A five-year quest to re-create the Qingming Festival scroll has put the ancient craft back in spotlight, Zhang Yu reports in Shijiazhuang.

In a quiet workshop in Dingzhou, an ancient city in North China's Hebei province, a revolution was taking place, one silk thread at a time.

Under the steady glow of lamplight, the hands of master weaver Wang Pengwei guided a tiny shuttle through a forest of 20,000 vertical warp threads.

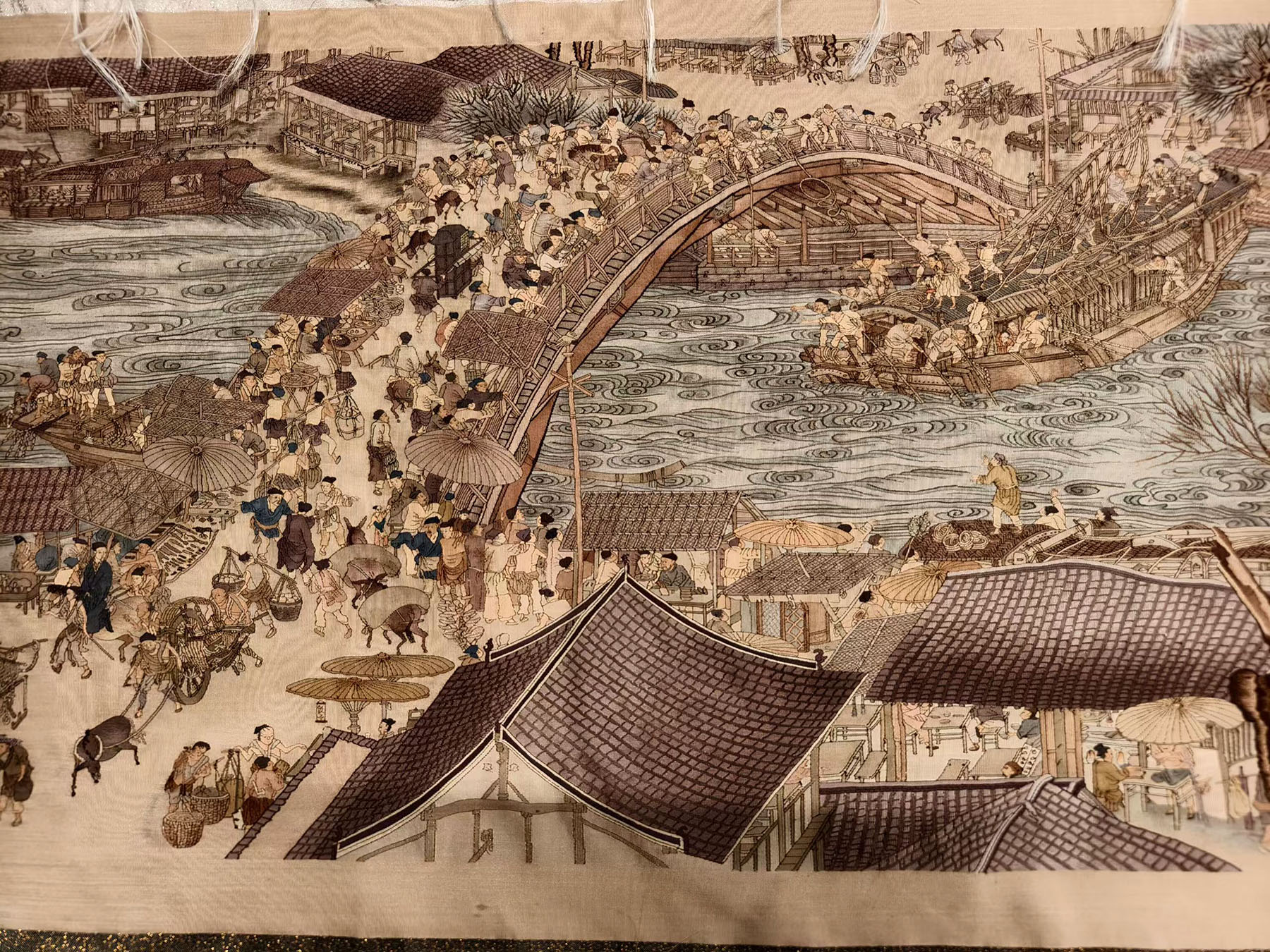

Each pass was a calculated move in a five-year-long battle to achieve the impossible — translating the ink-and-brush strokes of China's celebrated 12th-century scroll painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, into the shimmering, tactile language of silk tapestry weaving, known as kesi.

READ MORE: A rare sight to behold

This monumental endeavor, an 8.2-meter-long kesi replica of the painting, has recently attracted great attention and reignited interest in the ancient art form.

After its debut on China Central Television's program China in Intangible Cultural Heritage in October, it garnered a staggering 300 million views online, pulling the 2,000-year-old craft of kesi from the quiet halls of museums into the vibrant, trending spotlight of social media.

For Wang, the 57-year-old seventh-generation heir of the Dingzhou Wang family's kesi tradition, this was more than just a project. It was the fulfillment of a promise.

"The idea of creating a 'masterpiece for the ages' came from a deep respect for kesi," Wang says, her voice filled with quiet conviction.

"I've seen many artisans dedicate their lives to this craft. I always wondered, could I leave behind one piece that truly represents the pinnacle of this art? That would mean my life was not lived in vain, and I would not have squandered the skill passed down by our ancestors."

The choice of the Qingming scroll was deliberate.

Its sprawling panorama of more than 800 characters, numerous buildings, and bustling life details presented a peak no kesi artisan had ever dared to climb.

"Its unprecedented difficulty is precisely what made us determined to do it," Wang says. "If we were to do it, we would create the most exquisite piece."

The challenges were monumental. The original 5.28-meter-long painting had to be enlarged by 50 percent to allow the kesi technique to capture its most minute details.

A custom loom, 10 meters long, was built from scratch. However, the most profound challenge was human. Over 10 weavers had to work in perfect harmony.

"Each master's technique — the tightness of their weave, the density of the weft threads — was slightly different," Wang explains.

To achieve uniformity, the team underwent a grueling three-month training process, repeating the same weave daily until their collective output varied by no more than a single thread per centimeter.

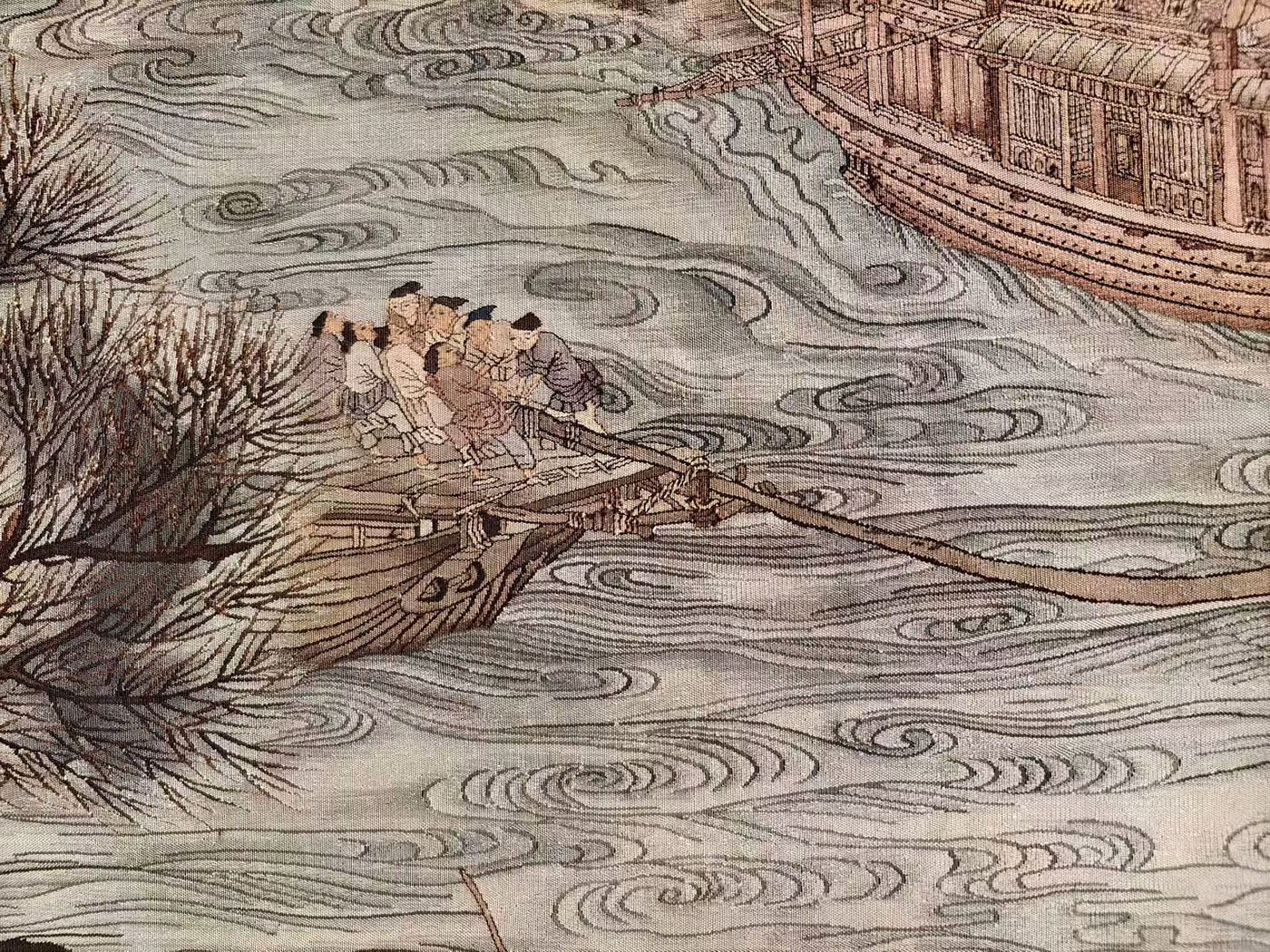

The soul of kesi lies in its defining technique: passing the warp and breaking the weft.

Unlike embroidery or regular weaving, kesi involves building up color areas with individual weft threads that are only woven where a specific color is needed.

This creates a distinct, carved effect, giving the craft its name, which literally means "carved silk".

Wang describes the process as "sculpting" with thread.

To create the robe of a single boatman, a shuttle — the tool used to carry the horizontal threads through the vertical threads on the loom — carrying dark silk would first outline the shape. Then, a shuttle with lighter-colored thread would fill in the body of the robe.

Where the shadow of a fold fell, a slightly darker thread would be introduced, using a technique called "long and short color graduation" to blend the hues seamlessly.

Each thread had to be pressed firmly into place with a bamboo tool, ensuring no color bled into its neighbor.

"For a few simple brushstrokes in the original painting, we might need a dozen shades of silk thread on a single warp line," Wang says.

"Our artisans had to stare at the warp, their eyes almost glued to the loom, pressing the weft with their left hand and quickly switching shuttles with their right. A day's work might yield only a few millimeters of progress."

The project consumed 126,000 work hours over five years.

There were moments of near-defeat. "There were countless times we wanted to give up. Our eyes were almost going blind," Wang recalls.

But the moment the finished piece was finally cut from the loom was unforgettable.

"My heart was pounding. I was so nervous, terrified the final product would be a failure. When it was successfully taken off the loom, everyone cheered and leapt for joy. That sense of achievement is something I will remember for the rest of my life."

The completion of the kesi scroll represents a triple triumph for Wang — it is a promise kept, a testament to the vitality of Dingzhou kesi, and a new path for intangible cultural heritage.

"It proves this craft has not been lost. Instead, it has gained new life in our hands," she says. "By creating a landmark work, we can let more people know about kesi and fall in love with it."

The widespread popularity has brought a wave of recognition and new responsibility.

"I was so excited that I couldn't sleep, not because of the fame, but because our years of persistence were finally seen," Wang says of the online reaction. "This attention proves that intangible cultural heritage is not an outdated craft, but a cultural treasure that can move people today."

The story of Dingzhou kesi, however, is not just about preserving the past, but also about innovating for the future.

This forward-looking mission has been passionately taken up by Wang Bo, Wang Pengwei's 35-year-old son and the eighth-generation successor.

Wang Bo's decision to embrace the family craft was not straightforward.

As a young man, he initially found the ancient tradition "too heavy" and instead spent over a decade building his own business in the agricultural sector.

For him, the change came during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I returned to Dingzhou and spent time with my mother," he recalls. "I saw the light in her eyes as she sat before the loom.

"I realized the old masters of kesi were becoming fewer, and young people were reluctant to learn. The craft was on the verge of being lost."

He then made the life-altering decision to leave his company and return home.

"Choosing kesi is like entering through a narrow gate to walk a long road, searching for a faint beam of light," Wang Bo says.

"This craft isn't profitable, and it's time-consuming. But its meaning is hidden in the details. The feeling of weaving a millennium of splendor with your own hands is something no business venture can provide."

Now, as a promoter of the craft, Wang Bo is injecting contemporary relevance into kesi.

On the program China in Intangible Cultural Heritage, he showcased Dream Weaving Space, an immersive installation where kesi has broken free from flat textiles to merge with light and shadow.

He presented innovative products like a brooch inspired by a plum blossom from a Palace Museum painting; and a tea mat, woven with nanotech-treated silk, that astonishingly repels water, oil and stains.

"For young people today, the appeal of kesi isn't that it's easy to pick up. It's healing," Wang Bo says. "When you're weaving, your mind empties. You only think about how to successfully weave the next thread. This focus is more therapeutic than any stress-relief method. It allows you to slow down and see the beauty in details."

His vision for the future is clear: First, to master the core techniques solidly, ensuring they are not lost in his generation; then, to develop products that are integrated into daily life, so that kesi is seen and used in the home and not simply the preserve of museums.

ALSO READ: Forbidden gates swing open

The story of the kesi Qingming scroll is more than an artistic achievement. It is a story of a city, Dingzhou, reaffirming its identity as the cradle of this sublime art.

"In cultivating a new generation of artisans, we have partnered with Jizhong Vocational College to establish a three-year college-level diploma program in kesi, pioneering a mentorship inheritance system within higher education," Wang Pengwei says, adding that the program now enrolls at full capacity every year.

In the hands of Dingzhou's weavers, 2,000 years of artistry is not only preserved, but is beginning its next chapter.

Contact the writer at zhangyu1@chinadaily.com.cn