On view at Tai Kwun Contemporary, a new work by Chinese video-art pioneer Zhang Peili uses the idea of sensory overload to make a compelling statement about the precarious nature of human existence. Mathew Scott reports.

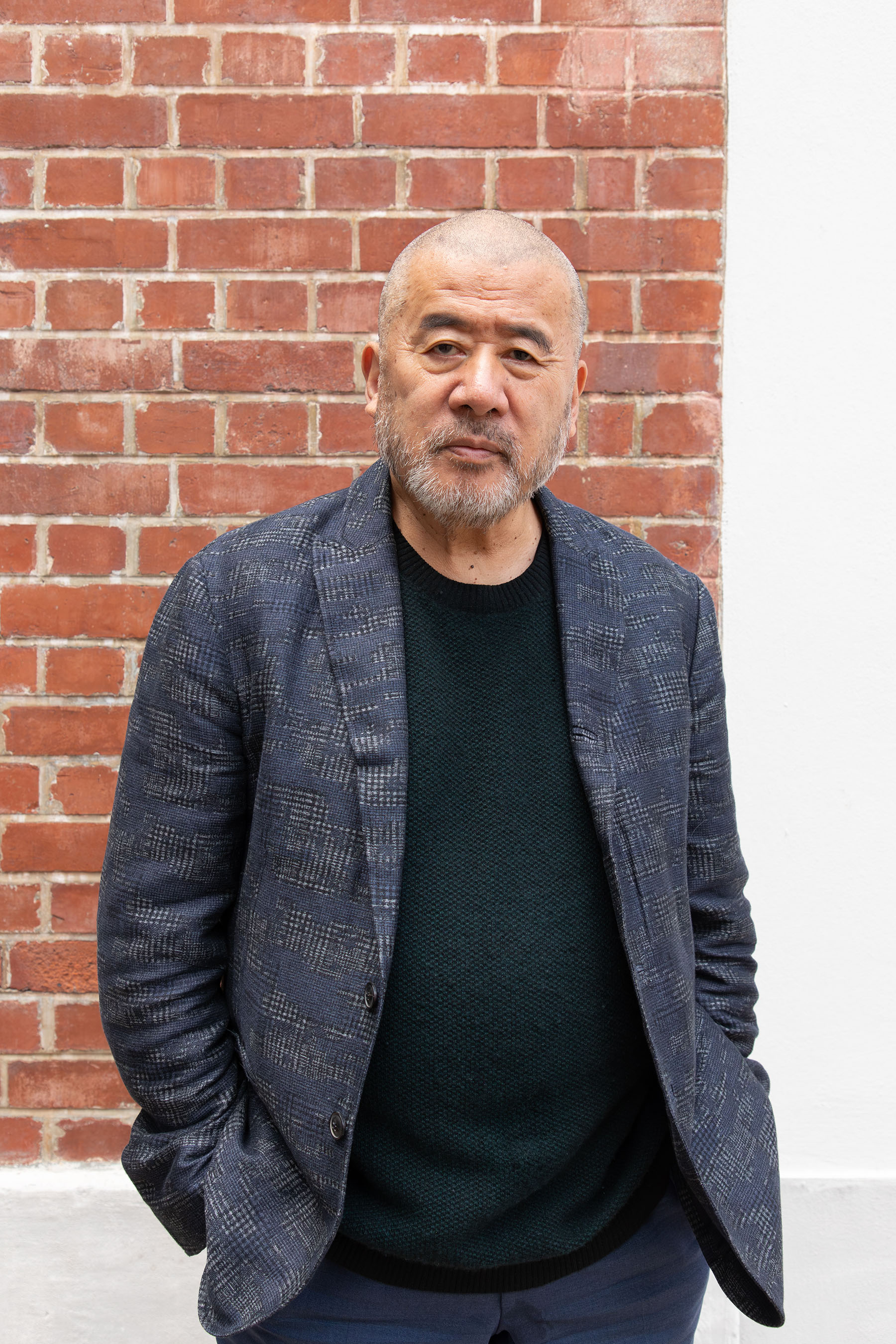

It is interesting to hear Chinese contemporary artist Zhang Peili (1958-) admit that he approached his new commission from the leading Hong Kong exhibition facility, Tai Kwun Contemporary, with some trepidation.

Often referred to as the “father of video art in China”, Zhang emerged in the late ’80s and has helped expand the art form’s scope ever since. During this time, video has moved from the fringes of the art world to almost ubiquitous use in everyday life, thanks to the proliferation of smartphones and other audiovisual recording devices.

Zhang was offered Tai Kwun’s F Hall Studio with its four vast walls to create an immersive installation. The sheer scale of the project posed “a brand-new challenge for me,” he says.

At the media preview of Zhang’s new work, A Day, it was evident that he had used the space well. Visitors stepping inside the hall are surrounded by digital screens beaming moving images from eight channels. However, soon afterward, they tend to seek out their own personal spaces within the constructed environment, and get completely immersed in the visuals playing out around them.

READ MORE: Characterful!

Commissioned as part of Tai Kwun Contemporary’s DigiRadiance series, A Day comprises montages of everyday scenes — urban landscapes, people running through a park, getting massaged, and being pushed on wheelchairs. These are alternated with news footage and surveillance camera clips.

The effect is hypnotic, even dizzying, because of the accelerated pace at which the images flicker past one’s eyes. But observe them with care, and you might just get persuaded into contemplating how everyday occurrences reflect the temporal nature of human existence. While the images used in A Day could be found randomly on anyone’s phone, Zhang has strung them together into a narrative that is compelling.

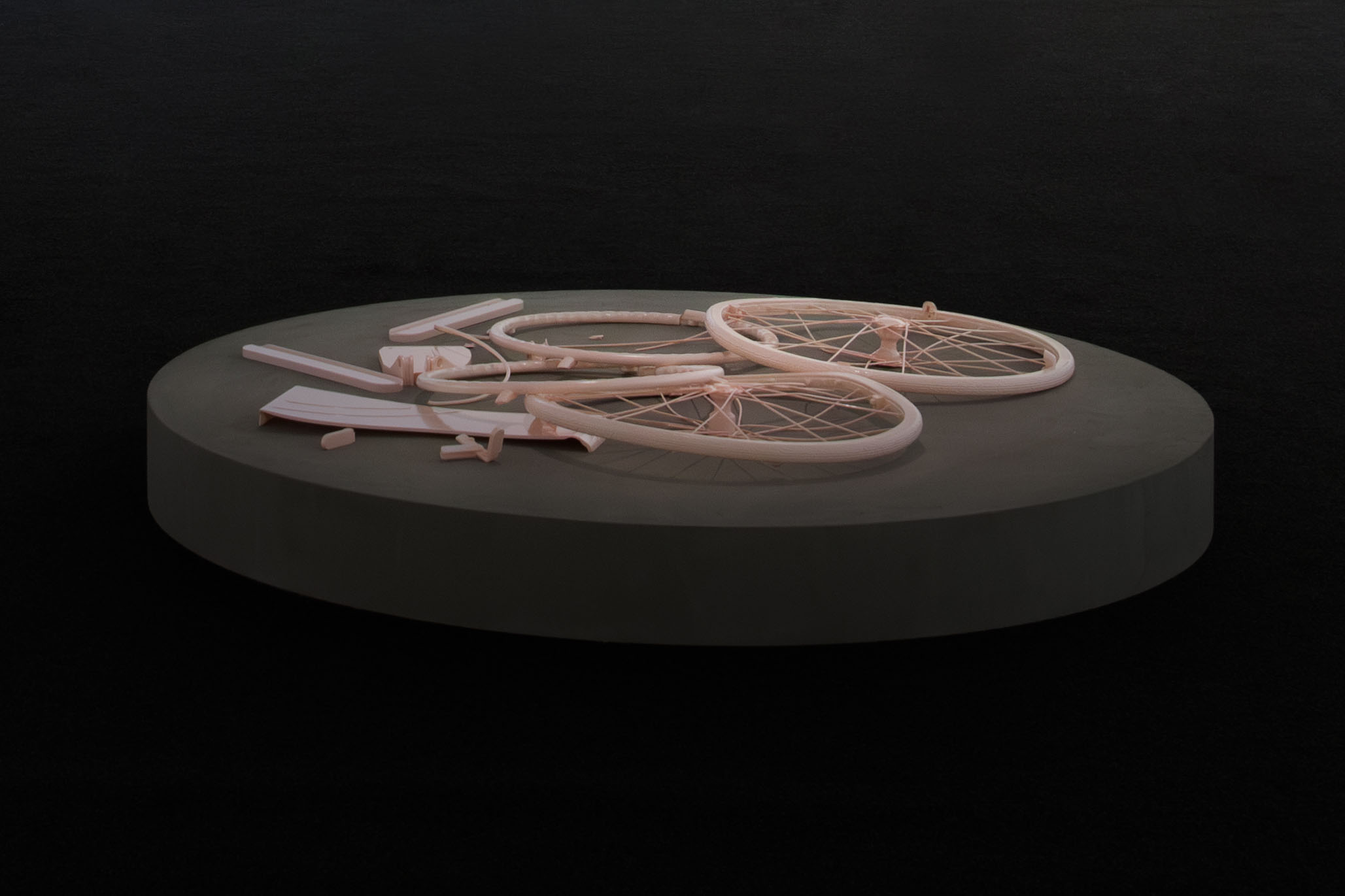

For instance, footage of wheelchairs feature prominently and might turn your mind to thoughts of decay, and even finality — a notion drummed home when in the final shot of this 12-minute experience a wheelchair falls on the ground and shatters into pieces. To underscore the point, broken remains of 3D-printed wheelchair sculptures have been placed on circular platforms on the floor. Zhang says that he wants his viewers to contemplate the transitory nature of the time and its impact on the human condition.

Pandemic traces

A Day harks back to the days of the COVID-19 pandemic, though the connection is never made obvious. The recurrence of wheelchairs and scenes shot inside an infirmary resonate with our collective memory of a debilitating crisis, experienced universally, not too long ago.

Kwok Ying, senior curator at Tai Kwun Contemporary, reveals that for the commissioned piece Zhang had wanted to explore a subject that was common and universally relatable — “life and death, limitations of our bodies” and the like.

That’s when the Tai Kwun Contemporary curatorial team came up with the theme of the pandemic and how it had demonstrated the vulnerability of the human body against the virus.

The idea resonated with Zhang. “Throughout this piece, I have emphasized a question that I have been concerned about for the past few years — the instability, uncertainty, passivity, and randomness of the human experience.”

ALSO READ: Heritage renewal

Another set of A Day images leaving a profound impression is that of people chanting a seemingly random 18-digit number, subsequently revealed to be Zhang’s national ID number. However, until the explanation, this section of the piece looked like a viral meme that I did not quite get, and that feeling of not being in on the joke reminded me that we live in age where the constant bombardment of images from “real life” has actually disconnected us from that very thing.

The rapid scrolling through news clips in A Day has a similar effect — of placing real life at a point of some remove. Zhang says that he wants his viewers to leave the room in a reflective state of mind — dragged off their own little screens, of which Zhang’s immersive digital environment is a magnified metaphor, and into reality, if you will.

Evolution of video art

Back in the ’80s, when Zhang made his first video art piece, his primary motivation was to explore the medium’s possibilities.

He emerged with a series of works focused on everyday — often mundane — activities, presented in ways that gave his audiences pause for thought. For instance, his first video piece, 30x30 (1988), lasts three hours and shows the artist in the act of shattering a mirror and then trying to put it back together.

Zhang explains that back then most people weren’t familiar with handling technology on a daily basis and hence the idea behind making videos about everyday occurrences was “to encourage the average person to use video to express themselves and to communicate with each other”.

He concedes that in the nearly four decades since 30x30, the medium has become arguably the most accessible means of artistic expression. Besides the ubiquity of mobile devices and their built-in cameras, the easy availability of cheap camera and audio equipment, as well as of apps that can handle the purely technical aspects of the art form — editing, for example — has completely democratized the art form.

READ MORE: On board with skateboards

On the flip side, easy access to technology has also lowered the barrier of entry to the field, says Zhang. “I would even say that there’s too much of it.”

Moving with the times

In her introduction to A Day, Wang Shuman, associate curator at Tai Kwun Contemporary, said, “This new work undoubtedly encompasses Zhang’s concerns across different artistic periods and allows us to better understand his artistic methods and intentions.”

Evidently, Zhang has kept up with the developments in technology, for A Day features what the piece’s promotional material lists as “data-generated images”; in other words, artificial intelligence (AI) was used in its making.

ALSO READ: A world to win

However, Zhang is cautious about the “overuse” of AI to make art, for “then it’s not about expressing your personal views on art or reality; it’s the machine speaking for you”.

He is also concerned about the way AI-assisted-or-generated art pieces can give off a “very mechanical, technical, almost cyberpunk feel”.

“I don’t want that in my work. I try to strike a balance. In terms of using AI in visual art, I’m not very opposed to the idea, and nor am I very pro-AI.”

If you go

DigiRadiance | Zhang Peili: A Day

Dates: Through Feb 20

Venue: F Hall Studio, Tai Kwun, 10 Hollywood Road, Central

www.taikwun.hk/en/programme

The writer is a freelance contributor to China Daily.