Through the hands of artists and craftsmen, the world-famous caves become a mirror to the splendor of a glorious age in ancient China, Zhao Xu reports.

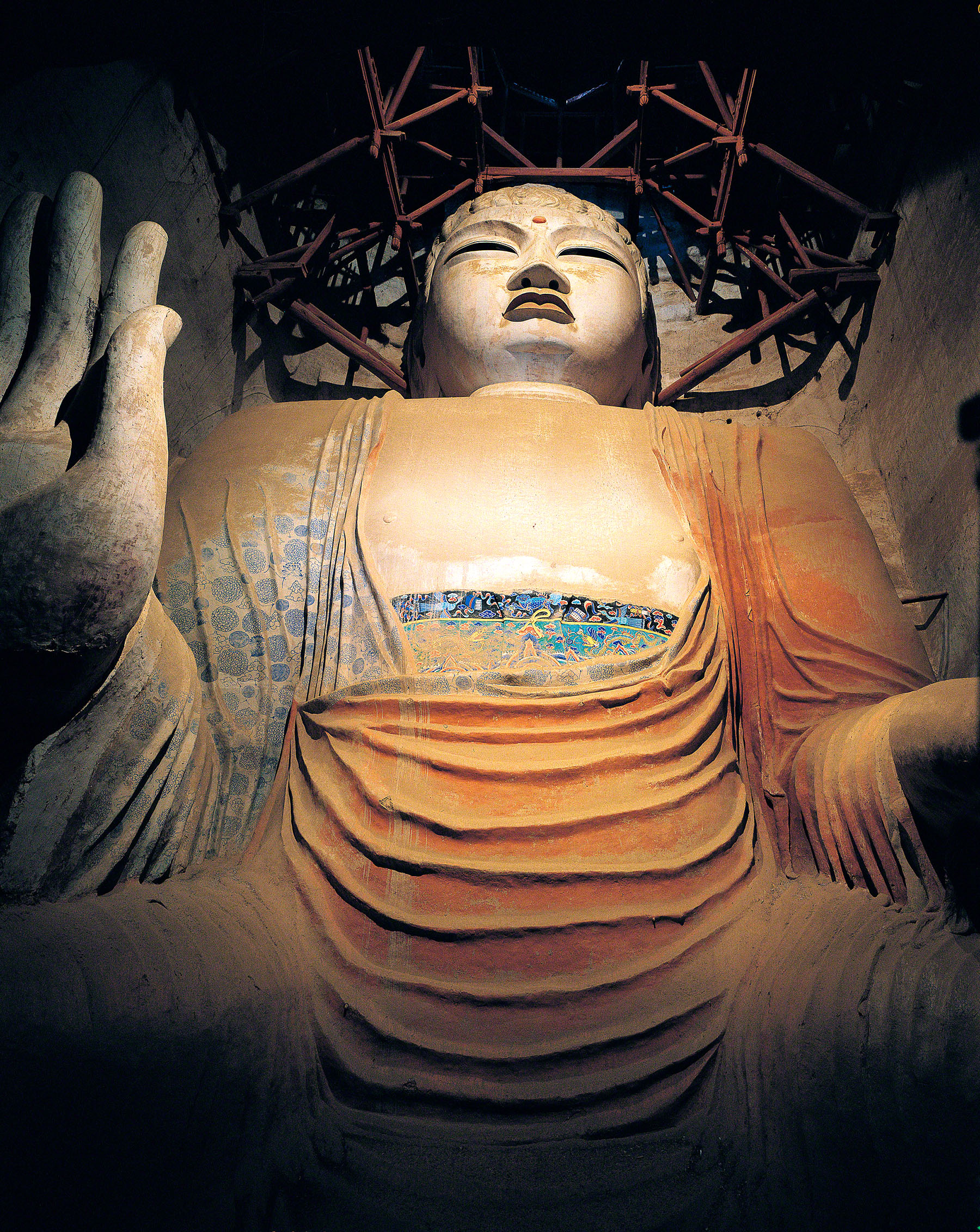

Almost anyone who visits the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province, finds themselves — quite literally — standing at the feet of a colossal 35.5-meter-high Buddha, carved from the region's iconic sandstone. Looking upward, visitors follow the gentle drape of his robe — its lower edge adorned with intricate dragon patterns, past the platform of his protruding knees where his lower arms rest, and up to his broad chest, softly folded chin, and tranquil visage. This awe-inspiring statue, which took 12 years to complete, stands as a silent testament to the power and ambition of one remarkable woman: Wu Zetian (624-705), the only female monarch to rule China.

In 690, after seven years of wielding power behind the scenes, Wu boldly seized the throne for herself, deposing her own son. To cement her legitimacy, her supporters portrayed her as the living embodiment of Maitreya Buddha, believed to be the future Buddha of the world in all Buddhist traditions. Temples were erected, and grottoes carved in his honor, serving as powerful symbols of visual propaganda. Against this backdrop, the construction of the monumental Buddha began in 695.

READ MORE: Lost relics from Mogao Grottoes to be 'digitally restored'

According to the local tourism bureau, with its towering height, the statue is today the tallest in Dunhuang and the third-tallest of all stucco sitting Buddhas in China.

Many believe that Wu Zetian was as much a product of her own ambition and political acumen as she was of her time. She rose to power during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), a golden era in Chinese history noted for its cultural brilliance, military strength, and exceptional openness. The Tang empire's military prowess ensured the stability and security of the vast ancient Silk Road network, allowing trade and travel to flourish.

Dunhuang, a vital oasis along this route, thrived as a cosmopolitan hub where merchants, pilgrims, and envoys converged.

"It's no surprise that, although grotto carving in Dunhuang began in the mid-fourth century, it wasn't until the Tang Dynasty that large-scale, fervent construction truly took off," says Zhong Na, a senior on-site tour guide, referring to the fact that out of the 735 existing Buddhist caves in Dunhuang, 236 have been dated to the time of Tang. "Many of these caves were commissioned by individuals involved in Silk Road trade. For them, carving a grotto was an act of devotion — an offering to the Buddha in hopes of securing divine protection on the unpredictable and often perilous journeys they faced."

This collective endeavor — carried out by legions of artists and craftsmen, many likely trained in workshops in the Tang capital of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an in Shaanxi province) — transformed Dunhuang's caves into a vivid, enduring photo book of the Tang Dynasty, preserving its splendor long after the glow of its prestige dimmed.

"We have every reason to believe that as the muralists brushed visions of paradise onto the plastered sandstone walls of Dunhuang, they were not only reaching for the celestial, but recalling the earthly splendor of Chang'an," says Zhong. "There, magnificent Buddhist temples rose amid the heady scent of incense — burned by the devout and brought there by Sogdian merchants, along with glittering jewels, exotic spices, and their spirited dances."

These wooden-structured temples found their way into the murals of Dunhuang, along with imperial canopies once used to shield emperors from the sun, ornate incense burners, and tree-shaped lampstands aglow with flickering candles. Such details, depicted on the walls of Cave 172 (all existing Dunhuang caves are numbered), have led some to speculate that the scene portrays Chang'an on the 15th day of the Chinese New Year, bathed in festival lights as it celebrated the Lantern Festival.

Throughout history, religious worship has rarely existed in pure silence, and Dunhuang was no exception. At this cultural crossroads, traditional Chinese instruments blended with those introduced via the ancient Silk Road, played by celestial beings floating above realms of Buddhist bliss. Their music must have followed the rhythm of twirling dancers who, as part of the scene, spin gracefully on ornate round carpets — much like Sogdian performers at lavish banquets in Chang'an.

"The frescoes' historical value can never be overestimated given the fact that few Tang Dynasty paintings, and ever fewer pieces of architecture, have survived to this date," says Zhong.

Her point was amply illustrated by Liang Sicheng (1901-72), considered by many "the father of modern Chinese architecture", and his equally talented wife Lin Huiyin (1904-55), a writer, poet and arguably the first female architect in modern China.

While poring over The Illustrated Catalogue of the Dunhuang Caves in 1937 — compiled by French Sinologist Paul Pelliot, who had visited Dunhuang in 1908 — Liang was captivated by a fresco titled Wutai Mountain Map.

Measuring 13 meters long and 3.6 meters wide, it was painted around the mid-10th century, roughly four decades after the fall of Tang Dynasty, to present a sweeping view of Wutai Mountain, a major pilgrimage site in Chinese Buddhism.

Whoever had created the bird's eye view had clearly marked and named 196 locations on the mural — including a certain Foguang Temple, which appeared to match one he had come across in archival materials shortly afterwards. Foguang literally translates to "the light of Buddha".

The couple wasted no time in journeying to Wutai Mountain, where, with the help of local monks, they succeeded in locating the main hall of the actual Foguang Temple. There, an ink inscription on a beam confirmed its dating to the Tang Dynasty.

"Until then, it was widely believed that no Tang Dynasty wooden structures had survived in China. The couple's discovery overturned that assumption — and they wouldn't have made it without that mural, painted on the western wall of Cave 61 in Dunhuang," Zhong says.

True to its name, Wutai Mountain Map illustrates two pilgrimage routes leading to the sacred mountain — one stretching from present-day Taiyuan in Shanxi province, and the other from present-day Zhengding county, Hebei province — covering approximately 160 and 260 kilometers, respectively. The map vividly portrays everything and everyone along these routes, from peasants trudging home with bundles of firewood, to lay believers erecting thatched tents in quiet valleys for moments of temporary meditation, and foreign envoys, their camels and horses laden with tributes, making their way toward a mountain temple.

The topography, rendered primarily in green and light brown, evokes the aesthetic of qinglyu shanshui — the "blue-and-green landscape" style of Chinese painting that emerged in the 5th century and flourished during the Tang Dynasty.

"The colors all come from natural pigments — turquoise for green, lapis lazuli for blue, cinnabar for red, kaolin (also known as Chinese clay) for white, and real gold for the gleaming gilt," says Zhong.

One figure who has received more than a few touches of gold is the Bodhisattva depicted in Cave 57 of the grottoes. Lavishly accessorized with gold bracelets and necklaces, as well as a gilded headdress the rich luster of which dances against the luminosity of her faint vermilion-colored skin, the Bodhisattva embodies the ideal of female beauty during the Tang Dynasty.

According to Zhong, as Buddhism made its way from India to China, the princely male image of the Bodhisattva gradually transformed into a more graceful and nurturing feminine form. Guanyin — the Chinese name for the Bodhisattva — literally means "One Who Hears the Cries of the World", a title befitting her divine role as the Goddess of Compassion. This transformation became especially pronounced during the Tang Dynasty, a time when women, as often seen in open and cosmopolitan societies, began to attain greater social standing.

The trend was exemplified by the political ascent of Wu Zetian, who rose to heights unobtainable if not unimaginable for women both before and after her. Like any shrewd power player, Wu understood the importance of offering hope to her subjects. It was no coincidence, then, that she aligned herself with Maitreya — the future Buddha — who, according to Buddhist belief, will descend upon the world 5.67 billion years after the nirvana of Shakyamuni, the historical founder of Buddhism, to bring abundance and peace to all.

Today, on the side walls of Cave 96, where the Giant Buddha sits, small holes remain clearly visible — believed to have been drilled to support the scaffolding essential for the statue's construction. These holes were first identified by renowned Chinese archaeologist and Dunhuang scholar Peng Jinzhang (1937-2017). His wife, Fan Jinshi — now 87 — is also a distinguished Dunhuang expert and former director of the Dunhuang Academy, China's premier institute dedicated to the preservation and study of this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

"Contrary to popular belief, Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin had never set foot here, yet they were able to make that discovery solely by studying the fresco — a fact that speaks volumes about the map's remarkable accuracy. Thanks to it, we are able to glimpse what Mount Wutai once was — quite different from what it is today," says Fan.

ALSO READ: Repairing the past, restoring our future

According to Zhong, much of the giant Buddha visitors see today is the result of repeated repairs and repainting over the past millennium — the dragon pattern on the robe was unmistakably from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). In fact, the Buddha lost both hands in earthquakes over the centuries, and they were only restored during a major repair effort led by the Dunhuang Academy in 1987.

"These efforts demand just as much — if not more — attention from the artists and artisans involved. The only difference is perhaps that, in the latter case, the reverence is directed more toward history," Fan says.

"For those intent on finding the most authentic Tang elements, they should look down as hard as they did up," says Zhong, noting that the Buddha's feet remain original to the Tang era. Generously shaped, they are as full and grounded as the boundless hope that must have stirred the hearts of those who toiled on the scaffolding — year after year, for 12 long years — to breathe life into this sublime vision.

Ma Jingna contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn