Exhibition of early modern Chinese design reflects both history and the change and dynamism of the era, Lin Qi reports.

Is there a link between Ming-style furniture and the sedan car? The idea is improbable, or so it may seem at first. After all, Ming-style furniture dates back to the dynasty that ruled between 1368 and 1644, appearing centuries before the automobile, and is known for its minimalist design, the result of collaboration between intellectuals and master craftsmen, use of precious hardwoods and mortise-and-tenon joinery.

But when Jia Yanliang was assigned to design a prototype for Hongqi (Red Flag), China's best-known domestic automobile brand, at the First Automobile Works in Changchun, Jilin province, in the 1960s, the then 24-year-old turned to the simple, neat lines of Ming-style furniture as a reference when it came to the now iconic CA770 sedan.

Jia's integration of the structural beauty of Ming-style furniture with the design of modern vehicles can be traced to his work as a student at the Central Academy of Arts and Design, today's Academy of Arts and Design, at Tsinghua University.

A design for a sedan he drew in 1959 hints at the solemnity of classical Chinese architecture and furniture, as well as what he later described as "a sense of forward motion".

The drawing is one of more than 200 paintings, posters, photos, documents, publications and other historical materials on display at The Sources of Contemporary Design in China, an exhibition at the Art Museum of Central Academy of Fine Arts, which runs through to April 21.

The exhibition focuses on painting an overall picture of Chinese design — including graphic, industrial and urban planning — between 1945 and 1959, a period of dramatic social change in which artists and designers like Jia started revolutions, and their work, under the banner of "Chinese style", helped usher the country into industrialization.

Jin Jun, director of the CAFA art museum and the exhibition's academic host, says that in a profound way, the exhibits reflect the social and cultural scene spanning the 15 years before and after the founding of People's Republic of China in 1949, from the perspective of design.

"From books and clothes to cars, these excellent designs were used in both daily life and industry, and played a vital role in the course of modernization," Jin says.

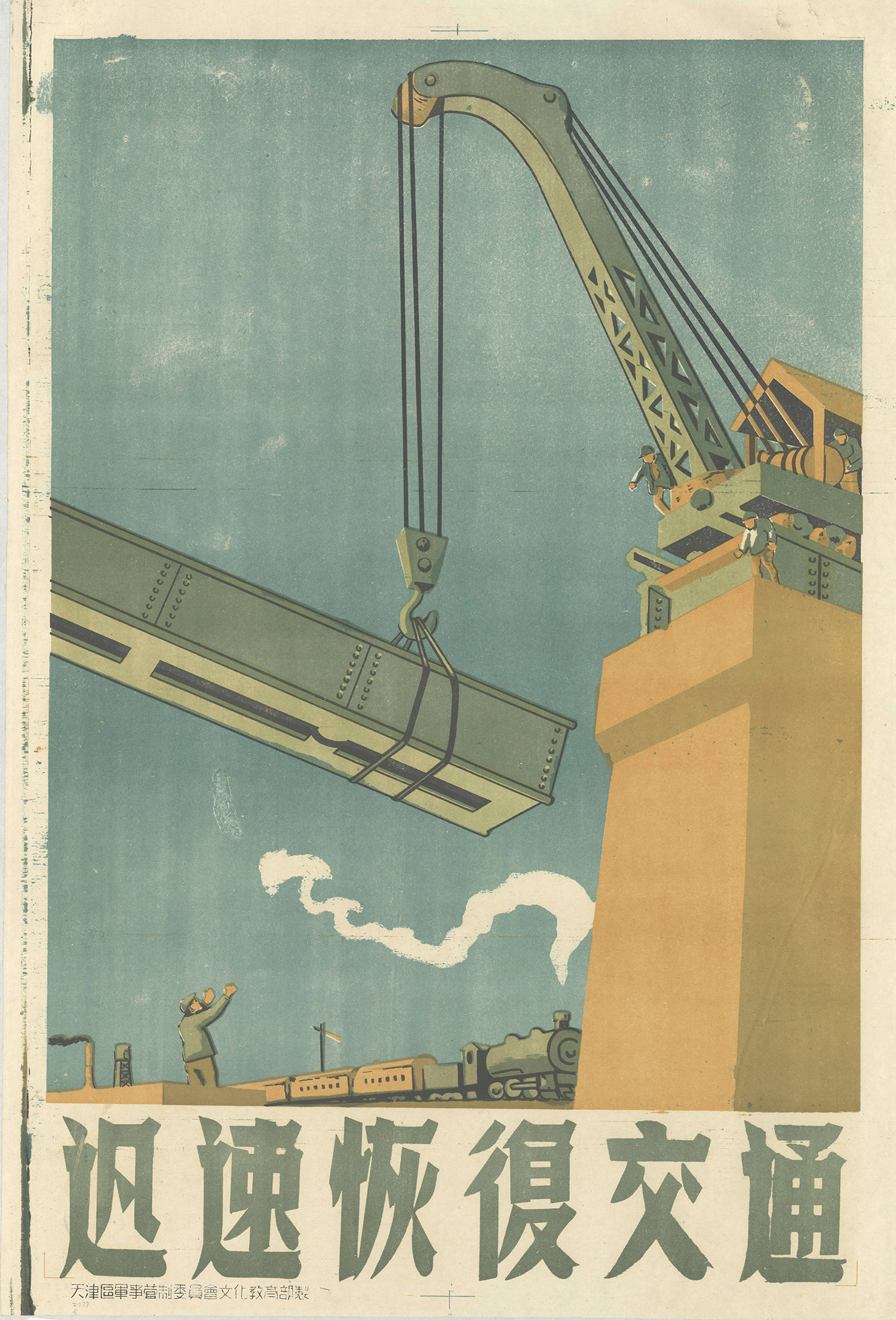

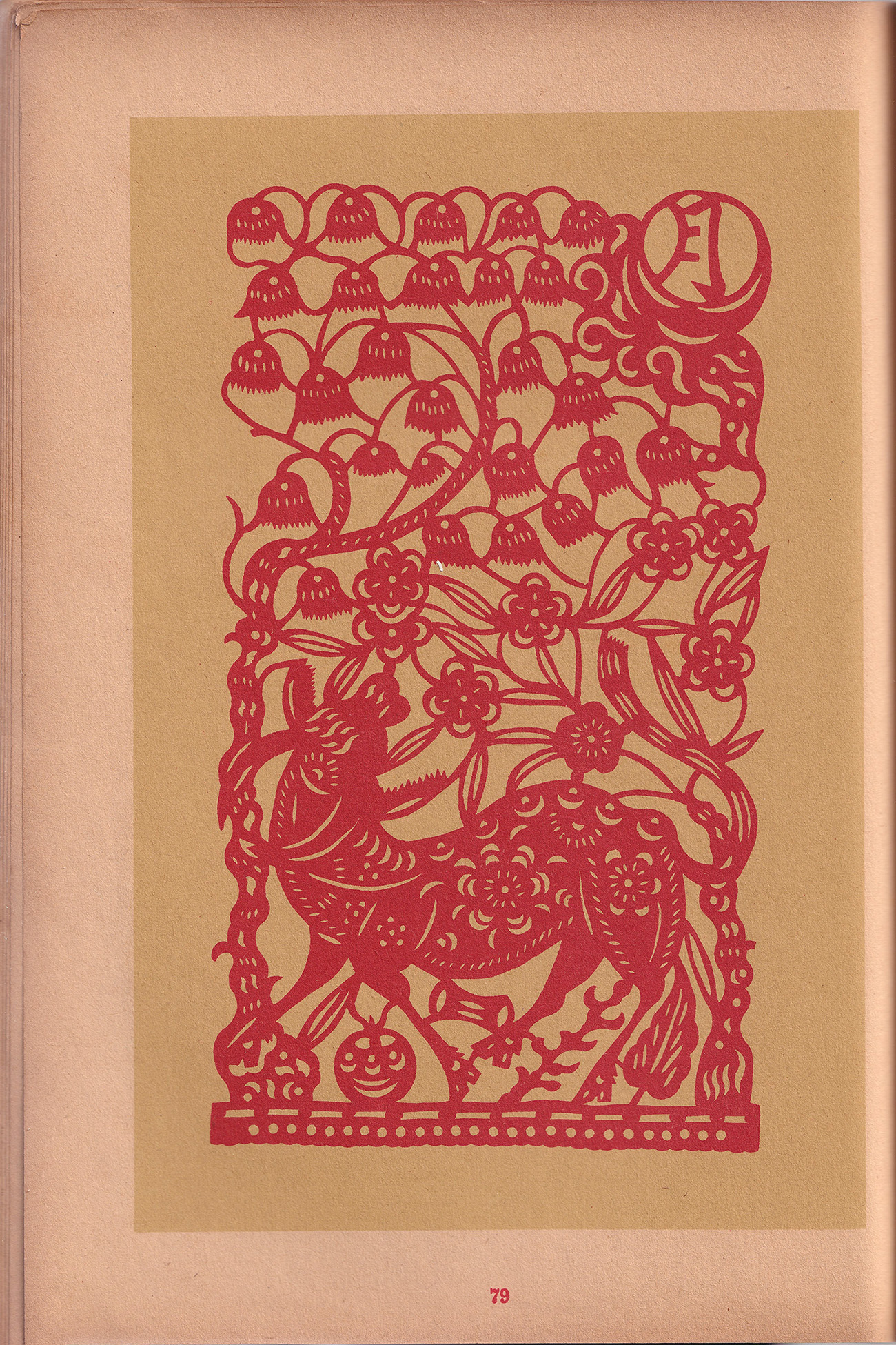

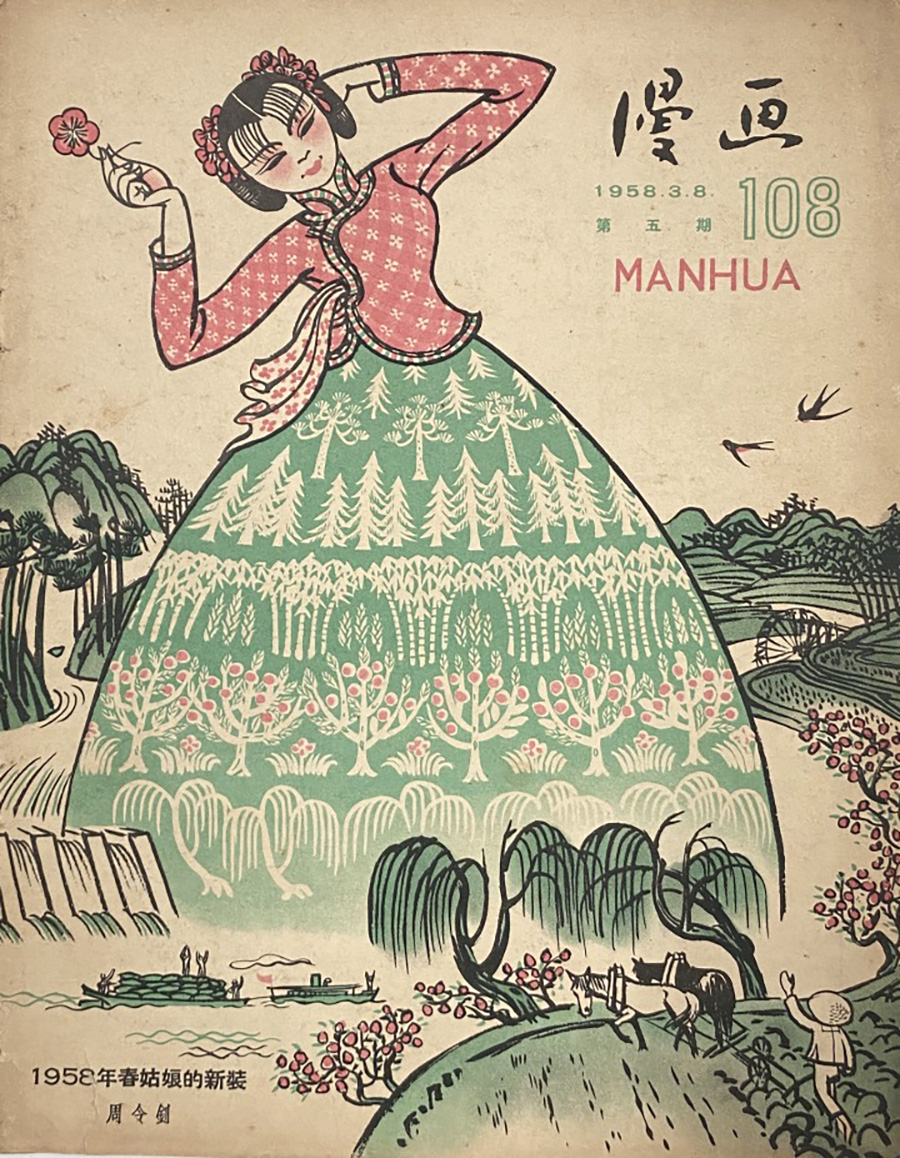

The exhibition begins with the review of design in the second half of the 1940s. Triumphant following the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), China was at the dawn of embracing a new era. In liberated areas, artists under the leadership of the Communist Party of China used forms of folk art, such as nianhua (New Year paintings), to design posters promoting revolutionary ideas. In other parts of the country, the recovery of industry and commerce gave rise to a group of designers who embraced modernist ideas and designed in tune with global trends. The exhibition's juxtaposition of the work of these two groups demonstrates the diversity in design and the cultural vigor of the time.

Over time, their accumulation of knowledge and experience greatly contributed to social and industrial developments in the years following 1949.Examples vividly displayed at the exhibition range from the national flag and emblem, landmark buildings like the Beijing Exhibition Center and domestic brands like Hongqi automobiles, to items of daily use such as qipao (cheongsam) dresses and textile patterns.

Hao Ninghui, dean of the School of Design at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, says that the meaning of these designs lies in not only their innovative forms, but also in their embodiment of a cultural identity and recognition of Chinese cultural values, which blends elements of traditional arts and crafts in a harmonious way.

Examples of note include designs by Chang Shana, the respected scholar of Dunhuang art, for the ceiling decorations of the banquet hall at the Great Hall of the People and for a silk scarf, both done in the 1950s, which incorporate symmetric, decorative motifs taken from the Dunhuang murals in Gansu province.

Chang spent her teenage years in Dunhuang, where her father founded and served as the first director of the Dunhuang Academy. She was later introduced to design in Beijing by Lin Huiyin, a reputed architect, and became her assistant at Tsinghua University in the early 1950s.

Chang once said that one important lesson she learned from Lin was to give ancient arts and crafts, like Dunhuang art and the jingtailan enamel tradition, a modern revival by integrating them into people's lives.

With Lin's words in mind, Chang created pieces that ornamented architecture in Beijing, and were given as gifts to international visitors.

Hao says that as their predecessors did decades ago, designers today also undertake dual tasks, "on one hand, studying the history of Chinese design and underlying cultural traditions, on the other hand, participating in global exchange to bring Chinese design to the world stage".

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn