China-Uzbekistan joint excavations at ancient burial site point to the influences present in the Fergana Valley, Wang Ru reports.

Even today, silk is something of a luxury, so it is not difficult to imagine the awe it must have inspired when it was introduced from China to Europe. The fabric is as soft as a breeze and lustrous as a pearl, and this marvelous material was not created for keeping warm, but for adding glamour to life.

Maybe it's because silk was so impressive that the road it once traveled on was eventually named after it in the late 19th Century, when it became known as the Silk Road. However, because it is an organic material that decays with time, few traces of silk have ever been found at the ancient sites along the historical routes.

READ MORE: Sands of time reveal secrets

Silk, and other evidence of contact, has been found as a result of excavations carried out since last September by Chinese and Uzbekistani archaeologists at the Munchaktepa site in Uzbekistan's Fergana Valley, proving it was an important artery along the Silk Road that played a significant role in cultural communications between China, West Asia, and Europe, according to Liu Tao, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and leader of the Chinese team at Munchaktepa.

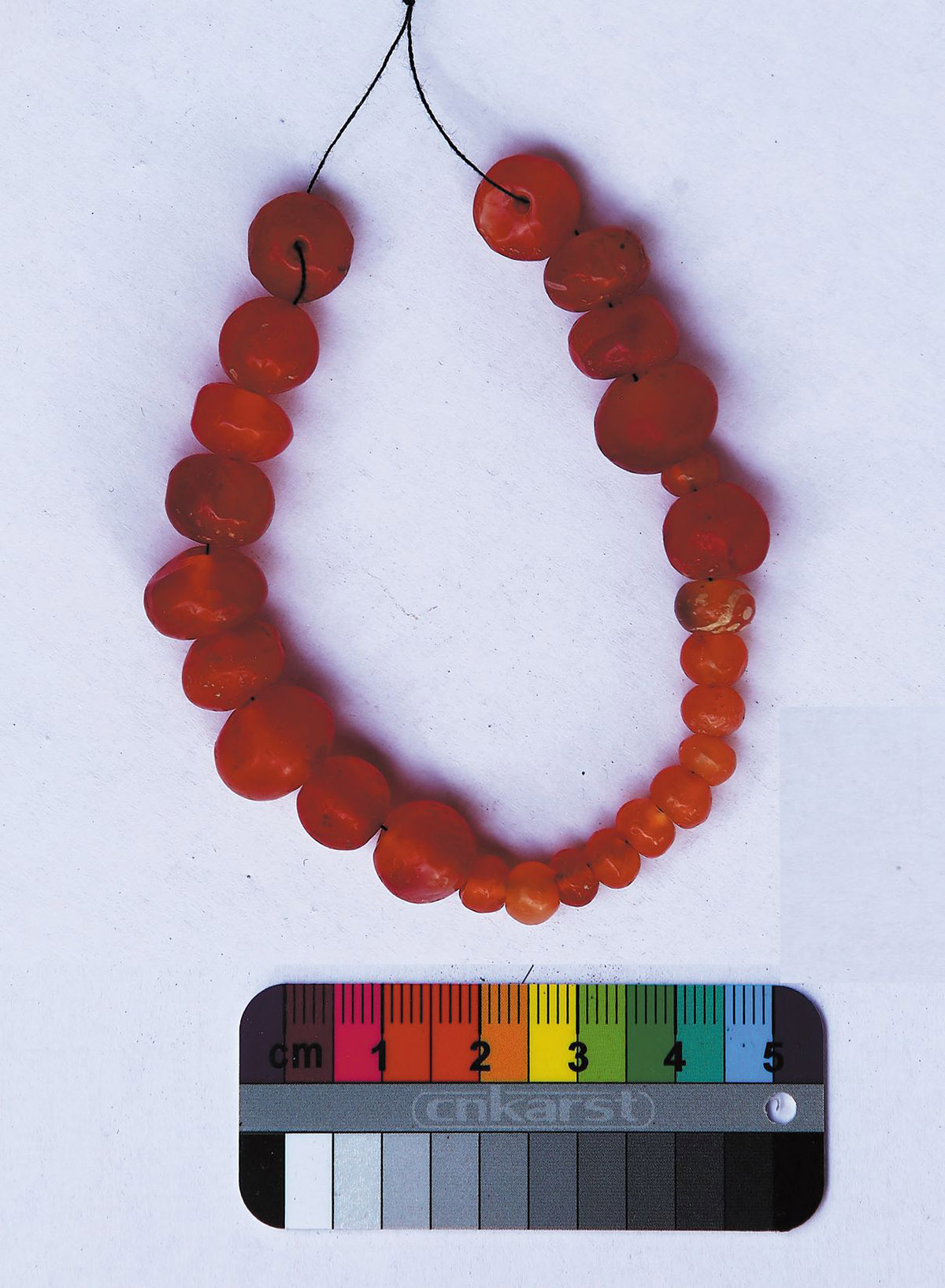

The site is located on a plateau east of the town of Bekabad on the banks of the Syr Darya River. It was accidentally discovered and excavated for the first time in the 1980s, when many strings of beads were unearthed in its tombs. As a result, the site was named Munchaktepa, which means "the plateau of strings of beads" in Uzbekistan.

Through research, Munchaktepa has been identified as a burial site belonging to the people who lived in the neighboring site of Balandtepa, where the remains of a city dating to the same period as Munchaktepa have been found some 30 meters away.

According to Ali Aisa, a member of the Chinese archaeological team, Munchaktepa is roughly contemporaneous with the period in China spanning the Three Kingdoms (220-280) to the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-581).At the time, the Silk Road was the site of much trade and frequent cultural exchange.

As they sought to clarify the size of the burial area, as well as the spread and structure of the tombs, and detailed information about funerary objects, archaeologists found six new tombs — five small ones containing only one or two bodies with few funerary objects, and one larger one containing the remains of at least 24 individuals. Those in the small tombs seem not to have been buried in coffins, while those in the large tomb were buried in coffins made of reeds.

"As the site is by a river home to many aquatic plants, it's logical that people would have used reeds to make coffins, and that can be seen as characteristic of local funerary customs," Liu says.

They also found the large, well-preserved foundation of a house to the south of the tombs, referred to by archaeologists as F1. When viewed from above, it is nearly square in shape, with each side measuring approximately eight meters in length.

Based on the features of the foundation, such as the house having only an entrance in the east, a domestic hearth facing the entrance, traces of burning on the ground and east wall, and overturned pottery vessels outside, archaeologists believe F1 may have a connection to Zoroastrianism.

Zoroastrianism was an influential Persian religion that originated in the 6th century BC. Before the arrival of Islam in the 8th century AD, it dominated a large area of West and Central Asia.

According to preliminary carbon dating, the larger tombs and the F1 structure date back to about 400, while the small tombs are from 750.As Munchaktepa is closely linked with nearby Balandtepa, Liu says the team will study Balandtepa to determine whether Munchaktepa was used continuously from 400 to 750 by the same group of people, or if it was used by one group in 400 that later migrated, and then by another group in 750.

The funerary objects discovered include pottery vessels, coins, bronze mirrors, silk, and many strings of beads. Liu says the coins discovered this time are circular with a square hole, typical of ancient Chinese coins, which were also made in neighboring countries under Chinese influence.

They found one coin with traces of rope on one of the corpses' chests, suggesting that it was a pendant worn around the neck. As this was the first time archaeologists had found Chinese coins being used as jewelry in Central Asia, they were pleasantly surprised.

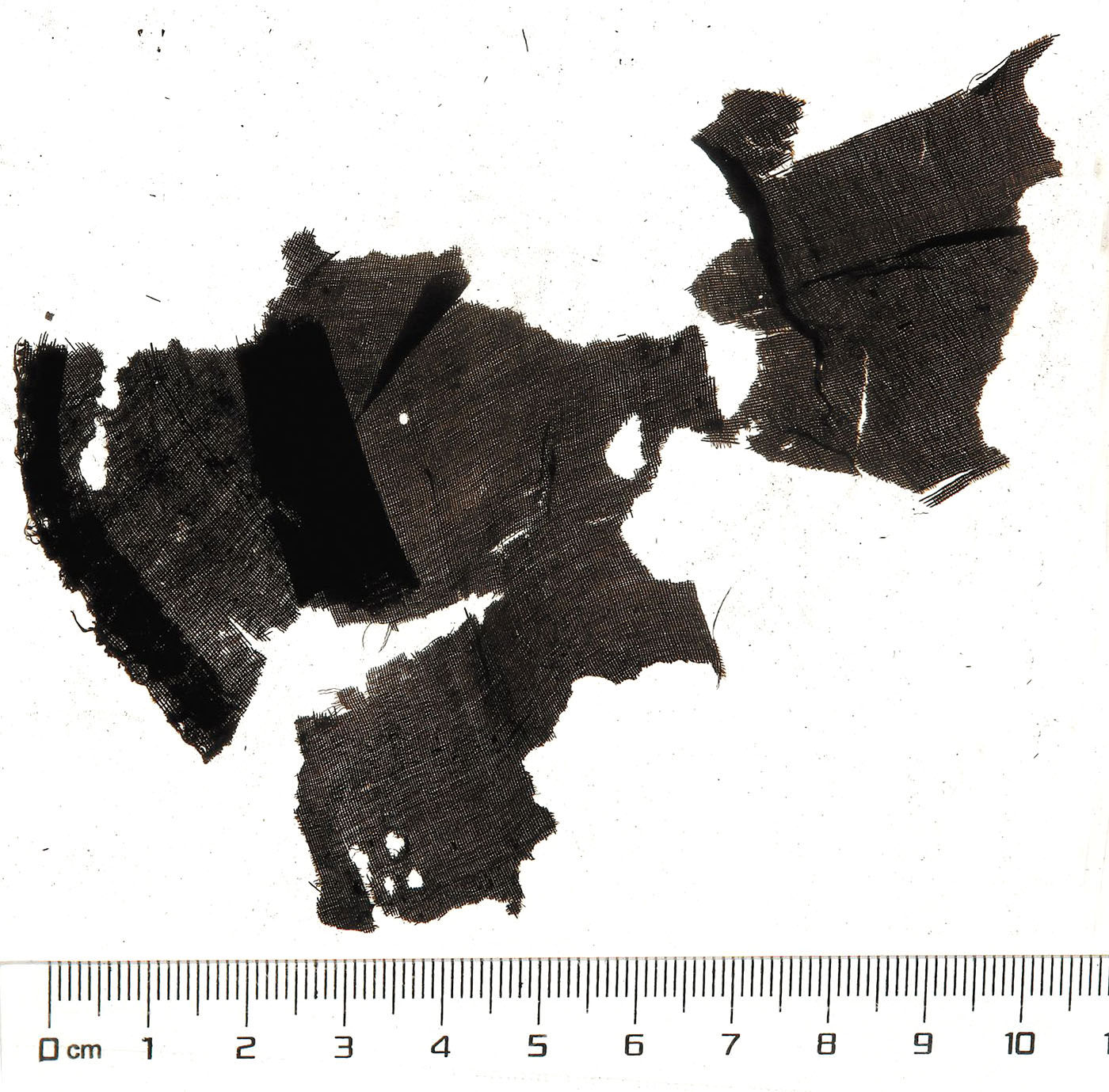

Archaeologists have found more than 20 fragments of silk with visible patterns. They were found stuck to human bones, and appear to be the remains of clothing. This is the second time archaeologists have found silk at the site. In 1987, Uzbekistani archaeologists also found silk, which Chinese and Uzbekistani scholars later studied, concluding it was probably produced in China.

"This time, we want to apply the most advanced measures to see if we can gain a more concrete understanding of the origin, period, and type of silk," says Liu.

Bronze mirrors without handles and with a raised mirror knob in the center of the circular plate have also been found from the site. They are often considered typically Chinese in style and are very similar to ancient Chinese mirrors, he adds.

The findings prove that different cultures met and mixed in the Fergana Valley. "Burial practices with local characteristics, artifacts with Chinese cultural elements, and the house foundation with Zoroastrian features from West Asia illustrate this cultural integration," says Liu.

Historically, the Fergana Valley was in close contact with China. Chinese records yielded clues as to the location of Dayuan, an important Hellenistic ancient state along the Silk Road that existed during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220).

"Chinese archaeologists have a natural advantage in studying this area because we have records. By combining them with archaeological findings, we can develop a better understanding of the valley," says Liu.

Based on Munchaktepa's location and date, as well as Chinese records, archaeologists believe the inhabitants of the tombs might be related to the Hephthalitai, nomads who migrated to Central Asia at the end of the fourth century, but further research is required to confirm this hypothesis.

According to Aisa, the team closely cooperated with Uzbekistani scholars. "They did a lot for us, and even offered us more than what we needed," he says.

One example is that the Chinese team needed a space at their partner institute, the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, to organize and study the artifacts unearthed. When they arrived in Tashkent, local scholars had arranged a large office and bought desks, chairs and shelves, which the team had been prepared to buy for themselves. Consequently, they were touched by their colleagues' consideration.

Aisa says that Uzbek researchers use textbooks translated from Russian, which are themselves translations of Chinese texts from the 3rd century BC to the 10th century, a period spanning the Han Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty (618-907), to study that period of time. Unfortunately, the process of multiple translations introduced some misunderstandings of the original Chinese texts, which Aisa says he and his colleagues were able to help correct.

"They had access to Sogdian and Arabic literature from the 4th to 8th centuries, but before that, Chinese documents played a major role in recording local events. Our participation helped correct many misunderstandings in the translations of the Chinese records," he says.

This time, the scholars introduced a new method of box extraction to Uzbekistan. This is the process in which a custom-sized box is placed around an artifact to extract it along with the surrounding soil intact for careful cleaning in a laboratory.

"We believe laboratories provide a better environment and the conditions necessary for the careful cleaning and excavation of important artifacts. In laboratories, we can better protect artifacts from potential damage during the recovery process, thereby extracting more valuable information from these historical items," says Liu.

The Uzbekistani scholars had initial doubts about the technique, but after seeing its effectiveness, they embraced it.

ALSO READ: Breakthrough findings span from Paleolithic period to Qing Dynasty

"If using a Luoyang Shovel (a curved spade) to identify soil structure is a traditional technique of Chinese archaeologists, then box extraction and cleaning indoors is an important technique of modern Chinese archaeology. Uzbekistani archaeologists have an edge in their knowledge of materials. Our edge lies in our work methods and techniques. We worked together, discussed things, and gave full play to each other's strengths. In this way, we were able to work better together," says Liu.

Anarbaev Abdulxamidjon, an academic at the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan, told Xinhua News Agency that the concepts, methods, and techniques demonstrated by Chinese scholars in preventive protection, box extraction, and indoor cleaning have not only contributed to field excavations in Uzbekistan, especially when it comes to enhancing the level of on-site cultural heritage preservation, but have also illustrated the new achievements of China's archaeological techniques to the world.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn