Tantalizing clues point to a network of Yuan structures in the Forbidden City, as experts search for more proof, Wang Kaihao reports.

As the royal palace of China from 1420 to 1911 and where 24 emperors of Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties lived, the Forbidden City in Beijing, officially known as the Palace Museum today, showcases the charm of architectural splendor in the heart of the capital.

But it still harbors intrigue. Beneath its floors, there probably lies an even older imperial city whose legend still resonates both at home and abroad.

Thanks to a decade's archaeological research, puzzling discoveries indicating Kublai Khan's palaces have emerged, ushering people to imagine a bigger picture of a mighty metropolis of Dadu ("the grand capital") on the node of cultural exchange.

Xu Haifeng, director of the archaeology department of the Palace Museum, leads his team to conduct excavations amid the standing palaces to sift for clues surrounding the beginning of the Forbidden City in the early 15th century.

It is not easy to conduct archaeological excavations in the Palace Museum.

"Layers of relics from different periods are compressed vertically below the well-preserved palaces," Xu says. "We can clean the ground surface elsewhere to conduct excavations. However, you know, we cannot do this in the Forbidden City. Maintaining an intact landscape is the prerequisite to do any work here."

The aged grounds and ditches that have naturally cracked and eroded in the open air, for example, offer a rare opportunity to dig, which Xu dubs as "minimally invasive surgery".

Palaces of the Mongols-ruled Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) have thus yielded scattered though tantalizing clues.

In 2015, Yuan Dynasty constructional foundations were found near the Longzong Gate ("gate of thriving imperial clan") in the west of the Forbidden City. It was the first time Yuan stratum was archaeologically excavated within the red walls of the former imperial palace, according to Xu.

A new round of excavations began in 2020, also in the west part of the museum, and focused on the ruins of the former Qing Dynasty royal workshop, known as Zaobanchu. Once again, Yuan imperial architectural foundations and constructional components were unearthed.

When China Daily reporters visited the site last week, Xu and his colleagues were still cleaning the architectural bases in a newly excavated pit. These rammed earth bases with layered crushed bricks and compacted clay were buried about 2 meters under the current ground surface.

As an experienced archaeologist, Xu could immediately tell its typical Yuan elements from the stone patterns and the constructional method.

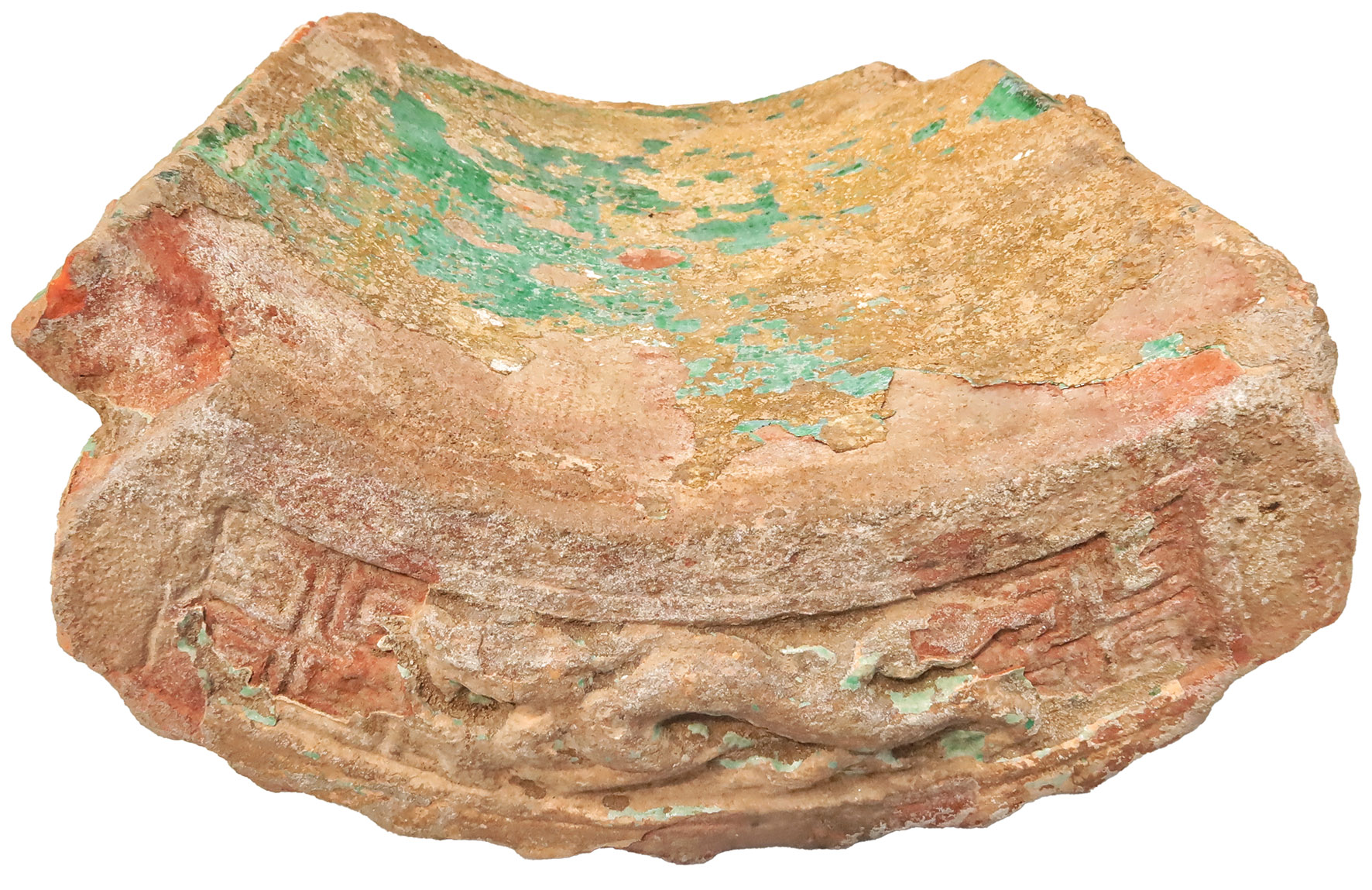

Tiles, roof decorations and bricks with dragon-shape reliefs seem to transfer viewers to an era of prosperity.

"Dragons reveal the imperial identity of our findings," Xu explains. "Compared with dragons from later Ming and Qing dynasties, whose formats became relatively fixed, Yuan dragons were more abundant in colors and shapes. They were more vivid looking."

Footprints of exchange

It is said that the iconic Venetian traveler Marco Polo was commissioned by Kublai Khan, the Yuan founding ruler, as an official to serve the dynasty.

As Yuan-era canals and ruins of earthen city walls give modern Beijing a unique identity, the whereabouts of the Khan's imperial palaces, mentioned in Marco Polo's poetic descriptions, remain shrouded in myth.

"The roof is very high. The walls of the halls and chambers are all covered with gold and silver, and decorated with pictures of dragons, beasts, birds, knights and idols, and other things," according to a quote from The Travels of Marco Polo. The traveler hailed Beijing as Khanbaliq, or Khan's city.

"The exterior of the roof is colored with vermilion, yellow, green, blue and other hues, which are covered with a varnish so fine and exquisite that they shine like crystal, and lend a resplendent luster to the palace as seen for a great way round..."

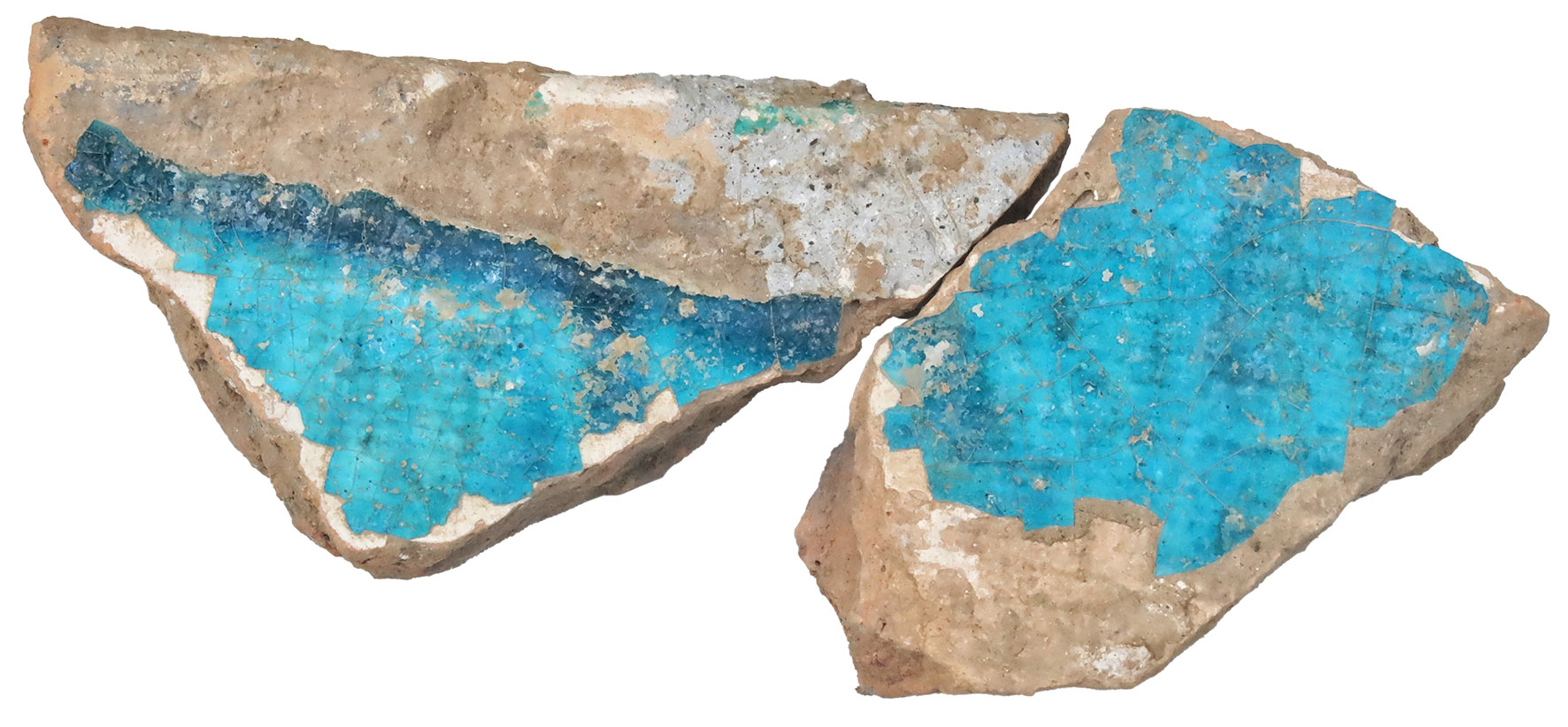

For Xu's team, discoveries of broken "peacock blue" glazed pieces from the excavation pits, in spite of their imperfect condition, seem to crystallize the ostentatious lines.

This ceramic variety originating from West Asia was primarily used as vessel decoration, Xu explains. Archaeological evidence indicates that these wares were imported to China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and the following Five Dynasties (907-960). But their influence on domestic porcelain manufacturing only became crucial centuries later, after their localized production emerged under Mongol rule.

"This shift was fundamentally enabled by its vast Eurasian territory," Xu says. "It facilitated trade exchanges and cultural communications."

Yuan-era Mongol elites thus favored the vibrant azure hue reminiscent of celestial depths. That not only saw surging popularity for the signature blue-and-white ceramic vessels, but also led to extensive application of the peacock blue glaze in palace complexes and ceremonial architecture.

"Our scientific analyses of unearthed artifacts from the Forbidden City revealed that material of their bodies matches loess that is widely distributed in northern China," Xu says. "And the glaze formula is identical to architectural elements excavated from local glazes in Beijing."

That echoes a description in the 14th-century documentation History of Yuan: "Four glazed ceramic kilns existed in the city of Dadu."

As Yuan palaces absorbed elements from afar, its features also appeared elsewhere.

From 2023 to 2024, Wu Wei, an archaeologist with Xu's team, undertook comparative studies in the Thang Long Imperial Citadel in Hanoi, Vietnam. The citadel was the center of the Vietnamese monarchy from the 11th to the 18th century. In Vietnam, the era corresponding to Yuan was the Tran Dynasty (1225-1400).

"Palace architecture from this period closely resembles contemporary Yuan construction practices," he says. "Both employed similar techniques for foundation groundwork for buildings. In Thang Long, molded-pattern square tiles used in flooring around structures featured geometric motifs identical to those prevalent on decorative paving blocks of Yuan.

"These parallels in imperial architecture highlight sustained cultural exchange," Wu adds.

When researchers see the Forbidden City from a wider horizon, they may gain some new understandings on Yuan's influence on this place.

Yudetang ("the hall of bathed virtue") is an exceptional place amid the traditional Chinese construction of the Palace Museum. This Islamic-style building with a dome in the southwest of the compound, was generally considered to be a bath, but its origins remain vague.

Wang Guangyao, a researcher with the Palace Museum, supports the theory that it is a rare intact bath left from the Yuan Dynasty based on rigid analyses of white porcelain on the inner walls of the building.

"It also matches historical documentation claiming white porcelain was used on Yuan palaces," he says.

READ MORE: A real gem of a story

Wang also found its oven even resembles Roman-style counterparts across Europe and West Asia.

How could the technology come here from such a distant place?

In 2020, the discovery of a Roman-style bath in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, dating back to the 10th to 13th century, offers a key link.

"Huihu people from that region then yielded to Mongols' westwards expedition and enjoyed high social status during the Yuan Dynasty," Wang says. "They may have naturally introduced their fashion of bath into Beijing then."

"From small details, we can see a big picture of how different civilizations exchanged and bred creativity," Xu says.

Decoding hidden history

In 2024, the Beijing Central Axis: A Building Ensemble Exhibiting the Ideal Order of the Chinese Capital was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. A series of national ceremonial and former imperial buildings since the Ming Dynasty, including the Forbidden City, now line the 7.8-kilometer-long axis and thus consolidate its role as "the backbone of Beijing".

However, questions surrounding its origins in the 13th century still await to be answered.

In the early 1970s, archaeologists unearthed a section of Yuan Dynasty central axis road in Jingshan Park to the north of the Forbidden City, creating a theory that the location of the central axis has never changed.

Decades later, Xu's findings may actually prove it.

"We haven't excavated an entire Yuan palace, due to the fact the core area of Beijing was a group of overlapped layers," Xu says.

"But the constructional foundations have already left us many crucial references.

"The Central Axis lasted from Yuan through Ming to Qing dynasties and the city layout continues to reflect ancient Chinese ideals of national governance," he explains.

"It's like a continuous lineage of Chinese civilization."

He adds: "The city of Dadu thus remains a milestone in the history of ancient Chinese capital cities and is the foundation of Ming-Qing Beijing centering the Forbidden City, which finally reaches the peak of the evolution."

However mighty Dadu might be, when Ming Dynasty rose to drive Mongol rulers northwards, its heyday came to an end. Nanjing in present-day Jiangsu province became the national capital.

"Historical recordings on the destiny of Dadu after the fall of the Yuan Dynasty are severely lacking," Li Xieping, a researcher with the Palace Museum, says.

"Zhu Di, a Ming prince, constructed his mansion in Beijing. Military fortifications were built. But these don't necessarily mean the Yuan imperial palaces were brought down."

After winning a fierce civil war for the throne, Zhu Di became the emperor, and chose to come back to where he resided. In 1420, he moved the capital back to Beijing from Nanjing when construction of the Forbidden City was completed.

Some parts of the Yuan imperial palaces may have survived.

Duanhong Bridge ("bridge of broken rainbows") in the Forbidden City is probably such an example.

Visitors thronging the bridge often pause to take photos of the lion statues, which have become popular on social media. Yet, they frequently overlook the dragon carvings on the railings. These dragons, more refined than their counterparts on other bridges in the palace, stand out as exemplary Yuan-era motifs.

Xu says, "They're typical Yuan-era dragons. The decorations surpass those of any other bridge in the Forbidden City."

ALSO READ: Palace's hidden glories unearthed

Many people believe this is what Dadu left for the Forbidden City. However, after digging below the bridge, Xu has not found Yuan Dynasty stratum.

"You cannot rule out the possibility that artisans moved the bridge components from somewhere else," he remains cautious.

He once found another case in the Forbidden City that Ming artisans use Yuan flooring bricks to build a pool.

"Yuan palaces were not entirely demolished," he says. "It's a kind of inheritance to make full use of old materials."

Xu understands it is always a tough mission to trace Yuan clues in the Forbidden City.

"Generations of archaeologists will strive for that goal," he says. "Hopefully, veils of the Khan's city will be lifted step by step."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn