Sanitary workers prepare to perform a fumigation in an area in Yemen's southern coastal city of Aden on May 3, 2020, as part of a campaign to prevent insect-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and Chikungunya virus, amidst the pandemic. (PHOTO / AFP)

Sanitary workers prepare to perform a fumigation in an area in Yemen's southern coastal city of Aden on May 3, 2020, as part of a campaign to prevent insect-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and Chikungunya virus, amidst the pandemic. (PHOTO / AFP)

COVID-19 could result in thousands of deaths from malaria across the Pacific region, with health experts warning that the pandemic response could derail previously planned efforts to control the mosquito-borne disease.

Malaria continues to extract a heavy toll on human lives, killing more than 400,000 a year globally, with most of the victims being children under five. Africa, Asia, and the Pacific are particularly prone to the disease.

Tanya Russel, a research fellow at the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine at James Cook University in Cairns, said the biggest threat is the delay in implementing malaria control programs.

"These programs are time sensitive," she noted. "Any delay is a serious concern as malaria jumps very quickly."

The biggest issue has been lockdowns, which have "hampered the ability of teams to get out to the villages and more isolated places with the malaria eradication program", Russel said.

The Solomon Islands is one of the highest malaria-burdened countries outside Africa and a key focus area in the Pacific.

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Rick Houenipwela told members of the Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance and Asia Pacific Malaria Elimination Network in September: "Malaria has ravaged my people since the beginning of time”.

Tanya Russel, a research fellow at the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine at James Cook University in Cairns, said the biggest threat is the delay in implementing malaria control programs

ALSO READ: WHO: Malaria to kill more than virus in sub-Saharan Africa

He said two strains of malaria are present within the Solomon Islands-Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. The latter is the most dangerous of the human strains of malaria, and can be fatal if treatment is delayed more than 24 hours after the onset of clinical symptoms.

Brendan Crabb, chair of health welfare organization Pacific Friends of Global Health and chief executive of the Melbourne-based Burnet Institute, said the Pacific is at acute risk if intervention measures are disrupted within health systems currently overwhelmed by, or focused on, COVID-19.

"There are a number of infectious diseases that could spike if we ignore them in the wake of the focus on COVID-19, but none are more acute than the short-term risk that malaria poses," he told The Guardian.

READ MORE: WHO warns malaria deaths in Africa could double this year

"It can double, even triple or worse, in a single season if the wheels come off control measures."

In Papua New Guinea, where malaria remains endemic, case numbers surged between 2001 and 2016-from 80,000 to 500,000-when control measures weakened.

A recent study published in the medical journal The Lancet said disruptions to malaria interventions could lead to 46 million additional cases worldwide.

Of all infectious diseases, malaria can explode the fastest.

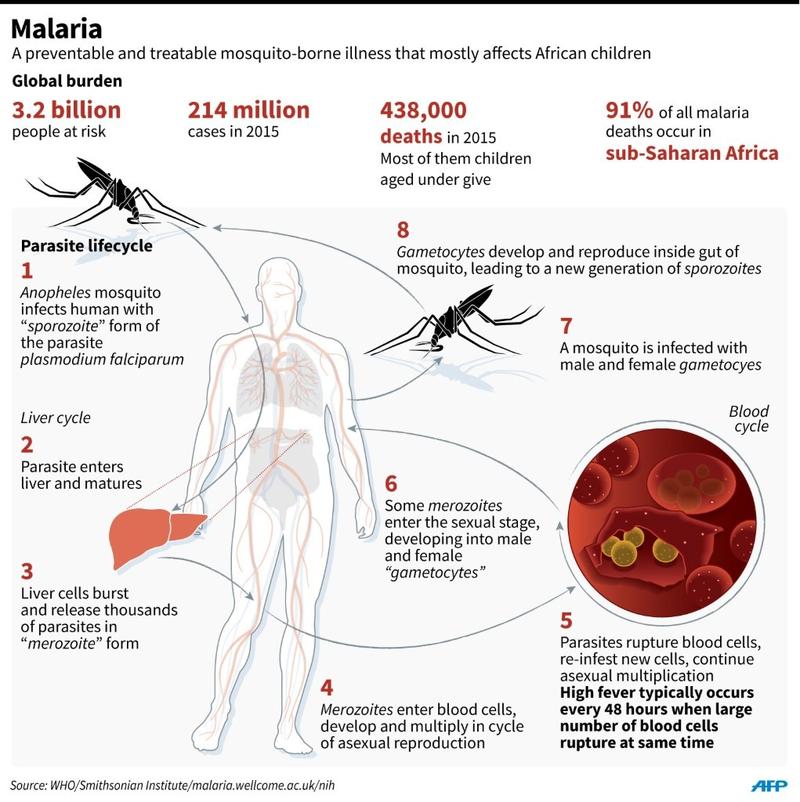

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. It is preventable and curable, says the World Health Organization.

The WHO says that in 2019, there were an estimated 229 million cases of malaria worldwide and that the number of malaria deaths stood at 409,000.

Children under age five are the most vulnerable group affected by the disease. In 2019, they accounted for 67 percent of all malaria deaths worldwide.

Total funding for malaria control and elimination reached an estimated $3 billion in 2019. Contributions from governments of endemic countries amounted to $900 million, representing 31 percent of total funding, according to the WHO.

Direct impacts

Stephen Rogerson, an infectious diseases expert at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at the University of Melbourne, said the direct impacts of COVID-19 in most countries in the region have been "relatively small".

"But I have not seen data on the indirect impacts on diseases like malaria," the professor said.

"Some of the impacts could take quite some time to manifest. Impacts of scaling back malaria control may take some time to be evident in case numbers or mortality," he said.

Rogerson said effects on malaria control programs due to redeployment of staff to coronavirus-related work is one obvious concern, while reduced health facility utilization by malaria-infected adults and children is another.

A report published recently in medical journal BMC Medicine has noted that "relatively little attention has been paid to understanding how the pandemic has affected treatment, prevention and control of malaria, which is a major cause of death and disease and predominantly affects people in less well-resourced settings".

The report said successes in malaria control over the past five years had reduced the global malaria burden.

But the gains are "fragile" and progress in the eradication of malaria has stalled, the report warned.