Relatives celebrate and build on incredible contribution of Canadian missionaries during a time of turmoil, Rena Li reports in Toronto.

Descendants of Canadian missionary families, who were students of the Canadian School in Chengdu, joined by members of the West China University of Medical Sciences Alumni Association, launch a special Legacy Project in October in Toronto to mark the 130th anniversary of the West China Hospital. (RENA LI / CHINA DAILY)

Descendants of Canadian missionary families, who were students of the Canadian School in Chengdu, joined by members of the West China University of Medical Sciences Alumni Association, launch a special Legacy Project in October in Toronto to mark the 130th anniversary of the West China Hospital. (RENA LI / CHINA DAILY)

These are love stories between Canadian missionary families and their Chinese roots spanning three centuries that should be remembered forever.

Making a difference

For the first time at an in-person event after two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, Marion Walmsley Walker, a 90-year-old mother and grandmother, brought three more descendants of the Kilborn family to celebrate the 130th anniversary of West China (Huaxi) Hospital. This was initially a small one-man clinic that Walker's grandfather Omar Leslie Kilborn (1867-1920) helped to set up in Chengdu, Sichuan province, and has become a world-renowned hospital.

The Kilborn family's relationship with China began in 1891, when Omar Kilborn joined the Canadian medical missionary work established in Sichuan. In the following 72 years, until 1963, three generations of the family got involved in the development of medical and educational undertakings in China.

Walker's mother Constance Kilborn was born in Sichuan and wished to follow in her father Omar Kilborn's footsteps. After she married Walker's father Lewis Calvin Walmsley in 1920, the couple traveled thousands of miles to China in 1921 to try to make a difference. Walmsley became the principal of the Canadian School for the children of the missionaries working in the West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Walker was born on the hospital campus and attended the school. Her father Walmsley had a good knowledge of Chinese culture. He studied classic Chinese literature and translated the poems of Tang Dynasty (618-907) poet Wang Wei. His interest in Chinese culture led him to take a position at the University of Toronto as a professor of East Asian Studies after the family returned to Canada.

"My father truly loved the great country of China and he spent his life developing that love in his students," Walker told China Daily. "He taught us to love and respect the land where many of us were born. He showed us the fabulous culture and poetry and beauty of China and we have never forgotten."

A photo from the exhibition Canadians in China — Old Photographs From Sichuan 1892-1952. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A photo from the exhibition Canadians in China — Old Photographs From Sichuan 1892-1952. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The descendants of the Kilborn family wish to have a legacy museum built in Canada to honor Omar Kilborn, Lewis Walmsley and all the other missionaries and their children in China.

After preparing for five years, Walker, along with Sun Jing, the president of West China University of Medical Sciences Alumni Association, launched a special Canadian School Legacy Project on Oct 26 in Toronto.

"An important purpose of this legacy is to help promote understanding and friendship between Canada and China," Walker said in a speech at the project launch event. "To accomplish these goals, we want to share knowledge of the Canadian School in China that sent almost 500 of its students to Canada, the United States and around the world as our informal ambassadors, and how the principal of the Canadian School in West China helped make this happen."

In addition to the fundraising from Canadian School children and the alumni association, Walker said she was so glad to hear that the West China Hospital of Sichuan University had decided to support the Legacy Project. The West China Hospital also agreed to support a second memorial for the Kilborn family by providing an agent to help search for a site in Picton Library in Prince Edward County.

"The Legacy in Picton will comprise a historical view of a school of Canadian students situated in Sichuan, China. It is a place to learn, allowing Canadians to get to know and understand the work of missionaries in China, a different country they appreciated and loved," Walker said.

And the fourth and fifth generations of the missionary families have taken up the baton of China-Canada friendship, continuing their family's love of China, according to Xiang Suzhen, a former official at Sichuan Foreign Affairs Office and now a volunteer of the Canadian School project.

The Kilborn family is just part of around 500 Canadian missionaries that went to western China from the late 19th century over the course of 60 years. They traveled up the Yangtze River and, with a focus on medical success, they built hospitals. West China Hospital is just one of them.

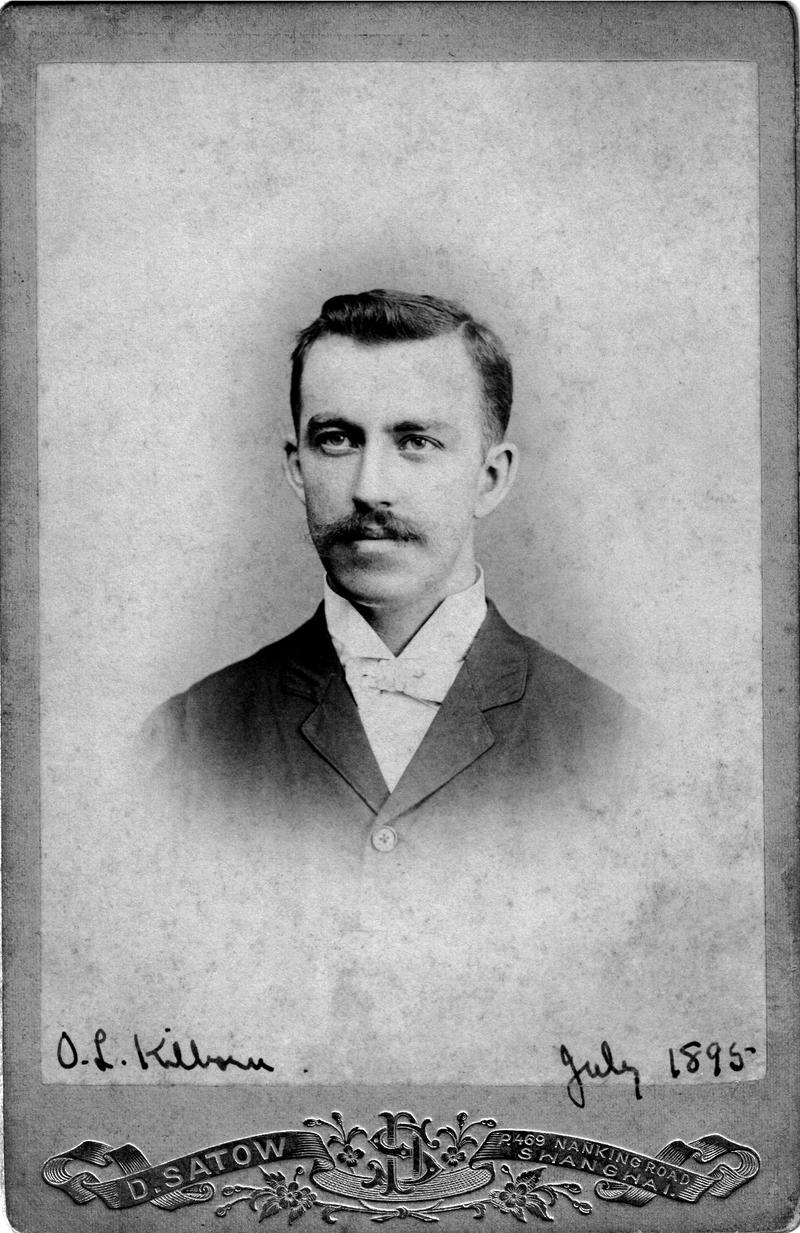

Doctor Omar Leslie Kilborn. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Doctor Omar Leslie Kilborn. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Pioneers' vision

Charles Winfield Service (1872-1930) is another man who left a legacy after living in Sichuan province for generations and devoted his whole life to Chinese medical education.

Service, who graduated as a surgeon from the University of Toronto, reached Chengdu in 1904 with his wife. He was appointed to a newly opened station at Leshan to resume the medical work there. His skill as a surgeon helped patients make an "excellent" recovery.

"He did much to establish the reputation of the missionary surgeon," according to Kenneth Beaton's Great Living, which is a brief biography of Service.

The West China Union University came into being through the vision of several pioneer missionaries in 1910. Omar Kilborn and Charles Service were prominent members of them.

"From the very opening, both of them anticipated that medicine would be taught," Beaton wrote.

In 1912, the Service couple moved to Chengdu to work in the mission hospital and the West China Union University. He was chiefly responsible for the hospital's work and lectured, in Chinese, in three subjects: surgery, gynecology and obstetrics. He translated most of the material as he went along.

In early March 1930, Service fell ill and needed an operation. Students had to do the operation following his own instructions, because there was no other surgeon in Chengdu. Unfortunately, Service died shortly on March 10,1930, after he had worked in China for 26 years. He was buried at the university.

Francie Service, the granddaughter of C. W. Service, told China Daily that it was her grandfather who was responsible for the first dental graduate in China, Huang Tianqi.

"When my grandfather Service met Huang Tianqi as a boy playing outside the hospital in Leshan, he was (so) impressed by Huang's intellect and character that he arranged for Huang to attend school and learn English," she said.

When Huang attended high school, he stayed with Charles Service and John Thompson, Francie Service's maternal grandfather, who was also a dental missionary in Sichuan. Huang became interested in healthcare and under C. W. Service's guidance, he trained as a medical assistant. After spending three years in the medical program, Huang officially registered as a dental student and in 1921, he was awarded the first dental degree in China. Thompson described the moment as the "proudest day" of his life.

Huang received the degree of doctor of dental surgery from the University of Toronto in 1927 with funding arranged by Thompson. Over the years, Huang and Thompson became trusted colleagues, and they worked together to expand the field of dental surgery in China.

"The teaching of dental surgery, by a well-trained Chinese professor, marked the successful diffusion of oral health knowledge and under the leadership of Huang, the foundation for sustainable dental care was established throughout China," says a memoir of the Service family.

Now a sculpture of doctors Huang and Thompson with a patient is displayed at China Museum of Stomatology in Sichuan University, Chengdu.

Francie Service said many second-generation members of the Service family have revisited their Chinese roots where their bicultural memories of residing in China were collocated with their current reality of being observers of modern China.

In May 1978, the Service family organized a tour to China. It was 30 years since Francie Service's parents Bill and Norma, who were both born in Chengdu, had been to China, and the family members still had a strong emotional connection to Chinese society.

"When I put my feet on the first step on Chinese soil, I felt it was my home," Francie Service told China Daily. "That's because of the love of China in my family. My mom and dad grew up there, they taught Chinese and they love China."

James G. Endicott and his wife, Mary Austin Endicott, on the Empress of China bound for Shanghai. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

James G. Endicott and his wife, Mary Austin Endicott, on the Empress of China bound for Shanghai. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Lifelong dedication

The Endicott family lived in Sichuan province for three generations, leaving another legacy to be remembered and celebrated. James Gareth Endicott (1898-1993), who was widely known by his Chinese name Wen Youzhang, was born in 1898 of Canadian missionary parents in Sichuan.

James Endicott worked in Chongqing from 1925 to 1940 and contributed greatly and bravely to the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45).

Marion Endicott, the granddaughter of James Endicott, said his grandfather tried to engage with Chinese people when he was young, but the beginning was not necessarily successful.

"As the Christians think their ideas better, they thought the Chinese are not going to go to heaven unless they understand about Jesus," Marion Endicott told China Daily.

According to Marion Endicott, during part of James Endicott's work for the US government in the 1940s, he began to meet with young Chinese communists, who were also engaged in the fight against the Japanese.

"In the process, my grandfather began to understand that Chiang Kai-shek was corrupt, and began to appreciate those communists — actually they were the ones who were going to save China. And so he supported them. And in supporting them, he also risked his own life to do so," Marion Endicott recalled.

After China's Civil War resumed in 1945, James Endicott became a strong supporter of the communists, and moved to Shanghai to publish an anti-Kuomintang Shanghai newsletter and provide underground help to Chinese progressive youth.

Marion Endicott revealed that her grandfather had a very special relationship with Zhou Enlai, who later became the first premier of New China. When it was time for James Endicott to leave China, he met with Zhou in Shanghai and asked what he could do to help. Zhou told him that "well, the main thing you could do is to help the West understand China and to understand what is coming to New China".

"So my grandfather dedicated the rest of his life to do that," said Marion Endicott. "And in addition to that, he focused on world peace. He was one of the leaders of the World Congress of Peace."

After returning to Canada in 1947, James Endicott founded and became chairman of the Canadian Peace Congress in 1949, when he hailed the founding the People's Republic of China. He also became a senior figure in the World Peace Council, serving as president of the International Institute for Peace from 1957 until 1971.

During the Cold War and for more than 40 years, James Endicott advocated understanding and friendship with New China. His advocacy led to public controversy with his church and Canadian government, which at one time considered putting him on trial for treason.

Before the end of James Endicott's life, the City of Toronto and York University all recognized him as one of Canada's prophetic voices in coming to terms with the march of history in Asia and for the possibility of peaceful coexistence between differing social systems. Shortly before he passed away in 1993, the Chinese government honored James Endicott with the People's Friendship Ambassador Award.

Transformation

According to Terrill B. Lautz, who studied the transformation of the protestant mission to China, the missionaries eventually became internationalists in reverse within Canadian society. They transitioned into international citizens along their journey, who became advocates of global interdependence encouraging Canadians to accept the fact that "we are living in a great bundle of nationhood nowadays", and the missionary's global humanitarian vision influenced their bicultural children for generations.

Paul M. Evans, a professor at the University of British Columbia, also found that the former China-based missionaries became "persuasive champions guiding the process of engagement with China, which was in sharp contrast to the American policy of isolation and containment" during the Cold War.

Canada normalized relations with the People's Republic of China in October 1970, and it was prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau's belief that China would become "one of the two or three most influential countries in the world". "For that reason, it must not be allowed to assume that it is without friends," Paul Evans wrote in his book Engaging China.

Charles Service had expressed a similar sentiment 50 years earlier than Trudeau. He concluded that "there is no doubt" that the Chinese "possess an array of qualities which will someday place them in the forefront of nations" in an article in The Globe in 1920.

According to a book entitled Canadian School in West China, the bilateral negotiations between Canada and China were held in Stockholm over a 20-month period from 1968 to 1970, and the chief Canadian negotiator was an old China hand from the West China Mission, Robert Edmunds.

After the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1970, Ralph Edgar Collins, John C. Small and Arthur Menzies, all born in China to missionary parents, were appointed as the first three Canadian ambassadors to China during the period from 1971 to 1980.

Contact the writer at renali@chinadailyusa.com