In this Aug 24, 2019 photo, pedestrians walk past shops in the center of Gothenburg, Sweden. (FREDRIK LERNERYD / BLOOMBERG)

In this Aug 24, 2019 photo, pedestrians walk past shops in the center of Gothenburg, Sweden. (FREDRIK LERNERYD / BLOOMBERG)

The woman overseeing one of Sweden’s biggest investment funds says ultra-low interest rates pose a bigger threat to her industry than the market sell-off caused by the coronavirus.

Ylva Wessen, the 49-year-old chief executive of insurer Folksam, has opted to sit out the panic caused by the spread of the virus without doing major portfolio adjustments. But with some of the world’s most powerful central banks resorting to emergency rate cuts, the real worry for long-term investors like Folksam is the prospect of very low rates for a very long time.

I think we’re all worried, as we don’t know where we’ll end up. These are troubled times.

Ylva Wessen, Chief Executive, Folksam

“This is top of mind everywhere in the life insurance industry right now,” Wessen said in an interview from her top-floor office in Stockholm. “I think we’re all worried, as we don’t know where we’ll end up. These are troubled times.”

READ MORE: Milan locks down, as nations scramble to contain virus

The Federal Reserve rocked markets on March 3 with a half-point rate cut designed to stem the damage caused by the coronavirus. Canada was quick to follow and there’s speculation more will come. The easing spells a new wave of extreme monetary policy that threatens to undermine the investing model of the pension industry and deplete the savings of future retirees.

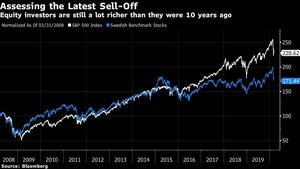

Low rates remain a “big strain” and the “number one challenge” for pension funds, Wessen said. And while stock markets did well last year, much of that dynamic was driven by the fact that capital “doesn’t have any other place to go,” she said.

It’s a logic that suggests equity valuations remain inflated. And Wessen says Folksam doesn’t really see any large-scale buying opportunities as a result of the sell-off triggered by fear of the coronavirus.

“Our strategy when this kind of event happens is to ride through it,” she said. “If you have the financial strength, that is what you do.” Wessen said Folksam, which manages about US$43 billion, has sold assets that are overbought. That’s given it “some leeway to buy the dips.” But the fund hasn’t gone bargain hunting, she said.

ALSO READ: Infections top 100,000 globally as Trump signs US$8.3b bill

In Wessen’s home market of Sweden, the big question now is whether the central bank will follow its peers and deliver a rate cut. The Riksbank raised its main rate to zero in December, ending five years of life below zero despite a slowdown in economic growth.

Policy makers have since argued that it makes little sense to tackle the coronavirus with rate cuts. But economists are increasingly predicting that Sweden’s central bank will have little choice but to follow its peers.

Wessen worries that another rate cut in Sweden would ultimately “hurt the market’s trust in the Riksbank.”

Meanwhile, Folksam is resorting to an investing strategy that much of the pension industry has turned to in response to ultra-low rates: so-called alternative investments. These tend to be long-term, often illiquid assets, such as infrastructure projects.

“These are very attractive investments,” Wessen said. But, “that means they get very expensive. We are all chasing the same assets.”