Master artisans dedicated to a craft established deep in the national psyche, Zhao Xu reports.

Editor's note: Traditional arts and crafts are supreme samples of Chinese cultural heritage. China Daily is publishing this series to show how master artisans are using dedication and innovation to inject new life into heritage. In this installment, we delve into the cultural roots of folding fans.

Nearly three decades have passed, but 57-year-old Xu Jiadong still remembers the day when he first went into a bamboo forest with his father to "handpick the ones that he would later use to make the ribs of folding fans".

It was in early January in Anji county of eastern China's Zhejiang province, where a special type of bamboo known as yu zhu, or "jade bamboo", grows in abundance.

That's where Xu, then in his late 20s, was given lessons by the old man while breathing in the chilly mountain air.

READ MORE: Making ancient art relevant for modern audiences

"For the purpose of fan-making, bamboo can neither be too young nor too old — it has to be big and sturdy enough while at the same time fine-textured. Generally speaking, plants that have grown to 5 years old are the most desirable," Xu says.

"One thing my father always asked me to look for was the natural layer of white, waxy substance coating the plant."

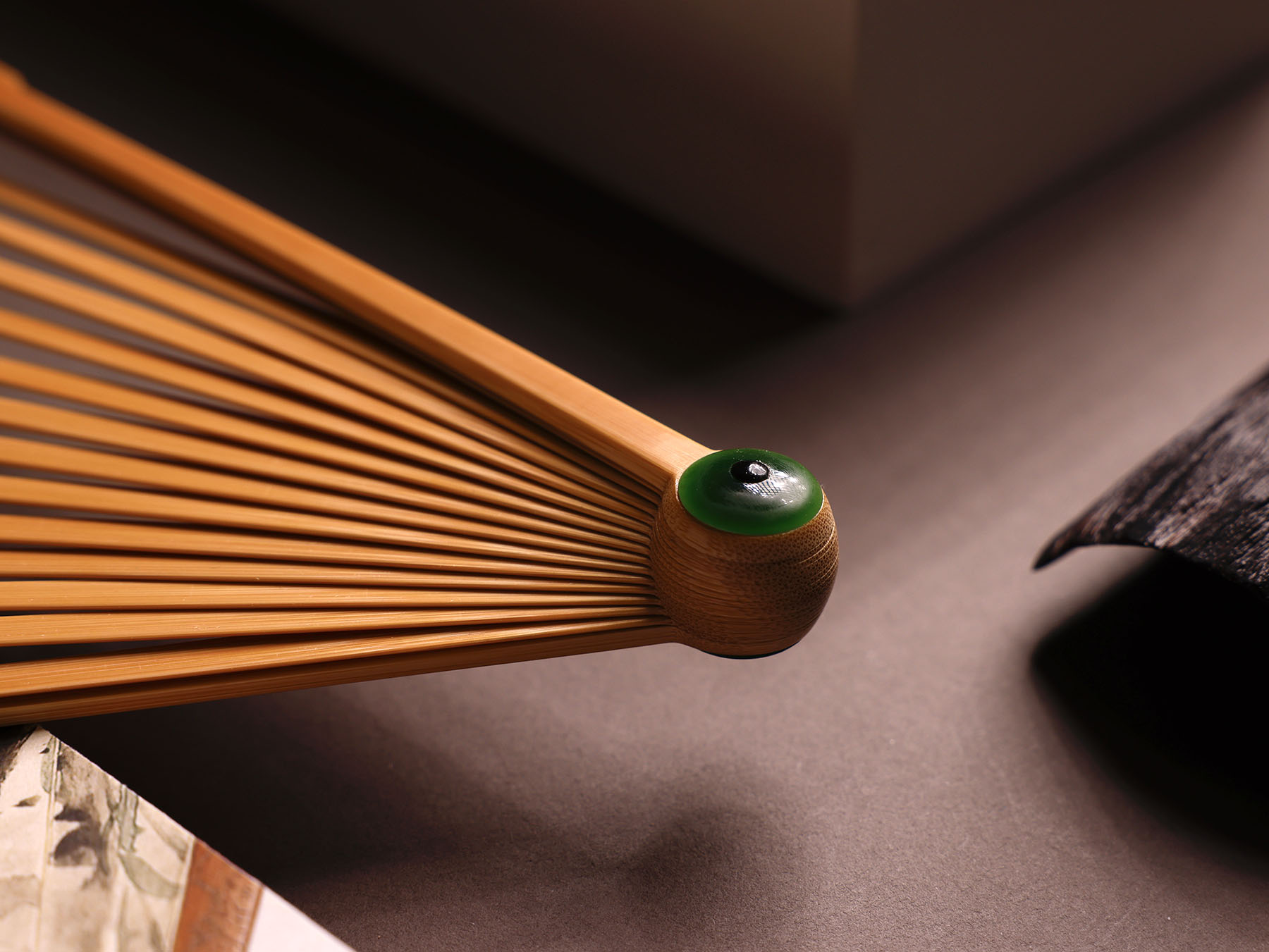

This is bamboo wax, and when scraped off, the green color underneath is revealed — thus it's known as "jade bamboo". The wax shields the plant from excessive moisture loss and pests, giving it a smooth, suave quality long admired by Chinese fan-makers including Xu and his father.

"Artists from ancient China, especially those living in turbulent times, often painted wind-swept or rain-slashed bamboo plants, inspired equally by their unbreakability and flexibility," says Wang Yimin, an ancient Chinese painting expert from Beijing's Palace Museum.

"It's also worth noting that jie, the Chinese character for bamboo nodes, also means integrity and rectitude."

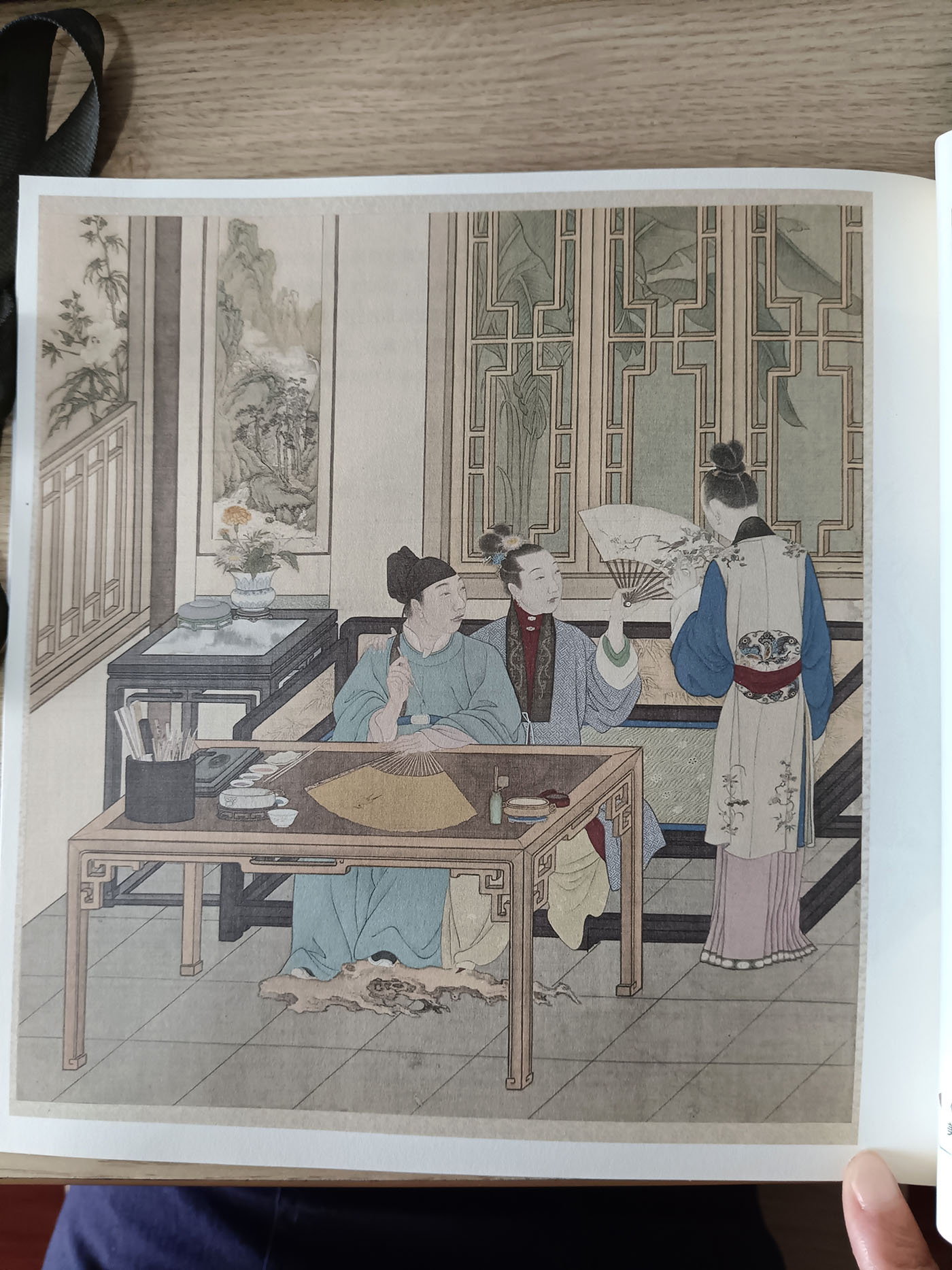

By the time the folding fan became popular in the country in the 14th century, bamboo had long entered the Chinese visual and literary iconography, a powerful symbol for those who would like to think of themselves as men of virtue.

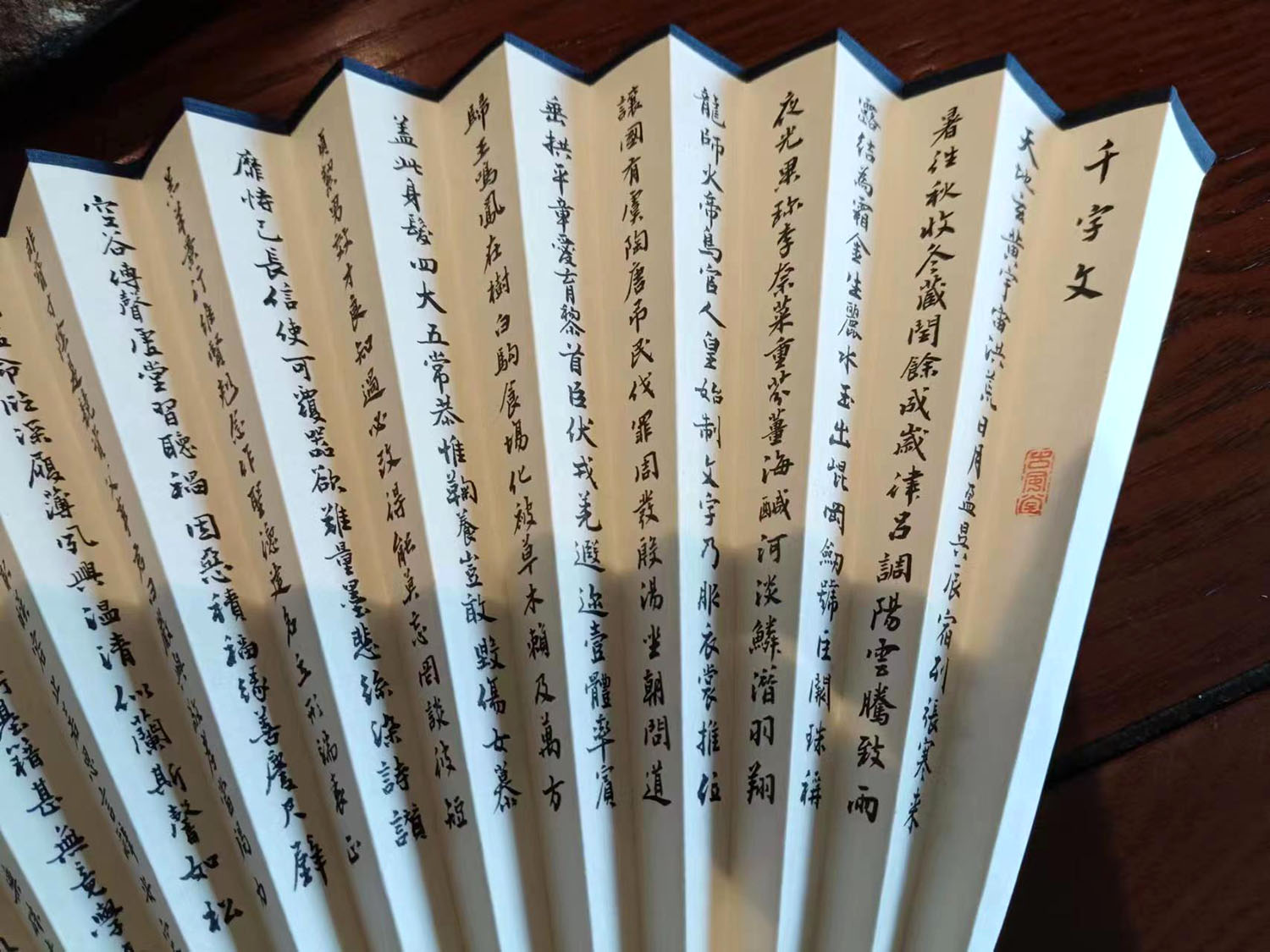

"Fans made of sandalwood or ivory may be called rare or valuable, but they are nowhere near elegant, and therefore, not for one who's aesthetically cultivated," according to Shen Defu, a man of words who lived between the 16th and 17th centuries.

Precision and spontaneity

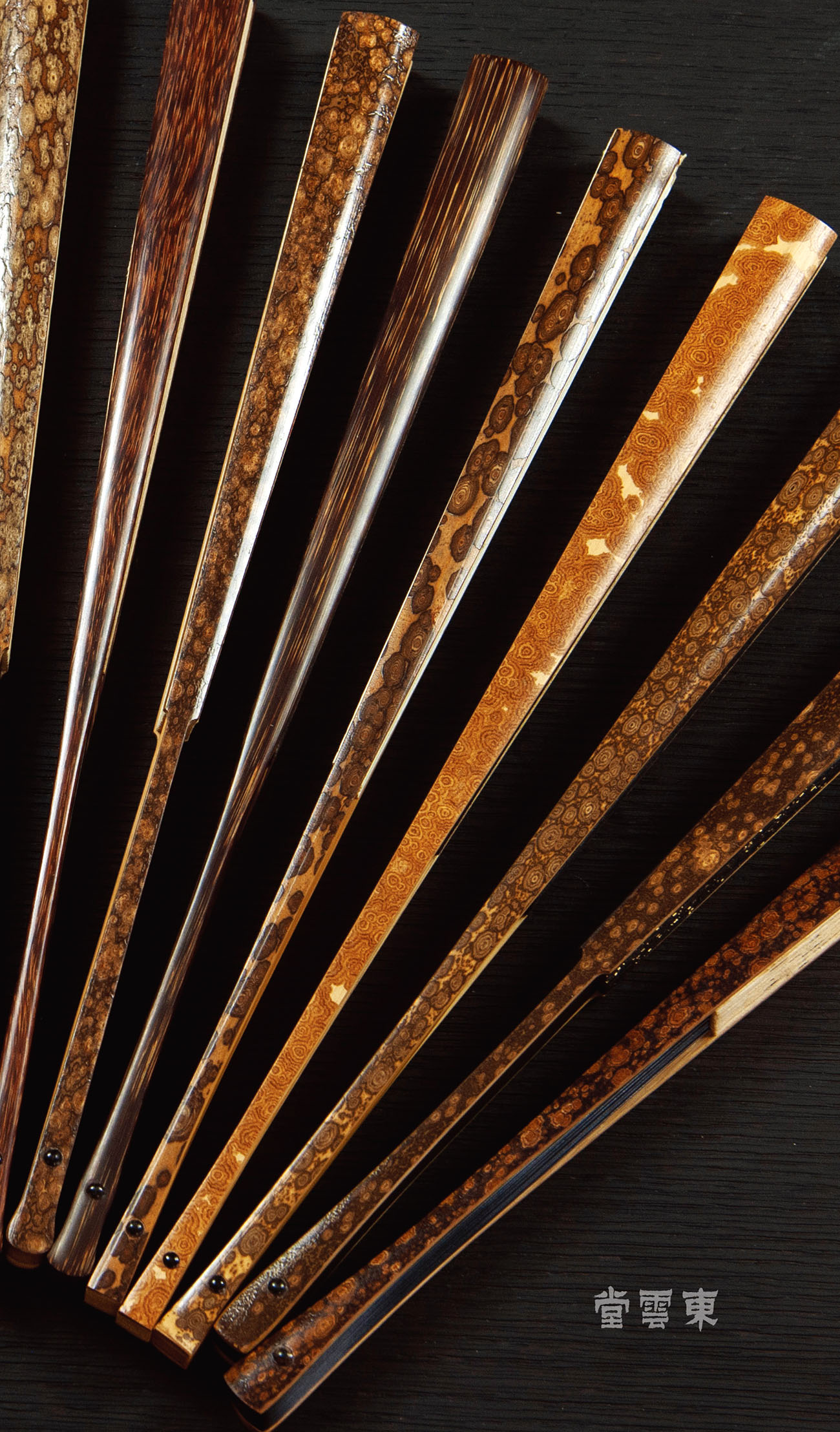

Aesthetic sophistication — it's in that indefinable, even unfathomable, concept that Xu's ultimate challenge lies. "It's all there in the lines and in each and every turn — some rather abrupt, some so gentle that they are hardly perceptible — that the lines took," says Xu, celebrated today as one of the country's best makers of folding fan ribs.

"As long as you get graceful lines, you get graceful forms."

That gracefulness is best appreciated when a folding fan is folded, with two pieces of bamboo slips holding the entire fan together. As these two pieces taper down from top to bottom, they follow distinct curves in designs named beautifully and evocatively — "the shoulder of a beauty", for example.

Typically, these two pieces — dubbed "the main ribs" as compared to the "minor ones" in between them — would fan out a little toward the very end. "Swallowtail" is the name assigned to one specific type of design concerning this end part.

"Controlled spontaneity" is how Wu Jiajun, a pharmaceutical salesman who has been training with Xu during his spare time for the past three years, describes "what it takes to produce that level of artistry that my teacher has arrived at".

"Having the good luck to observe the master while he's at work, I realized that more often than not, the contour of a 'main rib' is decided within a few applications of the carving knife — there's only one knife for the entire process," Wu says.

"Sometimes, the knife would glide through the material in an extended motion; other times, it makes quick, decisive cuts. Either way, there would be absolutely no repeat of the same movement. One has the feeling that the master, guided by his own instinct, always gets to say what he has intended to say with just one fluid and resolute stroke of the knife."

In that sense, there's not much difference between carving the fan ribs and painting a fan. The latter, done in classical Chinese style with an ink brush, is also characterized by a combination of precision and spontaneity.

"One thing my father taught me was to think of the knife as a brush," Xu says.

"In fan-making, polishing is routinely done to the carved ribs, but my father often reminded me not to overdo it. 'Don't gloss away all the traces of your knife', he would say. 'Because they are indicators of an authentic work of art'."

A portable piece of art

It's fair to say that a beautiful set of fan ribs takes the work of both man and nature. While the monochromatic "jade bamboo" (also known as mao zhu or tortoiseshell bamboo) exudes an understated elegance, other types favored by fan-makers feature naturally formed patterns that have been compared, among other things, to spots carried by sika deer, a species native to East Asia.

"In Chinese, we call the deer meihua lu, or 'the plum-blossom deer', and the bamboo 'plum-deer bamboo'," says Xu, pointing out that the unique pattern has formed on the plant as a result of microorganism infection.

For those in the know, the plum tree, which typically goes into bloom during winter, is one of "the four noble plants" in Chinese culture — the other three being the bamboo, the chrysanthemum and the orchid. A standard subject for literati painters — those with a high level of education — from ancient China, all four make frequent appearances on the fan surface both then and now.

"Literati culture, which was fostered by the educated elite of ancient Chinese society, had for more than a millennium exerted a major influence on Chinese art-making," says Wang from the Palace Museum.

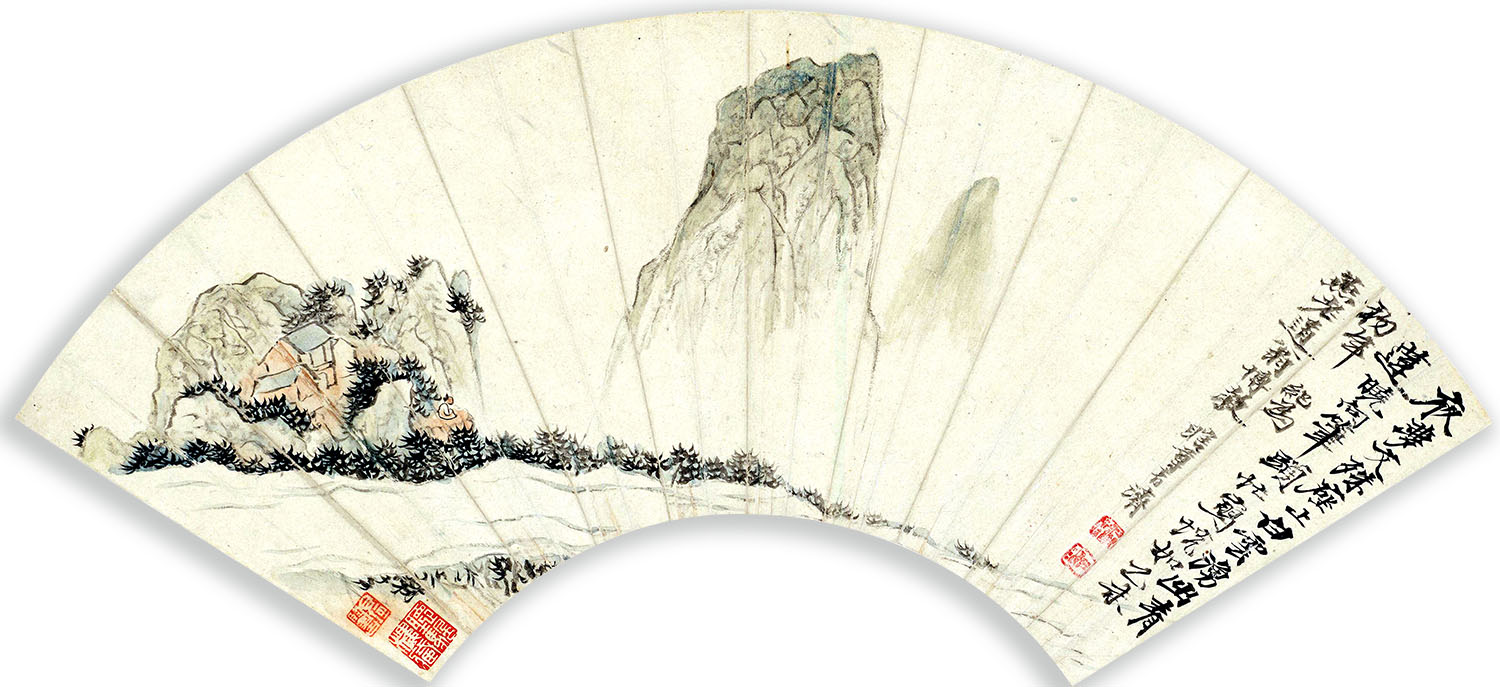

"It was only with an understanding of that, can one begin to see the Chinese folding fan not just as something to drive away the summer heat, but a portable piece of art, almost every detail of which is dictated by the sensibilities of the literati group."

Ironically, although the fan ribs are essential parts of a fan, for many years in the 20th century, they had been overlooked, taken out and thrown away by antique dealers who would only keep the painted fan surface.

"That situation has completely changed over the past decades. The art and antique market has taught everyone a lesson as to the aesthetic and financial value of handcrafted fan ribs, both old and new," says Xu.

Both Xu's and his father's creations had been sold at auctions for prices between 30,000 to 200,000 yuan ($4,140-$27,600).

Xu's father first learned to make fan ribs in the mid-1940s when he was around 15. And he did so as an apprentice in a fan-making workshop in Suzhou — there were about 40 to 60 in the city in those days, says Xu.

His studio's rear window opens up to one of the numerous canals, which the eastern Chinese city in Jiangsu province has been known for throughout history.

"Historically, 'made-in-Suzhou' had been a brand name of its own, denoting consummate craftsmanship infused with the region's longstanding tradition of literati culture," says Xu.

"Over centuries, the folding fans produced by the Suzhou artist-artisans had traveled the waterways between the city and the rest of China, where they commanded their followings."

The old man, who brought his son into the world of fan-making when the latter was 20, continued to make fans until his own passing in 2020 at the age of 87.

"What my father always insisted on doing as a fan-maker was to do it all by himself, which is rare these days since most masters would delegate part of the job to an apprentice," Xu says. "Personal involvement in every step of the fan-making process allows one to carry on his aesthetics."

That process starts with the selection of bamboo, something Xu still does every January in Anji county.

ALSO READ: Following the patterns of history

"The bamboo plants I have chosen are boiled to prevent parasites, before they are sun-dried and stored in my studio, for another five years," says Xu. "That's the amount of time needed for the material to contract gradually so that there will be no tiny cracks on the fan ribs that would eventually come out of them.

"But bamboo, even in the form of a fan, will never stop aging, sometimes taking on slightly darker colors.

"All one ever needs to feel its story is to hold it in hands."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn