After taking a risk by dropping out of school at the age of 16, two decades later, Yang Lan has crafted a comfortable life by playing, teaching and making guqin, Wang Ru reports.

Guqin player and craftsman Yang Lan plays the instrument during a gathering with friends in Nantong, Jiangsu province, in 2021. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Guqin player and craftsman Yang Lan plays the instrument during a gathering with friends in Nantong, Jiangsu province, in 2021. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

When Yang Lan first became attracted to guqin, a zither-like seven-stringed traditional Chinese instrument, he was 16 and he didn't really know much about it.

It was 2003 and a poetic scene in a film about swordsmen, in which a character plays the guqin in the mountains, struck a chord with the boy. Born in Anlong county, Guizhou province, where more than 66 percent of the county is mountainous, he has a special affection for mountains, and the scene intrigued him to learn more about the instrument.

Through learning, we can become sensitive to sounds, and aware of the differences between musical tones. Since the music is created through our movements, we can also become more sensitive to ourselves.

Yang Lan, guqin player, teacher and maker

Guqin has existed for over 3,000 years and represents China's foremost solo musical instrument tradition. In the same year that Yang developed an interest in it, guqin music was proclaimed as an oral and intangible heritage of humanity by UNESCO.

Yang got to know legends related to the instrument, like how ancient thinker and writer Ji Kang of the Three Kingdoms (220-280) period played Guangling San, a guqin composition, before his execution and announced it would be lost forever.

The boy was further attracted by the cultural connotations of the ancient instrument, though he admits the attraction is more about imagination, instead of the instrument itself.

But the imagination really established a relationship between him and guqin. After years of exploration, he finally makes a living by playing and making guqin, and he has just published a book about his experience with the instrument.

At 16, shortly after his epiphany, Yang decided to drop out of school and pursue a music career. He had learned to play guitar, and told his parents he would go to Beijing and become a rock musician. But, in his heart, he wanted to move to Shaolin Temple located at the foot of the Songshan Mountain in Central China's Henan province to learn guqin, a place which perfectly matched the scenes in the film that initially attracted him to the instrument.

His parents were bitterly opposed to him quitting school, but they could not persuade the boy, who was resolute, and eventually gave way. In the autumn of that year, Yang left home and embarked on a life as a wanderer.

"You don't consider the consequences of your decisions at 16. I was simply attracted by something and drawn to start a journey to find it," says Yang.

Yang's new book, Qinren (Guqin Player), introduces his experience with the instrument. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Yang's new book, Qinren (Guqin Player), introduces his experience with the instrument. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

After nearly 20 years, Yang, now 35, says he does not regret his choice as he's satisfied with his current life, but, sometimes, he feels curious about how his life would have turned out if he had taken another path.

"He is very independent, a little rebellious, and has his own understanding of the world," says Le Shenme, a friend of Yang.

He bought a guqin in Shijiazhuang, Hebei province, and then went to Shaolin Temple where he was introduced to martial arts by a Buddhist surnamed Wu. Life there was so different from what he had imagined, that, several times, he expressed a wish to leave, but Wu persuaded him otherwise.

In his spare time, he explored the instrument he bought. He got in touch with a man who made guqin in Luoyang, Henan, and decided to visit him. The following summer, he left Shaolin Temple for Luoyang, and spent half a year there learning how to make guqin.

At the end of 2004, he went back home and tried to make guqin by himself, but didn't manage to complete one. In 2005, his father died in a traffic accident, and Yang plunged himself into a sea of books to dispel his grief. He records in his book how, since his mother had nearly no demands beyond him being happy, he became more free.

"That seems to be a keystone for my later life, which, ever since, has all been about freedom," says Yang.

In 2009, when he was invited by a friend to go to Ningbo, Zhejiang province, he agreed and took on the journey, carrying tools to make guqin and some books he liked.

He made a concerted effort to learn playing and making guqin by himself. He first learned to read guqin score, then he found audio of the pieces of music he wanted to play, trying to perfect them by reading scores and imitating the audio.

This way of learning guqin is quite different from the traditional method. In the old days, guqin was taught face-to-face-literally. The teacher and student sat opposite each other. They created a part of melody together, without going ahead to the next part until the student could play as well as the teacher.

According to a book written by guqin master Yang Zongji (1863-1932), he learned a piece of music by playing it nearly 1,000 times with his teacher Huang Mianzhi.

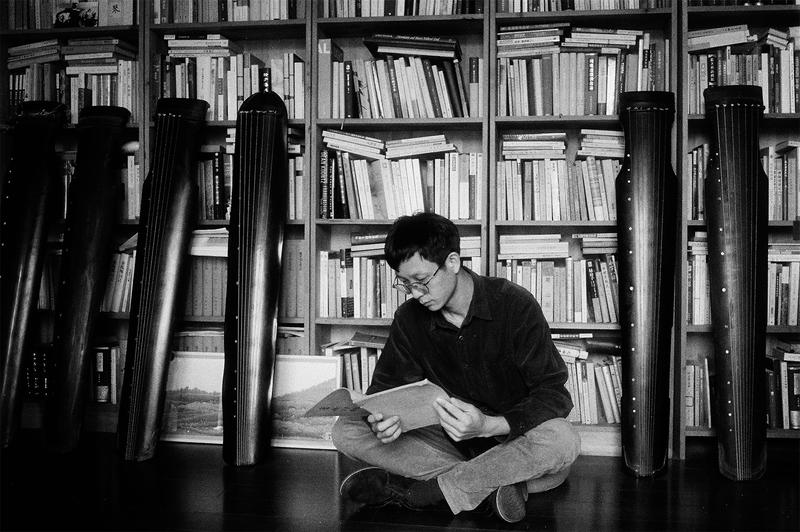

Yang reads a book at home in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Yang reads a book at home in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Later, Yang Lan found that he met difficulties. Different from the scores for some Western instruments, which record the melody and rhythm of the music, the score for guqin only records the fingering.

"You can see a guqin score as an exposition, full of descriptions about where to put your fingers and which string you should pluck, but it doesn't tell you the result of the fingering, no melody or rhythm. No one knows how the music actually sounded in ancient times.

"So the score offers the player a lot of freedom. Mature players can create music according to their unique understanding based on experience, and don't need to follow a composer. But for a beginner, there's a big obstacle," says Yang Lan.

Probably because of the freedom allowed in playing old pieces of music, guqin players don't often create new ones, but prefer practicing the older compositions in different styles, Yang Lan suggests. "From ancient times to today, altogether there are only about 600 pieces of guqin music," he says.

Luckily, after moving to Hangzhou, Zhejiang, in 2011, he was introduced to modern guqin master Cheng Gongliang, who corrected his way of playing and inspired him to better understand the music and the instrument. He also began to make guqin, gradually earning a living by doing so.

"The craft of making guqin is not very complicated. The most difficult part is to identify the unique musical tone of the instrument you're making, which requires a lot of time and experience," says Yang Lan.

Although he received guidance from various people at different stages of his life, he has mainly learned to play and make guqin by himself. In his eyes, being self-taught is very important.

"Although I left school before I even graduated from junior high school, I learned by myself later. I believe that it is the most important way of receiving education, and we should continue to learn throughout our lives.

"At the end of the day, even with good teachers or education systems, the core of understanding knowledge is to establish our own feeling of it, and then receive its feedback to us, so that we can really master it. That is not different from being self-taught," says Yang Lan.

He adds that self-education requires a person to have a clear understanding of themselves, and be able to work as both a student and a teacher who can supervise themselves.

But he also admits there are risks of quitting school at a young age. "Such a choice is dangerous. It was a fluke that I didn't become self-indulgent. Since I left school, I was lucky enough to meet different people in my life to guide me."

In the eyes of Le, Yang Lan is talented. "He has good instinct when searching for what he really likes and finding those who can help him."

He also teaches guqin now, and that has urged him to consider what people can gain from learning it.

He says there have been very few professional guqin players throughout history. In fact, it was mostly members of the literati who became well-known for playing it.

"So the main object, from my perspective, is to receive and deliver an aesthetic education. Through learning, we can become sensitive to sounds, and aware of the differences between musical tones. Since the music is created through our movements, we can also become more sensitive to ourselves," says Yang Lan.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn