Academic finds great inspiration by delving into country's culture

Editor's note: As the People's Republic of China celebrates the 75th anniversary of its founding this year, China Daily asked prominent international figures to reflect on their relationship with the country and to talk of the direction in which they see it going.

"I'd been totally ignorant of China, more or less, through my education," Alan Macfarlane says.

Yet the 83-year-old anthropologist is now committed to building a cultural bridge between China and the West, through the exchange of shared enjoyment of culture.

An example of his commitment is the fact that, in addition to his titles of emeritus professor of anthropological science at the University of Cambridge and life fellow of King's College, he is guardian of a granite stone standing on the bank of the River Cam that commemorates the Chinese poet Xu Zhimo.

How is it possible to get to a closer understanding (of China)? You can read as many books as you like about a place, but unless you actually go there, meet the people, you really don’t get any strong impression.

Alan Macfarlane, UK anthropologist

Xu, who lived from 1897 to 1931, was an associate member of King's College for 18 months in the early 1920s. In 1928, he wrote his most famous poem, Saying Goodbye to Cambridge Again, which has been learned by millions of schoolchildren in China.

It was Macfarlane who set the stage for the installation of the stone, and who founded a poetry and art festival in the name of Xu that has brought together poets, literati, artists and scholars from around the world each year for the past 10 years, with the aim of promoting exchanges between East and West.

The festival is by no means Macfarlane's only project aimed at increasing understanding.

Cam Rivers Publishing, a company in Cambridge that Macfarlane co-founded with one of his Chinese students nine years ago, has been translating and publishing books by Chinese scholars in the United Kingdom and organizing exhibitions that feature influential local figures who have been deeply engaged with Chinese art, as well as hosting tea-tasting ceremonies that feature selections of fine Chinese teas.

Contemplating his journey, Macfarlane now realizes that one-third of his life has centered on China, and he says he knew little about the country before he turned 50.

His China story began in 1996 when he first undertook a visit to the country.

Understanding people

"How is it possible to get to a closer understanding (of China)?" he says. "You can read as many books as you like about a place, but unless you actually go there, meet the people, you really don't get any strong impression."

Macfarlane's first visit to the country was essentially as a tourist, but as an anthropologist who had been preoccupied with England, Nepal and Japan, his curiosity was aroused by wanting to compare the models of different civilizations and observe the contrast between East and West, as well as similarities caused largely by China's heavy historical influence in eastern and southern Asia and the commonalities of mankind.

"I suddenly realized that the later part of my life would perhaps be devoted to understanding China," Macfarlane says.

When he returned in 2002 the country's transformation amazed him.

The reform and opening-up, which jump-started China becoming an economic powerhouse, had entered its 25th year of implementation. And in 2001 the country being granted admission to the World Trade Organization and Beijing being granted the right to host the 2008 Olympic Summer Games had brought the country forward, into the limelight.

"From then on our love of China and interest in it… blossomed."

The great changes were appealing to Macfarlane, drawing him back to further explore the land, and the following 17 years gave him and his wife, Sarah Harrison, opportunities to visit China nearly every year until COVID-19 interrupted things.

Macfarlane traveled over almost all of the country, from megacities to remote counties surrounded by sweeping mountains.

He also talked to people from all walks of life, from local government officials in charge of running cities, to people from the Hui ethnic group, who sat by the side of the road playing mahjong. Scholars, musicians, Buddhist monks, his Chinese students and their family members all became his consultants on China.

The vastness of the landscape, the hugely varied culture, the hospitality of the people and the transformation that took place within the period of extraordinary growth were encompassed in travel diaries and photos taken by Harrison, with notes by Macfarlane.

However, for an anthropologist, traveling is much more than sightseeing.

Take an imaginative leap

Anthropology, after all, is a discipline that seeks to look far below the surface.

For example, a wedding in a certain region is not simply a ceremony but can signify characteristics of a specific social or cultural setting, Macfarlane says.

"When examining a wedding, if we ask the questions: Who did the bride marry? Was it a cousin or other relative? Then we are asking about social structure. If we ask what they wore and what religious and other rituals occurred we are asking more about culture. They are anatomically separable yet, obviously, closely related. So, anthropologists want to know not only what people do, but what significance their actions have."

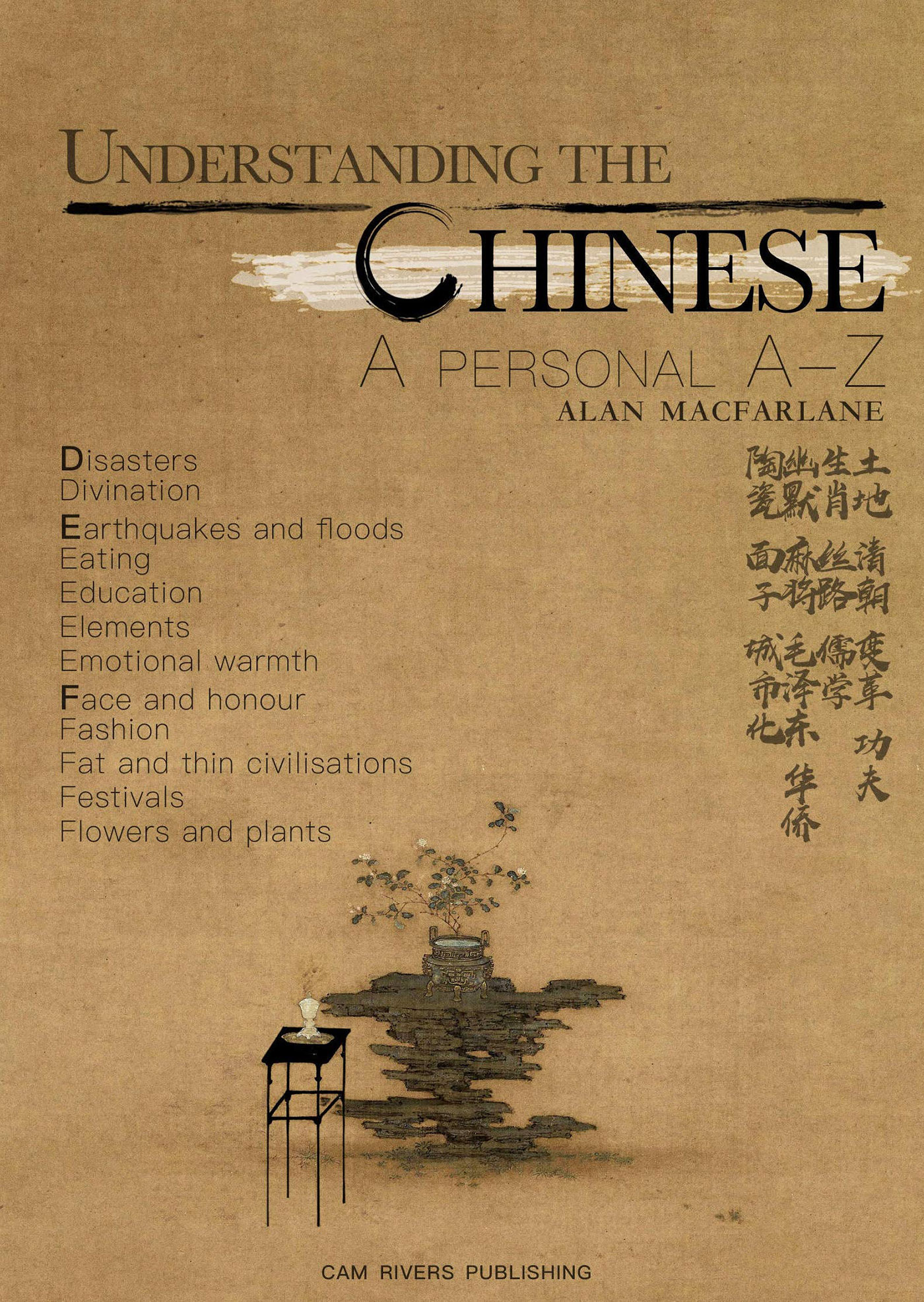

And to make sense of China based on his extensive tours, Macfarlane wrote the book Understanding the Chinese: A personal A-Z, which provides vignettes that explain more than 120 concepts of Chinese characteristics, including ancestors, Confucius, eating, education, law and justice, love and marriage, and more, including how people are presented in Chinese societies, how Chinese look at certain ideas, and how those perceptions have formed.

Macfarlane knows full well that writing a book about understanding the Chinese is attempting the impossible, and in the preface, he says, "Every assertion or generalization can be disputed, highly qualified or shown to be only a partial truth."

So he treated the analysis as if he were preparing a dictionary or encyclopedia, hoping to navigate readers toward the unfamiliar world of China but knowing it was a work in progress.

And seeking to get inside Chinese civilization has been an upside-down experience for him.

"China has been a huge challenge to all that I took to be normal and natural. My own view of my own Western culture and history has been totally transformed by my experience in China. This means that I have explored myself and my own culture in a Chinese mirror, as much as trying to see China in the Western, Nepalese and Japanese mirror."

Moment of change

The moment of change happens when one takes a step back, suspends some of the preconfigured categories and takes an imaginative leap, Macfarlane says, after which a person may find his or her innate way of thinking, is not particularly common, and the "cosmology" of others is not that outlandish, and is even worthy of attention.

And if there is no right or wrong, or strange or normal in cultures, ignorance and fear of others, and discrimination toward them, is unnecessary, he says.

The task that Macfarlane sets for himself is to lessen that fear or discrimination by explaining a little of how China works, so that the invisible barriers, which are built from taken-for-granted assumptions, can be visible.

"It's really about knowledge and communication. Once you get to know the other, you know why they're doing things, why things are different, and you begin to lose that fear. And the more communication, the more people visit China, the more the West appreciates its greatness, and the Chinese already, obviously, appreciate and have imported much from the West."

Macfarlane says he wishes he could act as a bridge between East and West, to forge cross-cultural understanding, because for him this is also "the aim of the greatest anthropologists".

On Sep 5 last year, Cambridge basked in sunshine as people came together in the heart of King's College in the name of the ninth Cambridge Xu Zhimo Poetry and Art Festival to celebrate exchanges.

Macfarlane writes in the preface for the event: "Chinese civilization is like a forest, where you have different trees: different people in different positions, different statuses and roles. Yet they all grow alongside each other and share the same space in a mutually supportive way … on the whole, not destroying each other. That kind of harmony seems to be a wonderful model for what the world could be."

Sitting on a bench in the warm daylight at the provost's private garden, where dwarf shrubs and a wildflower meadow grow in harmony, Macfarlane says: "Cultures and civilizations have to retain what is special about them, while at the same time living together and sharing what they can. So that's what I meant, that we will retain our different views on art, music, family systems, beliefs and philosophies. Because we need to. But that doesn't mean that we can't live in peace."