The great literati of ancient times have left an indelible mark on the growth and dissemination of Chinese culture through music. As Luo Weiteng reports, cultural luminaries of the qin, or seven-stringed Chinese zither, have gone to great lengths to preserve the qin legacy, threading its diverse lineages into the vibrant cultural tapestry of Hong Kong.

Over a millennium ago, Liu Yuxi — a great poet of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) — penned his meditation that has echoed through the ages, “The swallows that once graced the mansions of the elite have now found their nests among common households.”

His thoughts have captured more than a passing change in fortune, tracing the quiet migration of high culture to touch broader lives.

Once an art form associated with the elite class of scholar-officials of imperial China, the qin — a seven-stringed plucked instrument that has been played in China for over 3,000 years — has found resonance beyond the walls of lineage and learning.

From the turbulence of the last century, shaped by history and geography, Hong Kong has made itself a unique habitat for the qin, or guqin, as the Chinese zither is commonly known today.

READ MORE: HK guqin maker's timeless creation of millennial instrument

Choi Chang-sau (1933-2025) — a renowned Hong Kong qin maker — vividly recalled a fateful encounter with the millennium-old instrument in an unpublished interview he gave me in 2013.

It all started in the 1950s when a gentleman, Xu Wenjing (1895-1975), stepped into Choi’s family-run musical instruments shop. Xu, a native of Zhejiang province, traveled to Hong Kong to seek treatment for an eye ailment and brought with him several qin worn out through age and time.

The shop produced most of the traditional Chinese instruments used locally, and exported guitars and ukuleles, but none of the craftsmen truly understood the delicate intricacies of the qin. All were suitably impressed as Xu gave precise technical instructions for the instrument to be repaired.

Choi’s father didn’t intend to hand over the family business to his son. Yet, from the moment the young Choi took a glimpse of the world through the qin, he was hooked. The fleeting encounter became his lifelong motto — “I had never once thought of walking away from the artisanry,” Choi said in 2013. Years later, he took charge of the shop, turning it into an entirely qin affair.

Out of sheer determination, the young Choi often skipped school to seek a single voice of wisdom. Serving tea and running errands, he became a devoted attendant and loyal listener to his newfound mentor Xu, whose eyesight was fading even as his desire to pass down the skills stayed strong. After years of careful observations and tests, Xu eventually took on Choi as a disciple.

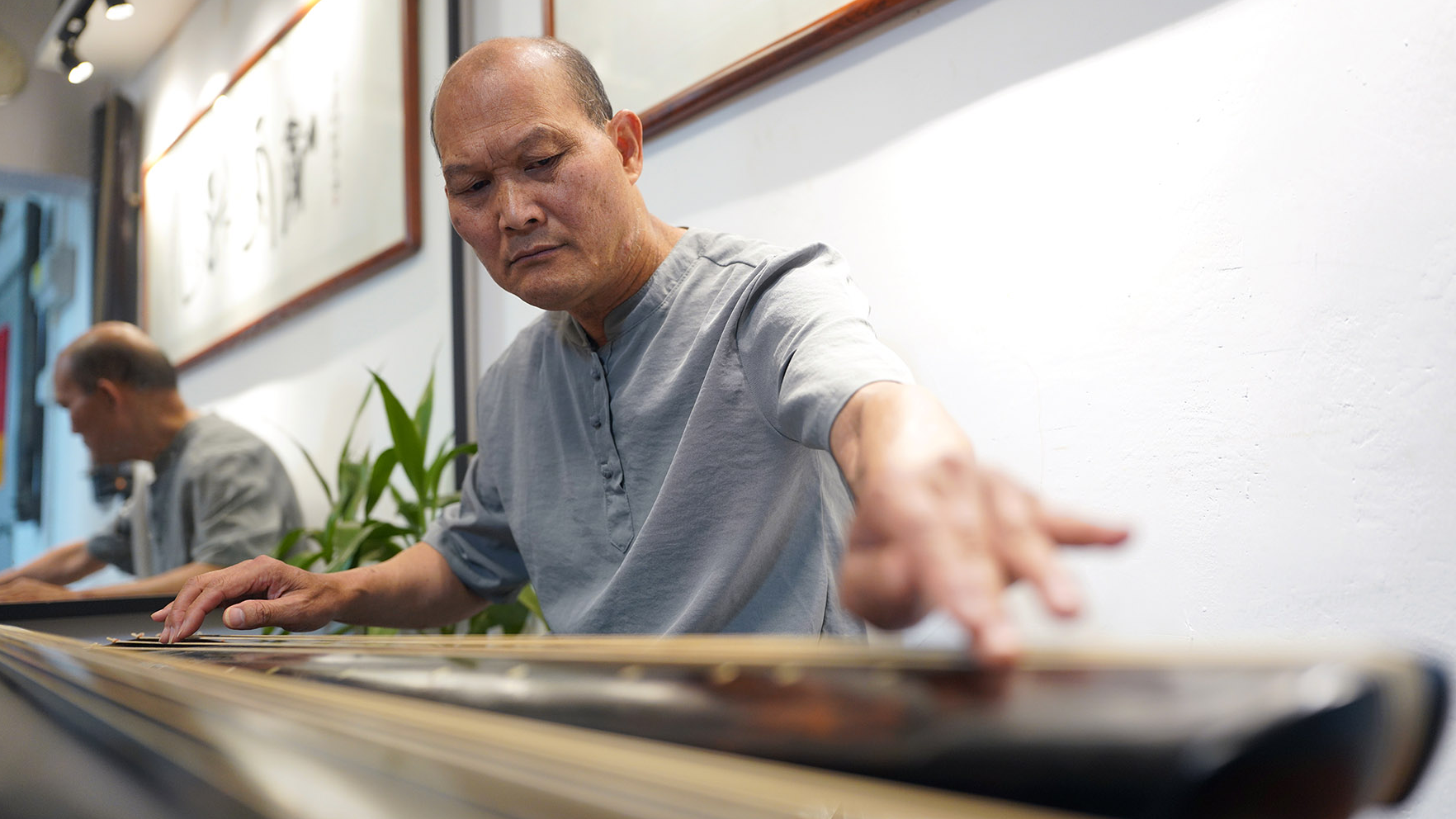

As Xu gradually lost his sight, it was through his hands that the qin’s ancient secrets were passed on. In the quiet dialogue between silk and wood, which made up the strings and body of the qin, lies one of the craft’s most profound truths — the art of touch. Through the time-honored practice of oral teaching and hands-on demonstrations that inspire true understanding, Choi learned to trace the qin’s gentle curves with his fingers and tap its wooden body to listen for subtle shifts in tone.

Known for his attainments in qin performance, the interpretation of ancient scores, and the art of crafting the instrument itself, Xu had acquired the skill through a long line of masters of the Zhe school (named after the region of Zhejiang). This distinguished lineage originated during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) and has taken root in Hong Kong since Choi assumed Xu’s legacy.

Lifelong devotion

Zhuoqin, or the construction of the qin, is a refined handicraft. Starting with the selection of appropriate pieces of wood, it involves a series of steps of work, including chopping, hollowing, fitting, assembling, cement priming, sanding, lacquering and stringing until it reaches the final stage of an instrument.

During those years, Choi helped Xu make three qin despite failed attempts. He made the fourth bid under the master’s instructions, signifying his casting off the apprenticeship shell. After Xu’s passing, Choi became Hong Kong’s sole specialist in the delicate craft of making and repairing qin. His devotion earned him the friendship of the city’s cultural luminaries, such as celebrated Chinese scholar Jao Tsung-i (1917-2018) and the master of Lingnan school painting, Chao Shao-an (1905-98), whom Choi described as “those who truly understand the qin”. “They understand me.”

As the instrument is most expressive of the essence of Chinese aesthetics, the qin has helped shape Choi, teaching him “patience, sincerity and simplicity”. Perhaps, these very virtues became his anchor when storms struck — the mass production of machine-made qin flooding the Chinese mainland market and the devastating illness that forced him to consider retiring. He found himself asking, “What can I do if I can no longer make qin?”

In 1993, he turned the store into a qin workshop dedicated to passing the art of making qin to amateur players and keeping the exceptional thread of heritage alive on Hong Kong soil. His students came from diverse walks of life and age groups, reminiscent of “swallows from noble halls” now seen in more varied corners of society. In 2011, the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society came into being.

Calling himself a “qin-making fanatic”, Kelwin Kwan, the society’s vice-president and instructor, fell under the seven strings’ spell through a chance encounter with Choi’s once-in-a-lifetime solo qin exhibition in Central decades ago. “I stood there in awe for an entire afternoon, and left with his name card, treasured in my wallet like a quiet promise,” Kwan recalls. “Years later, when I returned to Hong Kong for good, my first act was to make a handwritten plea for apprenticeship.”

“Master Choi crafts the qin out of a love too deep for words. Beyond all the meanings and grand narratives of artistic legacy, cultural continuity and the weight of tradition, to him, it is simply what must be done,” says Wee Lian Hee, a council member and instructor of the CCS Qin Making Society. The Singapore-born professor of linguistics at Hong Kong Baptist University was enthralled to hear the extraordinary notes of qin from some old recordings in high school, when its very existence was almost unknown in the Lion City and other places abroad. The seeds of a lifelong devotion were quietly sown and, in time, took root during his journey to Hong Kong.

Enduring tradition

Among the first batch of Choi’s students, Yung Hak-chi carries on a family lineage of qin studies passed down through six generations spanning nearly two centuries. The succession of qin studies in the Yung family offers another lyrical glimpse into the tradition’s enduring resonance in Hong Kong.

Yung still reminisces about the calligraphy hanging on the wall of Choi’s workshop, “To do a good job, one must first sharpen one’s tools.” He made three qin from scratch within two years under Choi’s guidance.

Studying under Choi, woodworking skills aren’t required, but the ability to draw sound from the instrument and grasp its soul is a prerequisite — the overarching rule Choi inherited from Xu. The essence of the craftsmanship, Choi often said, lies not in shaping wood, but in understanding the music within.

For Yung, playing the qin has been an integral part of home education since childhood. All his family members have been exposed to qin studies from an early age through hands-on demonstrations. Such a traditional way of teaching — much like how Xu had taught Choi in making qin — involves the teacher first playing a verse several times, during which the student listens attentively while remembering the fingerings, the rhythm and the hui (marker) positions by heart before trying to simulate.

“Over time, playing has become second nature,” says Yung.

As the Yung family made its mark on the local qin community with unique fingerings, their legacy has been enriched by a treasured collection of qin scores.

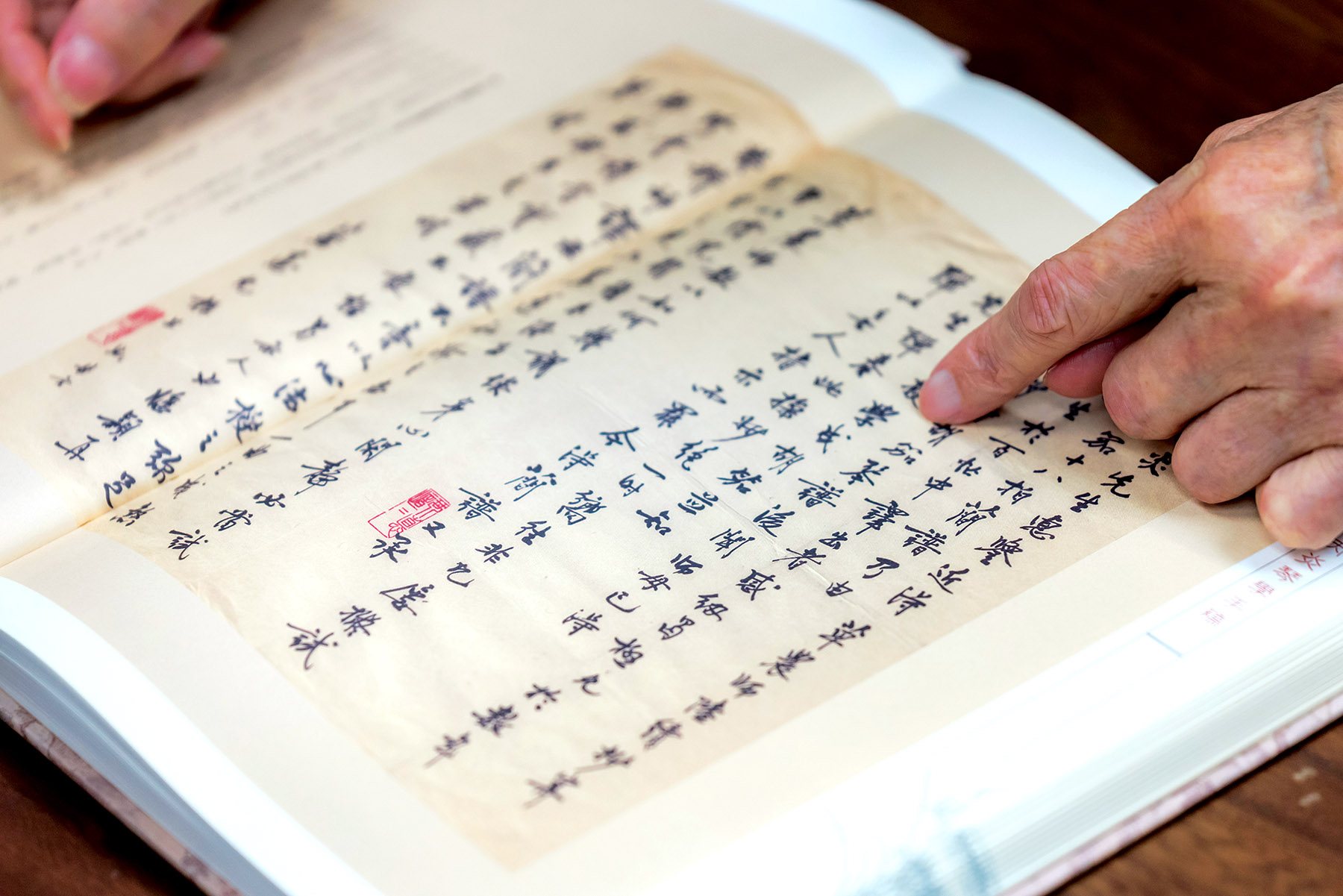

For generations, in their pursuit of musical purity, qin practitioners have held scores in high esteem and seldom revealed them to others. Yung’s strong family links to the qin trace back to their ancestor, Qing Rui, who had traveled across Guangdong in the service of the state during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and gathered rare scores of the qin and the se (another traditional Chinese plucked-string instrument), making them into a handbook.

Anxious that the Japanese army would view the tablature as encoded messages after invading Guangzhou in 1938, the Yungs destroyed the handbook’s original printing blocks, except the one and only copy handed down in the family.

In 1951, the Yungs relocated to Hong Kong, among the earliest qin musicians who settled in the city. Yung recalls his father enshrining the heirloom qin manuscripts at home, echoing their forebears in Guangzhou who offered incense at dawn and dusk. His family’s rich musical legacy remained hidden from Hong Kong’s qin community until Chinese music scholar Tong Kin-woon visited in 1972 and humbly requested access to the Yungs’ long-guarded scores for compiling a book.

In the 1990s, Yung began teaching, and the once-private lineage quietly moved beyond its ancestral bounds. Office workers, drivers, retirees and homemakers — those living ordinary lives — came to Yung, seeking a measure of stillness amid the hustle and bustle of a city that never sleeps. Yung also devoted years to restoring and cataloguing his family’s centuries-old scores, collaborating on publications that give melodies once confined to private halls resonance and reach among a broader audience.

Shared dedication

Indeed, qin scores are the reason that Yao Gongbai traveled all the way south to Hong Kong. The qin master saw the bustling city as a place for a pure mind to sort out the works of his late father, Yao Bingyan (1921-83) — one of the most eminent contemporary experts known for his brilliant reconstitutions of qin pieces that were disappearing from the orally transmitted repertory.

The notations of qin music are in the form of tablature that only indicates the fingerings, with no direct record of pitch, specific rhythm or note values. The strength of the right-hand plucking and the speed of the left-hand movement are not indicated either. These factors lead to versatile rhythms and fingerings in qin playing and the flourishing diversity of qin schools.

Such a notation system (known as jianzipu), solely designed for the qin and only readable to qin players, is a combination of written Chinese characters and numbers. It was once described as “the book from heaven” in Honglou Meng (Dream of the Red Chamber) — the classic Chinese novel from the Qing Dynasty, demonstrating the esoteric nature of the system.

Through the ages, many surviving old qin scores are no longer played. Their tablatures and fingering may differ from those of more recent versions, and the rhythmic elements are not notated. To make the scores playable, from a detailed study and recreation of the rhythm, there’s a special procedure called dapu.

Throughout his life, Yao Bingyan revived nearly 50 melodies for contemporary audiences, pioneering modern interpretations of ancient qin masterpieces such as Jiu Kuang (A Feigned Drunkard) and Guangling San (The Guangling Suite).

In Hong Kong, Yao Gongbai put the finishing touches to three publications of his father’s manuscript scores, essays, correspondence and writings from close associates. He regards the undertaking as a “shared dedication of two generations from the Yao lineage of the Zhe school of playing” and “a meaningful tribute to the qin legacy”.

As the once quiet, niche artistry became absorbed into Hong Kong’s culture following its recognition by UNESCO as a world heritage treasure, Yao Gongbai accepted an invitation from the Cultural Department of Hong Kong Chi Lin Nunnery to be a researcher in 2009 and moved to the city.

His arrival, seemingly a stroke of serendipity, enriches the mosaic of locally cultivated qin culture. Yet to Yao Gongbai, who was born in Hangzhou and raised in Shanghai, the move ran on the wheels of inevitability — his ties to Hong Kong were rooted in the spiritual kinship shared with the older generation of Chinese literati.

It all stretched back to the late 1930s when Tsar Teh-yun (1905-2007) — a mentor to generations of Hong Kong’s fine players and scholars — set foot on the territory. There, she met Zhejiang-born qin master, Shen Caonong (1891-1973), and embarked on her qin odyssey.

When Hong Kong was occupied by Japanese forces, they returned to Shanghai. During those turbulent days, Shen, who forged a lifelong, father-son-like bond with Yao Bingyan, led Tsar to study under the luminaries of diverse qin traditions, weaving her into the fabric of China’s sonic heritage.

“As Madam Tsar’s one and only mentor, Master Shen held no sectarian bias, never treating disciples as personal possessions. His liberating vision aimed to broaden their horizons — a philosophy echoed by my father and elder masters,” says Yao Gongbai, who inherited the skills and techniques from his father, yet holds equal reverence for elder masters like Wu Zhengping (1907-79) and Zhang Ziqian (1899-1991), whose generous teachings have been a guiding light in his musical journey.

“Qin artistry thrives on expansive exposure and open exchange. Only by bridging friendships through shared melodies can one cultivate true artistic depth and personal refinement. Otherwise, the path would narrow into insular stagnation,” says Yao Gongbai.

After peace was restored, Tsar returned to Hong Kong in 1950 and devoted herself to passing on the art of the qin amid the city’s concrete sprawl. The current she set in motion still flows. Yao Gongbai stands in that stream today. The master artisan sees the quiet weight of responsibility to “magnify qin’s light in Hong Kong without fences of lineage or exclusivity”.

The vision draws a raft of students from across the country for his unreserved transmission of art, becoming part of the living legend of silk and wood — whispered from hand to hand, note to note.

The millennial flight of Liu Yuxi’s swallows has threaded through dynastic winds and shifting tides of fortune, tracing the arc of history with silent wings. “Through flames of war, sweeping upheavals and waves of foreign invasion, the qin has carried its enduring melodies and gently extended its reach, like currents flowing deep without end,” says Yung.

ALSO READ: Instrument at the heart of heritage

At critical historic junctures, important transmission lineages found their way into Hong Kong and flourished, anchoring the city in the quiet resilience of cultural continuity.

Yao Gongbai affirms the strength of the people.

“The qin lives on — ever evolving as it is passed down, ever passed down as it evolves. Born of the people and rooted in folk tradition, it draws strength from a deep cultural heritage and a broad popular embrace. That’s why it has never fallen silent and why its music will flow on.”

Contact the writer at sophialuo@chinadailyhk.com