Major advances made, with neural technology aiding movement in clinical phase

In a nursing home in Langfang, Hebei province, Wang Ming stares at the phone near his pillow.

The screen lights up — a message from a patient-support WeChat group pops up, discussing the latest treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.But he cannot reach out to tap it. His arms hang "like limp noodles", with only slight movement remaining in his right fingers.

"If brain-computer interface (technology) could allow me to pick up the phone myself," he said, "even if it's just to open WeChat, I would be content."

READ MORE: China moves ahead with research into brain-computer interfaces

Wang is an ALS patient. Six years into the disease, he has only weak muscle control throughout his body. He is one of more than 500 patients who have signed up for clinical trials of BCI — and is among the majority still on the waiting list.

BCI technology functions as a digital bridge for the nervous system. When diseases like ALS or spinal cord injuries damage the neural pathways between the brain and muscles, BCI systems can bypass the blockage.

"BCI is not science fiction — it is a bridge," said Professor Qu Yan, director of neurosurgery at the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Air Force Medical University of the People's Liberation Army, also known as the Tangdu Hospital, in Xi'an, Shaanxi province.

"When spinal cord injury or motor neuron disease severs the neural pathway between the brain and limbs, BCI can bypass the damaged area, capture brain signals directly, decode them, and use them to control external devices or stimulate muscles," he said, explaining how BCI works.

"For example, if a patient sees a flame and wants to move away, that 'wanting' signal is captured by the chip and converted into a command to move the hand," he added.

While the foundational BCI research began decades ago in the West, Chinese teams are now rapidly advancing the technology.

In July 2025, Nature reported that "China is rising swiftly in the field of brain-computer interfaces", with devices that even outperform Elon Musk's Neuralink project in certain aspects.

"Although China does not have as long a research history in the field as the United States, development is extremely fast," Qu said, noting China's advantages in medical infrastructure and its population scale for testing.

Patients' hopes lifted

The BCI device developed by Shanghai StairMed is particularly remarkable. With 64 electrodes — each only 1 percent of the width of a human hair — it is one of the smallest and least invasive implantable BCIs in the world. The first male recipient has already used it to play chess and video racing games.

Meanwhile, other devices have taken a different technical approach. One involves placing eight probes on the dura mater, the protective outer layer of the brain, to help paralyzed individuals restore hand movement through pneumatic gloves. The first patient to receive this device, implanted in October 2023, can now eat and drink independently.

"We already lead in algorithm, implant device miniaturization and minimally invasive techniques," said a doctor involved in the clinical research. "China excels in the speed and accuracy of algorithmic decoding."

However, for patients and their families, BCI is not about technological competition — it is about hope for survival and a better life.

"Our greatest wish is for him to drink water and use the bathroom on his own," said a Tibetan daughter who signed up her ALS-afflicted father for the trial.

"Even just a little movement would make an enormous difference in our quality of life."

Lu Sheng, who has cared for his wife for four years, puts it more bluntly: "If she could use the toilet by herself, I would be content."

"Over the years, we've tried many treatments and been cheated many times. We've spent almost all our savings — over 400,000 yuan ($56,185) — on treating this illness, yet we still see no hope for a cure, or even for slowing its progress," Lu said.

"I can no longer carry her. I hope BCI technology can bring us a final glimmer of light," he said.

Many patients learn about BCI through patient groups or television news. One patient once saw a case on CCTV about another patient at Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University who could hold a cup after surgery. Two years have passed, and he has seen no follow-up report.

"I don't know if the technology succeeded or stalled," he said, "but I am willing to try."

A common refrain among patients and families is their refusal to give up on the technology. Despite high hopes, the clinical application of BCI still faces many obstacles.

Stringent screening is the first hurdle for candidates for the procedure. Patients should be in the proper age range, must not have other serious illnesses, and have a long enough life expectancy and strong family support.

"We screened 500 people and not one was a perfect fit," said the doctor who had been involved in clinical research. "Some hospitals screen 800 patients before finding one suitable candidate."

Surgical risk is another major concern for families. "After all, it's craniotomy — could there be infection? How long will the chip last? These are our worries," said the Tibetan daughter.

The ongoing financial burden is also a reality. Although the BCI surgery and device are free during clinical trials, the cost of treating and caring for the disease itself remains high. One patient's family said that medication alone costs nearly 80,000 yuan per year.

Family decision-making is a particularly Chinese dilemma.

"If the patient wants it but the family does not, it cannot happen," said Qu.

"Families worry that care is already exhausting — surgery would only add to the burden."

Clinical realities

At present, BCI can only achieve basic movement control, such as gripping a cup or playing simple games. The next focus is on language decoding and more complex motor control.

"Right now, we are just going slowly from 0 to 1, and in the future, we will go faster from 1 to 100," said Qu, the professor.

In July 2024, Shanghai surgeons implanted a device with 256 probes into the superior parietal cortex of a female epilepsy patient. After two weeks of practice, she could use social media apps and control a wheelchair with the device.

In December, the same team also implanted probes into a female epilepsy patient with a tumor in her brain's language processing area. The user could communicate in Mandarin at 50 words per minute with a delay of only 100 milliseconds — the first time BCI technology has been used for real-time decoding of Mandarin.

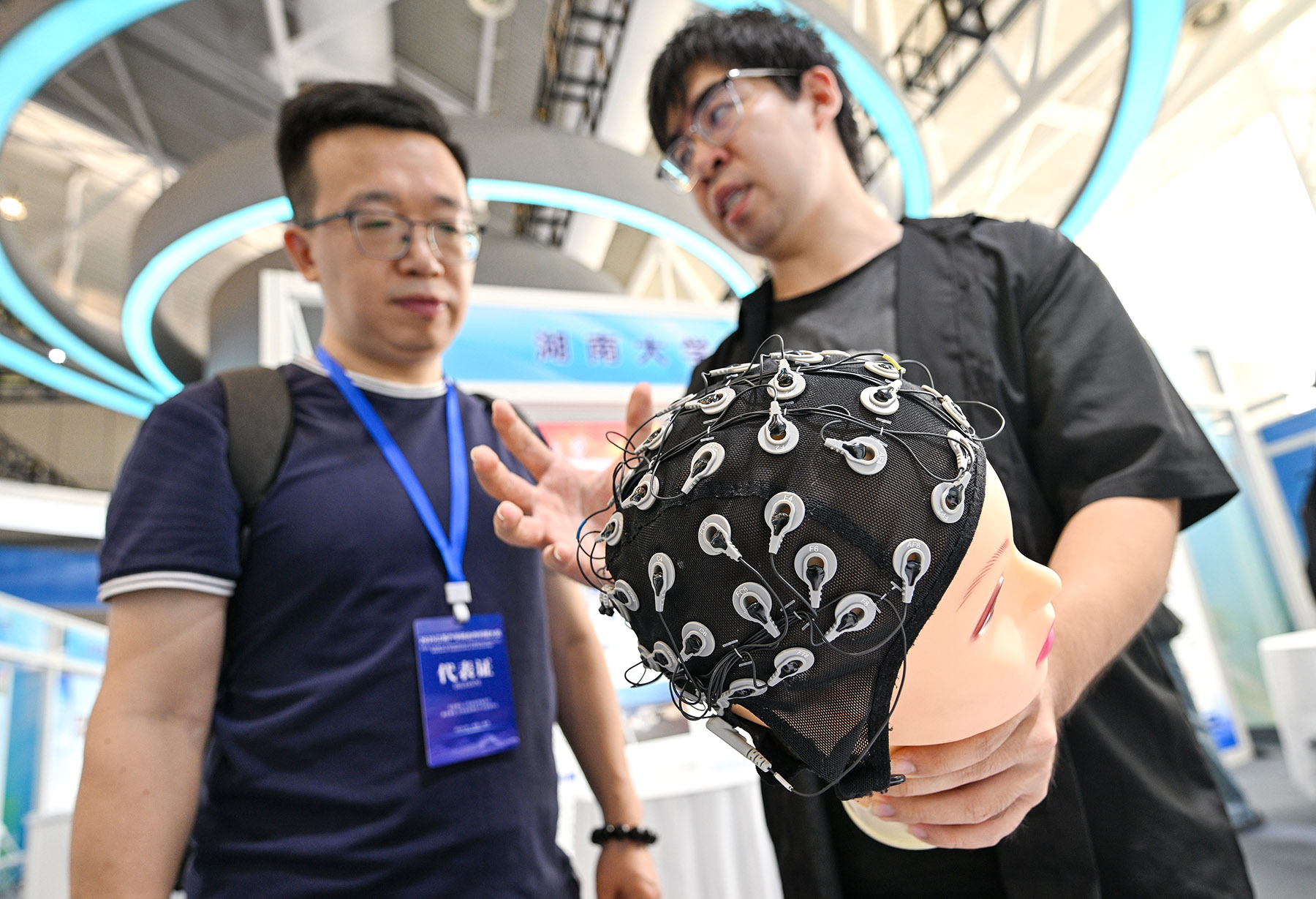

Non-invasive BCI is also another key area of development. Chinese teams are developing head-mounted devices to avoid craniotomy. However, at present the signals weaken significantly after passing through the skull, making the technology more challenging.

Wang in the Langfang nursing home said he is willing to take the risk. "If the effect is immediate, I am willing to try. I cannot wait much longer," he said.

As of now, no BCI device has been officially approved for the commercial medical market in China. All reported "success cases" remain in the clinical trial stage.

ALSO READ: Girl with epilepsy gets novel implant in Guangzhou

Wang is still waiting in the nursing home for an evaluation notice. In summer, he heard that recent hot weather had delayed hospital evaluations, and remote evaluations will have to wait until later.

He still stares at his phone every day, reading messages in the patient group. Some share news of new drug trials, some discuss care experiences, and occasionally someone forwards news about BCI.

"I know it may not be my turn," he said, "but as long as there is hope, I am willing to wait."

Contact the writers at weiwangyu@chinadaily.com.cn