Youngsters from remote mountainous area overcome hurdles, soar on concert stages

Editor's note: To mark the International Day of Persons with Disabilities on Dec 3, this story highlights a journey of a choir composed of deaf children who learned how to sing through vibrations and resonance.

Li Bo, a multimedia artist and musician, said he would never forget the sound of a deaf girl's "ah "as — "a lone utterance that flooded my heart completely".

That was in 2013. The girl, Yang Weiwei, has since become a core member of Li Bo's Silence Choir — a group that would never have existed without that one sound, and one composed entirely of deaf children.

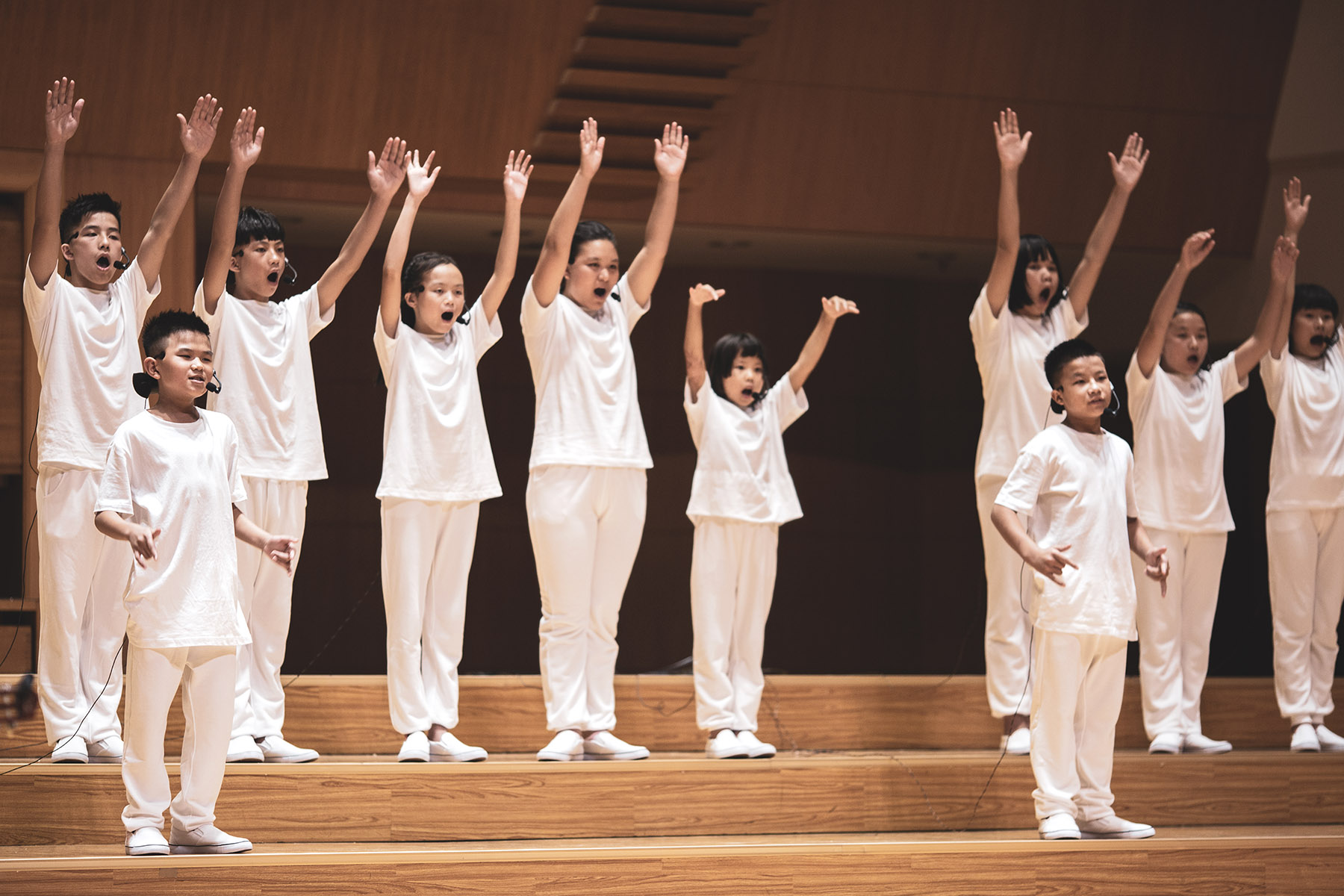

In September, the choir took the stage at Beijing's Forbidden City Concert Hall. As the performance began, the music rose — soft and ethereal — as if carried from the distant mountains where the members had once trained. Then, a single stone fell into the musical waters: the first "ah" of a lone voice. One by one, others joined — a continuous drip, a trickle, a stream, and then a gushing current.

READ MORE: Landmark gala show for impaired fans

"True equality originates from the resonance of the heart," Li said.

Yet it was a long journey — both literal and metaphorical — for Li and his fellow musician Zhang Yong, co-founders of the choir, to come to see the deaf singers as truly equal.

"We took a plane, a train, two buses, and finally a motorcycle ride to reach the school, where I first met the girl," recalled Zhang, who is based in Beijing.

Under the clouds

Nestled deep in the mountains of Lingyun county in South China's Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, the school was built specifically for local children with various disabilities.

Lingyun means "above the clouds", yet the children's hopes rarely soared that high. Behind the gates of Lingyun School the children lived in a world of their own — moving in rhythms of their own making, some of them hesitant and intimidated by the world beyond, "where people can actually hear", as Li observed.

Therefore, none of the children could understand it when Li and Zhang — "two intruders" to use their own words — told them that they were there for their voices.

"As a contemporary artist, I work with various 'materials', including sound," Li explained. "Once, while walking down the street, I heard a deaf man who had just realized he'd lost something precious. He let out a single cry — so raw and powerful that it seemed to contain every emotion he felt in that moment."

"In that moment, I knew I wanted to include the voices of the deaf in my next art and music project," said Li, whose search — aided by a volunteer organization — eventually led him and his friend to the school.

"There we were, with all our recording equipment set up, yet the children refused to cooperate. They walked past us, avoided eye contact, and when asked to make a sound, simply raised their little fingers — a gesture that meant 'no good'."

Realizing they first needed to connect with the children, Li and Zhang stayed for a week, spending entire days simply playing with them. "Somewhere along the way, we began to see how wrong we had been — forcing these deeply sensitive children to face the stark reality of their disabilities in the name of art. It was time to step back."

And then came the day when Li and Zhang decided to bid farewell to the school's headmaster. As they stood outside his office, a young girl, no more than 6 or 7, suddenly ran up to them. She took Zhang's hands in hers and let out a clear, heartfelt "ah", gazing intently into their eyes.

"She was effectively saying, 'Look, I can do it! I can do it!'" said Zhang. "We looked at each other and realized that this little girl trusted us enough to believe what we had told the children repeatedly: that their voices were truly beautiful. Trust demands commitment. Once it is built, you cannot simply walk away — you must honor it."

Tuning to vibrations

But how? The two shut themselves away in their hotel room for three days, before emerging with the idea of forming a choir.

"They still need to face their disabilities, and to redefine them on their terms, for this is the only way to shatter the cocoon of limitation our society has wrapped around them — to unfurl their own wings," said Li.

"Their music arises from their experiences and is expressed through their bodies. It answers to no aesthetics but its own, for their world does not exist on the margin — it runs in parallel to ours."

The way Zhang taught the children to sing was by tuning them to the very essence of sound — vibration.

"A child would place a hand on my throat, and I would place mine on theirs. As we both made the 'ah' sound, the air between us trembled. They could feel the pulse of my voice beneath their palms, and I could feel theirs searching for it. That's when they understood: to reach the same pitch, they had to let their own vocal cords hum the way mine did. They learned to listen not with their ears, but with their bodies — to feel the resonance rising through the chest, echoing in the head, and merging into a sound that was wholly their own."

When practicing alone, the children used a tuning meter — the kind musicians use to fine-tune their instruments. As the needle steadied at the desired pitch, the child would memorize the vibration running through their body at that moment. They would repeat this process thousands of times, until the feeling itself became memory — until their body muscles remembered how to produce a sound that corresponded to a musical note.

"In the professional world of music, this is called absolute pitch, or perfect pitch — the ability to hit a note without any reference tone. Even trained musicians usually require years of practice to develop it," Zhang said.

"The idea is simple: if each child can sing a single note, together they can produce a full range of notes that form a piece of music. And we welcomed all who were willing to try and who stayed with us."

Yet in practice, several children had chosen the same note. "That's perfectly fine," Zhang said. "I want them to find their own comfort zone, the note that feels most natural to them. The fact that their comfort zones overlapped didn't bother me at all. Once they open that door, they will slowly stretch beyond it, discovering new notes and expanding their range."

These days, some veteran members of the group, including Yang, can sing three notes.

New horizons

In May 2017, just over three years after the choir was formed, its 14 members made their debut in the assembly hall of Lingyun county, performing a one-minute etude specially composed by Zhang for the occasion.

"The performance was far from perfect. But as the 'ah' sounds of varying pitches rose and fell like waves breaking on the shore, I realized that these children — there were 15 of them — had started to ride the tides of their lives — hesitantly, yet with joy," said Zhang, accompanying them on his self-invented instrument — a fusion of a bass guitar and a seven-stringed traditional Chinese instrument known as the guqin.

Two months later, the children arrived in Xiamen, Fujian province, to take part in its annual music festival. Their performance, extended from one minute to three, seemed almost secondary — everything else was so astonishingly new for them. It was the children's first time on a plane, their first visit to an amusement park, and their first glimpse of the sea.

"They didn't just glance at the water — they plunged straight in, despite never having learned to swim. One by one, we had to drag them back — it was chaotic, exhausting yet utterly exhilarating," Li recalled.

Among the audience at the choir's performance in Xiamen was a director from Beijing's Forbidden City Concert Hall. An invitation was soon extended, and on Aug 4, 2018, the children — some entering adolescence — found themselves standing on the stage of one of China's most venerated venues.

"The audience sat close to the stage — so close that by the end, nearly half were wiping away tears," Zhang recalled. This time, the piece was extended to 12 minutes.

The Beijing concert brought a wave of public attention.

"People spoke of it as a worthy act of charity," said Li. "But I keep asking myself — who were the givers, and who were the receivers? It's true that we helped the children step beyond their enclosed world. Yet through their voices — and their disabilities — they compelled us to confront the boundaries of our perception, as well as our own quiet inability to face our limitations, which can be debilitating in itself."

One thing Li has consistently refused is to enter the choir in competitions, because "our performers should not be judged by anyone — no matter how celebrated they may be as singers and musicians — who inhabit a hearing-centric world".

Back in their home county, people's attitudes toward the children changed dramatically.

"By going to Beijing, they've done something most of their fellow townspeople never have," Li said.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit, bringing everything to a standstill. Some members left the choir; others, growing older, transferred from Lingyun School to a special-education high school in Guilin, a city in Guangxi, to continue their studies and learn vocational skills. Li and Zhang followed them there, settling into the new school and recruiting fresh members once the pandemic was over.

Emotional comeback

The choir's performance at Beijing's Forbidden City Concert Hall in September was an emotional comeback. Out of its 15 members, three, including Yang Weiwei, have been with the choir since 2013. The oldest member is 21, and the youngest is 12.

Before the performance began, each audience member received a printed copy of a handwritten letter from a choir member. Most described themselves as quiet, and almost all expressed a simple wish: to find a well-paying job so their parents would no longer have to work so hard.

"Gratitude — that's the feeling I've received most often from these children," Zhang said. "Even though they were so often overlooked, or even ridiculed — sometimes within their own homes — they remain astonishingly tender, able to sense the heaviness in your heart the moment it arises."

In fact, some choir members might have learned to speak if not for the poverty they were born into. "They couldn't afford a cochlear implant — and even if they could, the cost of speech training and ongoing maintenance would still be far beyond their families' means," Zhang said.

The performance lasted an hour and included pieces performed in sign language, though the singing — accompanied by Zhang's specially composed music titled the Trilogy of Silence — remained its emotional core. As the concert unfolded, the music gradually brightened; its tempo quickened, and the singing began to bubble and skip like sunlight dancing over a river. "It's directly inspired by the children frolicking and playing with us," Zhang said.

At last, the music surged toward its crescendo. Each "ah" soared and stretched, striking against the very walls of the singers' vocal cords. The river became a roaring torrent — overflowing, resonating, and carrying everything, every strand of emotion, in its unstoppable wake.

"For generations, deaf individuals were simply labeled 'deaf and mute'. No one paused to consider whether they could make a sound — because sound without words was deemed meaningless. The Silence Choir tears through that assumption, revealing the truth and beauty of voices long dismissed," said Li.

"Our performers cannot hear what they sing — or, to put it more precisely, they can only hear it within themselves. Yet it is their voice — once lost, but ultimately reclaimed — that led us to search for our own voices."

ALSO READ: German couple devote lives to deaf kids in Changsha

For Zhang, the very name of the choir, contradictory as it appears, contains a deeply spiritual side. Laozi, philosopher and founder of Daoism who lived in the 6th century BC, once said, "True accomplishment wears the guise of incompleteness; true abundance carries the hush of emptiness …Great eloquence hesitates; and the deepest music whispers in silence."

"All we've ever wanted," Zhang said, "is for these kids to recognize themselves as creative individuals, entitled to live their lives to the fullest."

Li recalled a moment of profound silence at the end of the choir's performance in Xiamen.

"I was conducting on stage, my back to the audience. Normally, when the final note fades, you'd expect applause. But that time — nothing. Absolute stillness," he said.

"I waited, and the silence continued — so complete it almost rang in my ears. Then I turned around — and there they were, every single person, holding up their thumbs."

Contact the writers at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn