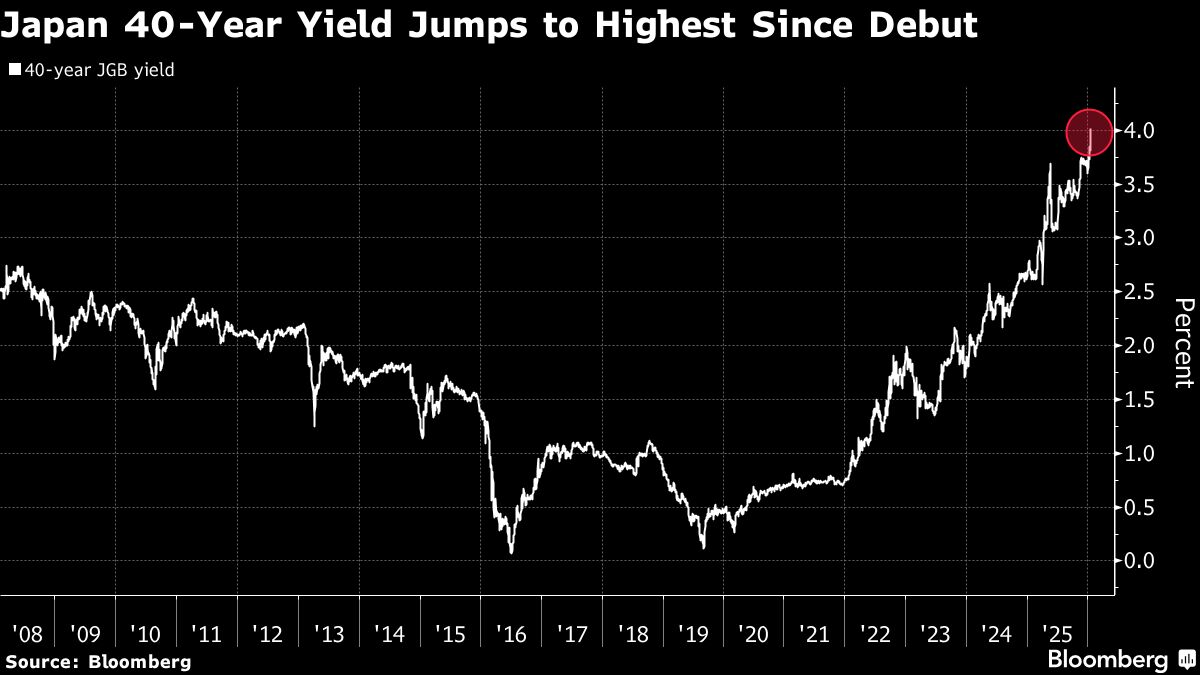

Japan’s chief government spokesperson played down the sudden meltdown in the Japanese bond market, as Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s campaign pledge helped push yields on 40-year bonds to the highest in decades.

“Long-term yields move on various factors and are determined in the market so I’ll refrain from commenting on every move, but we’re keeping a close eye on markets,” said government spokesperson Minoru Kihara on Tuesday.

“We’ll make sure to gain market trust through a sustainable fiscal policy, making our economy strong and bringing down the debt-to-GDP ratio.”

Takaichi’s proposed two-year pause of the 8 percent tax on food and non-alcoholic beverages is expected to cost roughly 5 trillion yen ($31.6 billion) per year, according to the Finance Ministry — not much less than the total amount spent on education, science and culture combined. Takaichi has sought to reassure markets that she can cover the bill without issuing additional deficit-financing bonds, but hasn’t explained what alternative revenue would fill the gap. That’s resulted in a sell off in the Japanese bond market as investors worry over the country’s already massive debt burden.

Kihara’s tone suggested the government isn’t in panic mode just yet, and will simply keep watch on market movements for now. The Bank of Japan is set to give its latest policy decision on Friday, but has clarified in the past that it could step into the markets during times of excessive volatility. Following the bank’s decision to hike last month, economists broadly expect a hold this week, with half of surveyed analysts expecting the next hike to come in July. Still, the stepping back of the central bank from its focus on bond buying as a policy tool is among the key factors feeding into nervousness and volatility.

Investors already concerned about the country’s massive debt burden have dumped government bonds this week. The rout revived concerns that Japan could see a fiscal-fears market crash similar to the one triggered by former UK leader Liz Truss, whose promise of the biggest tax cuts in half a century ultimately sank her government in a matter of weeks.

“It remains highly uncertain whether the consumption tax cut can be implemented without relying on government bond issuance,” said Ataru Okumura, a senior interest-rate strategist at SMBC Nikko Securities.

Japan’s 40-year bond yield rocketed through 4 percent Tuesday, the highest since its debut in 2007 and a first for any maturity of the nation’s sovereign debt in more than three decades. The jump in 30- and 40-year yields of more than 25 basis points was the most since the aftermath of President Donald Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs onslaught in April last year.

Takaichi seems to have bet that the tax cut will help her consolidate power in an election next month by addressing inflation, a top voter concern. But she faces a tricky balancing act of wooing voters while reassuring the market that her spending pace won’t get out of hand.

“Historically Japanese administrations have underestimated the risks of rising interest rates and yen depreciation from expansionary policy,” said Prashant Newnaha, a senior Asia-Pacific rates strategist in Singapore. “Markets are beginning to price this risk via higher neutral rates and higher term premiums and hence the absence of buyers in the JGB market.”

Takaichi announced the temporary tax cut proposal on Monday to woo voters ahead of a Feb. 8 lower-house election, but the measure could become permanent given the difficulties past governments have faced in raising the sales tax. Japan will hold an upper-house election in the summer of 2028, which is likely to increase political pressure to extend the food sales tax cut to keep voters satisfied.

“Markets are becoming more conscious of fiscal expansion,” said Takuya Hoshino, chief economist at Dai-ichi Life Research Institute. “They are finding it harder to buy when they worry about a possible acceleration of expansionary fiscal policy going forward.”

Meanwhile, even if voters were worried about Japan’s fiscal future, they don’t have many better options. Japan’s largest opposition bloc is calling for the permanent elimination of the food sales tax — arguably taking a stance that’s less fiscally cautious. The Centrist Reform Alliance aims to achieve the change by managing a sovereign wealth fund to generate financing, though details of the mechanism remain unclear.

Other parties’ suggestions cost even more. The Democratic Party for the People is arguing for a cut to the overall sales tax to 5 percent from the current 10 percent until real wages turn positive in a sustainable manner, which would cost 15 trillion yen, while right-wing newcomer Sanseito is proposing eventually cutting all sales tax to 0 percent — a move similar in scale to Truss.

Still, by one measure, Japan has more fiscal room to expand Takaichi’s pro-growth economic agenda through additional spending, as nominal growth has picked up thanks to inflation, substantially lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio. Takaichi’s tax cut plan is also worth less than 1 percent of GDP — significantly less than Truss’s proposal, which equated to the biggest tax cuts in half a century and ultimately brought down her government.

As parties in Japan jostle over tax reductions to lure voters, inflation has already been increasing Japan’s tax revenue. SMBC Nikko’s Okumura estimates the annual revenue boost would be more than 2 trillion yen, while government interest payments on the debt burden would also rise by around 2 trillion yen. That means only part of the additional tax revenue could be used for economic measures, falling far short of the 5 trillion yen needed for the food sales tax cut.

“New funding sources must be secured, or else the bulk of the funding will need to rely on new government bond issuance,” Okumura said.

Japan’s Growth Strategy Minister Minoru Kiuchi tried to reassure markets earlier Tuesday, saying that the Takaichi administration would keep fiscal discipline in mind as it considers the tax cut. Non-tax revenue and a review of excess spending are among the options to fund it, he said, adding that the government will keep bringing down the debt-to-GDP ratio.

“We’ll continue to watch market moves with a high sense of urgency,” said Kiuchi. “We’ll keep up efforts to maintain market trust.”