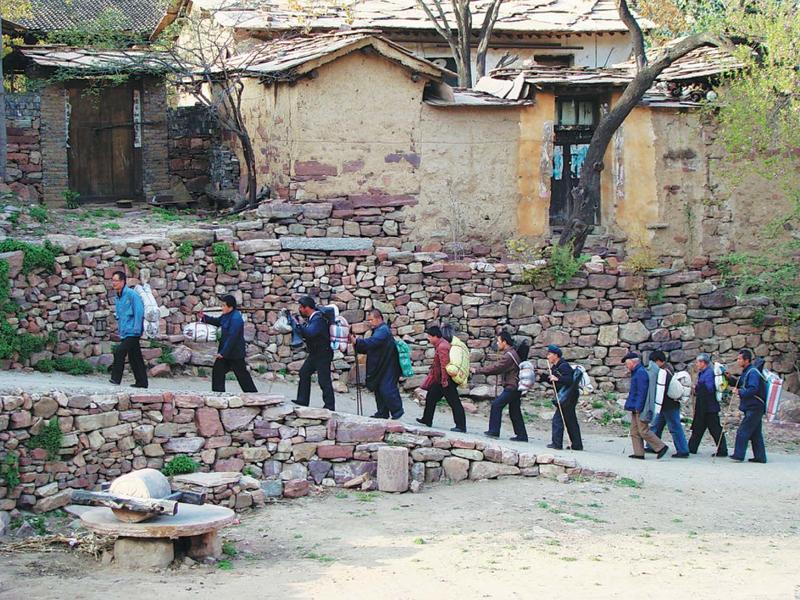

This undated photo shows members of the Zuoquan Blind Men’s Publicity

Team. The team has been traveling from village

to village to perform for locals for 80

years. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

This undated photo shows members of the Zuoquan Blind Men’s Publicity

Team. The team has been traveling from village

to village to perform for locals for 80

years. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In the village of Hongdu in a poverty-stricken county in Taihang Mountains in Shanxi province, 11 men gathered in a yard and sat on the ground. Before long a crowd had gathered around, attracted first by the men's high-pitched singing and then by the sound of the musical instruments each was playing, including the erhu, the sheng and drums.

Among those in this small, intimate audience was Ya Ni, a television producer, director and host in Zhejiang province, and one of the country's most respected television presenters.

"I'll never forget that day," she says."I didn't have a clue what they were singing about, but I was mesmerized, standing there taking in the performance until the end. Somehow I even found myself crying within."

Over the past 18 years Ya Ni's efforts to make her film have encountered countless difficulties, including her fruitless attempts to get funding for her project and her abandoning a stellar television job for what many might regard as a folly

That day in 2002 she had just finished working on a project about a local folk singer and his family, and she was about to leave the village, so at that point another project was the last thing on her mind.

ALSO READ: A notable endeavor

"I asked the locals who these men were and the answers got me really intrigued," says Ya Ni, whose family name is He, but who adopted the other name after the title of a TV program she presented.

"They were referred to as 'the men with no eyes', 'bachelors' and the 'Eighth Route Army'. That got me curious enough to decide to stay for a few more days to interview them."

That curiosity would upend her life for many years to come, and 18 years after she decided to make a film about these 11 blind musicians it is still to see the light of day.

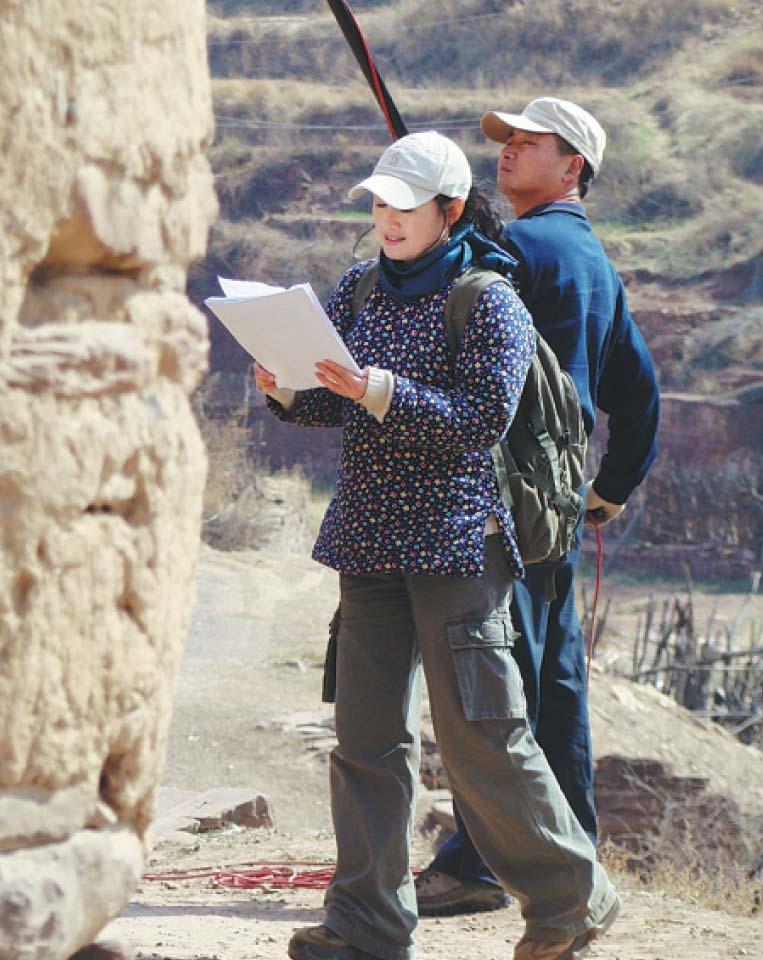

The filming site of the documentary Meiyanren. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The filming site of the documentary Meiyanren. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

However, this story goes back much further than the past two decades, to 1938, when some of these men were mere youngsters in the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team, founded that year in Zuoquan, the county in which the village of Hongdu is located. The county was one of the fields of battle in which the Eighth Route Army fought invading forces in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1939-45) from the late 1930s and where it maintained a base for about five years in the early 1940s.

Over the past 18 years Ya Ni's efforts to make her film have encountered countless difficulties-a story that itself would be worthy of a feature film-including problems in shooting on location, her fruitless attempts to get funding for her project, the close relationship she developed with the musicians, and her abandoning a stellar television job for what many might regard as a folly.

I didn't have a clue what they were singing about, but I was mesmerized, standing there taking in the performance until the end. Somehow I even found myself crying within.

Ya Ni, Chinese television producer, director and host

For all her efforts, something she did manage to produce, four years ago, was a book titled Meiyanren (Men With No Eyes), in which she told of the blind musicians' exploits in the 1930s and 40s making a living by traveling from village to village, individually, mainly in Zuoquan county, and performing for locals.

"When a blind musician reached a family's gate he would place a bench he carried with him on the ground, then sit on it and begin singing. In return the family would usually give him a meal or a little money.

"When the musicians traveled in groups, as they proceeded from place to place each would have his hand placed on the shoulder of one of the others, and a man with sight led them all. They often gave more than 200 performances a year. Given that they were blind and poor it was difficult for them to find a wife."

In addition to performing individually, the blind musicians also formed groups to perform together. A small group would consist of three or four, and a bigger one of six or seven. The percussionist usually sat in the middle, and the others playing stringed instruments such as the huqin (a two-stringed bowed instrument), the sanxian (a three-stringed plucked instrument) and bamboo flute, sat on either side.

The folk songs of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team have been included in the national intangible cultural heritage list in 2006. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The folk songs of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team have been included in the national intangible cultural heritage list in 2006. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

When the Chinese Communist Party set up the Blind Men's Publicity Team in 1938, the aim was for it not only to solidify patriotic fervor by performing local folk songs and new works the team had written about the war against the Japanese, but also to carry out various clandestine military activities. These songs vaunted the deeds of the Red Army, its heroic soldiers and the civilians who aided them in fighting their enemies.

After war was won and the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team not only remained intact but thrived with government support. Of course, all of the original members have now passed on, but the arrival of new members over the years ensured that the troupe would not simply die, and it now has seven musicians, most aged 50 or older. Some were born blind and others lost their sight as a result of accidents or illness.

Ya Ni, who was born and raised in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, graduated from the Communication University of China in Beijing in 1980 and began working with Zhejiang TV the same year. In 1989 she gained her master's degree in journalism from Zhejiang University.

Over the course of 17 years she used her own money and borrowed from others-including mortgaging her home-and used rudimentary equipment to film the blind musicians. In the beginning, she only had one colleague traveling with her to the poor county. In 2005 she gave up the television job that had given her nationwide acclaim and by then was frequently making the trek from Hangzhou to Zuoquan county, 1,200 kilometers away, spending much of her time living among the musicians, eager to get firsthand material.

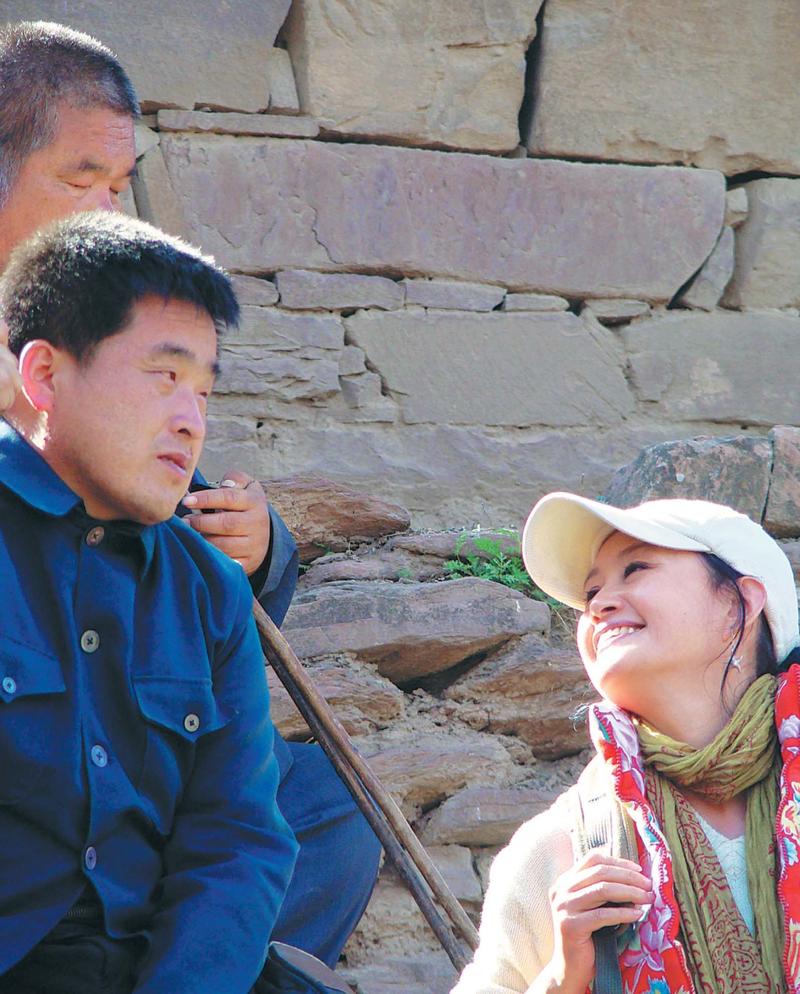

Ya Ni's interview with Liu Hongquan (left) in the village of Hongdu. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Ya Ni's interview with Liu Hongquan (left) in the village of Hongdu. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

"There's a saying in Zuoquan county's villages that when Ya Ni comes the dogs don't bark, because even they recognize me now," she says."I didn't expect making this film to become my life. I didn't just turn my camera on these blind musicians but also became friends with them, helping them solve personal problems."

Ya Ni had planned finally to release the documentary, also titled Meiyanren, this year, but had to postpone that because of the coronavirus pandemic. The documentary will be divided into four parts, she says, with the first presented in five hours split in two, and each of the remaining three parts lasting two hours. The four parts focus on different themes on three families, about their relationships, romance, friendships and the blind musicians' lives in general.

Ya Ni says that the documentary will be released when the viral outbreak ends and will provide an extraordinary and intimate portrait of life of those rarely known blind musicians.

"Many of my friends, colleagues and relatives just can't understand why I would want to devote all this time and effort to these musicians. I know full well that compared with commercial movies the appeal of documentaries is much more limited. But what makes my commitment so special is that I have recorded the story of a group of people who themselves are so special and very real. They not only embody how Chinese folk music is changing but also tell stories of humanity."

Award-winning filmmakers such as Jia Zhangke and Lu Chuan have made invaluable contributions to the documentary as consultants, she says.

This undated photo shows Liu Hongquan, leader of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

This undated photo shows Liu Hongquan, leader of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

One of Ya Ni's interviewees is Liu Hongquan, 51, who was born blind. He enjoyed listening to local folk music when he was a child and taught himself to play the erhu and the suona, a double-reeded horn.

However, Liu's father opposed his wishes to become a folk musician. After graduating from a school for the visually impaired in Taiyuan, capital of Shanxi, in 1992, Liu became a masseur, a common job for blind people. After Liu's father died in 1995 he quit that job and joined the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team, of which he is now a leader.

One of those who was with Ya Ni when she first heard the men perform in 2002 was Tian Qing, a musicologist, who has mused on what makes their performances so powerful.

"The honesty of their music has touched me so much that it has brought me to tears," he has said. "It's as if they sing to the sky not only with their voices but with their hearts as well."

... what makes my commitment so special is that I have recorded the story of a group of people who themselves are so special and very real. They not only embody how Chinese folk music is changing but also tell stories of humanity.

Ya Ni

One of the songs that has particularly impressed Tian is performed by Liu. It is titled Guang Gun Ku (A Bachelor's Bitterness) and tells 12 sad stories of a single man over 12 months. The song remains a staple of the musicians' repertoire.

Tian, who has dedicated himself to researching, collecting and recording Chinese folk songs, says Zuoquan is well-known for its rich resources of folk songs, and blind musicians are accorded a special place in Chinese music.

One of the best known blind musicians in China is Hua Yanjun (1893-1950), also known as "xia zi Abing" (blind Abing). He composed Erquan Yingyue (Moon Reflected in the Second Spring), one of the most well-known Chinese musical works, which is often performed by contemporary musicians and orchestras.

"Every blind musician has a story to tell," Tian says. "In their lives they have tasted a lot of bitterness, which is perhaps why their music is so powerful and touches listeners so deeply."

In 2003 Ya Ni and Tian took the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team to Beijing and performed at some of the capital's universities, gaining a lot of public attention. That in turn spawned more opportunities for them to perform.

"But now, by dint of urbanization, many villages have disappeared," Ya Ni says. "The blind musicians have better lives and they perform less frequently. When I look back, I still feel touched. Some of my interviewees have died but I have them alive in my documentary."

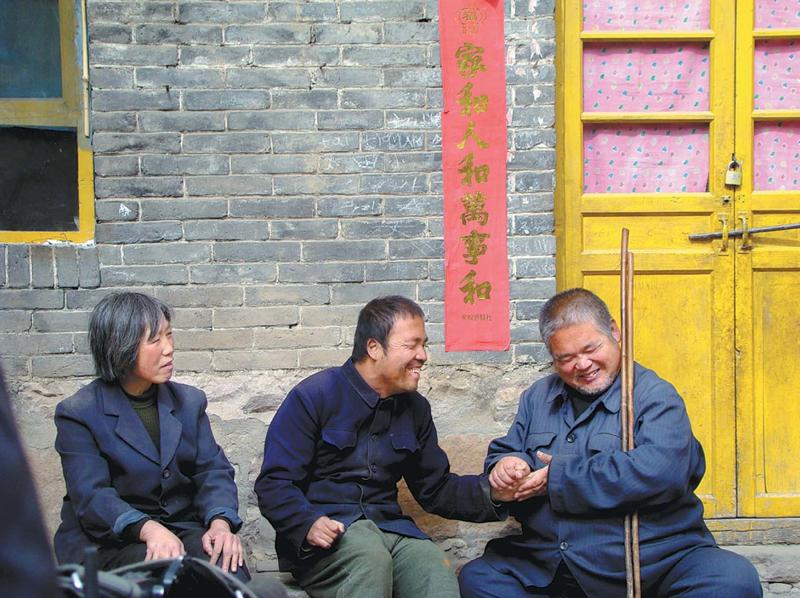

Chen Rousan (first right), the drummer of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team, passed away in 2009. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chen Rousan (first right), the drummer of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity Team, passed away in 2009. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In February one of the members of the Zuoquan Blind Men's Publicity, Wang Minghe, died, and on the day he was buried, Feb 24, Ya Ni published a tribute to him on her social media platform.

Wang, born in 1956, was the youngest child in his family and lost his sight after being ill when he was 2 years old.

He joined the troupe in 1974 and learned to sing-along piece titled Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, which takes days to perform. In 1984 he suffered a serious leg injury after falling through ice into extremely cold water, so it became difficult for him to walk through mountainous terrain, but that did not deter him from continuing to perform.

"He loved to sing and tried hard to keep up with the team," Ya Ni said."I was really sad that because of the coronavirus I couldn't attend his funeral."

After the Meiyanren documentary has had its premiere-Ya Ni hopes that will be this year-she plans to release another one, centering on a particular family in Zuoquan county. The family has six brothers, all of whom are blind, and whose sister is healthy. The sister, Chen Xizai, helped her brothers perform in the villages of Zuoquan county, and one of them, Chen Rousan, gained a reputation in the village as a fine drummer.

Chen Xizai's husband died when their son was 3 years old and all of her brothers helped her raise the boy. All brothers have since died.

They had all been musicians and made about 1 yuan for each show they performed in, saving all the proceeds for the boy, who eventually obtained a PhD degree from Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

In 2009 when Rousan died there was a big wake and funeral at which blind musicians sang almost continuously for three days. Two years later, when Chen Xizai's son returned to the village to get married and asked her to go and live with him and his wife in Shanghai, she refused.

"The men with no eyes are not 'polluted' by the outside world and they have a bright heart though they live in darkness," Ya Ni says.

"There are many true stories about them that audiences don't known. With my documentary I want to tell all of them."