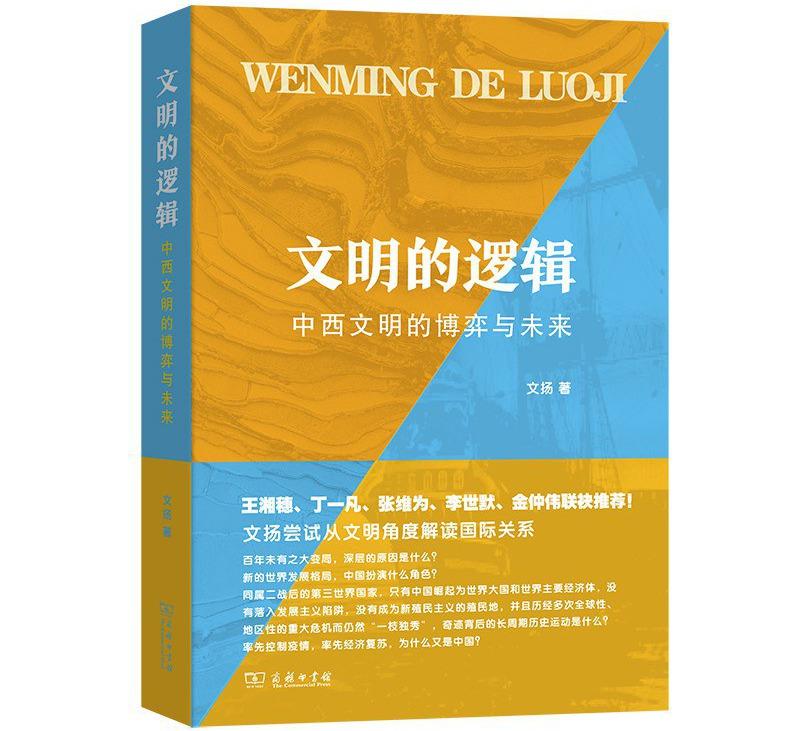

Professor Wen Yang’s new book, The Logic of Civilization: The Interaction and Evolution of Chinese and Western Civilization. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Professor Wen Yang’s new book, The Logic of Civilization: The Interaction and Evolution of Chinese and Western Civilization. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

China’s 5,000-year-old civilization cannot be understood by Western criteria, nor can it be judged by Western standards, according to Professor Wen Yang. Rather, the Chinese civilization is a phenomenon sui generis with its own history, logic, and self-understanding, he writes in his new book, The Logic of Civilization: The Interaction and Evolution of Chinese and Western Civilization.

The differences between China and the West are so deep that Westerners fathom them with great difficulty. To Westerners, civilization simply is Western civilization, the progeny of Greek philosophy, Roman Law and Hebrew revelation. China, the world’s most populous country and until the late 18th century by far the wealthiest, is regarded as an anomalous backwater, the domain of an unchanging “oriental despotism” in a view promulgated by Western thinkers as diverse as Montesquieu, Hegel and John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx. As historian Ram Sharan Sharma wrote, “Evidently the idea of oriental despotism coupled with that of the unchanging character of the East infected not only the western orientalists of the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but also Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.”

An exception was the 17th century polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the inventor of the Calculus as well as the binary computer. He saw in China’s written ideograms an exemplar for his universal characteristic, a system of signs that unite language and mathematics, including a semantic as well as a syntactical function: “One could perhaps one day adapt these characters not only to represent as the ordinary characters do, but also to calculate and aid imagination and meditation.” Leibniz saw in Chinese culture a form of linguistic universalism absent in the West, in a language that represented ideas directly, rather than representing sounds which represented ideas.

But Leibniz was an exception among Western thinkers. Twentieth-century America’s view of China bore the stamp of Christian missionaries who saw in China the world’s largest reserve of souls requiring salvation. The US project of propagating US democracy throughout the world associated with President Woodrow Wilson found its Chinese expression in the Christian missionaries who dominated US policy-making for East Asia. In a secular form, this Protestant perspective on China transmuted into a consensus US view that as China became more prosperous in the early years of the 21st century, its political system would evolve to resemble that of the United States. US disappointment about China’s failure to meet US expectations is an important source of Sino-US friction today.

Professor Wen Yang, a researcher with the China Institute, Fudan University, and author of The Logic of Civilization: The Interaction and Evolution of Chinese and Western Civilization. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Professor Wen Yang, a researcher with the China Institute, Fudan University, and author of The Logic of Civilization: The Interaction and Evolution of Chinese and Western Civilization. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

One of China’s leading theorists of civilization and columnist, Prof. Wen proposes a diametrically opposite view: Civilization is not a Western matter but first and foremost a Chinese one. Chinese civilization has endured for 5,000 years; by contrast the Western nation-states began to form in embryo slightly more than a thousand years ago when barbarian invaders met the surviving remnants of the Roman Empire. The legal foundation of the Western nation-state did not take shape until the Treaty of Westphalia half a millennium ago. To identify civilizational history with Western history, Wen writes, ignores the duration and continuity of Chinese civilization over a much longer time frame.

The evidence for the continuity of Chinese civilization is not in question. We know from archaeological investigation that large-scale flood control infrastructure was built in the Yellow River Valley 5,000 years ago. The Qin Dynasty’s 2,300-year-old infrastructure for flood control, irrigation and river transport remains in active use. The definitive technologies of the early Industrial Revolution, including movable type, the forced-air steel furnace, the clock, gunpowder and the magnetic compass came to Europe from China. The most characteristic feature of Chinese governance, the Imperial civil service examination, dates back in its earliest form to the Wei Kingdom during the Warring States period and was fully developed in the Tang Dynasty.

Ding Yifan, a professor at the World Development Institute of the Development Research Center of the State Council observed in a review of Prof. Wen’s book: "The starting point of Wen Yang's civilization theory is the proposition of 'civilization as a Chinese problem' for the long-existing and continuous Chinese civilization. It overturns the theoretical cornerstone of 'civilization as a Western problem' long constructed by Western scholars and Western media, and reinvents the previous academic tradition of equating 'civilizational history' almost with Western history and ignoring or disregarding the achievements of non-Western civilizations."

Westerners will find Prof. Wen’s thesis challenging. The West’s own generative principle since it first emerged out of the ruins of the Roman Empire is universalist, and the notion that radically different modes of civilization exist runs counter to Western self-understanding. In quite a different way, China’s civilization is universalist as well.

Folk artists perform during the opening ceremony of the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) in Kunming, Southwest China's Yunnan province, on Oct 11, 2021. According to Prof Wen, the different paths of China and Europe in uniting people of many languages are noteworthy. (Chen Yehua / Xinhua)

Folk artists perform during the opening ceremony of the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) in Kunming, Southwest China's Yunnan province, on Oct 11, 2021. According to Prof Wen, the different paths of China and Europe in uniting people of many languages are noteworthy. (Chen Yehua / Xinhua)

All civilizations begin with the problem of integrating disparate tribes who speak mutually unintelligible languages and dialects. Western civilization was founded on the universality of Latin first as an administrative language for the Roman Empire and later as the lingua franca of Christendom. Before the principle of national sovereignty was established at the Treaty of Westphalia in 1653, most Europeans were in a sense all dual citizens, that is, citizens of the political jurisdiction of their residence and, at least in theory, citizens of a Christian Empire founded on the ruins of the Roman Empire. The Church provided a degree of unity to the assimilated barbarian invaders of medieval Europe—a unity, to be sure, honored more in the breach than the observance. From the Thirty Years War to the Napoleonic Wars to the two World Wars of the 20th century, Europe collapsed into ethnic conflict from which it emerged weakened and enervated.

Chinese civilization integrated disparate peoples in an entirely different way: The system of characters that Leibniz so admired became the universalizing principle for integrating peoples who still speak 300 dialects belonging to six major language groups. Mandarin, the Beijing court dialect, is still spoken fluently by a minority of Chinese, but literacy in the ideogrammatic written language is universal. China has also had its lapses into regional and ethnic conflict, most recently during the warlord period of the 1920s and 1930s, and on occasions too numerous to mention in its long history. In addition to its common written language China has two features that integrate its enormous and diverse population: The meritocracy of the examination system, and national infrastructure. Unlike Europe, China is united by great river systems whose management has required an enormous centralized effort for at least 5,000 years.

China’s geography made a centralized state indispensable. America’s founding documents proceed from the rights of the individual as granted by “nature and nature’s God,” and view the state as a compact to which individuals assent freely for their mutual protection and benefit, limited by the right of each man to pursue his own mode of happiness, to speak his own mind, and live with a minimum of interference by public entities. In China, the state is a precondition for a good life among its citizens.

China, as Prof. Wen emphasizes, has distilled the experience of millennia of settlement; the Chinese were a settled farming folk for almost four thousand years when the ancestors of today’s Westerners—the Goths, Huns, Vikings, Slavs, and others who came to Europe after Rome collapsed—were still migrants. If China is the epitome of a settled culture, America is the exemplar of a restless one. Our culture is suffused with it, from our national novel Huckleberry Finn with its journey that can only begin again, or Frederick Jackson Turner’s essay on the frontier, or Stephen Vincent Benét’s 1943 epic poem “Western Star” with its opening motto, “Americans are always on the move.” Hollywood made migration to the West a metaphor of redemption, as in John Ford’s 1939 film “Stagecoach.” In the US journey it is not the destination but the journey that matters, and it is a journey that by its nature cannot reach its destination, because the Heavenly City is not to be found on earth.

The interiors of an old Byzantine church are shown in the Jabalia refugee camp in the northern Gaza Strip, on Jan 24. The book regards Western civilization as “migrant” and Chinese civilization as “Sedentary”. (Rizek Abdeljawad / Xinhua)

The interiors of an old Byzantine church are shown in the Jabalia refugee camp in the northern Gaza Strip, on Jan 24. The book regards Western civilization as “migrant” and Chinese civilization as “Sedentary”. (Rizek Abdeljawad / Xinhua)

Prof. Wen inveighs against the idea that the West represents a civilizational norm. He is entirely correct: the civilizational norm, if by “norm” we mean the most frequent outcome, is extinction. Linguists estimate that nearly 150,000 languages have been spoken on earth since the dawn of humankind; of these a few thousands still are spoken, a number that will be reduced to a few hundred in a century or so. But China defies even this normative definition; it is defined not by a spoken language, but by a written language that conveys meaning not by sound-meaning association but by visual representation.

Civilization must find ways to assimilate a myriad of tribes who speak different languages. America solved this problem in the past by assimilating immigrants into a common culture with a common language, such that Americans whose grandparents lived in Poland or Vietnam nonetheless share what Lincoln called “the mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone.” Whether it will continue to do so remains to be seen, now that the US project is under assault by theorists who claim that America was founded to promote African slavery and other forms of imperial oppression.

China grew from small civilizations in the Yellow River Valley to encompass the whole of the territory from the desert and the Himalayas in the West, the jungles to the south, the frozen wastes to the north, and the sea in the East. It assimilated peoples representing six major and three hundred minor language groups. As noted, three generations after the Communist Revolution, Mandarin remains a minority language.

In this respect China and America have more in common than any other two countries: They found a solution to the problem of integrating disparate ethnicities into a common polity, albeit by radically different means. But the solutions are so radically different as to produce two cultures that communicate with the greatest of difficulty.

Prof. Wen draws a bright line between "sedentary" Chinese civilization and "nomadic" Western civilization. “By analogy,” he writes, “one can sum up the difference in the lives of two individuals by thinking of one as a ‘wanderer’ and the other as a ‘dweller,’ meaning that the former has spent most of his life wandering, travelling or migrating around and the latter has never left his native land….The life of the ‘wanderer’ and the life of the ‘dweller’ are two very different lives. The life experience and perception, the character, temperament, demeanor and even the appearance of these two individuals will have significant differences. That is especially true if the wandering life of the first individual involves robbing and killing people and taking over the homes of others. If these two individuals meet, they inevitably will feel different in every way and regard each other as belonging to a different kind.”

China, argues Prof. Wen, is a “sedentary civilization,” whereas “Western, Orthodox Christian and Islamic civilizations are nomadic or migrant civilizations. Chinese civilization “was continuously settled over 5,000 years in a nearly circular geographical area centered on the Central Plains.” By contrast, “Western civilization as we know it today is a completely different entity. It is actually a third-generation civilization that was reborn on the ruins of the old civilization, and its birth, growth and expansion were always accompanied by large-scale migrations and invasions. The major historical events were, respectively, the invasion of the Roman Empire by the barbarians around the 5th century AD, the Crusades of the 11th to 13th centuries, and the great exploration and colonization of the New World after the 15th century. These three great migrations have constituted the main line of this civilization throughout its history, from its birth to the present day, and are characterized by Leopold Ranke as ‘three deep breaths.’”

“The same is true,” Prof. Wen adds, “for Orthodox Christian as well as Islamic civilization,” which “belong to the same new generation of civilizations that emerged from the ruins of ancient Greco-Roman civilization, the latter shifting geographically to the northwest and the former to the northeast. Since the rise of Islam in the 7th century A.D., and under the pressure of this new power, Orthodox Christianity has expanded northward to Eastern Europe, Russia and Siberia where many steppe nomadic peoples have wandered and conquered each other since ancient times. From the 16th to the 20th centuries, Russia expanded outward at an average rate of 130 square kilometers per day, or the equivalent of the territory of Estonia each year.”

And with this expansion “a large part of Russian society was in a permanent state of uninterrupted migratory wanderlust. Islamic civilization was also born out of an ethnic migration that began in the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century A.D., followed by a wave of migration to the east and north that was comparable in scale to the invasion of the Roman provinces by Germanic barbarians in the 5th century A.D.”

Prof. Wen continues, “Even Indian civilization is fundamentally different from Chinese. Because its society was divided and fragmented for a long time, subject to frequent foreign invasions, and lacking a longer period of unification, it did not have the characteristics of a sedentary civilization similar to China’s, despite its large sedentary civilization.”

He concludes: “Except for Chinese civilization, the other living great civilizations were not formed by a continuous, large-scale sedentary farming history. Instead, they all inherited the prehistoric lifestyle of hunting and gathering and retained its characteristics long after the genesis of civilization…. From the perspective of ancient China,” they “resembled the nomadic peoples who appeared from four directions surrounding Zhou dynasty. China viewed them from the perspective of sedentary societies that developed social complexity and a mature writing system, that is, as barbarians: wandering societies that lived without fixed habitation and migrated over long periods of time, whether they were horsemen, camel-riding or boat peoples. The ancient Chinese referred to such societies collectively as ‘Xingguo’ (Moving Kingdom), as distinct from the ‘Juguo’ (Settled Kingdoms) such as ‘Huaxia’ in China.”

“Sedentary” Chinese civilization and “migrant” Western civilization, Prof. Wen believes, differ fundamentally in their engagement with the world around them. Westerners should read The Logic of Civilization: The Interaction and Evolution of Chinese and Western Civilization, listen carefully to Prof. Wen and make the effort to see China through his eyes.

David Paul Goldman is Deputy Editor of Asia Times. His book You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World (Bombardier) appeared in 2020.