Chinese diplomat in Austria Ho Feng Shan saved thousands of refugees fleeing Nazi terror during WWII by issuing visas for life, Ho Manli reports.

Toward the end of 1938, in the second year of the full-scale Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), and on the eve of World War II in Europe, there was suddenly a mass influx of European Jewish refugees into the Chinese port city of Shanghai.

In less than two years, some 18,000 Jews would seek refuge in Shanghai. During that period, the very use of its name as a destination provided thousands with a means of escape from certain death at the hands of the Nazis.

How did an occupied war-torn Chinese port city become a refuge of last resort from the Holocaust?

READ MORE: Exhibit chronicles doctor's dedication to China

It has only been in the last two decades that this history has surfaced and become more widely known. At that time, elderly Jewish Shanghai survivors began to write their memoirs, and I embarked on a two-decade long investigation into the instrumental role that my late father, the Chinese diplomat Dr Ho Feng Shan (1901-97), played in saving Jews.

Well before Nazi policy turned to genocide in 1941, the Anschluss, the political union of Austria and Germany in March 1938, unleashed a reign of terror on Jews, precipitating a refugee crisis.

Up until then, Nazi efforts to render Germany Judenrein, or "cleansed of Jews", had not gained much traction. But with the Anschluss, anti-Semitic violence and persecution of Jews escalated exponentially.

The Nazis created draconian bureaucratic measures for Jewish emigration combining economic expropriation and forced deportation, a "model" perfected in 1938 in Vienna by Adolf Eichmann, who later became one of the architects of "the Final Solution", the Nazi plan for the genocide of Jews in 1942. This "model" was subsequently instituted in all Nazi-occupied territories.

My father was posted to the Chinese legation in Vienna in 1937. He watched in horror as Adolf Hitler marched triumphantly into Vienna in March 1938, to a delirious welcome by the Austrians.

"Since the Anschluss, the persecution of the Jews by Hitler's 'devils' became increasingly fierce. The fate of Austrian Jews was tragic, persecution a daily occurrence," my father wrote in his memoir Forty Years of My Diplomatic Life.

After the Anschluss, all foreign diplomatic missions in Vienna were downgraded to consulates. My father was appointed Consul General a month later.

Around the same time, the first Austrian Jews were sent to Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. They were told by Nazi authorities that if they produced "proof of emigration" to another country, they would be released. Many Jews wanted to emigrate to the United States, but the US not only required an affidavit of financial sponsorship but had long ago filled its Austrian quota. Those who wished to go to Palestine found that Britain, under pressure from the Arabs, had severely reduced the quota for Jewish emigrants.

Jews besieged foreign consulates in Vienna day after day. Obtaining the "proof of emigration" required by Nazi authorities became a desperate and agonizing quest for survival. Here is how one refugee described it:

"Visas! We began to live visas day and night. When we were awake, we were obsessed by visas. We talked about them all the time. Exit visas. Transit visas. Entrance visas. Where could we go? During the day, we tried to get the proper documents, approvals, stamps. At night, in bed, we tossed about and dreamed about long lines, officials, visas. Visas."

At this time, foreign diplomats like my father could play a crucial role in helping Jews, but none did so. Many of their countries, and nearly all of the 32 Western nations participating in the Evian Conference in July 1938, had anti-immigration policies and were unwilling to open their doors to Jewish refugees.

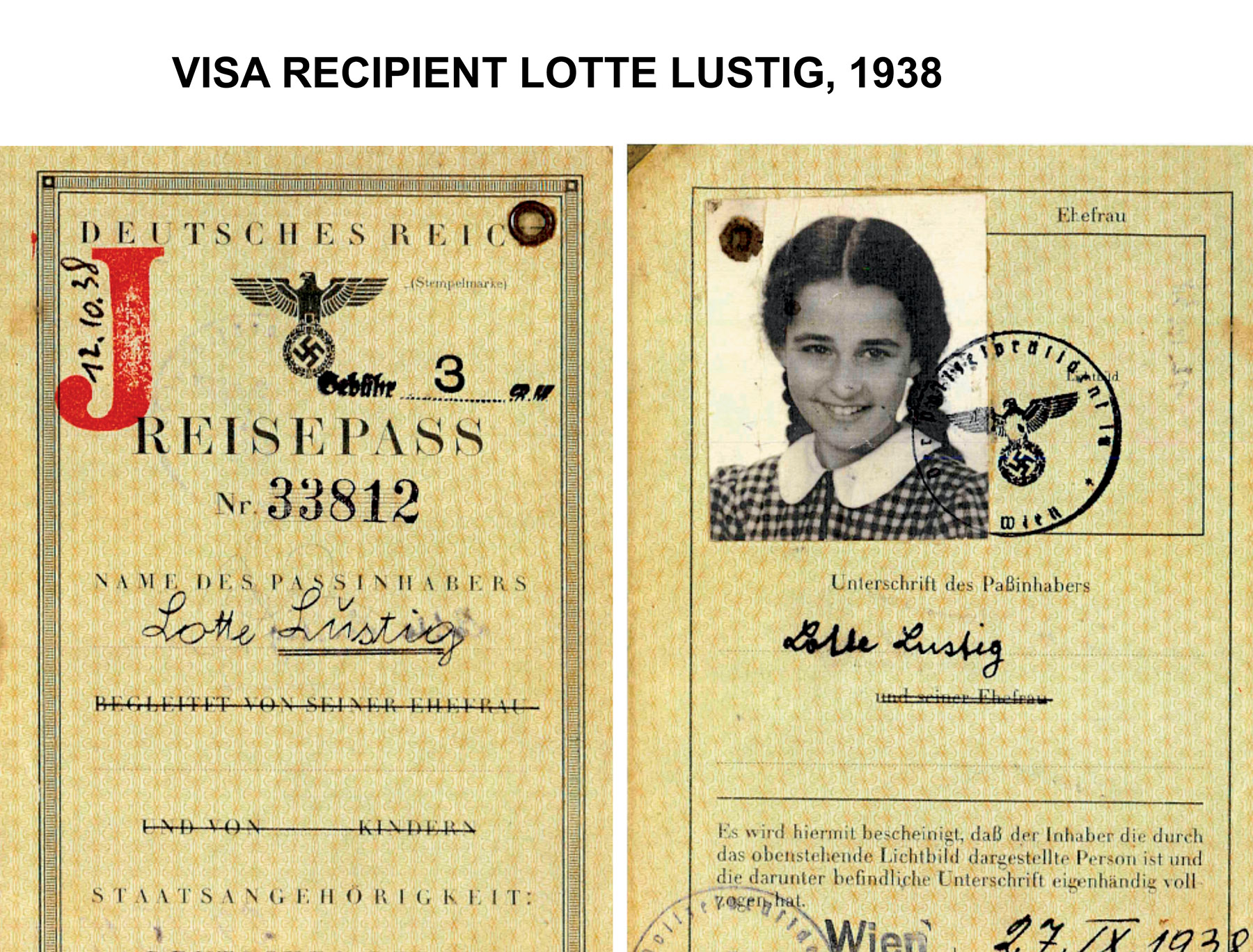

The father of 11-year-old Lotte Lustig, for example, obtained an American telephone directory, and Lotte wrote to all the people who bore the same last name — Lustig — asking them to sponsor her family to the US.None agreed. The Lustigs obtained Shanghai visas from my father's consulate on Oct 18, 1938, a day when at least 106 such visas were issued, and escaped to Shanghai.

My father came from a generation of Chinese who keenly felt the 100 years of humiliation that China had suffered under foreign imperialism, so he could not stand idly by. "Seeing the tragic plight of the Jews, it is only natural to feel deep compassion, and from a humanitarian standpoint, to be impelled to help them," he would later recall.

"I used every means possible, saving who-knows-how-many Jews!"

However, unlike his diplomatic peers, my father faced some daunting obstacles as China's representative in 1938. The first was access to his home country, much of which, including all of its ports of entry, had been under Japanese occupation since 1937. Any entry visa issued by a Chinese diplomat would certainly not be recognized by the Japanese occupiers.

There was, however, one loophole: the port of Shanghai. Following the Opium War of 1840, portions of Shanghai had been carved up by the foreign imperialist powers into extraterritorial "concessions". The Japanese invasion in 1937 occupied the Chinese portions of the city, but the International Settlement and the French Concession remained untouched enclaves.

Until July 1937, the Chinese Nationalist government had exercised passport control for entry into Shanghai, but after their retreat to the wartime capital of Chongqing, the harbor was left unattended. Because the other foreign powers in Shanghai did not want to be "inconvenienced", it was the only entry point into China that the Japanese occupiers did not exert control over. Until the end of 1941, when the Japanese took over the entire city, there was no harbor authority to examine passports or entry documents into Shanghai. Anyone could land ashore without passports or papers.

My father took full advantage of this situation and devised an ingenious strategy: issuing entry visas to Shanghai, a destination requiring no visa for entry.

This intentional off-label use of a standard entry visa would provide the "proof of emigration "required by Nazi authorities to allow safe passage out of Nazi-occupied territories and to be released from detention. The visas could also be used to obtain transit visas into otherwise inaccessible countries on the pretext of going to Shanghai. Many Shanghai visa recipients in fact did not go to Shanghai but used these visas to make their way to the Philippines, Cuba, Palestine, England and even the US, the only places they could get to.

At the time, China, and especially Shanghai, was alien to most Europeans. Soon after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, a handful of German Jewish doctors and dentists had answered an advertisement from the foreign concessions for medical professionals and had set up practices in Shanghai. In the subsequent five years, there were no further arrivals until the mass influx of Jewish refugees landing in Shanghai at the end of 1938, after the Anschluss and then Kristallnacht, the Nazi-orchestrated anti-Jewish rampage known as the Night of Broken Glass on Nov 9 and 10 of that year.

Four months after the Anschluss, 17-year-old Eric Goldstaub made the rounds of 50 consulates in Vienna before obtaining 20 visas for himself and his extended family from the Chinese Consulate General. The visas were to a destination — Shanghai — that he had never heard of, in a distant country — China — that he had never dreamed of going to, Eric later recalled.

With the visas, the family bought tickets on an Italian luxury liner from the Lloyd Triestino company, which was war profiteering by ferrying Jewish refugees to Shanghai.

But before they could leave, Eric and his father were arrested on Kristallnacht, along with 30,000 Jewish males from Germany and Austria. Because they were able to produce the Shanghai visas as proof of emigration, they were released and set sail for Shanghai in December. On board the ship, Eric took photographs of fellow Jewish refugee passengers.

More importantly, in 1938 and 1939, the Shanghai visas were instrumental in securing the release of those deported to concentration camps, especially after Kristallnacht. Austrian physician Jakob Rosenfeld was among those deported to Dachau and then to Buchenwald. He was released in 1939 and went to China, where he joined the Chinese New Fourth Army as a medical officer and participated in the revolution.

By making Shanghai a final destination, my father also provided a safety net to Jewish refugees who were unable to obtain his Shanghai visas in Vienna. After the Anschluss and Kristallnacht, word spread rapidly throughout Nazi-occupied territories that in China there existed a port which required no entry papers. This prompted a mass exodus by ship, and later by rail, to Shanghai between 1938 and 1940.

As Evelyn Pike Rubin, a survivor, wrote in 2007: "I am from Breslau (today's Wroclaw, Poland), and all I can remember is that my parents seem to have heard about Shanghai from the Austrian Jews who needed to leave right after the Anschluss. I guess someone in Austria heard about Shanghai being an 'open city' and the word spread and also got to us in Germany."

The majority of the 18,000 Jewish refugees who ended up in Shanghai were from Germany. Only 5,000-6,000 were from Austria. Most of the Austrian Jews who were able to obtain visas from my father's consulate used them as a means to escape elsewhere. The last group of refugees were 300-400 Polish Jews, the entire Mir Yeshiva (a traditional Jewish religious educational institution), who had fled to Kobe, Japan, but were deported by the Japanese to Shanghai in 1941.

The second major obstacle my father faced was from his home government. The Nationalist government had had long-standing economic and diplomatic relations with Germany. But by 1938, Hitler had begun to turn to Germany's soon-to-be ally, Japan. Desperate to salvage deteriorating diplomatic relations with Germany, Chen Chieh, the new Chinese ambassador to Berlin, ordered my father to desist from issuing visas to Jews. My father disobeyed.

On April 8, 1939, roughly a year after he began issuing visas, my father was punished with a demerit for disobeying orders. Just prior to that, the consulate building at 3 Beethoven Platz was confiscated by the Nazis. The Nationalist government not only did not protest this breach of diplomatic extraterritoriality but refused to give my father funds to relocate. My father moved the consulate to much smaller quarters around the corner at 22 Johannesgasse and paid all the expenses himself. In February 1940, he was removed from his post and transferred out of Vienna.

ALSO READ: A musical celebration of compassion

The Jews who arrived in Shanghai faced harsh and brutal wartime conditions under Japanese occupation, but survived. None were ever reunited with my father. Until now, most did not even know his name, as my father never sought recognition for his deeds.

This unusual chapter in history serves as a reminder that there is an indelible and direct link between East and West in humanity's shared struggles.

On this 80th anniversary year of victory over fascism, my father's humanitarian deeds can best be remembered not for whom he saved, but simply that they were human lives.

Lao Tzu said: "The sage saves others and abandons none."

Ho Manli, daughter of Ho Feng Shan, did not follow in her father's diplomatic footsteps and instead chose journalism. In 1981, she was one of the foreign editors who worked at China Daily on its launch, and also at China Daily US edition on its launch. For the past two decades, she has been uncovering and documenting the history of her father's wartime heroism and is working on a book.

Contact the writer at homanli@chinadaily.com.cn