The Mengdiexuan donations to the Hong Kong Palace Museum illuminate different facets of an open and inclusive ancient China and its ingenious craftspeople. Chitralekha Basu reports in Hong Kong.

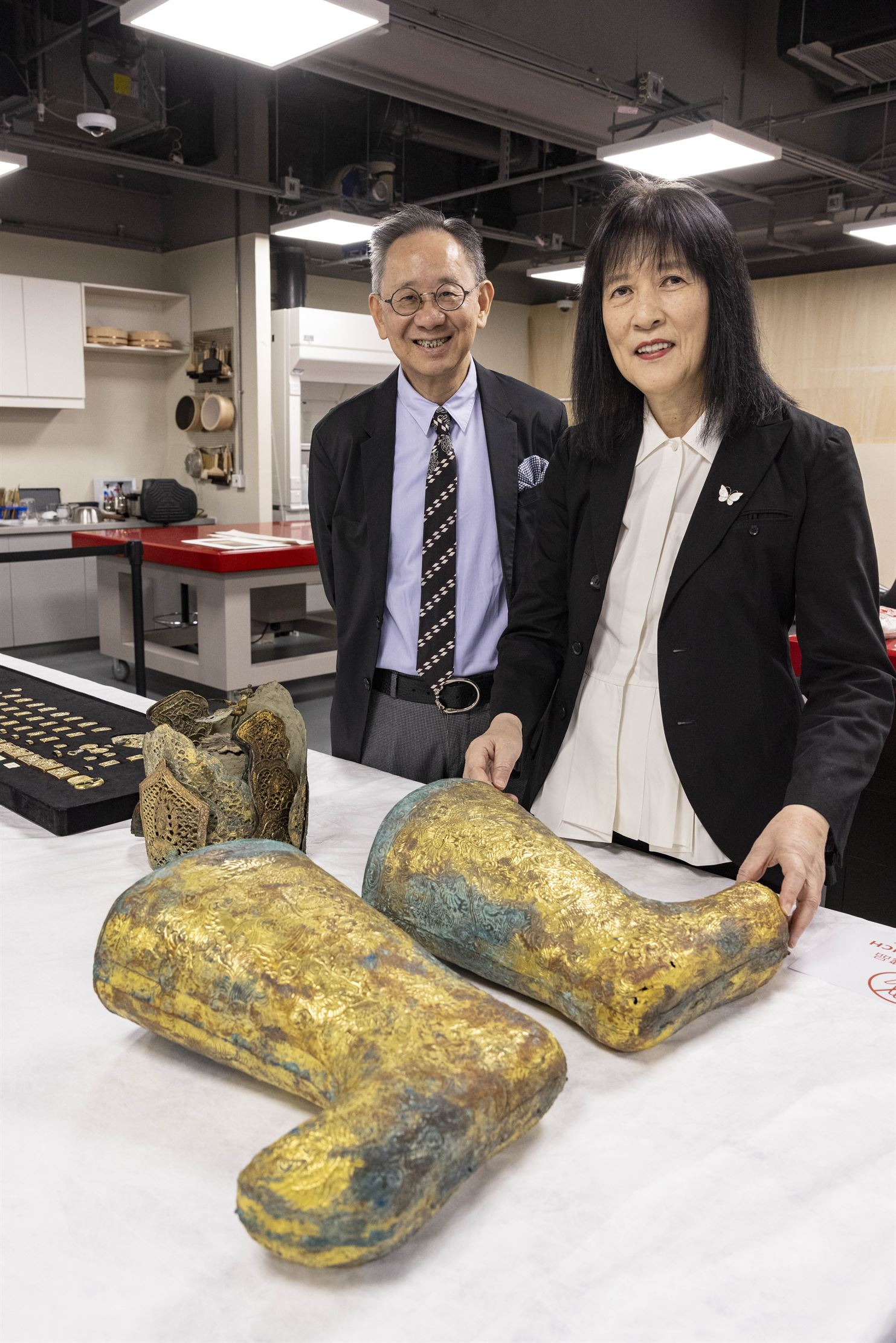

A massive pair of golden boots is among the highlights of the second round of Mengdiexuan donations received recently by the Hong Kong Palace Museum (HKPM). Intriguingly, these gilt copper objects, whose provenance dates back to the Liao Dynasty (916-1125), bear marks of South Asian cultural elements. Their partly patinacoated surfaces reveal intricately hammered images of the makara — a cross between a fish and a crocodile that can be traced back to both Hindu and Buddhist mythologies.

“The makara motifs are an indication of Buddhist cultural influences traveling from India to China,” says Kenneth Chu, one-half of the donating duo. “There are similar religious elements to many of the donated objects,” he says, drawing attention to the floral motifs on the series of gilt silver and gilt bronze belt accessories, also from the Liao Dynasty. “Buddhism was quite a major influence on the northern nomadic people of China at the time.”

READ MORE: Art of gold

There is much more evidence of cross-cultural exchanges among the 417 items that Chu and his wife, Betty Lo — co-owners of the Mengdiexuan Studio collection — have bequeathed to the HKPM, following an earlier donation of 946 objects at the time of the museum’s opening in 2022. For instance, the use of gold and turquoise — inlays in the two ornamental silver hooks that are among the mostrecent donations and belonged to either the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) or Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 8) — is probably owed to China’s nomadic neighbors from the north, i.e., the Eurasian Steppe that would correspond to present-day southern Siberia.

Even before the more-iconic Eurasian trade routes, such as the Silk Road, became operative, “long-distance cultural exchanges between China and Central Asia were taking place in the first millennium BCE,” says Raphael Wong, associate curator at the HKPM. “There were a lot of interactions between China and its neighbors from the north through trading. Some nomads also served as mercenaries in the Chinese armies. There were goldsmiths from among the nomadic communities who settled in China.”

He points out that the hammering technique used to make one of the earliest pieces in the second Mengdiexuan donation — a gold tiger-shaped ornamental plaque (third to first century BC) — is characteristic of the workmanship of the European Steppe, as indeed is the practice of embellishing metal with turquoise inlays.

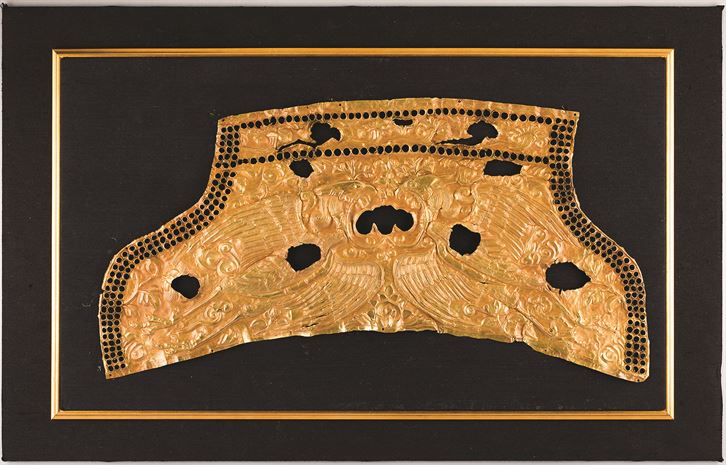

“But later we find turquoise being replaced with semiprecious stones. And that probably indicates interactions between China and Southeast Asia, from where many of these gems were sourced. So we can definitely see an evolution in terms of craftsmanship, techniques and choice of material, over the years,” he says, drawing attention to the intricate filigree work in a gold headgear with images of dragons chasing a pearl and inlaid with rubies, from the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644). The exquisitely crafted piece was part of the first Mengdiexuan donation to the HKPM.

Wong also mentions how the Chinese craftspeople of yore who liberally borrowed techniques from their neighbors across the border were quick to adapt them to suit their own ends. “Once gold was introduced to China — through the interactions between the people of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1126) and the nomadic tribes inhabiting the Eurasian Steppe — Chinese craftsmen started using casts to make gold ornaments. They were already using casts to make bronze ritual vessels for sacrifices, and adapted the technique to make gold ornaments.

Milestones of social progress

The second Mengdiaxuan donation makes the HKPM the custodians of one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of precious metal objects from the Liao Dynasty. The collection demonstrates how the Northern Han — who lived in the region corresponding to present-day Shanxi province — had cross-cultural exchanges with the two major powers of the day: the Liao Dynasty, which ruled over the region to their north; and the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) — which was to their south.

“Our second Mengdiexuan donation has a significant number of pieces that point to a tradition of men wearing accessories,” says Chu. “We find that during the Liao Dynasty, men wore a lot of ornaments — from crowns to earrings to embellished belts.”

He believes both artisans as well as buyers got smarter during the Liao reign. Instead of making objects solely with gold, artisans began combining gold with other metals. Coating bronze, silver and copper with gold and using alloys of gold and copper were also in vogue. In the second Mengdiexuan donation, two pieces of silver saddle ornaments, with gold embossed phoenixes soaring up among the clouds, serve as fine examples of this trend. “The Liao Dynasty people would sometimes add gold elements to or gild a piece of silver to add value,” says Chu. However, sometimes such decisions were taken to cut down on the manufacturing costs, he adds.

READ MORE: The Sanxingdui connection

He contends that the practice of wearing gold in combination with organic material is also an indicator of an evolving society. The elaborate belt that was once embellished with a series of small golden rectangles with floral patterns was probably made out of leather, with tassels hanging from it. “From this piece, it’s evident that Liao society had evolved from wearing all-metal girdles to gold in combination with other material.”

When studied chronologically, the Mengdiexuan objects also demonstrate a progress from functional items — hooks and saddles — to purely decorative ones like hairpins. However, one of the later pieces in the collection, a gold cape weight with exquisitely carved crane and stag motifs from the Southern Song period (1127-1279), meant to hold flowing outerwear in place, fulfills both tasks.

“It’s a very interesting invention,” says Wong. “If you look at pieces from the Tubo period (seventh to ninth century), they are decorated with mythical animals common to Western and Central Asia, whereas the cape weight has images of a crane and a stag that are more realistic.”

Passing the baton

Chu and Lo call themselves the temporary custodians of the Mengdiexuan collection. “These precious metal craft from the ancient times are a very important part of the Chinese material culture,” says Lo. She is especially keen that the extensive research the couple had conducted on the subject should continue under the aegis of the HKPM.

The donors have complete confidence in the museum’s conservation team. “We don’t necessarily want them to scrape the patina off the boots,” Lo says, stressing on the importance of not losing sight of the historical context of a piece when the museum puts it on display. “We need the conservationists to handle the objects with a passion, have an understanding of the extent to which a piece could actually be conserved. I’d like them to respect the fact that these are relics, not commodities on sale.”

ALSO READ: Experts: HKPM to convey motherland's history to world

For Chu, the value of the Mengdiexuan objects lies in what they reveal about Chinese social history. “I think these objects are a reflection of the accommodating nature of Chinese society,” he says. “The Hans co-existed with different ethnic groups. The peaceful neighborly relations between the Liao and the Northern Song people show that Chinese society was already quite pluralistic in the 10th century. I think this is the reason why Chinese people from different corners of such a vast country are ready to accommodate each other. We integrate with others quite easily. So this collection tells a very good story.”

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com