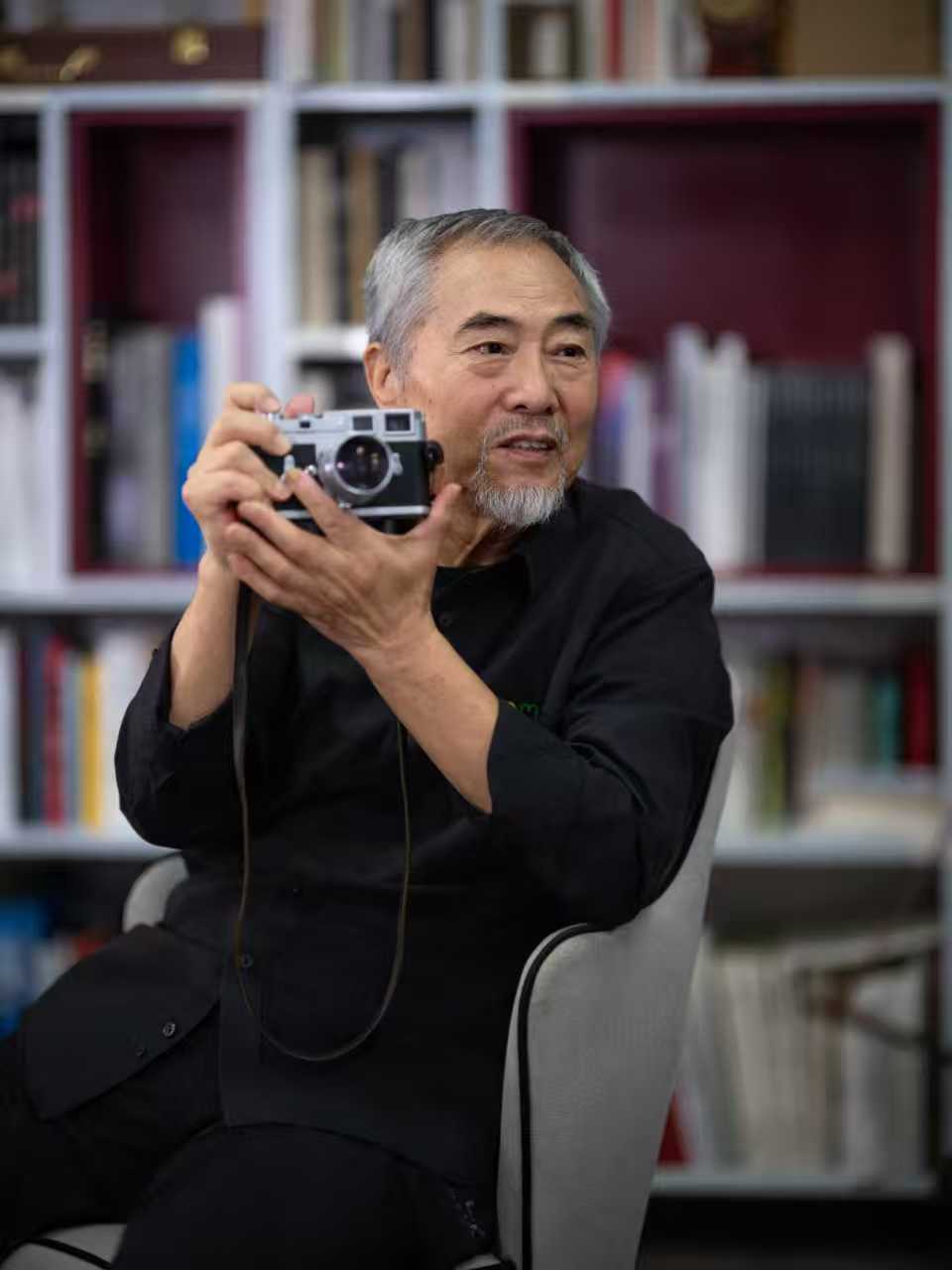

For documentary photographer Hu Wugong people are the essence of photography

When Hu Wugong picked up a borrowed camera in 1967, he didn't gaze upon grand landscapes or revolutionary scenes. Instead, he turned inward — to the small world of his parents and sister. These early photographs, simple and heartwarming, contained the seeds of a philosophy that would shape his life: the essence of photography lies in people.

In the 1980s, as China entered an era of reform and opening-up, Hu immersed himself in the villages and towns of his native Shaanxi province. His lens captured festivals shrouded in incense, funerals woven with sorrow and ritual, and weddings where stubborn traditions collided with modern ambitions. "I don't study folklore," he once said. "I study the cultural psychology of specific groups as reflected in folklore."

This subtle distinction marks him as more than just a recordkeeper of folklore. His work is never nostalgic, nor is it simply a record of fading customs. Rather, it is a critical realism — an attempt to understand how history and change are imprinted on the faces and rituals of ordinary people. In the mid-1980s, Hu found like-minded individuals in a loose group of Shaanxi photographers — including Hou Dengke, Li Shaotong, Shi Baoxiu, Pan Ke, Jiao Jingquan, Qiu Xiaoming and Li Shengli. Collectively, they became known as the "Shaanxi School", a movement of image-makers that rejected fabrication and affectation, embracing reality itself as a profound source of metaphor.

Their credo was simple: oppose falsehood, reject manipulation and focus on human nature. The group later became influential, though critics accused them of being conservative and overly clinging to documentary photography orthodoxy. Hu retorted, "Just because we don't engage in contemporary art doesn't mean we're conservative. Our weaknesses lie in our aesthetic and philosophical foundations, not our convictions."

For Hu, the challenge remains how to maintain the relevance of photography amid shifting aesthetics and contemporary technological change. Recently, when asked about the advent of new technology, he didn't dismiss it. "The emergence of technology such as smartphones and artificial intelligence is humanity's most dazzling epoch-making achievement in the 21st century," he said. "They are more than just a technology or a tool; AI, in particular, has the potential to develop into a species, propelling the Earth into a post-human era."

However, he insists that AI cannot replace the witness of the camera. "From a temporal perspective, AI resurrects history, while photography solidifies reality. At least for now, the two are not interchangeable. Therefore, time and temporality are the dividing line between AI imaging and traditional photography." He adds that the real danger is that AI could make photographers "lazy or timid, afraid to show their face, reduced to beggars who plagiarize others' work".

For Hu, the antidote lies in self-discipline. "Facing the challenge of AI, the only strategy is to train the photographer's own eye," he says. "The essence of photography is recording. Documentary photography can bear witness to both history and oneself. Facing life directly, putting people first, and revealing human nature — this is the true path."

If the reforms of the 1980s shaped Hu's early aesthetic, they also propelled Chinese documentary photography onto a broader stage. He recalls the 1988 exhibition A Difficult Journey at the National Art Museum of China as a watershed moment. "The rise of documentary photography is essentially a revival of realism, thanks to reform and opening-up and the emancipation of thought," he said. "Photographers have extended their lenses to encompass the vast and profound sea of humanity, society and nature, using the joys, sorrows, anger and happiness of countless individuals to showcase the rich emotions of humanity and the social landscape."

However, Hu admits that some gaps still exist. "Because documentary photography in China started later than in Europe and the United States, there is still a significant gap in theory, practice and professionalism," he said. "The discourse on photography is not on China's side, and many excellent works have not yet been widely disseminated. Chinese documentary photography still needs to work hard to have a broad global influence."

He believes that this effort requires more profound thinking rather than technical expertise. "The key to the development of documentary photography in China lies not in technology, but in liberating thought, shifting perspectives and breaking down the stigmas surrounding photography and culture," he noted. "Photographers must possess independent thought and humanistic artistic concepts, facing reality head-on without evasion or shrinking back."

ALSO READ: 150 years of Northwest China imagery in Ningxia photo show

Although Hu has many titles in academic and photographic circles, he simply refers to himself as a photographer. His work consistently examines and captures life through independent reflection. Only when art is imbued with a thoughtful quality can it be imbued with soul.

Over 70 years old, Hu still captures life with an uneasy seriousness. His photographs — funerals in dusty courtyards, workers resting beneath neon lights, elderly men gazing at the ruins of ancient shrines — are not nostalgia but expressions of continuity. They remind us that history, no matter how swiftly it passes, leaves its mark. In an age where images can be transformed through code, Hu maintains a stubborn and irreplaceable presence, insisting on turning his lens on life itself and pressing the shutter.

Huo Yan in Xi'an, Shaanxi province, contributed to this story.

Contact the writers at liyang@chinadaily.com.cn