A 93-year-old recalls spending her childhood with her father protecting the Mogao grottoes to highlight their legacy with the world, Lin Qi reports.

Recalling her bittersweet experiences during her teen years in Dunhuang, Gansu province, 93-year-old Chang Shana can't help but smile while remembering those days. She was 12 when she arrived in Dunhuang in the 1940s. Her father, Chang Shuhong (1904-94), the founding director of the Dunhuang Academy, committed his life to the protection and conservation of the caves and the art inside.

The young girl endured harsh living conditions in the desert while working with her father to copy the murals and Buddhist statues in the Mogao Caves, and forged a lifelong love of Dunhuang that has lasted for several decades until now, through her paintings and design.

Many people said, you are elderly, and you should no longer make yourself busy with things. I always keep in mind father’s wishes to carry on the Dunhuang heritage, and for that reason, I always feel energetic.

Chang Shana, 93, artist

"Dunhuang is my hometown. Father often said, 'Shana, don't forget you are from Dunhuang'."

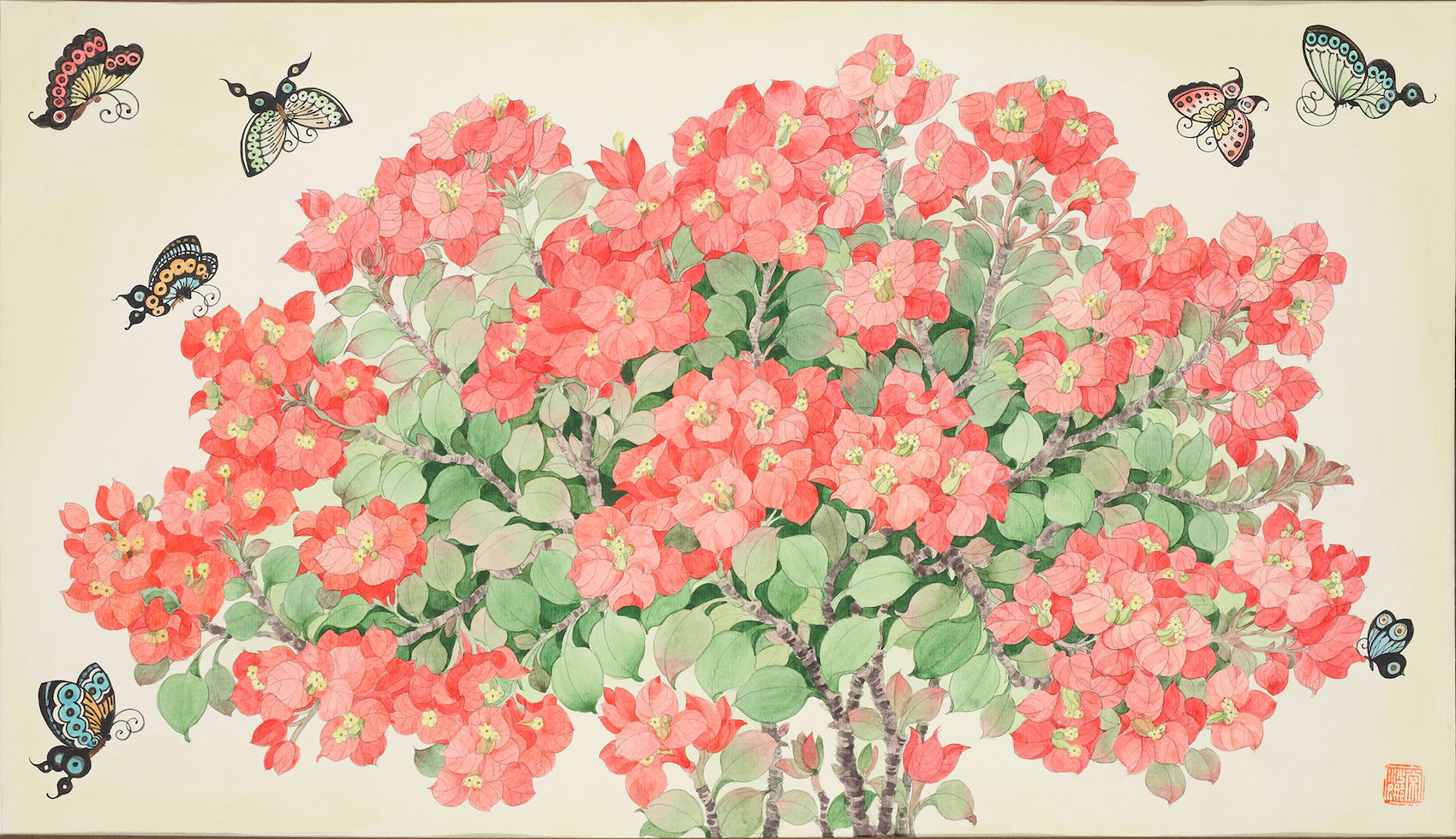

In 2014, Chang Shana, a prominent designer and scholar of Dunhuang art, initiated a touring exhibition titled Everlasting Beauty of Dunhuang. Since premiering at Beijing's Today Art Museum, the show of works, created by her and her father that are inspired by Dunhuang's immense artistic trove, has since traveled around the country, raising awareness of the importance of protecting Dunhuang's legacy.

READ MORE: Forging a creative time

It recently returned to the capital, with its latest installment running at the Chinese Traditional Culture Museum until Oct 27.

From Paris to promises

The exhibition pays tribute to a family passing on a mission from father to daughter over more than eight decades. The journey began when Chang Shuhong decided to leave behind a Parisian life with good prospects to head toward a dream and mission — and, of course, uncertainties — back in his home country.

He graduated from the well-known Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts and won prizes at the prestigious Paris Salon.

He would have pursued his potential as a career artist if he had not picked up Paul Pelliot's Catalog of Dunhuang Caves at a street stand selling books on an autumn day in 1935. It contained six volumes featuring photos of over 300 murals and figurines to reveal a remarkable trove of art and cultural exchanges that spanned a millennium.

Many years later, Chang Shuhong recalls feeling awe at seeing those vivid details in the books that revealed a history of his homeland he had not known before.

"The strokes (in the murals) were powerful, even bolder than that of the works of Fauvism, the structures rendered a feeling of magnificence, and the figures being depicted looked alive and energetic," he once said.

A later visit to the Guimet Museum where he saw cultural objects plundered from Dunhuang by Western explorers further intensified his wish to return to unveil Dunhuang's mysteries to the world.

Chang Shana was born in Lyon and lived in Paris until she was 6.Her family returned to China amid the chaos of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45). They first settled in Chongqing, where she attended primary school — she still remembers some of the local dialect. At the end of 1943, she arrived at Dunhuang after a long, bumpy voyage with frequent layovers and transfers.

She was impressed by the harsh natural environment of the desert there — often harassed by sands and gales. Material comforts were scarce. This was perhaps ironic, considering Dunhuang's legacy as an oasis of art and cultural exchanges along the ancient Silk Road.

She says she'll never forget the first meal she had in Dunhuang: a bowl of noodles with salt and vinegar.

"I remember I then asked, 'How come there is no meat or vegetables?' And, Dad, looking a bit embarrassed, said: 'It's late. There will be mutton tomorrow.' I later realized that was unlikely because there was nothing out there," she recalls.

"To make our life better, my father tried to plant flowers and grow vegetables. He worked really hard."

Yet, Dunhuang did nurture the little girl, in a different way. "The moment I entered the caves, I was dazzled. The caves had no doors and faced east to allow the sunlight in. I had never seen so many murals and statues, bright in color and all over the grottoes," she says.

She then followed in the footsteps of her father and other artists working in the caves. She followed their instructions to also copy the beautiful wall paintings and figurines from different periods of time.

Her daily routine also included practicing calligraphy, learning French, studying Chinese and taking lessons in Chinese and Western art history, taught by artists who worked with her father researching Dunhuang.

"There, I completed the first stage of education in my art career, although without a diploma," Chang Shana says.

Several large copies of jingbian, or sutra depictions, on the walls from the 1940s are on show to offer a glimpse of the solid training she received and the understanding of Dunhuang she accumulated, says her son, Cui Donghui, who's deputy director of the School of Architecture of the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

"The basic skills she grasped while copying allowed her to understand the compositions and the relations among the figures in the murals," Cui says.

Design for China

At 17, she went to study art and museology in Boston, the United States, for two years. She returned at the end of 1950 to assist her father in staging an exhibition of Dunhuang art at the Palace Museum, where their copies of murals and statues were also displayed.

The works caught the attention of noted architects and scholars Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin.

Touched by Chang Shana's gift and devotion to Dunhuang, Lin helped her land a job as an assistant lecturer at the architecture department of Tsinghua University.

Lin hoped to introduce the young girl to the fields of design and education, where she would develop new ways to keep alive the heritage of Dunhuang and other traditional art.

Lin was one of the key influences on Chang Shana, who inspired her to integrate Dunhuang elements into many aspects of life. Lin took her to factories that made enamelware and porcelain to get inspiration about new ways to give traditional arts and crafts a modern uplift.

"Lin said you need to make people feel, and live with, the beauty of tradition," Chang Shana says.

Chang Shana later taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and the Central Academy of Arts and Design, now the Academy of Arts and Design of Tsinghua University.

As a designer and design educator, she participated in several national projects in which she incorporated the motifs and patterns from the murals, architecture and Buddhist caves that enriched her teen years.

She designed silk scarves featuring zaojing (caisson ceiling) patterns from Dunhuang and white doves, which were chosen as gifts to international delegations attending a conference in Beijing in 1952.

Years later, she became a member of the design team for the interior decoration of the Great Hall of the People, during which time she learned to go beyond aesthetics to also consider other factors such as function and materials.

Decades afterward, she incorporated Dunhuang art into her designs at several landmark venues in Beijing, including the Cultural Palace of Nationalities and the Capital Theater. The Everlasting Beauty of Dunhuang exhibition has been her latest effort to carry on her father's commitment.

ALSO READ: Masters in their prime

She recalls the time when she launched the touring exhibition a decade ago. "Many people said, you are elderly, and you should no longer make yourself busy with things. I always keep in mind father's wishes to carry on the Dunhuang heritage, and for that reason, I always feel energetic," she says.

"The exhibition has toured dozens of cities, and I will keep promoting Dunhuang art as long as I can walk and talk. It is a tribute to my father and my mentor, Lin Huiyin, especially in this year that marks the 120th anniversary of both of their births."

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn