Seals and wooden slips reveal an elaborate and efficient administrative system, Deng Zhangyu reports in Kunming.

In 1956, a golden seal with a snake-shaped decoration was unearthed from ancient tombs at the Shizhaishan site in Kunming, capital of Yunnan province.

Bearing the inscription "Seal of the King of the Dian Kingdom", the artifact stands as compelling evidence of the ancient Dian Kingdom's existence, a regional state that thrived more than 2,000 years ago on China's southwestern frontier.

The gold seal dating to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) was granted by Emperor Wu of Han to the King of Dian after the local regime pledged allegiance, according to Western Han Dynasty's historian Sima Qian's Shiji, or Records of the Grand Historian.

For years, the enigmatic southwestern frontier kingdom and its interactions with the central authority of the Western Han Dynasty have been shrouded in mystery, known only through brief mentions in Shiji. However, recent archaeological discoveries at Hebosuo site in Kunming's Jinning district have brought to light the most compelling and detailed physical evidence.

READ MORE: Unearthed objects reveal old Yunnan

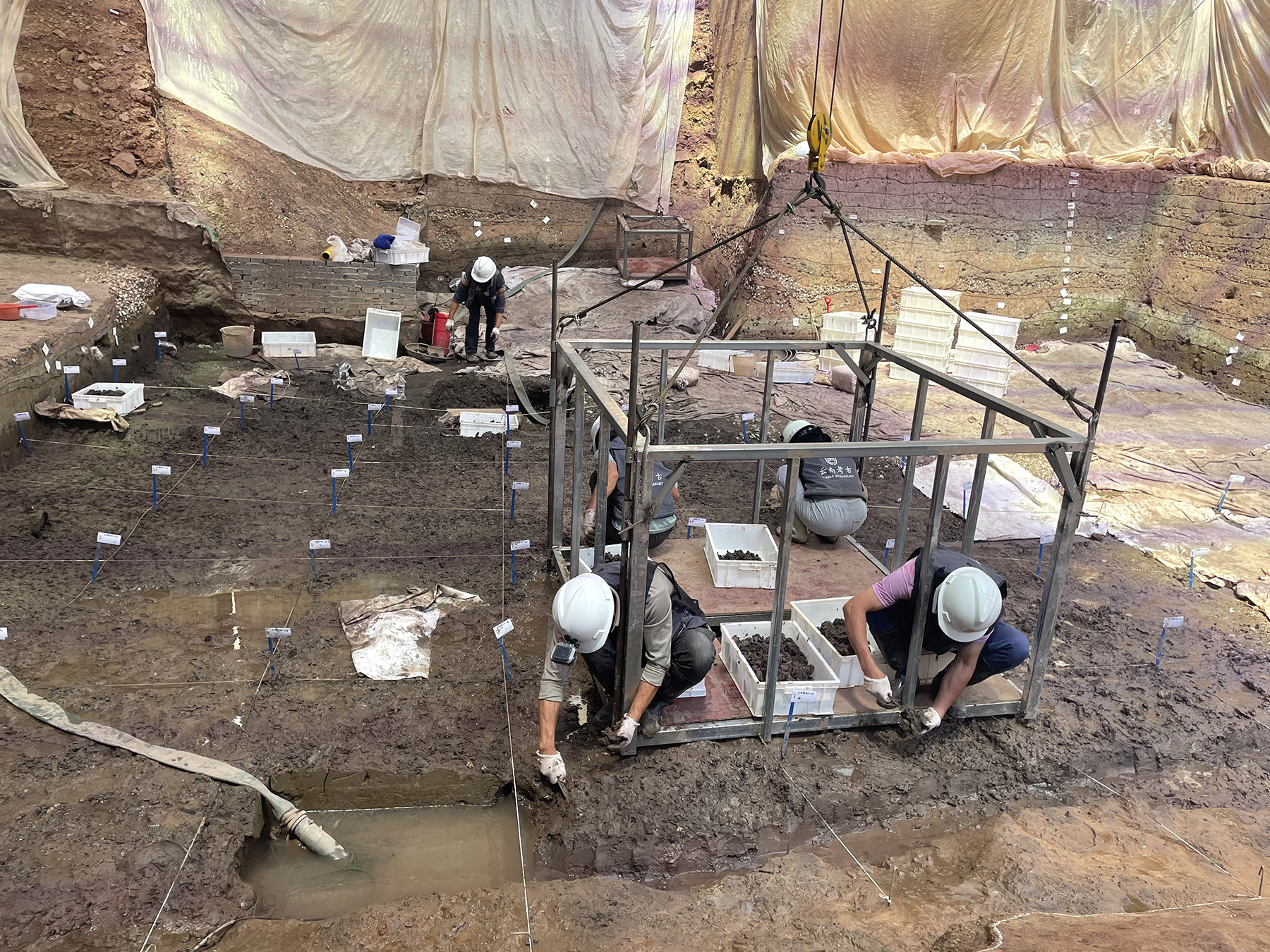

So far, over 2,000 clay seals have been unearthed at the Hebosuo site, revealing more than 10 different official titles. Additionally, more than 50,000 wooden slips have been discovered, which cover a wide range of topics, including official documents, legal papers, household records, postal communications, goods transactions and family property declarations.

There are two notable highlights among the clay seals used to secure documents, much like stamped wax on an envelope. These include the seal of the magistrate of the Yizhou Commandery and the seal of the Dian Kingdom, each bearing distinctive inscriptions.

These clay seals clearly indicate that the central government of the Western Han Dynasty had exercised its governance over the Dian Kingdom, says Jiang Zhilong, a researcher at the Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology.

From the gold seal of the King of Dian to the clay seal of Dian, Emperor Wu of Han's strategy for managing the southwestern princedom is very clear and clever, says Jiang, also a veteran archaeologist who has worked at the Hebosuo site for decades.

"On one hand, the emperor allowed the Dian Kingdom to keep its name and title for its king, along with certain privileges. On the other hand, he established an administrative system, including the position of a magistrate, to directly manage the region and keep the king in check," explains Jiang, adding that it also shows that after the Han Dynasty established the Yizhou Commandery, Yunnan province — where the Dian Kingdom was located more than 2,000 years ago — it began a new chapter of integrating into a unified, multi-ethnic China.

It's also the reason that the findings at the Hebosuo site were listed as one of the top 10 archaeological discoveries of 2024 by the National Cultural Heritage Administration in April.

Huo Wei, a professor from Sichuan University, said at the news release unveiling the top 10 list in Beijing that the archaeological discoveries at the Hebosuo site demonstrate that Emperor Wu of Han employed a very flexible and effective management approach in governing the southwestern frontier. This was also the earliest implementation of a "one country, two systems" method by the central authority in frontier governance.

"The rich discovery provides a detailed glimpse into how a frontier region of the Han Dynasty was governed, almost like an 'archive' from that time. We can see a very complete administrative system, from the grassroots level to the county, then to the commandery, and finally to the central authority, which complements the structure of grassroots officials during the Han Dynasty," says Huo.

The Hebosuo site is about 1 kilometer away from the Shizhaishan site, where ancient tombs of the King of Dian are located. In fact, after the ancient tombs of the King of Dian were discovered, Jiang and many other archaeologists spent decades searching for the residential and living areas of this remote small kingdom. However, they never connected the location of Yizhou Commandery mentioned in historical records with the capital of the Dian Kingdom. It wasn't until the unearthing of a large number of official seal impressions in 2018 that they realized the ancient capital of the Dian Kingdom was actually the later Yizhou Commandery.

The discovery of tens of thousands of inscribed wooden slips provides concrete evidence that this location was indeed the site of the ancient Yizhou Commandery. Previously, the existence of the commandery was known only from historical records. After 2021, a significant number of Han Dynasty city walls, moats, roads, and the foundations of large buildings have also been uncovered at the site, along with inscribed tiles and official seals related to the Yizhou Commandery.

The vast number of inscribed wooden slips and the task of organizing the inscriptions on them require considerable time and effort. Su Dongxiao has dedicated herself to sorting and studying these slips at the Hebosuo site for several years.

She explains that the inscriptions provide detailed records of the names of the 24 counties of Yizhou, along with a wealth of information reflecting various aspects of society at the time. This ranges from government administration, such as the taxation and judicial systems, to everyday matters like parcel delivery and household registration.

Among these wooden slips, there are more than a dozen featuring pictorial representations, a very rare type. Some of these depict local animals, such as horses used for transportation.

Su explains that this is likely because, after the Han dynasty central government took control of the area, there was extensive interaction with local society. The illustrations of horses on the slips might have been intended to showcase the unique characteristics of the local horse breeds.

Another pictorial wooden slip features a simple human figure. The facial area of the figure, including the forehead, eye sockets, and nose, was distinctly painted with red cinnabar. However, the specific interpretation of this image requires further research.

"These wooden slips are very detailed and reflect everyday life, vividly outlining various aspects of society and life in this county at the time. They are invaluable resources for studying a local regime during the Han Dynasty," says Su.

For Jiang, the archaeologist who has devoted to finding the Dian Kingdom since the 1990s, the discovery of the historical transition from the ancient Dian Kingdom to Yizhou Commandery was extremely challenging and took him nearly 30 years.

"It was like a blind person feeling an elephant. Archaeology involves piecing together these traces bit by bit to build an understanding of the entire past society," says the 59-year-old.

Before the archaeological discoveries at Hebosuo site, many thought that Yunnan was incorporated into the central authority during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) based on limited historical records. Prior to that, local regimes were in constant contention with the central government, says Jiang.

Their findings now clearly prove that as early as 109 BC, Emperor Wu of Han sent a general south to Yunnan, establishing the Yizhou Commandery and 24 subordinate counties. Consequently, the Dian princedom was officially incorporated into Han territory.

ALSO READ: Tracing the origins of Confucian inspiration

Jiang explains that Emperor Wu of Han set up the Yizhou Commandery to open up a new military route to strike at the rear of the nomadic Xiongnu people.

In order to effectively resist the threat posed by the Xiongnu from the western regions, he planned to send troops to the ancient Dian Kingdom, thereby encircling the Xiongnu from the southwest. This strategy aimed to weaken the threat to the Han Dynasty's borders.

"While strengthening central authority, the establishment of the Yizhou Commandery also promoted the stability and development of border regions, serving as a vivid illustration of the unity, inclusiveness, and peaceful nature of Chinese civilization," says Jiang.

Li Yingqing contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at dengzhangyu@chinadaily.com.cn