An exhibition of works by Chao Shao-an at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum celebrates the distinctive practice of the artist and instructor, while also highlighting his life-long commitment to promoting Lingnan-style art. Wang Linyan reports.

Standing in front of a scroll painting showing a white peacock perched on a gingko tree, artist Susan Ho Fung-lin draws attention to its minute details and the process involved in making it come alive.

“Note the colors in between the feathers,” she says, explaining that the artist would have needed to moisten the entire figure of the peacock every time he added a layer of color, and that would have been “at least three times”.

READ MORE: Brushstrokes of legacy

The painting in question is a masterpiece by Ho’s teacher Chao Shao-an (1905-98), a stalwart of the Lingnan school of painting — an early 20th-century art movement that sought to modernize Chinese painting by incorporating features from artistic developments in other cultures. White Peacock (1969) is part of an ongoing retrospective exhibition titled Legacy of Lingnan School of Painting in Commemoration of the 120th Anniversary of the Birth of Chao Shao-an at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum (HKHM).

Masterful strokes

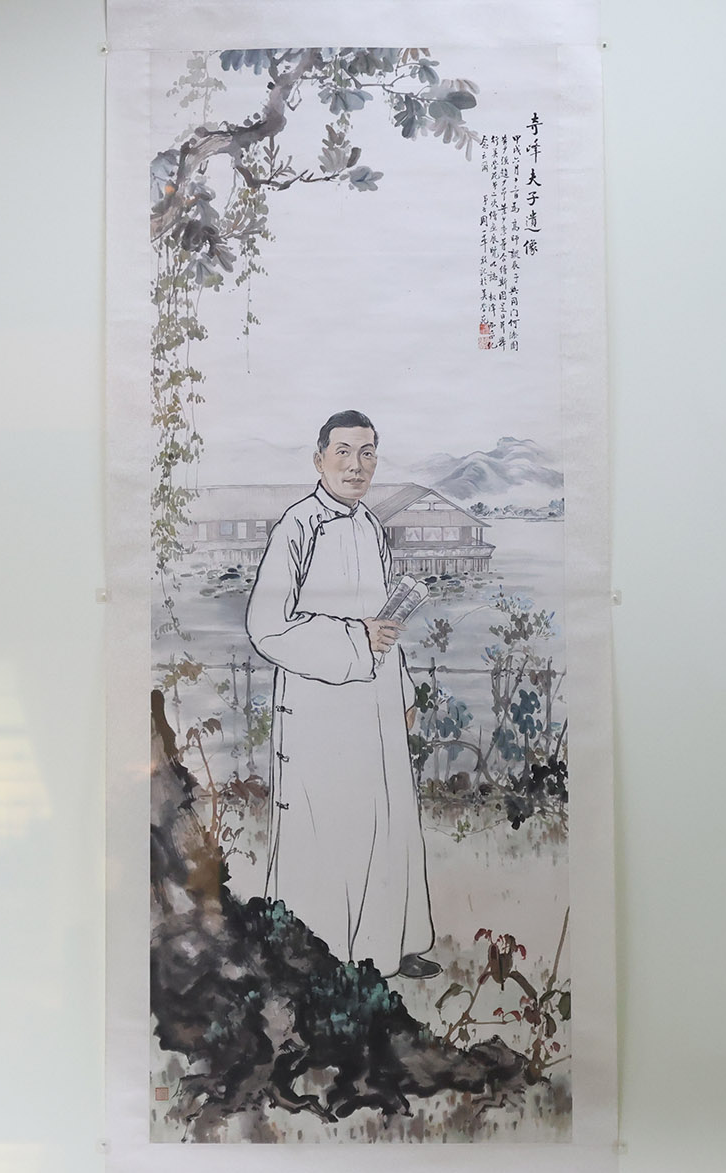

Organized under three thematic displays — “Friendships with his peers in art”, “Artistic journey modeling from nature”, and “Footprints from a life of travel” — the 120 carefully selected, representative works by Chao cover a time span from the 1930s to the 1990s. Many of these were donated to HKHM by the artist, leading to the founding of a gallery in his name at the museum, when it opened in 2000.

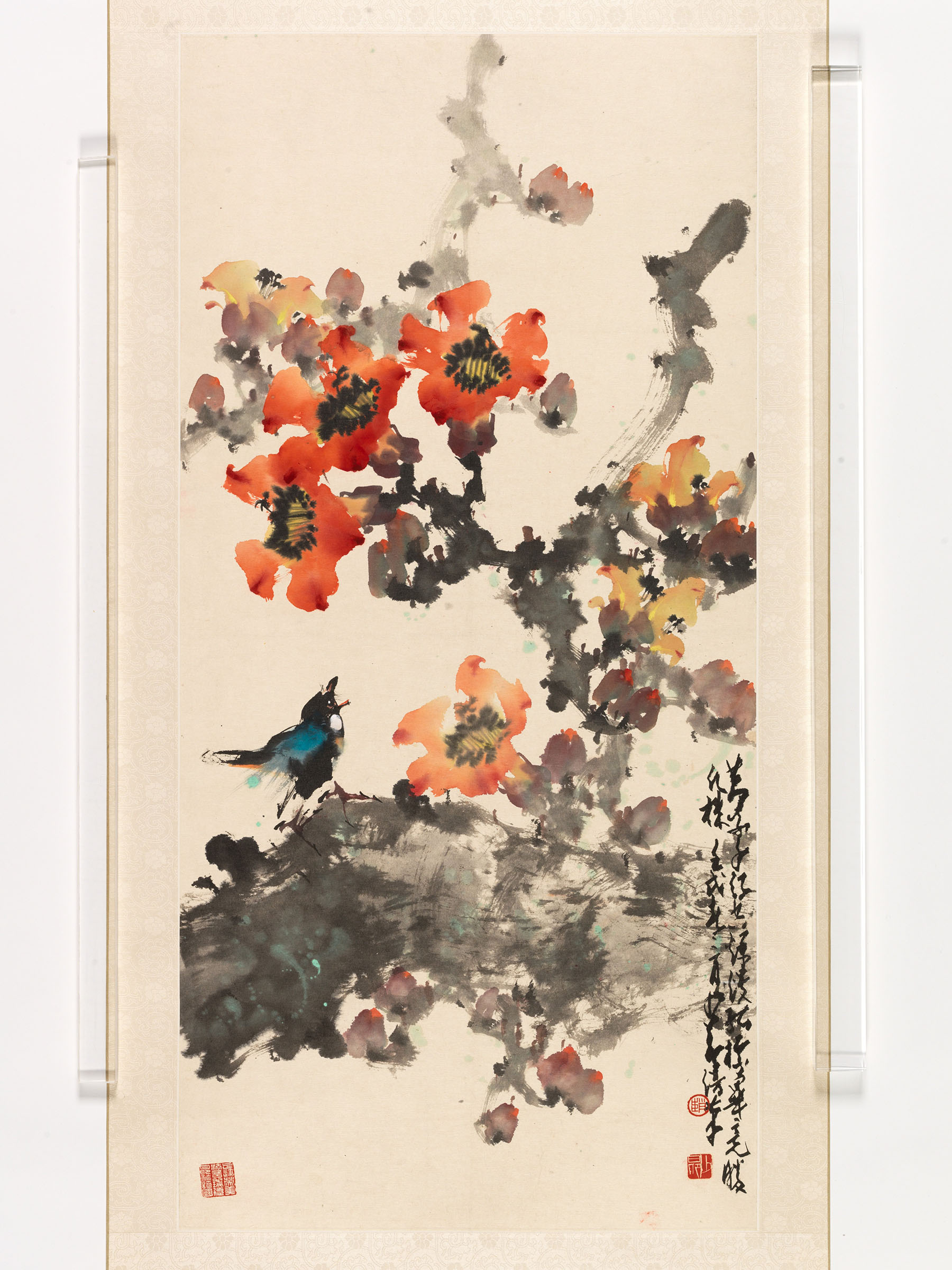

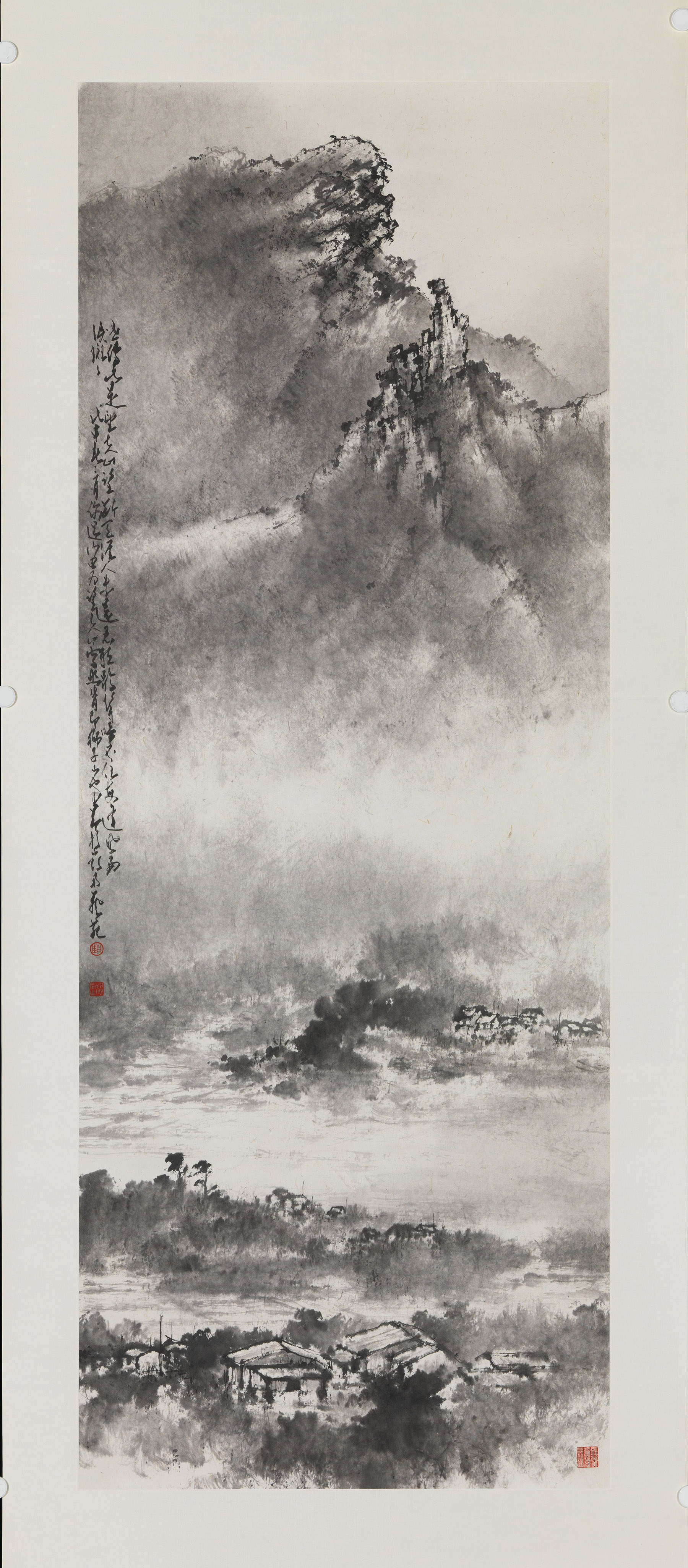

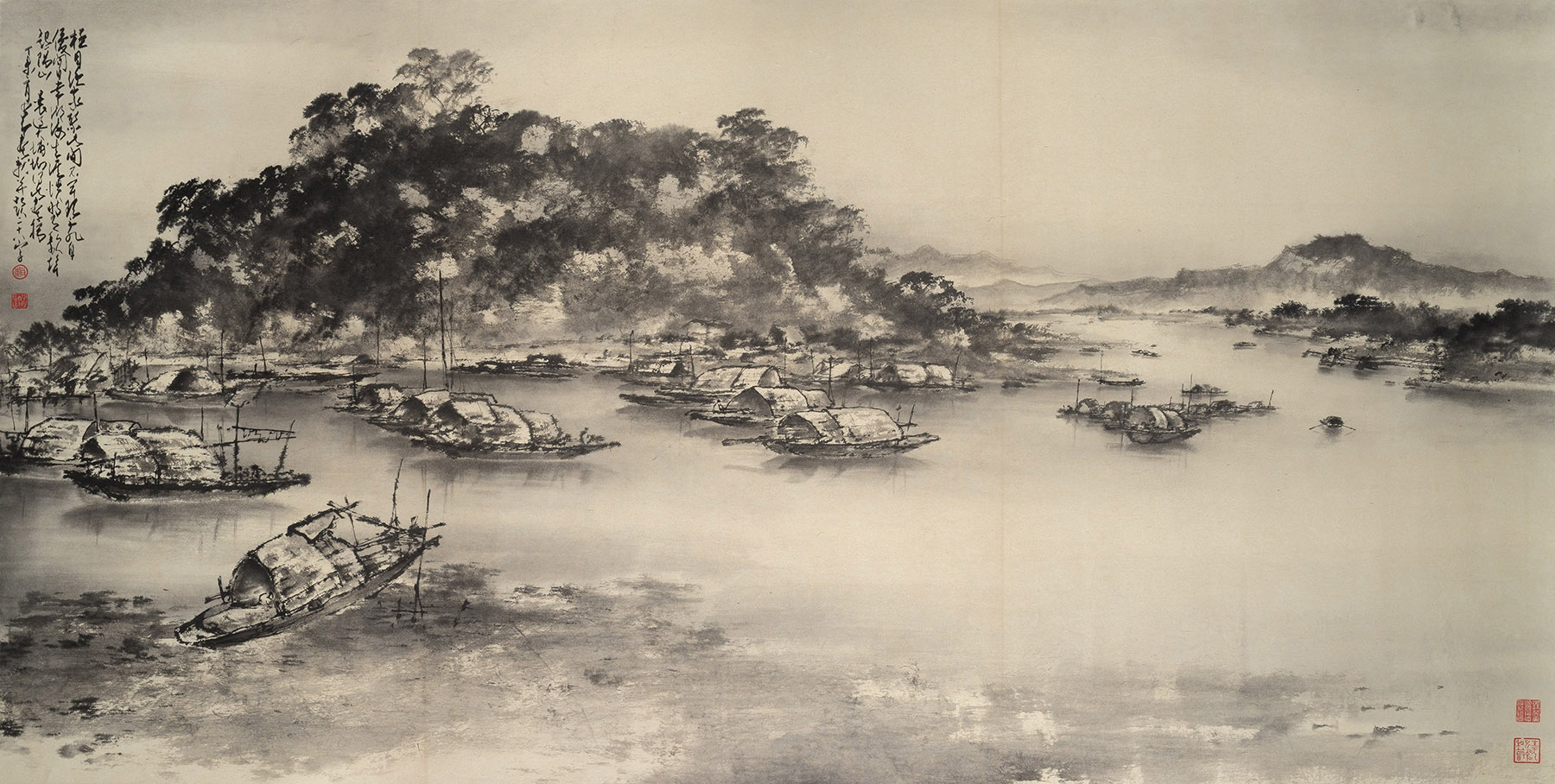

Exhibition highlights include Red Kapok Blossoms (1982), Plantain Trees (1962), River Li in Misty Rain (1943), Ruins (1954), Tai Po Kau, Hong Kong (1967) and Amah Rock, Sha Tin (1968). Another Peacock won Chao an award at the international exposition in Belgium in 1930, following which his works were exhibited in Moscow, Paris and Berlin.

Exhibition curator Lam Yuen-man says that these works highlight Chao’s significant contribution to Hong Kong’s art scene, the Lingnan school of painting, as well as the evolution of Chinese painting in the 20th century.

Xu Beihong (1895-1953), a master of modern Chinese ink painting, considered Chao to be “the top Chinese contemporary painter of flowers and birds”. Lam points out that flowers and birds are recurring motifs in Lingnan-school art, and the ones painted by Chao are “lifelike and full of natural charm”.

“His works are characterized by simple but dynamic strokes and brilliant but elegant colors,” she says.

She adds that Chao’s focus was on closely observing nature in order to come up with accurate portrayals of bird anatomy and features. “In particular, a precise depiction of their eyes and fleeting movements were key to Chao’s expressive interpretation of bird life.”

Red Kapok Blossoms is a fine example of Chao’s use of the mogu technique — applying diffused ink without outlines to represent a flower’s shape, the play of light and shade on it and its texture, managing to do it all with just a few brushstrokes.

Lam points out that Chao’s own works illustrate the artist’s contention that the expertise of drawing a flower petal using a single brushstroke is possible to achieve only after one has acquired a solid foundation in the art of sketching.

Ho adds that Chao had excellent control on wielding the paintbrush, and was highly skilled at realizing the colors and tones with accuracy. “Even when he was making a single stroke with his brush, he could produce a deeper and a lighter tone simultaneously.”

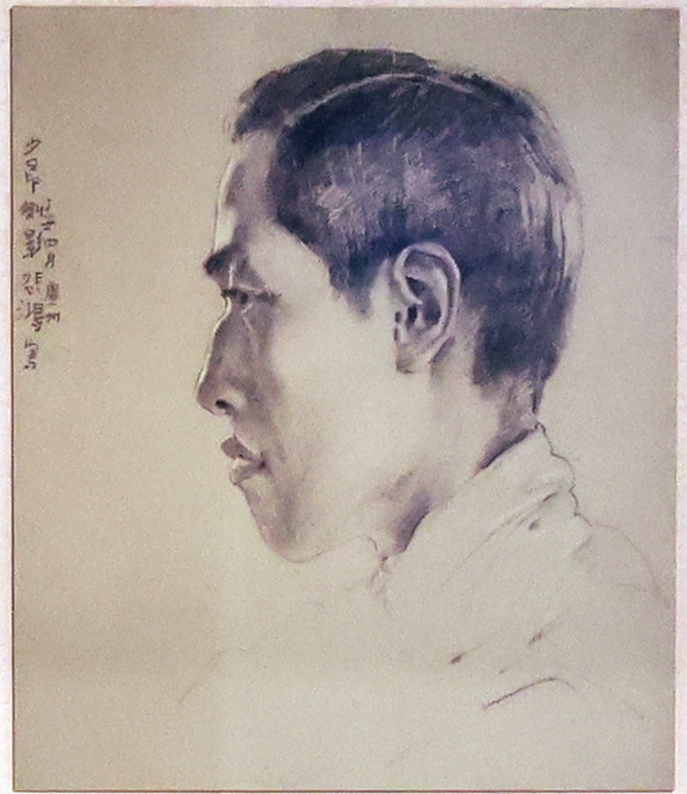

Sketching from life

Chao learned the ropes of Lingnan-style practice from his mentor Gao Qifeng (1889-1933), one of the three founders of the Lingnan school. Chao had joined Gao’s studio in Guangzhou at the age of 16.

Born into a well-heeled family in Panyu district in Guangzhou, Chao had to drop out of school at 11 and start earning a living after his father died. For a while, he worked as a warehouse keeper.

The youngest of the seven well-known disciples of Gao, Chao was considered the best, though his training period had lasted only six months.

Chao once said that Gao’s greatest contribution to his life was “igniting the fire of aesthetics in my heart”. “I had abundant passion for both copying for practice and making new works during my half year at the studio. Mentor Gao’s spirit has been guiding me since then.”

Lam says that Chao devoted himself to upholding the spirit of traditional Chinese painting while incorporating the best of both Eastern and Western art traditions in his work. She adds that the artist placed a special emphasis on sketching from life, which enriched his style.

Chao’s contention was that rather than working within the confines of a studio, a painter of nature should go out into natural surroundings in order to gain insight about it before starting work on a piece. Lam says that Chao himself diligently explored nature in search of inspiration, meticulously studying natural objects in minute details with the aim of making his works realistic while leaving his personal imprint on them.

Promoting Lingnan art

Chao is widely credited for playing a key role in promoting Lingnan-style art.

“He was the only one who has succeeded in taking the legacy of the school forward,” says Ho.

In his lecture titled “Chao Shao-an in the Context of Lingnan Painting”, delivered at HKHM in September, Zhu Wanzhang, a curator at the Hong Kong Palace Museum, described how second generation onwards, the Lingnan school of artists chose either the path of tradition or innovation.

He says that Chao, who belonged to the second generation, “embraced innovation, which resulted in a fresh and natural style that appealed to both refined and popular tastes”.

“He also practiced the literati tradition of Chinese painting, opening a studio in order to pass on his knowledge through teaching.”

The Lingnan Art Studio in Guangzhou opened in 1930. It was relocated to Hong Kong in 1948, after Chao moved his base to the city. For more than 60 years, he taught local and international students at his studio, which shaped up into a hub of nurturing third-generation Lingnan-style painters. It also functioned as a go-to center of Lingnan art in Hong Kong and internationally. Chao also traveled widely, with a mission to introduce Lingnan art to other parts of the world by putting on exhibitions. He had visited Japan and the United States among other countries for that purpose.

Ho, who started art classes under Chao in 1979, recalls an American fellow student visiting Hong Kong on a regular basis in order to learn directly from Chao. After she couldn’t make those frequent visits anymore, the lessons continued by postal correspondence. Ho says that Chao shared his expertise generously with his students, “without holding anything back”. He even shared the techniques involved in making the iconic White Peacock with Ho. It was a proud moment for her when she managed to produce a replica, following the guidance from her teacher.

By celebrating Chao’s works, HKHM is continuing the artist’s mission to enhance the visibility of Lingnan art and make more viewers aware of its significance.

ALSO READ: Burgeoning cultural scene creates an arts oasis

“The exhibition allows people to appreciate the legacy of Lingnan-style painting and the main attributes of a second-generation painter from that school,” Zhu says.

“Visitors can see from Chao’s works how the Lingnan style has developed and evolved in the Lingnan region, particularly in Hong Kong. They can also see the changes in the styles of mainstream painting over time.”

If you go

Legacy of Lingnan School of Painting: In Commemoration of the 120th Anniversary of the Birth of Chao Shao-an

Dates: Through Feb 23

Venue: Hong Kong Heritage Museum, 1 Man Lam Road, Sha Tin

https://hk.heritage.museum/