Epang Palace was neither completed nor destroyed by fire, but instead, meticulously built on a drained lake bed, report Wang Ru and Qin Feng in Xi'an.

In 2004, a groundbreaking discovery shocked the public: archaeologists excavating the foundations of the Epang Palace site, in Xi'an, Shaanxi province, announced they had discovered that the legendary complex had never been completed. Furthermore, they concluded that the story that the palace had been torched by the late Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) warlord Xiang Yu was, in fact, false.

Tang Dynasty (618-907) poet Du Mu described the splendor of Epang Palace, which was commissioned by China's first emperor, Qinshihuang, who established the Qin Dynasty.

Du said that to build the grand and luxurious complex, the emperor drove his laborers to extremes, leading to widespread unrest that ultimately contributed to the downfall of the dynasty. Eventually, Xiang burned the complex in a symbolic act of rebellion. The complex thus became a lesson for later rulers not to pursue monumental constructions at the cost of people's welfare.

READ MORE: A plain that echoes with legends

Du's article was influential and widely quoted. When archaeological discoveries suggested that the dreamlike palace had never been completed, many found it hard to accept. But with concrete archaeological evidence, the findings became widely accepted facts in academia.

Studies on the Qin complex have never ceased. Recently, archaeologists announced their latest discoveries at the site. They revealed that it was initially built on the silt at the bottom of a drained lake, which also shed light on the construction management of large-scale projects during the Qin era.

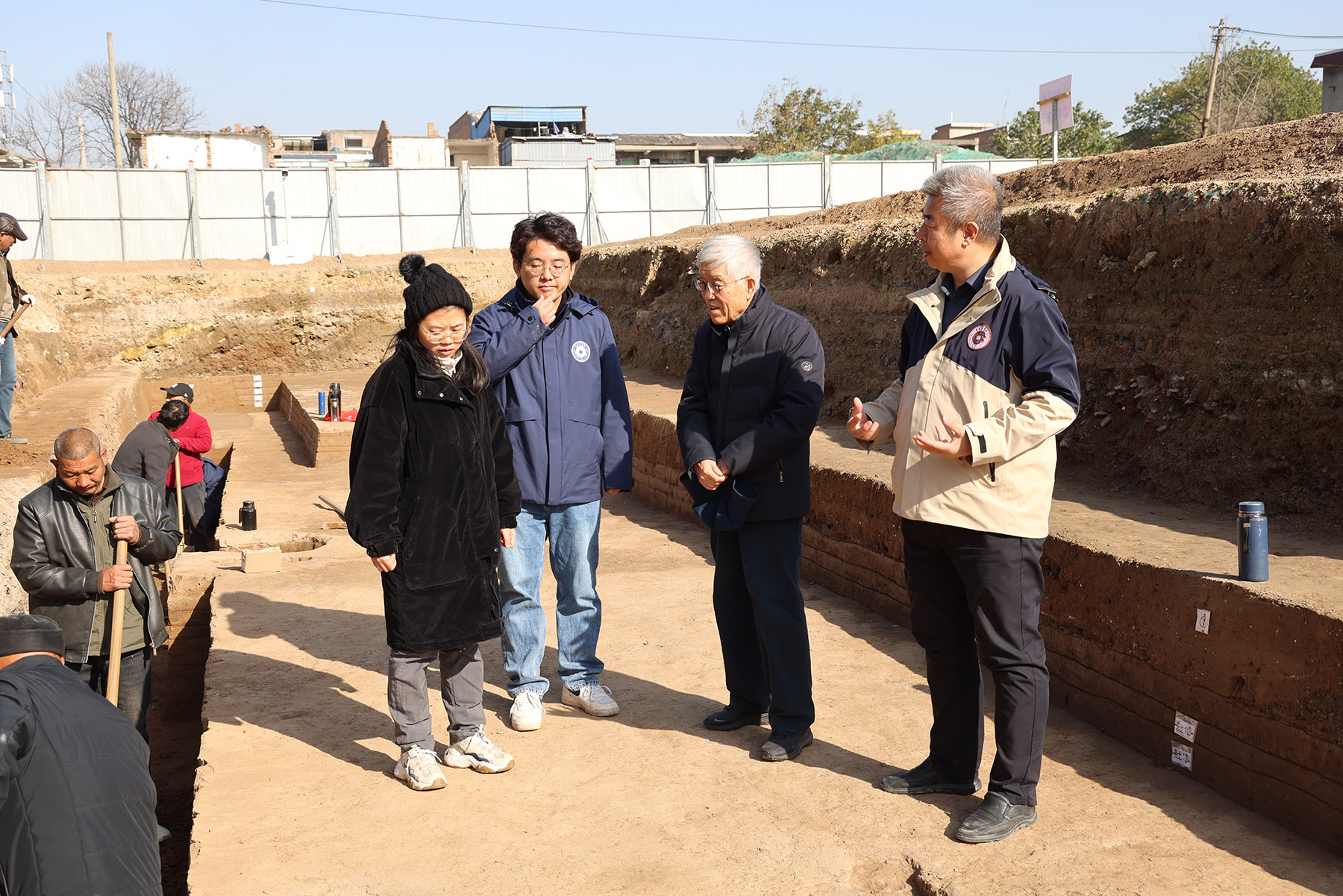

Liu Rui, head of the archaeological team at the Epang Palace site and a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of Archaeology, says the work last year was carried out from September to December, with the aim of verifying whether the complex was built at the bottom of a drained lake, which they first suspected about a decade ago.

Archaeologists discovered widespread silt deposits beneath the foundations of the palace, along with traces of artificial clearing, confirming the initial guess that the palace was built on a drained lake, a phenomenon that had never been seen before at other palace sites of a similar date. To people's surprise, the silt deposits petered out a short distance to the north of the site, indicating that more suitable construction areas were available nearby. Why then was a lake bed — with all the complexities of construction — used instead of firmer ground?

"Historical records indicate that the Qin people revered the virtues of water. We guess they deliberately built the complex at the bottom of the drained lake. Looking back on the construction of Emperor Qinshihuang's mausoleum, we know it had a giant water control system, which means the mausoleum was also built somewhere rich in water. Maybe the emperor just preferred locations with abundant water resources, but that decision did significantly increase the earthworks for the palace's construction," says Liu.

Archaeologists further found that the complex seemed to have a north-south central axis, which evenly divided the whole Guanzhong Plain into two halves. The choice of the location may also be related to the emperor's wish to build the complex on the axis, Liu says.

Qin laborers might have drained the lake first, followed by treating the underlying silt to achieve a relatively uniform thickness. After this, foundation ramming was carried out in sections.

He Jiahuan, another member of the archaeological team, says they initially thought the rammed earth platform of the palace, which is about 1,270 meters long and 420 meters wide, was rammed as a single, uniform structure, but their studies suggest that the platform was rammed in sections.

"Vertically, the foundation was layered: the lower layer was rammed first, followed by the upper layer. Horizontally, it was constructed in sections. For example, the southern section was rammed first, followed by the northern section. Thus, the entire foundation was essentially built layer by layer and section by section through ramming," says He.

He says this approach allowed the quality of the construction work to be better controlled, but managing the construction was more demanding.

"Adopting this approach, people must maintain the sequential order of each section and coordinate the progress of each part. It is essential to ensure that no section is completed before another has started, avoiding any gaps in the workflow. The entire construction management system requires a high level of precision and organization," says He.

The quality of their work can also be traced from the remaining rammed earth, which Liu says was of very high quality. "The earth was remarkably clean, containing few pottery pieces, which means it must have been carefully selected before use. The rammed earth layers were also uniform in thickness, and they were rammed to be particularly solid and hard," says Liu.

"The highest point of the platform stood over 9 meters above the ground, signifying a huge earthwork at that time. We have found that the construction teams had clear tasks and divisions of labor, working on the platform in segmented sections. It offers a rare glimpse into the management of large construction projects in the Qin era," says Liu.

Historical literature shows that in 212 BC,Emperor Qinshihuang thought that the Xianyang Palace he was using was relatively small in comparison to the size of the populous capital Xianyang. He ordered the construction of another imperial complex in the Shanglin Garden, a royal garden that was used from the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) to the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). Altogether, he dispatched 700,000 men to construct his mausoleum and the Epang Palace.

Two years later, the legendary emperor died and construction was paused. Then, in 209 BC, the second emperor of the Qin Dynasty restarted building work to fulfill his father's wishes, but he, too, died two years later. With the downfall of the Qin Dynasty in 206 BC, the construction came to an end without completion.

Over decades, generations of archaeologists have confirmed the site to be that of the Epang Palace using multiple types of evidence. Official archaeological efforts on the site started in 1994. From 2002 to 2008, through coring and excavation, archaeologists clarified its scope and the fact that it was neither completed nor set on fire. Since 2015, archaeologists have continued to learn more about the selection of the site and details of the complex's construction.

"We have continued our work on the site because it offers a good reference for many other Qin and Han constructions. It was a large construction project for which Qinshihuang chose the site and pushed for its development after Qin unified China. There are also clear date records in historical literature, so when studying other sites that lack evidence of dates and times, we can make comparisons with this one," says Liu.

During the following dynasties, the name of Epang Palace continued to appear in literature, but whether these references relate to the same site or another site remains to be seen. The latest discovery of five small Tang Dynasty tombs within the excavation area indicates that the site was possibly used as a cemetery for lower-level tombs during the Tang era.

Liu says the poet Du's description of the Epang Palace's splendor must have been false."Du couldn't have seen ruins of splendid architecture during the Tang period," he says.

ALSO READ: Framing a viewpoint

"In another of his articles, he explained that his vivid depiction of a magnificent Epang Palace was drawn from historical imagination — a literary device intended to satirize Emperor Jing of the Tang Dynasty at the time, who, much like Emperor Qinshihuang, indulged in lavish construction after ascending the throne."

"Through our work, Epang Palace is emerging from its legendary image, revealing itself once again to the world in its true, intricate, and astonishingly engineered form," he adds.

Contact the writers at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn