Researcher recounts decades of safeguarding artifacts, revealing the hidden rhythms of history in a new book on the Palace Museum, Yang Yang reports.

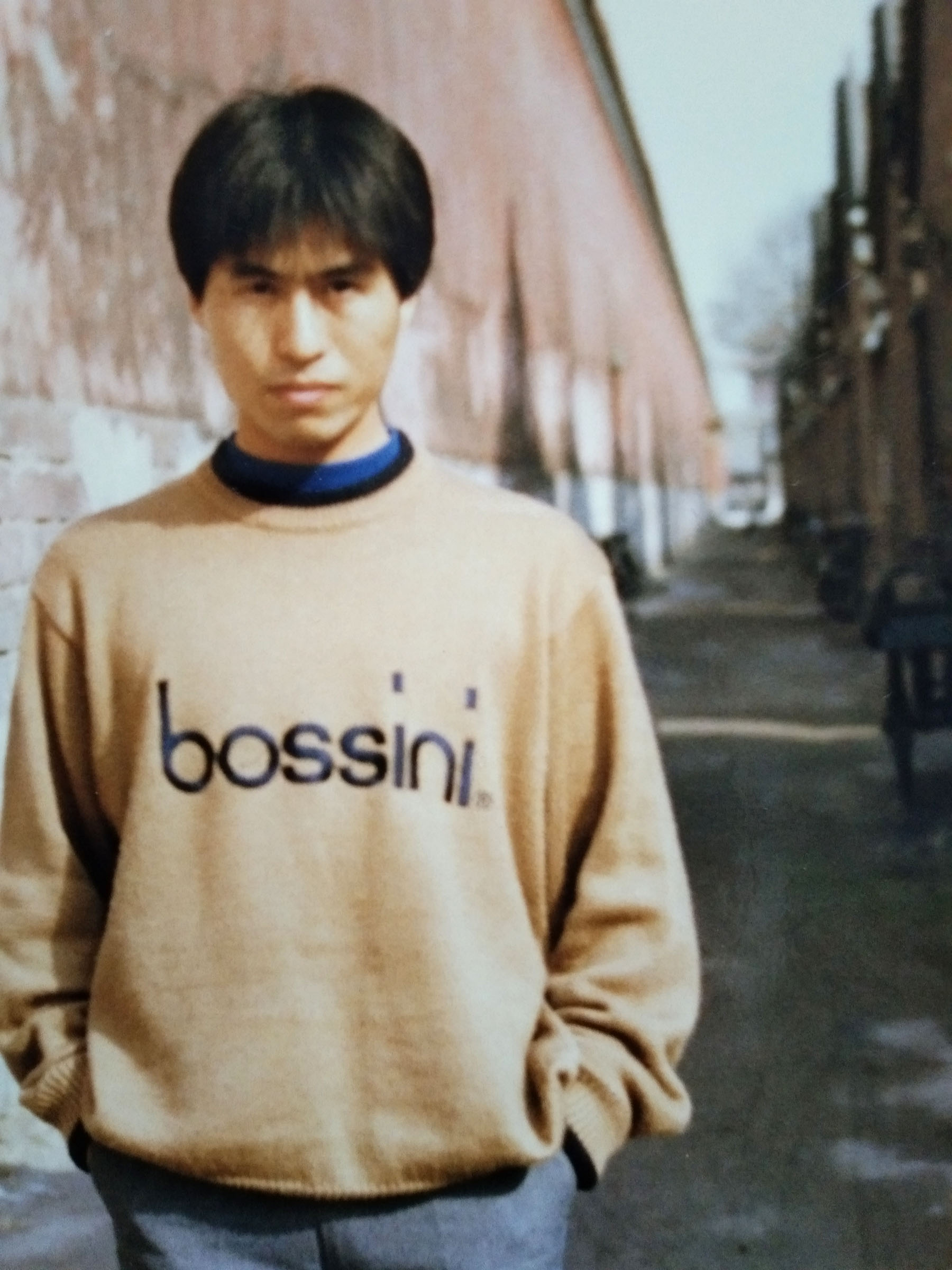

On a drizzling day in September 1985, 20-year-old Wang Zilin came to Beijing's Tian'anmen Square after enrolling in Peking University. On a sudden impulse, he stepped into the Forbidden City. When he walked out of the vermilion palace gates, an idea came to him: "How wonderful it would be ificould work here!"

Four years later, graduating from university majoring in archaeology, Wang found himself captivated once more by the palace complex. Passing a majestic Corner Tower of the Forbidden City on his way to a job interview, he abruptly abandoned his original plan, went straight to the museum's personnel department, and applied to work there. From that moment, his lifelong career with the Palace Museum began.

In 1998, Wang was transferred to the religious group, responsible for managing over 60 original state palace storerooms. These spaces are scattered throughout the Forbidden City: from the "three great halls" to the "three rear palaces", from the Buddhist Hall (Fo Tang) in the Celestial Loft (Xian Lou) of the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin Dian) to the Eastern Warm Pavilion (Dong Nuan Ge) of the Pavilion of Nurturing Harmony (Yihe Xuan). Inside were thousands of artifacts: some long forgotten beneath layers of dust, others — bronze tripods and vats — left outdoors to weather the elements.

READ MORE: Hidden behind the halls of royalty

"The artifacts in the original palace settings are diverse and wide-ranging. They are, in essence, time capsules that record past life scenes and the preferences and pursuits of ancient people. The original palaces are like a vast ocean — unfathomable, where treasures lie hidden, and everything is covered," says Wang, now the director of the Research Department of the Palace Museum. His study focuses on imperial architecture and original palace furnishings of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

In addition to religious statues, thangkas, and ritual implements, there are also paintings and calligraphy, wall hangings, furniture, bronze, jade, porcelain, enamel, gold and silver items, textiles, musical instruments, swords and clocks. Collectively, they form one of the richest archives for the study of court history, material culture, and the evolution of interior decoration in China.

The task was daunting. More than 60 storerooms had to be managed by only four staff members. From 2004 to 2010, Wang and his colleagues painstakingly tackled this "hard bone" — a long, painstaking process of inventory. They dusted the artifacts in over 60 original state palaces, verified them one by one, and kept digital records. Every piece, whether large or small, received the same meticulous attention.

Some storerooms were actually in dangerous disrepair, with fragile staircases, and some artifacts were stored in cramped, unlit spaces. Others were placed on top of tall cabinets, altars, or inside towers. Handling fragile treasures in such precarious settings demanded not only patience but also courage as a single misstep could mean falling from dark staircases, altar tops, or makeshift scaffolding.

"Although danger constantly lurked around us, it didn't scare us. Instead, it trained us and strengthened our resolve," says Wang.

For seven years, Wang and his colleagues moved ceaselessly through storerooms of all sizes, weaving among artifacts piled high and hidden in shadows.

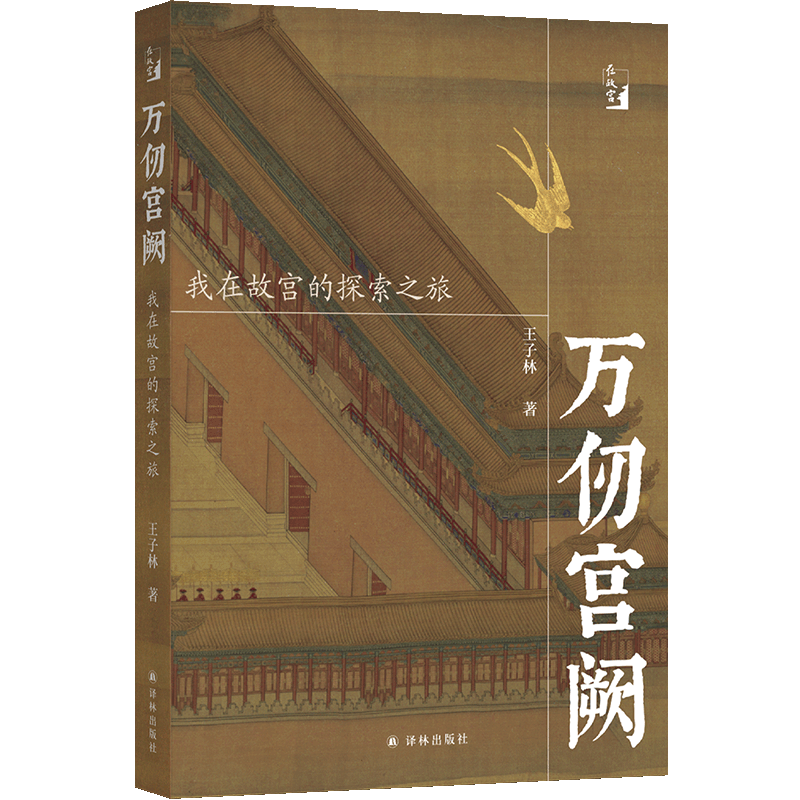

In his new book Wanren Gongque: Wo Zai Gugong De Tansuo Zhilyu (literally, Towering-walled Palace: My Exploration Journey in the Forbidden City), which Yilin Press has recently published, Wang meticulously recounts these experiences. With warmth and detail, he describes the daily work of the Palace Museum employees: cataloging relics, safeguarding storerooms and planning exhibitions.

The book weaves personal experiences with academic reflections, using a warm and delicate narrative to portray the author's nearly 40-year journey working at the Palace Museum.

Through a deep analysis of the architecture, collections and historical culture of the Palace Museum, the book explores the intertwining of tradition and modernity, contemplating how to innovate while preserving cultural roots.

"With over 30 years of dedicated research into the original state of the palaces, the author's unique experiences infuse academic investigation with warmth, reflecting his deep reverence and passion for cultural heritage," says Wang Lei, the book's editor.

"From his firsthand perspective, Wang Zilin guides readers into the Forbidden City's most secret corners — the unrestored palaces that remain largely untouched since imperial times. Amid the weathered palace walls and dust-covered artifacts, he unveils the cultural codes of the Yuan (1271-1368), Ming, and Qing dynasties' orthodox heritage," the editor says.

When connecting one palace to another, Wang Zilin finds that a field of ancient culture emerges.

"The Zhou Li (Rites of Zhou), Li Ji (Book of Rites), Shi Jing (Book of Songs), and Shang Shu (Book of Documents) are its original narrative codes, the foundational principles. These are the codes hidden within the original palaces and the light within ancient culture," the writer says.

But he also warns that many original palace spaces have "disappeared "over time through renovations.

According to Wang Zilin's rough estimate, only two truly original spaces are left: the Xuanji Hall Complex and the Yanqing Hall-Huifeng Pavilion area. The ground remains as it was in the past, the buildings are the same as before, and the flowers, grass and trees are also from the past. Even the piece of wall plaster that is about to fall off is from the past.

"Can we preserve these two original spaces?" Wang Zilin asks.

Unlike other museums, the Forbidden City is not only a repository for collection, preservation, display, research and education, but it also has an emotional and nostalgic role because it is a World Heritage site, Wang Zilin writes.

He draws comparisons to the Parthenon atop the Acropolis in Athens. Despite its broken columns and scattered remnants, the ruined temple retains its grandeur. Its very imperfections testify to history and endurance.

"So, must a weathered door be replaced with a new one? Must a crumbling wall be torn down and rebuilt as a new wall? Should a seemingly peeling column be removed and replaced with a new wooden one? These are questions worth pondering," he writes, advocating instead for the philosophy of "restoring the old as old".

ALSO READ: Inking inspiration from classical gardens

This concept has also influenced subsequent preservation practices at the Forbidden City.

"In recent years, we have gradually recognized the importance of 'restoring the old as old'. For example, we reglaze and refire removed glazed tiles, preserve some paintings in their original state without repainting, and retain original materials whenever replacement is not absolutely necessary. We oppose turning the Forbidden City into a park or garden; as a World Heritage site, its architecture and environment must remain tied to the past," Wang Zilin says.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn