Dunhuang Museum is a wellspring of history and culture on the edge of one of our planet's most foreboding deserts, Erik Nilsson and Hu Yumeng report.

The Dunhuang Museum is a newfound fount of history in Gansu province's desert — an oasis from which the past wells up into the present.

It's a grand theater that pulls back the curtain to reveal the full ensemble of roles people played here. It gives voice to deities and ordinary people alike — from the holy immortals of the Mogao Grottoes' artworks to the flesh-and-blood merchants, pilgrims and soldiers who brought this ancient crossroads to life. Their dialogue echoes over millennia to speak to us today.

To understand the stage upon which Dunhuang's drama would unfold, we must gaze beyond the fanfare of the Han (206 BC-AD 220) sentries and Tang (618-907) merchants who star in its most iconic scenes of militarization and commercialization.

READ MORE: Journey through time, stars and flavors

Peering below the surface, we discover the deeper currents of history that made their performances possible where water permeated parched wilderness.

The main ingredients of Dunhuang's initial alchemy were water and bronze, before the silk that wove its golden age.

Shining beyond bronze

The museum's oldest artifacts — simple stone tools and pottery — reveal lives scratched out of this scorched wilderness by the Qiang and Rong tribes of the Bronze Age Huoshaogou civilization around 3,500 years ago. They thrived parallel to the protohistoric Xia Dynasty (c. 21st century-16th century BC) in China's distant heartland.

Following this opening act, turmoil erupted during the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) until the fleeting Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) briefly unified the domain. This ushered in a new cast of characters who took center stage on this outlying wing of the Central Plains' empire. The Wusun, Rouzhi and Saka peoples — fearsome equestrian nomads native to the Central Asian steppe — galloped in to dominate this arid expanse.

A plot twist came with the arrival of a new force from the north in the second century BC, when the audacious Xiongnu (Huns) stormed into the Hexi Corridor. They crushed the Rouzhi and allied with the Qiang, coalescing like a cloud threatening to thunder over the fledgling Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24).

Yet, while these foreign armies marched east, second-century explorer and diplomat Zhang Qian ventured west to seek peace and prosperity beyond the empire's borders. The Xiongnu captured and imprisoned him for a decade. Yet, he returned to the emperor with a counterintuitive proposition — to envision the frontier as a gateway for the flow of goods, rather than just a military breach to seal shut.

Command and control

This inspired Han Emperor Wu to dispatch general Huo Qubing to reclaim this vital choke point between the Qilian Mountains to the south and the Mazong and Heli ranges to the north. Consequently, Dunhuang prefecture was officially established in 111 BC as a sanctuary from the brutalities of nature and humankind.

Emperor Wu commanded the construction of an immense defensive and administrative network — stretching over 2,000 kilometers, from the Yellow River's silty banks to Dunhuang's dusty periphery. Builders erected a stretch of the Great Wall that threaded together a patchwork of forts, beacon towers and ramparts to defend the prefecture and secure Hexi, fending off invaders while beckoning traders.

Models at the museum show how these structures were assembled using local materials. Laborers stacked poplar logs and slathered yellow clay churned with sand onto bundles of tamarisk and reeds, reshaping the earth under their feet to redefine the empire's horizon as far as the eye could see.

These soldiers' footprints have long since blown away in the sands of time, but their footwear — cotton, hemp and fur socks — has marched across centuries and stands still in the museum today.

They're crude fabrics compared with the exhibits of Han silk and brocades that these border guards protected with their very lives.

The sweat spent to feed Hexi's garrisons can still be imagined dripping from the displays of a Han-era millstone, bronze plow and other hand tools wielded by the soldiers-cum-farmers who cultivated the state-owned croplands that sustained the troops.

Likewise, the bloodshed that fertilized the empire's dominion feels visceral in the exhibits of iron swords, crossbow triggers and bronze arrowheads once wielded by Han watchmen.

Dunhuang served as a threshold of multiple dualities. It was the last outpost for those departing westward and the first intake for those trekking east from the Taklimakan Desert — whose name translates as "Place of Abandonment". It was here that caravans, having endured the barren wilderness, would sip from the fountainhead of civilization before stepping into the empire.

Heritage as cargo

Their most precious cargo was invisible, even unintentional — but world-changing.

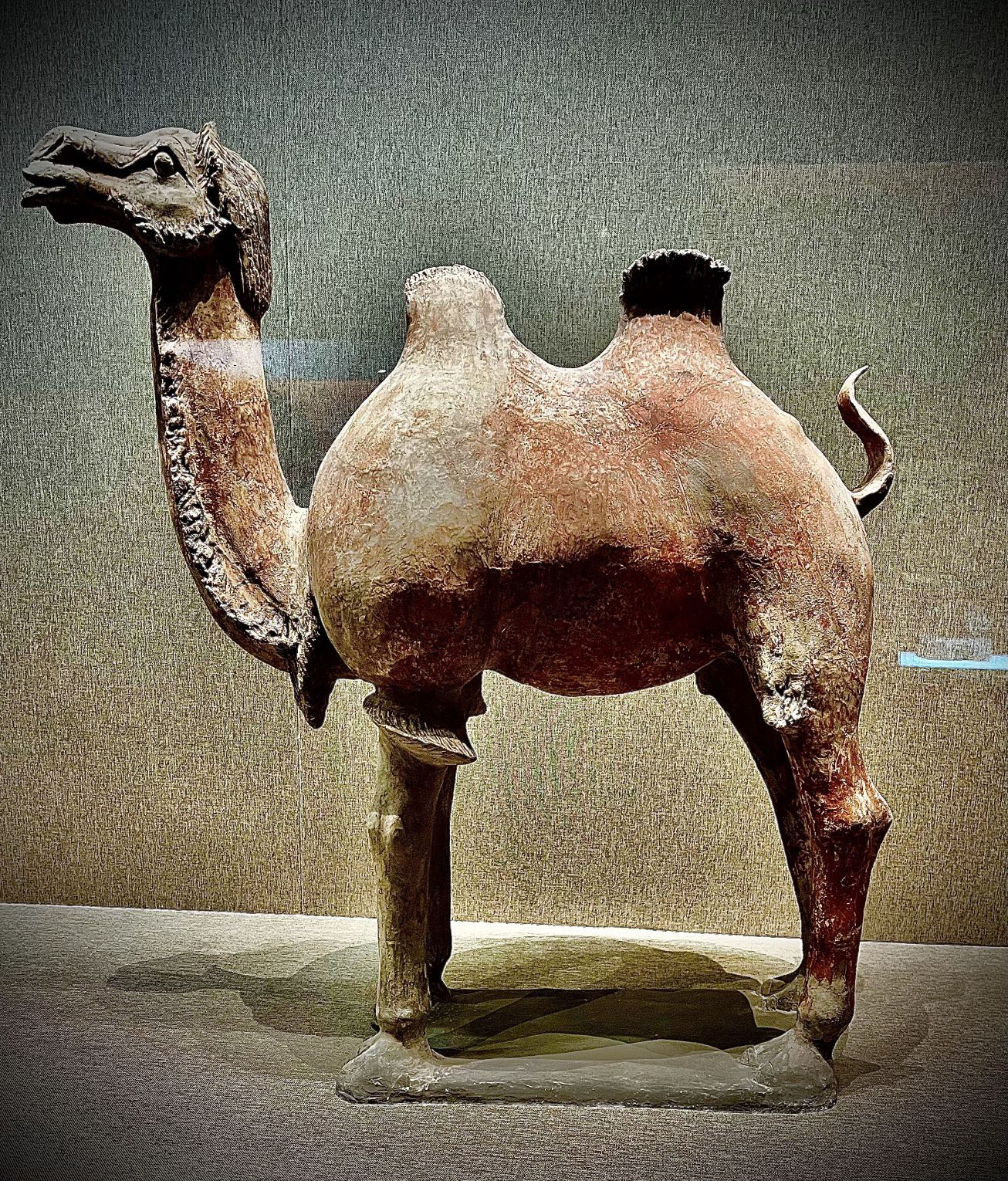

The camels that plodded along the Silk Road carried not only goods and people but also ideas and beliefs, positioning Dunhuang as an intersection of commercial and cultural crossroads.

These civilizational exchanges wrought intangible treasures that outlasted most physical commodities, whose surviving specimens are rare enough today to warrant glass-encased displays.

Physical expressions of such cultural concepts include exhibits of clay unicorns and bronze tortoises sculpted during the Wei (220-265) and Jin (265-420) dynasties, a Jin-era bone ruler and blocks engraved with such motifs as a tiger, a maidservant clasping a spoon and a manservant clutching a broom.

The most invaluable treasures were not just artistic but spiritual.

Buddhism ranks among the most transformative and durable concepts to undertake the eastward pilgrimage along the Silk Road. It not only shaped Dunhuang's society but reshaped the very land itself. The force of faith didn't just move mountains but, in the case of the Mogao Grottoes, reconfigured them.

This cave complex is literally a dream come true. It's said that a monk named Le Zun was enraptured by a vision of 1,000 Buddhas, which inspired him to set a chisel against a cliffside of the Singing Sands Mountain.

Over the following millennium, Dunhuang's devout whittled a honeycomb of over 700 caverns — libraries, temples and galleries — inhabited by statues and murals, embodying a heavenly host in an underground otherworld.

Dunhuang Museum's visitors can step into a reincarnated time capsule — a fullscale replica of Mogao Cave No 45, a cavity crowded with sculptures and frescoes rendered during the Silk Road's Tang-era pinnacle.

Access to the actual cave is restricted, but visitors to this facsimile can linger, explore and photograph its glories uninhibited.

The grottoes' subjects attest to Dunhuang's multiculturalism, as do the diverse currencies that helped finance them.

A numismatic display shows the Arabian gold, Persian silver and Central Asian coins that circulated alongside those from the Han, Jin, Sui, Tang, Song, Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. These coins trace the money trail that maps Dunhuang's path to becoming an international marketplace.

Silent centuries

But Dunhuang's prosperous rise was followed by its decline, and its fortunes scattered like dust in the dry wind.

Following the An Lushan Rebellion in the 700s, the Tubo regime seized control until homegrown hero Zhang Yichao restored Tang rule in 848 AD. In 1036 AD, the Xixia Dynasty captured the corridor.

Though the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) briefly resuscitated trade, the Ming Dynasty eventually lost its grip on the region and sealed the Jiayu Pass in the 16th century, cutting off the last lifeline of its regional rule. An exhibited set of Ming chain mail stands as a silent guardian of the empire's futile attempt to shield its territory's rim.

Water again divined the tides of fate, when the Qilian Mountains' meltwater evaporated, desiccating the lifeblood that had fueled Dunhuang's pulse of commerce and culture. Meanwhile, sea routes became safer and cheaper trade arteries, redirecting the flows of goods from the backs of camels to the bellies of ships.

As commerce and water dried up, Dunhuang's population also withered, abandoning this metropolis to the Taklimakan for centuries.

The curtain fell, and a long intermission began.

Staging an encore

The Qing Dynasty reclaimed territories outside Yumen in the later years of Emperor Kangxi's rule (1661-1722). Dunhuang then slept until 1900, when Taoist priest Wang Yuanlu reawakened worldwide curiosity about these secluded ruins.

He unwittingly thrust the settlement into the global spotlight when he stumbled across the hidden chamber now known as the Library Cave, unearthing a trove of 50,000 manuscripts and paintings. Foreign explorers whisked many of these priceless artifacts overseas soon after.

The museum displays replicas of such scrolls as The Mahaparinirvana Sutra, The Carol of Hundred Thousand Verses and The Lotus Sutra.

This lost-and-found legacy sparked a call to rediscover and recover Dunhuang's heritage, setting the stage for an encore that's winning applause around the world.

ALSO READ: Buddha's gaze into eternity

The museum's concluding displays portray ways that creatives are now bringing Dunhuang's motifs "out of the grottoes" and the past. For instance, they're integrating traditional fresco patterns like the nine-colored deer, thousand-handed Guanyin and triple-hare insignia into innovative designs for modern goods.

They are writing updated scripts for Dunhuang's sequel. They're carrying its Silk Road birthright into our globalized age, ensuring it isn't just inherited across bygone millennia but also by generations yet to come.

And so, the curtain rises again, as the Dunhuang Museum offers front-row seats to what this history means for our future.

Contact the writers at erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn