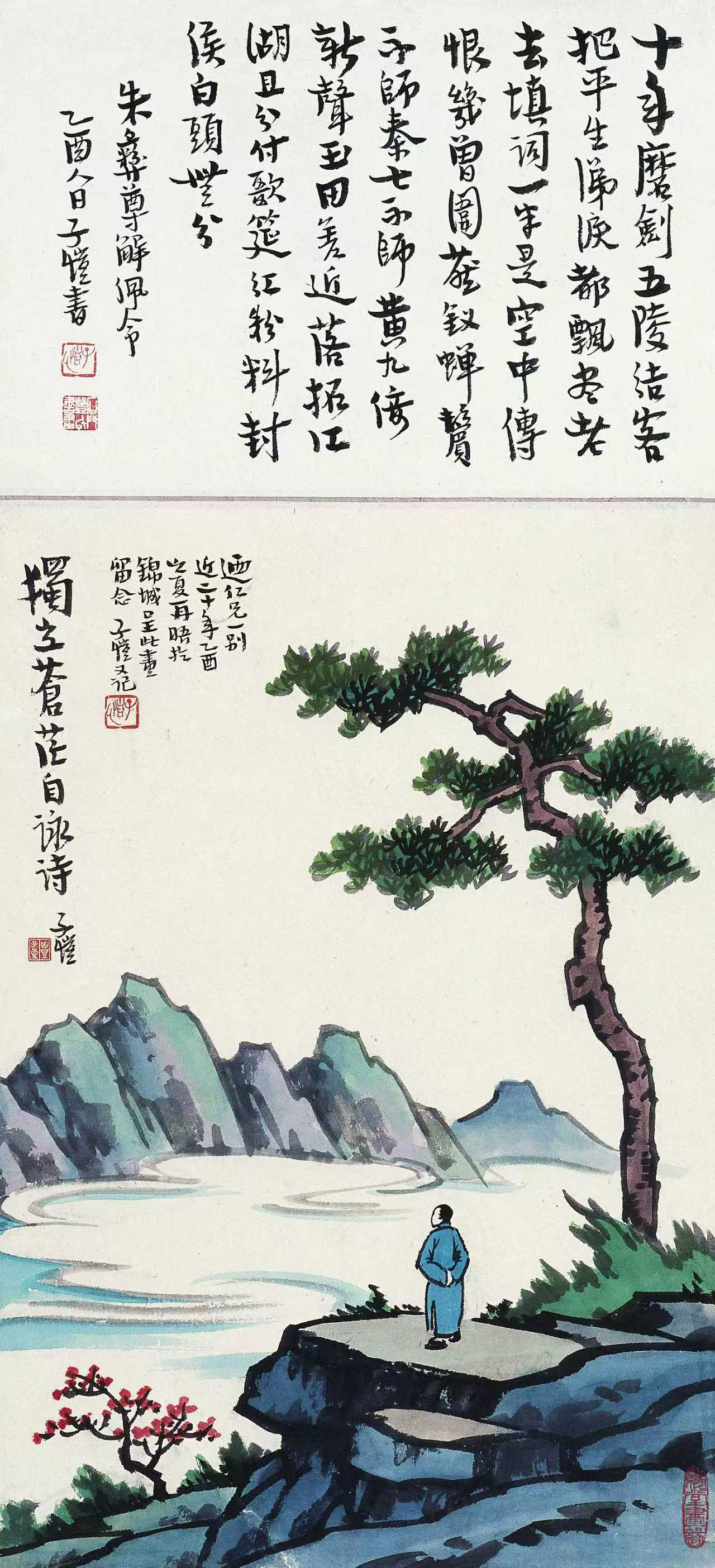

Among the figures of prominence who illuminated the landscape of 20th-century Chinese art, Feng was a reformer who was dedicated to the creation and education of fine arts and music, as well as writing and publishing. He was also a widely beloved artist whose paintings integrated a comic style, which evoked a profound resonance among his audiences spanning generations and various educational backgrounds.

Hailing from East China's Zhejiang province, Feng received formal training to be a teacher. He once studied arts and music in Japan for nearly a year. Returning home, he taught, created art, translated, and wrote.

Yi E, a senior researcher at the National Art Museum of China and the exhibition's chief curator, says Feng is not only a trailblazer of modern Chinese comic art, but also an outstanding representative who ushered in the transformation of classic Chinese painting in the 20th century by combining the two forms.

"He inherited the xieyi (sketching the spirit) tradition of Chinese painting and blended it with the simplified sketching approach of comic art to depict people's daily lives," she says.

Yi says his unique style conveys a light mood with underlying messages, which make Feng a household name and his works loved by generations of Chinese people today. While his artworks make people smile and feel delighted, they also make them think.

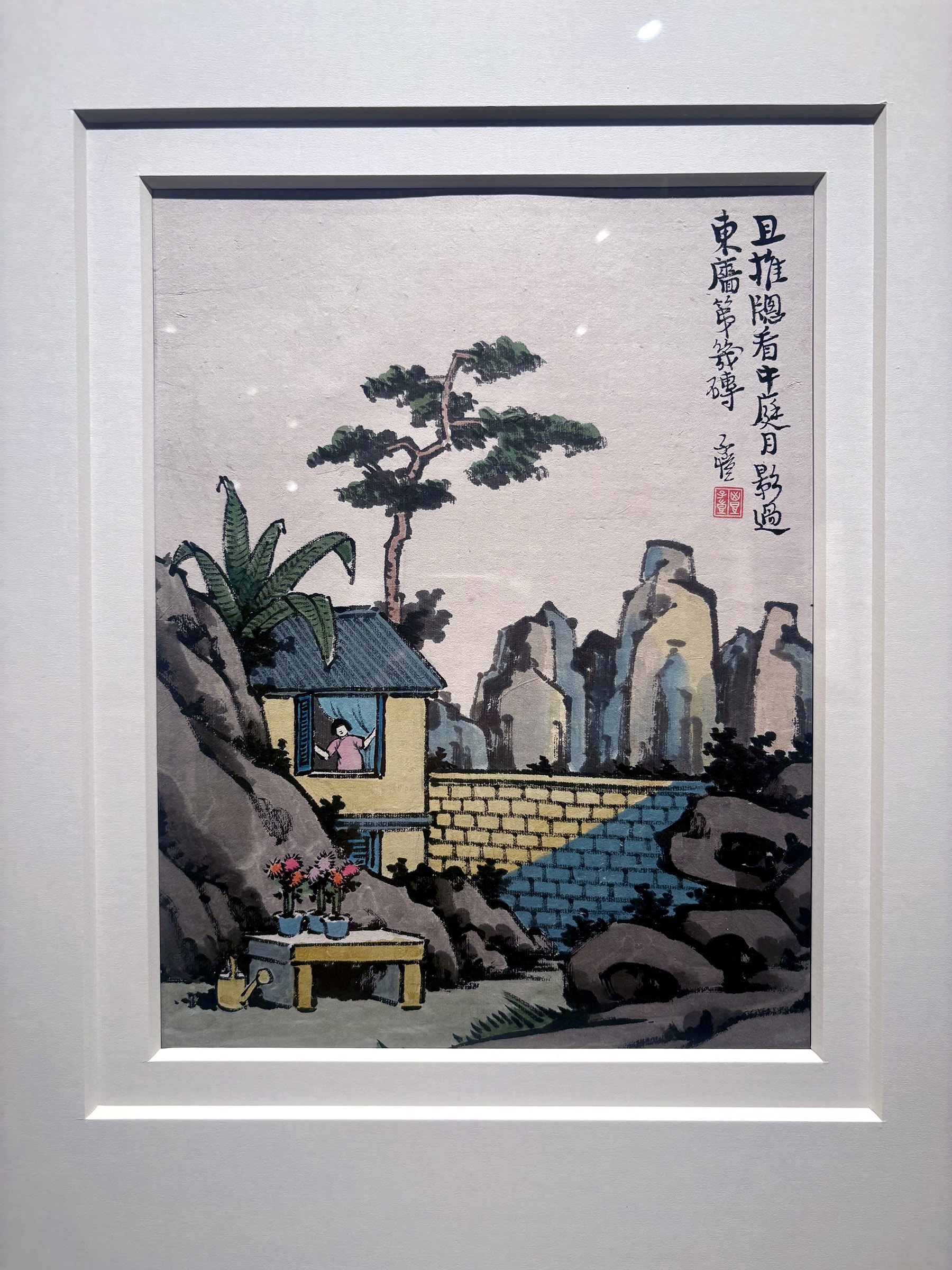

In Moonscape in the Courtyard, a work on display, Feng didn't draw the moon directly, but he accentuated the tranquility of the mood with a scene in which the house, wall, mountains and flower pots on a bench in the courtyard are illuminated by moonlight.

Yi adds that the poetic sentiments, sense of humor, and thoughtful reflections embedded in his art continue to inform people's understanding of Feng.

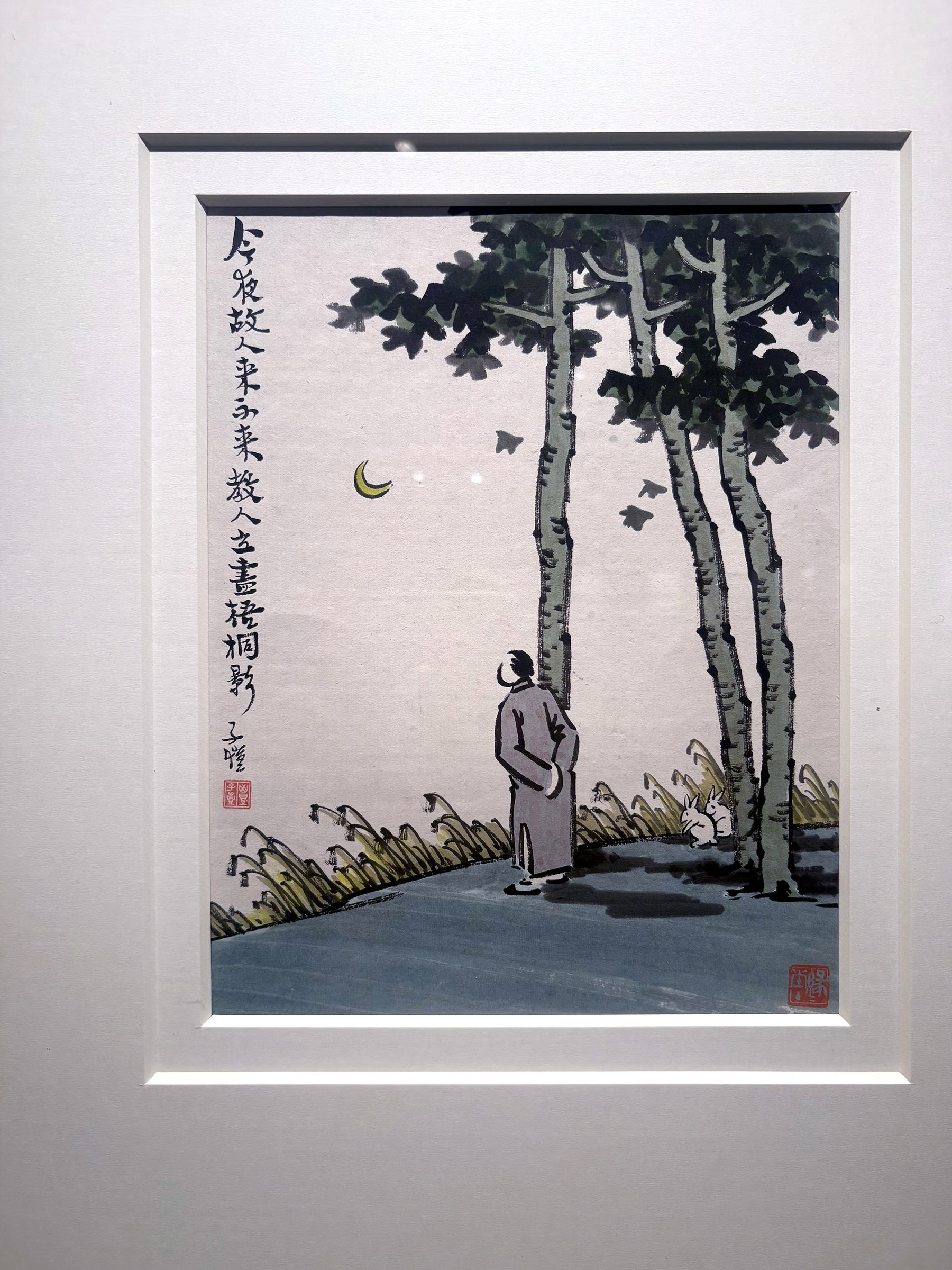

Feng was also enthusiastic about classic Chinese poems. He injected the rhetorical beauty of these verses into his artistic creations to reflect the life and mentality of the people in his time.

"He drew these daily scenes not because he was touched and wanted to document them; his insightful views of society, nature, and all living things inspired people to think," Yi says.

Some of the paintings on show are from Feng's best-known collection, Husheng Huaji (Painting Albums for the Protection of Life), which was initiated by his schoolteacher, Li Shutong, who later converted to Buddhism and was also known as Master Hongyi (1880-1942). The two collaborated on the first two albums.

After Li died, Feng continued the project until he also passed away, leaving six albums in which several hundred drawings express compassion and benevolence for all life and a wish for peace.

He worked on them even when he became a refugee during the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45). He painted to celebrate the victory of the War of Resistance. A painting on display, dated 1945 and titled Used Shell as a Vase, depicts lotus flowers in a used bomb shell and two smiling figurine toys.

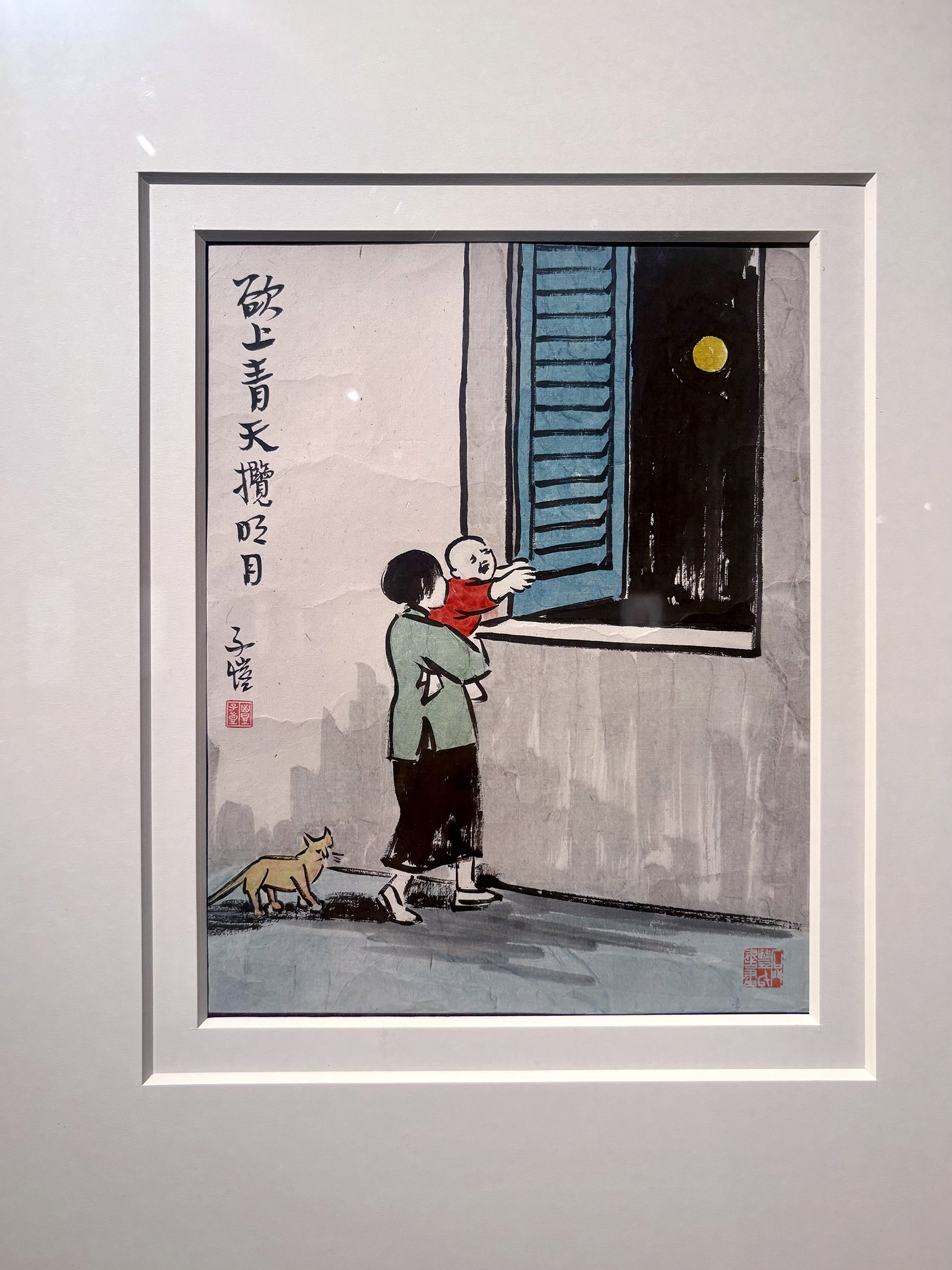

Another popular theme in Feng's oeuvre, as a devoted father, is children. He painted them dressing up in their parents' clothes and shoes for fun, asking for the full moon in the night, and fighting and destroying things at home, ruining the adults' Sunday peace.

Feng once said: "Recently, my mind has been preoccupied by four things — the deities, the stars in the universe, the arts, and children in the human world."

In an article, About My Paintings, he wrote that he was jealous of children's innocent attitudes and envied the breadth of their world.

Wu Yunhong, also a curator of the exhibition, says that many of the artworks exhibit Feng's shrewd observations of children's behaviors and minds, and that he always valued childlike innocence and sincerity, family love, and friendship.

ALSO READ: Drawing the line on a promise kept

Feng's letters to his sons and daughters are also on show.

Wu says: "He was not only a noted educator and artist. Moreover, he was a father who showed wisdom, care and love toward his children."

Wu Hongliang, director of the Beijing Fine Art Academy, says people see themselves in Feng and the figures in his work. "In the world of Feng, people picture themselves in it — vulnerable, quiet, cozy, and enjoying peace in the corner; and they feel their hearts, big and caring for the whole world, embracing warmth and daring to face injustice."

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn