A woman cares her newborn baby, who is wearing a face shield, in the Neonatology unit of the Mexico Hospital in San Jose, Costa Rica, on April 28, 2020, following the implementation of strict measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. (EZEQUIEL BECERRA / AFP)

A woman cares her newborn baby, who is wearing a face shield, in the Neonatology unit of the Mexico Hospital in San Jose, Costa Rica, on April 28, 2020, following the implementation of strict measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. (EZEQUIEL BECERRA / AFP)

More than a year since the global pandemic struck, its damage to population growth is starting to become starkly clear, and not just because of the grim death toll.

Major economies from Italy to Singapore, already afflicted by dire demographics, are seeing that phenomenon accelerate after measures limiting social contacts and the worst growth crisis in generations combined to prevent or dissuade people from having babies.

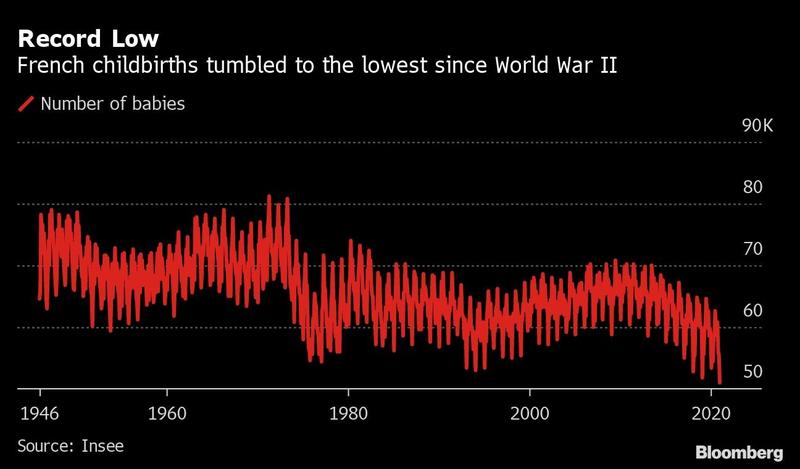

While workplace closures and forced isolation might have encouraged couples to spend time together productively, the number of newborns has been dwarfed by plunging fertility emerging in national data for 2020. For instance, France saw its lowest birth rate since World War II.

Falling population growth will hurt potential growth (as the labor force falls), hurting tax revenues. And this will occur concurrently with increased spending on public pensions and healthcare.

Sonal Varma, an economist at Nomura Holdings Inc

ALSO READ: South Korea's fertility rate falls to lowest in the world

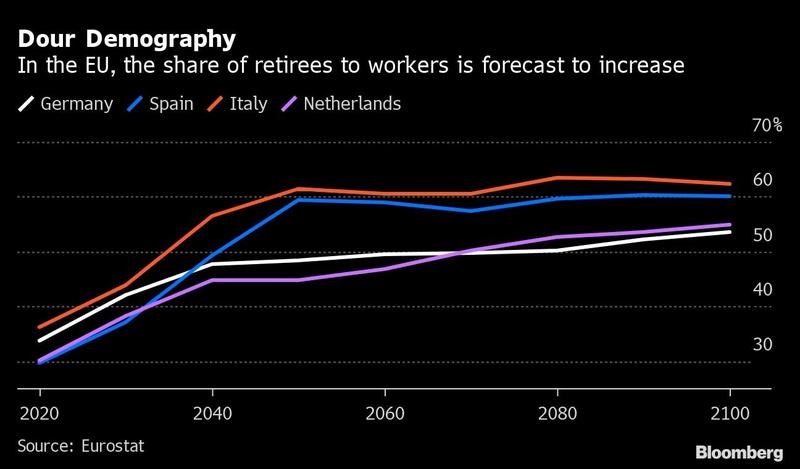

That points to a potentially ruinous legacy of the crisis. Not only have governments racked up enormous borrowings to fund economic aid, but the supply of future taxpayers to service that debt and fund public pension systems now looks even thinner than it was. Such a blow would be particularly crippling in parts of Asia and Europe with aging populations.

“The longer and more severe the recession, the steeper the fall in birth rates, and the more likely it is that a fall in birth rates becomes a permanent change in family planning,” said HSBC Holdings Plc economist James Pomeroy. If his forecasts pan out, “it’s going to lower potential growth rates and it makes high levels of debt less sustainable in the long term.”

Within two decades, 10 percent to 15 percent fewer adults may join the workforce, according to Pomeroy’s calculations. He reckons a recent projection by demographers at the Lancet journal for the world’s population to start shrinking in the 2060s already risks looking obsolete, with an inflection a decade sooner.

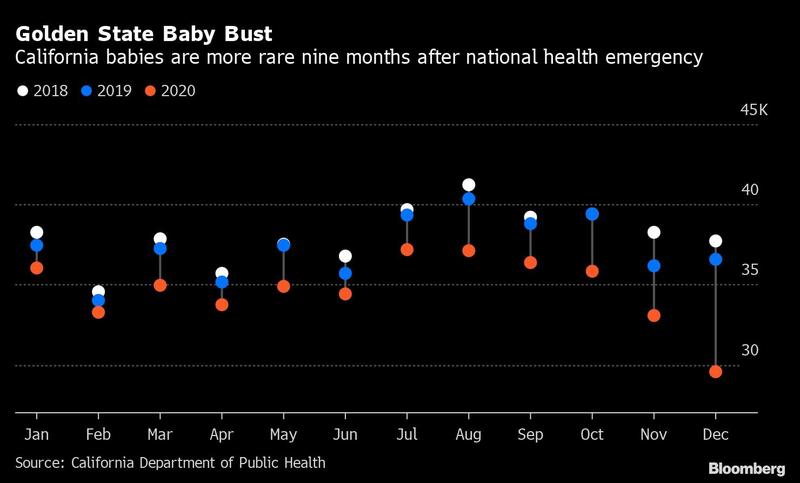

A dropping birth rate is particularly evident in Italy, one of the first outbreak hotspots. Births in 15 cities there plummeted 22 percent in December, exactly nine months after the pandemic struck. Comparable effects are appearing elsewhere, such as in Japan, which saw the fewest newborns on record in 2020.

Fiscally speaking, such outcomes are ominous. In the US for example, even without the effects of the pandemic, retirees are due to outnumber children by the 2030s.

In the European Union, the ratio of people over 65 to those aged 15-64, a key metric on the affordability of social services for the old, will probably deteriorate. That would exacerbate a situation that was already worsening, with pension spending rising by nearly a third between 2008 and 2016.

“The fiscal impact can be a double whammy,” said Sonal Varma, an economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. “Falling population growth will hurt potential growth (as the labor force falls), hurting tax revenues. And this will occur concurrently with increased spending on public pensions and healthcare.”

READ MORE: Virus worsens Europe's inequalities in another way - fertility gap

Lower birthrates have also vastly outweighed whatever effect could have resulted from existing couples being kept indoors and in each other’s company. In one outlier of fertility, six women in a single street in the English city of Bristol became concurrently pregnant in 2020, according to the BBC.

Even if vaccine drives are successful in taming the virus’ spread, the economic fallout, such as joblessness, is likely to last past the point where the health crisis abates, with a corresponding brake on births.

Things might not necessarily improve when the economic data show a recovery, however, considering that fertility across major economies has steadily declined for decades.

The crisis has been most damaging for people in the prime childbearing ages of their 20s and 30s. Research by the Guttmacher Institute found the pandemic led more than 40 percent of women in the US to change plans about when to have children or how many to have.

A study published by Germany’s IZA–Institute of Labor Economics projected that the drop in US births will be 50 percent larger than during the 2008-09 crisis. Consultancy PWC predicts a “dramatic decline” in UK newborns this year.

Lockdowns have also physically prevented and hindered people from forming relationships that could ultimately lead to pregnancy.

“Almost nonexistent,” is how Sierra Reed, a 34-year-old Californian, describes her experience of dating last year once the pandemic hit. Even when lockdowns loosened, she stayed wary.

“There was a big part of me that was still super uncomfortable with being in spaces of people, without masks, and doing typical date activities like dining together,” she said.

As evidence of how the pandemic is delaying family formation, the number of marriages in Singapore sank about 10 percent in 2020. The government has boosted cash payments on offer to encourage citizens to have children despite the coronavirus.

What’s more worrisome for some countries now is that lower fertility will be hard to reverse in line with other economic healing.

READ MORE: NZ's birth rate lowest on record, deaths decrease in 2020

“When you start delaying births by a few years, it’s possible that some of those births will come back, but it’s possible that some of them aren’t” going to, said Phillip Levine, a professor of economics who analyzes childbearing data at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

Some births won’t occur “because the window for postponement is narrowing down,” said Tomas Sobotka, a fertility expert at the Vienna Institute of Demography in Austria.

“Many women and men who plan to have a baby in the future are now in their late 30s or early 40s, and likely to face infertility when trying to have a child later,” he said.