The winner of BMW Art Journey 2020, sculptor LeeLee Chan will travel around the world, studying the evolution of material cultures and community-engaged art. Chitralekha Basu reports from Hong Kong.

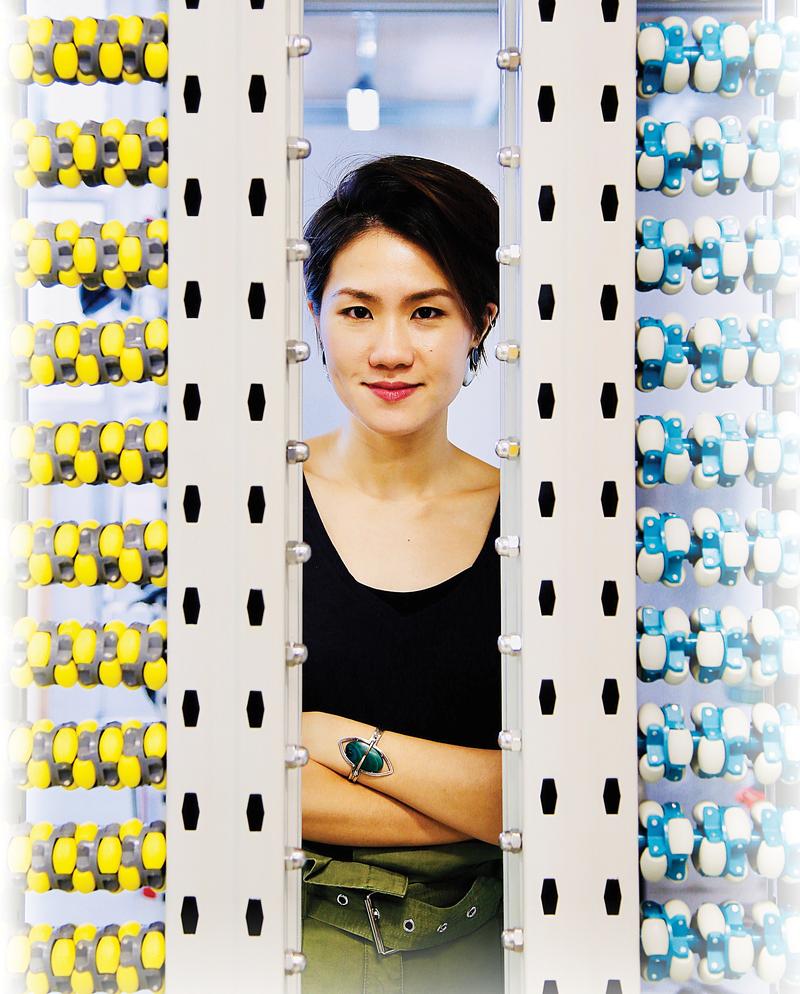

LeeLee Chan flanked by the columns of her Blindfold Receptor sculpture and displaying pieces of broken astroturf which are potential material for her creations. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

LeeLee Chan flanked by the columns of her Blindfold Receptor sculpture and displaying pieces of broken astroturf which are potential material for her creations. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

LeeLee Chan could have been in Japan by now, checking out plastic pallet manufacturing bases, or perhaps in Pulpi Geode in Spain, or maybe even in a concrete research institute in Switzerland, watching how bacteria embedded in concrete can be made to repair cracks.

Chan is the winner of BMW Art Journey 2020. Launched in 2015 by the luxury-car manufacturing brand and Art Basel, the generous annual award sponsors an artist’s touring of proposed destinations around the world with a view to enhancing their artistic philosophy and helping to develop their practice. By August end, Chan would have begun her travels across three continents, following a trajectory that nearly circles the globe, had it not been for COVID-19 which has practically ruled out international travel.

Chan’s winning proposal, titled “Tokens from Time”, aims to trace some of the materials used in her sculptures — crystal and silver, for instance — back to their source and experience them in their raw, organic forms. At the same time Chan is interested in how craftsmanship — from the ancient times down to her own — has left its imprint on such materials and helped build communities around them.

Construction lights and crystals from a scavenged chandelier figure in LeeLee Chan’s Sunset Capsule, shown in UCCA Dune in Beidaihe, China. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Construction lights and crystals from a scavenged chandelier figure in LeeLee Chan’s Sunset Capsule, shown in UCCA Dune in Beidaihe, China. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Her wish to visit the silver mines in Mexico was inspired by the history of revival of pre-Columbian silver designs in Taxco by the American designer William Spratling in 1931. “He brought his modernist ideas to Mexico, setting up workshops and hiring hundreds of silversmiths from across the country who were encouraged to freely express their ideas, creating designs truly unique to Mexican culture,” says Chan.

“I am interested in the ways in which value and desire are projected,” Chan says. For instance, crystals are ascribed different values depending on their use, she notes. They could be “fetishized as lifestyle products,” made to serve as a vital component in computers and phones, and could also be split into nano crystals which have a variety of industrial use, including as flexible substrates in solar panels.

“I think it could be interesting to trace the journey of crystals from being an organic form to nano crystals,” Chan says. She has plans to go to Germany to have a close look at the application of nanotechnology on metal — the sort “they are using to make airplanes lighter.”

Detail from Pallet in Repose (Marine), from a 2019 Capsule Shanghai exhibition. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Detail from Pallet in Repose (Marine), from a 2019 Capsule Shanghai exhibition. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Things no one wants

She has a fondness for using inexpensive materials of everyday use that most often get binned after serving their purpose — plastic pallets used for ease of moving stuff around in logistics establishments, for example. An upright pallet in her Pallet in Repose (Marine) installation was the centerpiece at a Capsule Shanghai gallery-hosted exhibition in 2019 — a solitary giant among hundreds of much-smaller metal hardware pieces strewn all around, like a crowd on a beach, unrelated and aloof.

The idea is to invest mass-produced and recyclable stuff with meaning, dignity even. “For me, making a sculpture is a process in discovery. When I finish working on a piece of material, I see it in a completely different light. And that process is very humbling,” says Chan who sees herself as a mediator between objects and her audience — as someone trying to open up newer possibilities of seeing things that could be antithetical or unrelated to the way they appear at first.

LeeLee Chan flanked by the columns of her Blindfold Receptor sculpture and displaying pieces of broken astroturf which are potential material for her creations. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

LeeLee Chan flanked by the columns of her Blindfold Receptor sculpture and displaying pieces of broken astroturf which are potential material for her creations. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Her sculptures can look huge and imposing but most often they are made of flimsy material, picked up from the roadside. For instance, in a piece called Protector, Chan used egg packaging material, a car windshield and also mother of pearl tiles. “So all the objects used in it are meant to protect things. The sculpture looks like a totem pole that is monumental and carved out of stone. But it’s actually Styrofoam and super light,” says the artist.

Chan’s Blindfold Receptor comprises two sets of metal columns shooting upwards. The wheels are placed on, rather than under, the narrow base. Seen from a distance, the sculpture can look like elongated bird feet with talons from a mechanized future. Chan says the piece represents a hybrid of natural and mechanized elements. It was inspired by a New York Times article which mentioned caterpillars being able to sense the color of their surroundings through their skin and changing their own body color accordingly. Apparently the caterpillars were blindfolded during the experiment leading to the conclusion.

“So I was struck by the contrast that while we human beings end up changing the environment by excessive use of technology, getting more disconnected from our bodies in the process; caterpillars have adapted to the Anthropocene environment by developing a mechanism to sense color through their skin,” says Chan.

A piece of broken concrete collected from a car park could be turned into a work of art by Chan. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

A piece of broken concrete collected from a car park could be turned into a work of art by Chan. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Once she had finished reading the article, Chan’s eyes fell on the grooved columns of metal frame storage racks used to hold height adjustable shelves in her studio and subsequently on the high-rise public housing buildings away in the distance outside the window of her Kwai Chung studio. “I saw a connection between these three unrelated things and wanted to make a sculpture based on the idea,” Chan says.

The series of rollers between the columns were covered with clay, spray-painted in caterpillar colors. The wheels came from trolleys used in logistics companies. So on one hand, the sculpture, as Chan points out, embodies a process of evolution from wheels to a roller conveyor system, while on the other it draws attention to “caterpillars camouflaging themselves as protection against human beings destroying their environment.”

LeeLee Chan paints clay units like the ones used in her Blindfold Receptor sculpture. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

LeeLee Chan paints clay units like the ones used in her Blindfold Receptor sculpture. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Eco-friendly art?

Although Chan uses a lot of scrap and found objects — pieces of broken asphalt, arranged like a circle on a wall, in a sculpture called Absorber #2 shown at Hong Kong’s Duddell’s, for example — she is reluctant to call herself a crusader for environmental protection and sustainability issues.

“As an individual I try to be responsible in my behavior towards the environment as far as I can. But I don’t see myself as an environmental activist,” Chan says, noting that some of the materials used in her works, like concrete and resin are not bio-degradable. “But I try to strike a balance. Instead of buying new polystyrene or Styrofoam, I use recycled material.”

“I find it interesting to use structured material to build organically. If I had the choice of using more environment-friendly material I will go for it,” she adds. At the same time, Chan would prefer not to have to worry about whether every piece of material used in her sculptures is environment-friendly.

Rejected materials, such as the astroturf uprooted from this tennis court, tend to trigger LeeLee Chan’s creative impulses. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Rejected materials, such as the astroturf uprooted from this tennis court, tend to trigger LeeLee Chan’s creative impulses. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Chan came back to Hong Kong after thirteen years in the United States, where she had moved to study fine art — first at the School of Art Institute of Chicago, followed by the Rhode Island School of Design from where she received her MFA in painting. One of the reasons for her return was to be able to inherit some of the knowledge and skill sets of her parents, who are experts in Chinese antiquity. As she awaits the lifting of travel restrictions to embark on her journey in search of the materials and people whose lives they touch, Chan remains firmly anchored in her native soil, assured in the knowledge that Hong Kong is where she would like to stay and continue to make her art.

ALSO READ: Sculpting in time