The SAR has a lot to catch up with its history and culture education. But, as the nation’s development continues at full speed, the community is more eager for a people-centered reading of shared trauma, building narratives rooted in the country’s own worldview. Luo Weiteng reports from Hong Kong.

A few months ago, a discussion on Chinese social media platform Xiaohongshu (RedNote) caught Guo Wangyue’s attention. The author of the thread was advocating for a study on war trauma in a Chinese context, and the response was overwhelming — commenters shared family scars tracing the chaos of World War II and earlier, realizing for the first time that their pain had a name.

For Guo, this wasn’t a new discovery, but was about seeing her long-held thoughts reflected in the public consciousness. Having studied psychology since her undergraduate years, the second-year doctorate student at Columbia University is increasingly convinced that Chinese psychology needs its own architects to build theories that belong to the people.

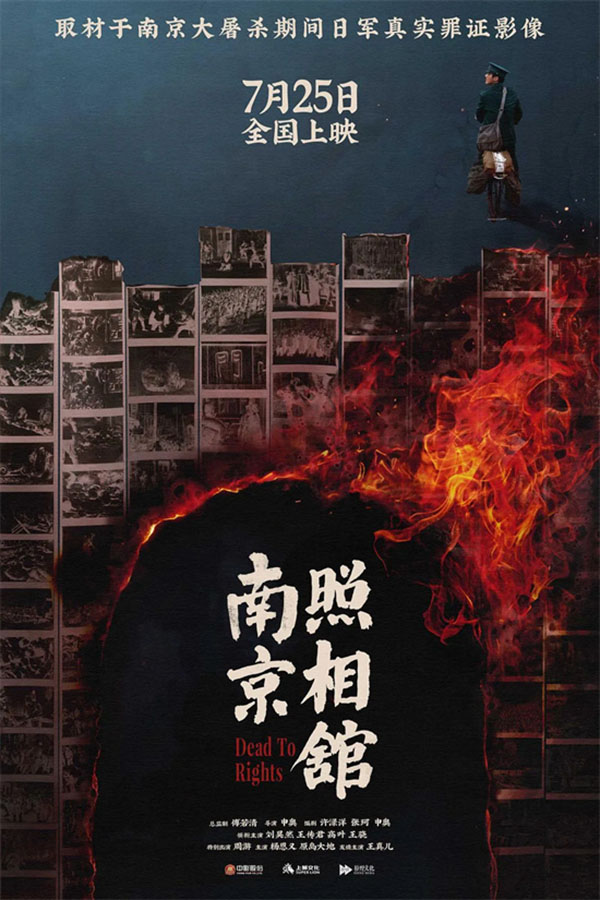

READ MORE: Film on Nanjing Massacre officially released in Hong Kong

“The West has The Lost Generation to explain its post-war psyche. We also see the term ‘intergenerational trauma’ applied to indigenous groups in Canada and Australia, the legacy of black slavery, and the holocaust survivors,” notes Guo. “Yet, when it comes to us, the pages are almost blank. Even freely editable sources like Wikipedia lack case studies from Asia.”

For years, the psychological devastation and cultural rupture of war have been major issues that people have avoided discussing. Rising from the ashes, post-war China has been racing against time, haunted by the fear that “backwardness invites aggression”. In a desperate hurry to rebuild, the nation rushed forward, with unhealed wounds beneath the surface.

“The timing is everything,” observes Legislative Council member Lau Chi-pang. “When survival is the priority, a country cannot afford the psychological burden of its deepest traumas. Discussion of this kind wasn’t possible before.”

Today, however, with national development reaching a tipping point, the public has gained collective confidence to revisit China’s most painful history as shared heritage. “Over the last two to three years, the way Chinese people look back at the darkest chapters of their past is worlds apart from 10 years ago. Such markedly stronger self-assurance and a fundamental shift in mindset are the key social and cultural phenomena to watch,” stresses Lau, who is also a professor in the Department of History and coordinator of the Hong Kong and South China Historical Research Program at Lingnan University.

The weight of history

For young people, the past remains hugely influential. The destructive toll wreaked by invaders echoes through generations. Children raised amid violence, humiliation and displacement inevitably carried these horrors inward, leaving a heritage of unspoken pain for their offspring.

Guo herself has long struggled with a fraught relationship with her mother, and is no stranger to the intensifying online debates around “East Asian family trauma” and relentless pressures of “involution” culture. She once sought answers everywhere — from professional psychology to the abstractions of astrology. The critical lens of post-war trauma gave her a way to read these tensions without reducing them to cultural flaws or national characters. This people-oriented perspective allows her to connect the dots of “intergenerational wounds” and the clarity and understanding necessary to meet her mother.

“When we talk to our elders, their refrain is always ‘we had nothing back then’,” Guo reflects. “What puzzles us and what we once dismissed as quirks — never wasting a grain of rice, the emotional walls they built against intimacy, their obsession with war dramas — were all born from scarcity and deprivation. Even their strict rules about drinking hot water and keeping us out of the rain suddenly make chilling sense when you remember the trauma of germ warfare that ravaged so many regions.”

That individual awakening counters a long-standing void in the narrative. For decades, market-driven war narratives tailored for international approval are either recycled fashionable anti-war tropes or spotlighted “moments of aggressors’ humanity”. Such storytelling was a quiet pressure on Chinese audiences to forgive and repay violence with virtue, all while ordinary people who bore the brunt of the suffering stayed out of focus.

This form of “political correctness” extends to academia. Yau Yat, executive director of the Hong Kong-based Academy of Chinese Studies, points to “a truly strange phenomenon” where some scholars in the special administrative region and on the Chinese mainland feel compelled to preface every speech or article with a disclaimer: They study the war not to incite hatred, but to advocate for peace.

“The irony is we rush to prove our moral innocence to the perpetrators who have never apologized, and still openly deny their crimes,” says Yau. “The uncomfortable truth is that, among the Japanese historians and education scholars I know, none believes Japan committed grave wrongdoings in World War II. Their only regret is picking a fight with the United States and losing. They don’t oppose war. They oppose losing it.”

Breaking the silence

As 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), the silver screen finally shows no disclaimers, refuting decades of carefully curated denials.

Dead to Rights (released as Nanjing Photo Studio), based on real events, smashed summer box office records with more than $3 billion yuan ($425 million). Set during the Nanjing massacre perpetrated by Japanese troops in late 1937, the film follows a group of Chinese citizens who sought refuge in a photography studio in Nanjing, the then national capital.

Forced to develop photographs taken throughout the city, they uncovered evidence of horrific war crimes and risked their lives smuggling the negatives out. For once, a Chinese film dares to say the unsayable. Its iconic line was uttered by a dying civilian to a Japanese military officer: “We are not friends. We never were.”

Director Shen Ao is equally blunt. He describes Japan’s wartime “goodwill photos” as “staged tools of propaganda” — soldiers smiling with children, while slaughter unfolded outside the frame. “This hypocrisy must be exposed.”

That old “goodwill” logic still shapes Japan’s global narrative today as its government casts itself as a victim of two atomic bombs, while dismissing both the film and China’s remembrance as “anti-Japan”. Globally, with historical revisionism on the rise, the 80th anniversary assumes a greater significance, making the public awakening more urgent than ever.

Lau senses change closer to home. As cochief editor of the Chronicle of the Hong Kong-Kowloon Brigade, he has seen the book revised for a sixth edition, selling more than 7,000 copies and entering local classrooms.

Before the handover, Hong Kong’s World War II narrative was centered almost exclusively on Britain’s 18-day defense. What remained untold were the years that followed — the British surrender, the occupation and the Hong Kong-Kowloon Brigade’s continued resistance until Japanese surrender on Aug 15, 1945. For nearly two weeks thereafter, the brigade administered parts of Hong Kong.

These episodes, almost erased from collective memory, are overdue for attention, Lau contends. He recalls meeting Hong Kong’s young people who were convinced that British rule had stretched unbroken from the mid-19th century until 1997.

Reconstructing local memory

The nation has its history and the city has its chronicles. Compiling local gazetteers is a uniquely Chinese cultural tradition that is vital to help Hong Kong reconnect with its roots. Lau and his team have spent nearly two decades reconstructing these overlooked chapters. A firm believer in a people-centered view of history, he sees the next frontier of research in the quiet force of ordinary people’s participation.

To Yau, recounting Hong Kong’s wartime story is a long game — one that demands persistence. The city may not lack textbooks, he notes, but its teachers no longer carry the memories that give lessons weight. Classrooms default to abstract appeals for peace, while the brutal realities of Japan’s three-year-and-eight-month occupation of Hong Kong remain obscured.

“In a city where affection for Japan runs deep, such truths can feel out of place,” Yau reckons. Still, he holds onto hope. “Ten years ago, telling the country’s story in the SAR was a struggle. Today, people are willing to listen.”

This year, Yau has witnessed more commemorations for the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression than ever before in Hong Kong. Yet, he worries about tomorrow. Once the 80th anniversary passes, will the momentum endure?

Above all, he returns to a foundational question: What exactly are we commemorating? “We remember the price of weakness, the sacrifices that defeated fascism and the resilience that shaped our national identity,” Yau asserts. “We remember how China forges its own path to modernization, breaking away from the ‘jungle logic’ of conquest and colonization the world had once accepted as destiny, and built instead on the labor, discipline and collective will of ordinary people. That clarity is still missing in many local commemorations.”

The journey of remembrance is far from abstract. The discovery of a live war bomb relic in Quarry Bay in September served as a stark metaphor. The explosive was still live — just as the impact of the war remains undissipated. The city sits atop layers of history and, like the bomb, these stories demand careful handling.

For psychology researcher Guo, this excavation is internal. She has started piecing together the fragmented narratives of her elders, realizing how “terrifyingly short” the distance is between “then” and “now”. China’s ascent from a war-torn, impoverished land to an economic powerhouse has created an illusion where many mistake speed for healing. But history has its own clock, and some wounds need generations to mend.

“Being seen is the beginning of healing,” Beijing-based scriptwriter Han Lu says. “To heal is to rebuild the very order of one’s world. Unraveling this knot could elevate the mental well-being of the entire population.”

Forging a new narrative

Beyond the languages of psychology, sociology and history, Han finds solace in the spiritual richness of traditional culture. These ancient roots offer a unique grounding to anchor the modern Chinese spirit and, perhaps, a healing philosophy for a world divided by inequality and unsettled by the collapse of old certainties.

Her insights land where Gu Hongming — a Malay-born Chinese man of letters during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) — once stood: “The serene and blessed mood which enables us to see the life of things: that is imaginative reason, that is the spirit of the Chinese people.”

As China rises, debates over “engineer-led development” and the supposed “uselessness” of humanities graduates grow louder. “Master math, physics and chemistry, and you can go everywhere” once captured the country’s survival logic in an era defined by material reconstruction and catch-up industrialization. Yet the humanities were squeezed externally by Western dominance of global discourse and, internally, by domestic scholars who look to the West for the sole validation.

Today’s competition is as much ideological as industrial. From Japan’s carefully curated victimhood to Western Normandy-centric framing of World War II that sidelines the Eastern Front and diminishes China’s sacrifices, historical revisionism and selective storytelling continue to influence diplomacy, public opinion and global legitimacy.

The distortion is blatant: This year, US then-defense secretary Pete Hegseth praised the “warrior ethos” of the Japanese forces at Iwo Jima, site of a major battle in World War II, on its 80th anniversary. Meanwhile, the US State Department marked the Hiroshima anniversary by celebrating the two nations standing together to end the war.

This is where the humanities matter. And Hong Kong, long positioned as an East-meets-West hub, should have a role to play — though reality remains far more complicated. This year’s surge in commemorative events has kept Lau continually on the move. “Hong Kong simply lacks people who know this history, and even fewer willing to devote years of quiet work to it,” he says.

Lau attributes the gap to the city’s “functional” identity — a melting pot where migrants come to earn a living, not to cultivate tradition. Even the multibillion-dollar West Kowloon Cultural District, grappling with a funding crisis, is regarded by many locals more as a space for leisure than for serious cultural engagement.

A devoted calligrapher, the lawmaker once questioned the city’s readiness to shoulder a cultural exchange mission in a Legislative Council meeting. “Hand most Hong Kong people a calligraphy brush and few would think of practicing one of the Four Arts of the traditional Chinese literati,” Lau joked. “For many, it’s just as easily a tool for basting barbecue.”

History and culture education have long been thin, leaving the city with much homework to catch up. Yet, Yau points to a structural constraint not unique to Hong Kong — its academic frameworks, accreditation systems and cherished rankings are all “second-hand Western imports”, making the SAR dance within a borrowed frame.

But, building the country’s narrative independence, for both post-war trauma and people-centered wartime memory, requires indigenous perspectives rather than inherited lenses. This quiet work of naming one’s own world is already visible in cultural production, Han notes. Last year, China’s first AAA video game, Black Myth: Wukong, won widespread international acclaim partly thanks to the globally recognized icon of Sun Wukong. Its sequel, Black Myth: Zhong Kui, however, features Zhong Kui, a figure central to China’s mythic order but virtually unknown abroad. “It marks a quiet but firm turn toward telling stories from within, not outward toward approval,” Han stresses.

ALSO READ: HK marks 80th anniversary of victory against fascism

To Yau, this task of “naming” is even more critical in theory building. He sees the SAR’s role in helping China craft its own theoretical language to explain its development path and institutional innovations. It remains a vocabulary the world has yet to truly grasp, and one the Global South is eager to learn.

“The contest of theories is the contest above all,” Yau notes. But, such battles are time consuming. Building a new discipline that speaks to the Global South, and breaks free from inherited Western paradigms, requires new thinking, collective will, institutional imagination and the resolve to start from scratch.

In a moment of global reordering, having one’s own voice matters.

Yau doesn’t expect global persuasion, but argues the need for persistence. “This is the kind of work where you do what is right and ask no reward for the road ahead. And, Hong Kong must be part of it.”

Contact the writer at sophialuo@chinadailyhk.com