A new show at M+ museum looks back on how art and artistic sensibilities evolved in Guangdong and Hong Kong over the first eight decades of the 20th century. Chitralekha Basu reports.

Opened at M+ museum on Saturday, Canton Modern: Art and Visual Culture, 1900s-1970s tells the vast, layered and complex story of the art that emerged from the southern Chinese port cities of Guangzhou (formerly known in the West as Canton) and Hong Kong over eight decades that saw regime changes, wars, famine and the “cultural revolution” (1966-76).

“The art of this period was created against a very tumultuous historical backdrop,” says Tina Pang, M+’s curator of Hong Kong visual culture, who co-curated the show with the museum’s associate curator Alan Yeung. She adds that the show aims to take viewers back to a time when the trend of proliferation of images in society was beginning to emerge.

READ MORE: Tale of three cities

“Our exhibition looks at the visual culture of this period, including pictorials, and also paintings in many different mediums — ink, primarily, but also oil painting, prints and photography,” she says. “We wanted to foreground how the artists wanted to depict the world that they were seeing and experiencing, how they wanted that reflected in their work, and also how they wanted those images to be distributed in the world.”

For this reviewer, two pieces from among the over 200 artworks on show represent the yin and yang of what artists made of the reality around them — a theme that Pang says “motivates the entire show”.

The first is a 97-centimeter-by-181-cm woodblock print of a panoramic landscape from 1975, done in hyperreal green, red and earth tones. It shows mining activity at the oil fields in Daqing, Heilongjiang province, as a red flag-wielding army marches across the frame.

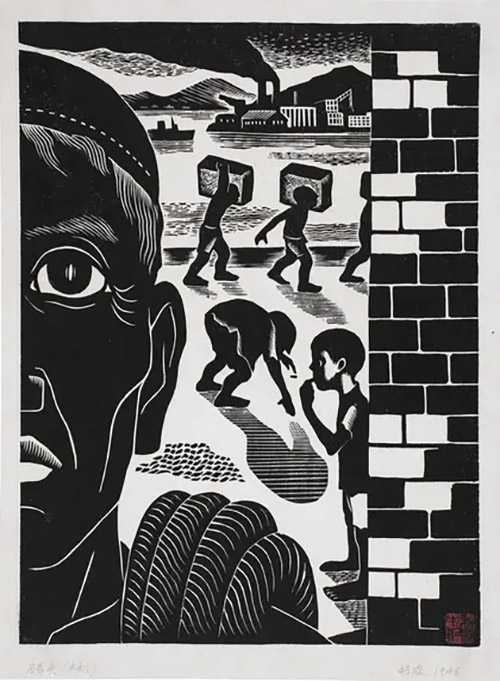

The second, a much smaller woodcut print realized in black and white, is dominated by a close-cropped left-half of a weather-beaten face, with an over-the-shoulder view of a Hong Kong dock in the background. This image — Ship Terminal by Huang Xinbo (1916-80) — could have been referencing a 0.5 selfie, if it were not made in 1946. However, the motivations behind creating these prints and the universal and obsessive impulse to record and disseminate one’s everyday experiences in the form of images posted online that we see today are fundamentally similar. Though from different times, both prints were made with the idea of mass circulation.

“Printmaking is one way for images to circulate in society because prints can be reproduced as well as photographed, and also circulated via pictorial publications,” says co-curator Yeung.

Called Transfer Fighting to the New Oilfield, the 1975 landscape by Li Hua (1907-94) and Liang Dong (1926-2014) was created with the idea of circulating the image of a prosperous, industrialized China, self-sufficient in its oil reserves.

Yeung says that the discovery of the oilfield in Daqing in 1959 had “turned this site into a symbol for China’s scientific progress during the Cold War period (1947-91)”. He adds that while the depiction of the scene is faithful to the real-life situation, the use of unrealistically bright and vivid colors “projects a very utopian, optimistic vision of the country”.

“Also it definitely shows a collectivity, basically a mobilization of many people toward the same goal of building China.”

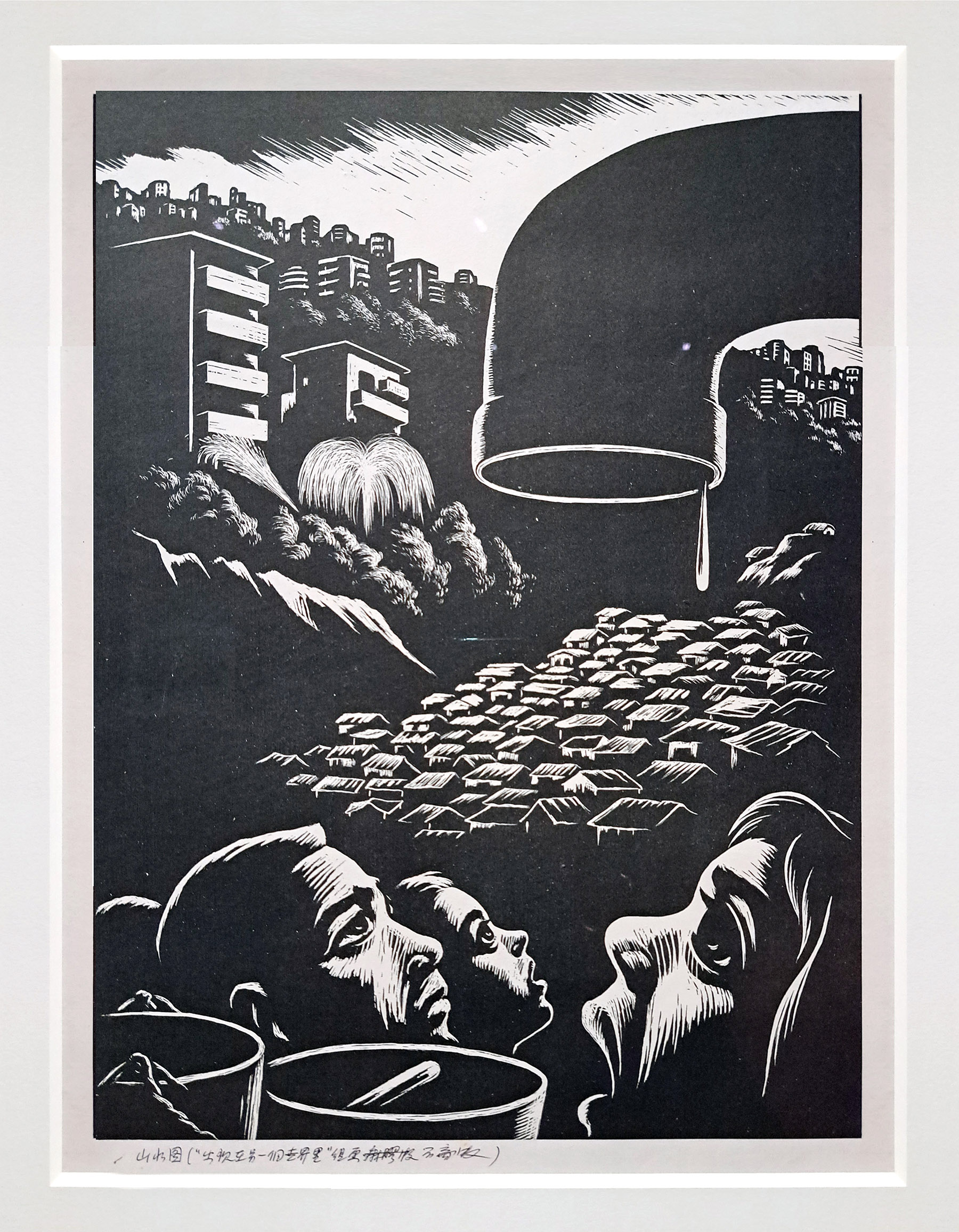

Huang’s Ship Terminal on the other hand is about getting up-close and uncomfortably personal with the income gap that was particularly glaring in Hong Kong in the wake of an influx of immigrants in the mid-’40s. Public housing facilities were scarce, as was the water supply. Huang’s 1962 portrait of children in a squatter settlement longingly gazing up at a tap releasing a thin trickle, contrasted with the fountain-embellished high-rise residences of the affluent in the background — from his What Takes Place in Another World series No 2 — illustrates the power of art in spreading a message about social inequalities.

Images and words

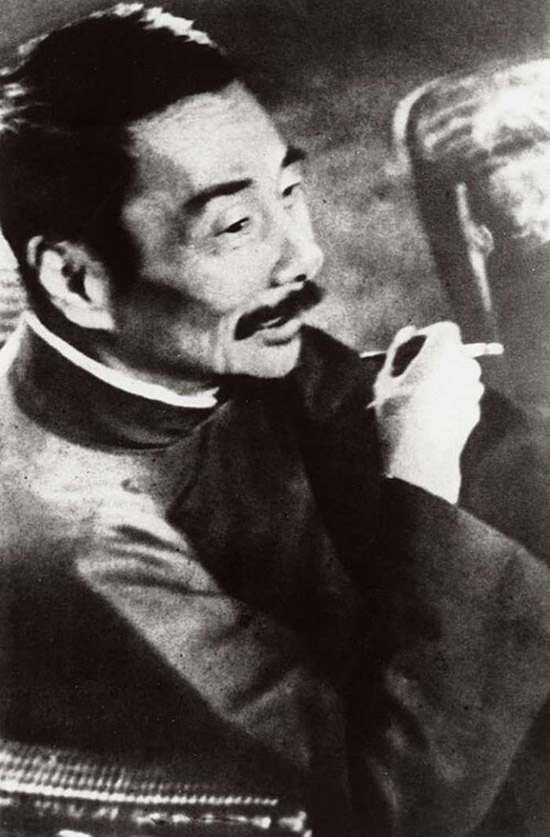

The story of how Guangzhou — from where many artists, including Huang, came to live in Hong Kong during the Chinese civil war (1946-49) — became a center for the New Woodcut Movement can be traced back to the movement’s founder, the iconic Chinese writer Lu Xun (1881-1936). Pang says that by inviting Japanese artist Uchiyama Kakichi to lead a woodcut workshop in Shanghai, Lu acted as a “catalyst”. Cantonese artists like Li Hua and Gu Yuan (1919-96) were inspired to embrace a medium capable of creating stark contrasts and bold, simplified figures and forms that seemed ideal for depicting the suffering of ordinary people during the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) as a result.

The exhibition features a photo of Lu, taken by Cantonese photographer Sha Fei, at the Second National Traveling Woodcut Exhibition in Baxianqiao, Shanghai, in 1936, just 11 days before the writer passed away.

Pang says the image went what’s called “viral” in modern parlance, both widely shared, and widely published in newspapers. “And because of Lu’s role in both the fields of art and literature, we have a woodblock print by Huang that shows Lu’s funeral and the collective mourning that happened around his death.”

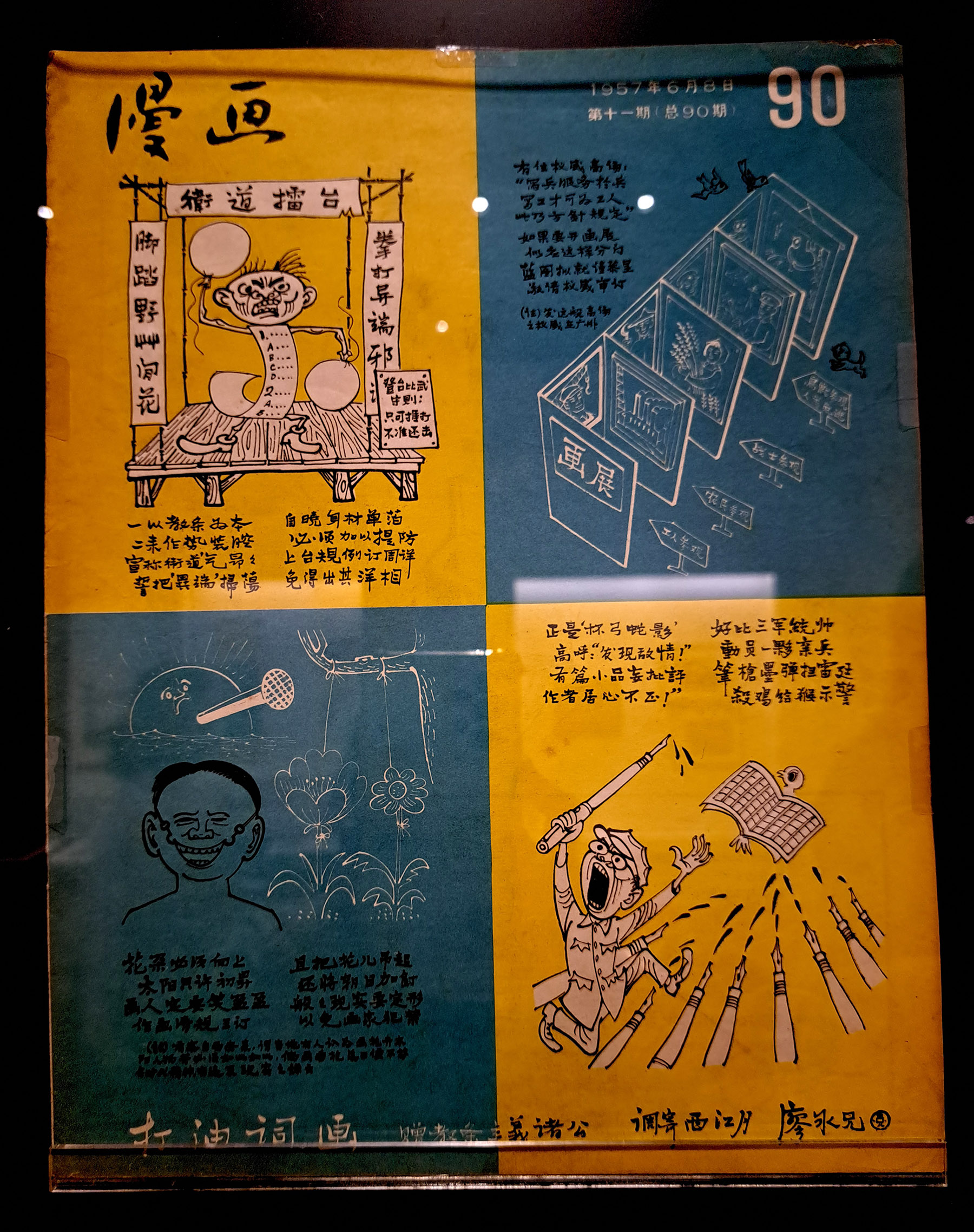

Huang’s contemporary, political cartoonist Liao Bingxiong (1915-2006), had also settled in Hong Kong around the same time as him. The M+ exhibition displays a couple of pages and a cover from the Manhua magazine, including sketches satirizing an artist’s right to freedom of expression. In one of his cartoons from 1957, The Technique Must Be So, the painter is a robot, controlled by a smoke-spewing official pressing the buttons.

Yeung points out that combining words and images is part of the time-tested tradition of Chinese ink paintings. “What is modern in our show, however, is how artists revisited that relationship in particular through the pictorials, as these were a way of spreading news and new ideas — using the immediacy of images to make the writing more effective. Besides images appealed to people who couldn’t read, reaching out to a broader audience.”

One of the oldest exhibits in the show is a piece of illustrated news about the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905. It appeared in Issue 9 of Current Affairs Pictorial, published by the Tongmenghui, a revolutionary party led by Song Jiaoren (1882-1913) and Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) that was trying to put an end to Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) rule in China.

Yeung says that the coming together of words and images is much more “dramatic” in the cartoons on display. For the words used in cartoons mark “a departure from the classical poetry in traditional Chinese painting”.

“Cartoonists use everyday language and a more colloquial way of addressing readers, combining words with humorous images, usually to convey serious moral lessons and political observations.”

Pang draws attention to an example of artist as book illustrator from the show. Guangdong province-born Yang Zhiguang (1930-2016), who went on to become a highly respected artist-academic, collaborated with Yin Guoliang (born 1931) from Shanxi province on an English-language edition of a 1961 “red classic” called Great Changes in a Mountain Village, set in an agricultural collective. “It’s a novel in two volumes, and for its English-language edition, the publishers very deliberately selected these artists to illustrate the publication because Yang is an ink painter in a realist style and so they were able to bring a sense of cultural sensitivity to the nature of the subject.”

Women in art

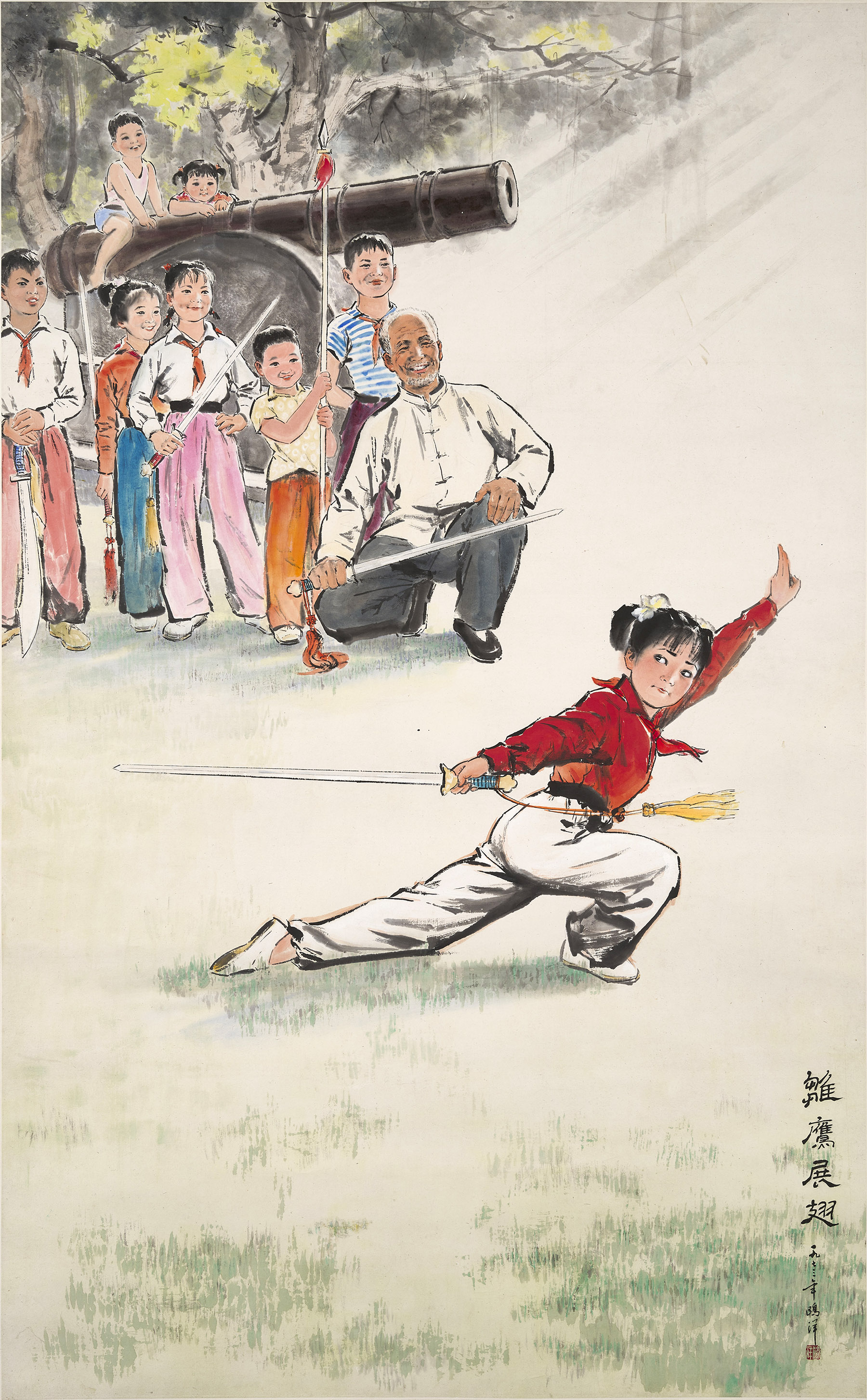

One of the most disarmingly feel-good pieces in the show is by Yang’s wife Ou Yang (born 1937). Titled Young Eagle Spreading Her Wings (1973), the ink and color on paper piece shows a confident young girl, demonstrating a martial arts move with her sword, while her fellow students await their turn. There is a cannon in the background, but the presences of children perched on it, and an appreciative and watchful instructor, lend a benign touch to a painting that is essentially propaganda art, if a slightly more nuanced one compared to the mainstream versions.

Yeung says, “During the ‘cultural revolution’, when artists had to paint propaganda images, the artist changed her medium from oil to ink, partly to free herself from some of the conventions and strictures on propaganda art. By painting in ink, she could basically pay attention to how ink painting can represent light and shadow, textures like grass and metal — things that classical ink paintings were not very good at.”

Another example of artists testing out the potential of their medium is Wong Siu-ling’s (1909-89) Sewing for You, a 1941 oil-on-canvas portrait of his then-wife. Pang points out that while the qipao-wearing woman in the painting appears in a modern context, she is sewing a Qing Dynasty-style robe, with a traditional ink painting hanging on the wall.

“So it’s a very self-conscious effort on the part of the artist, thinking about the relationship between the past and present, between tradition and modern art. At the same time, he could have been playing with the visual possibilities of what the medium of oil can achieve in terms of portraying the dress.”

Fang Rending’s (1901-75) ink and color on paper work, Mother and Child in the Rain, 1932, is easily one of the most aesthetically pleasing exhibits on show. Ironically, as Yeung points out, it is in fact “a depiction of suffering, of running away from famine or war”.

“His style is influenced by Japanese pictures of female beauties. However, there is a second painting by him made in 1959 where you see him making adjustments to depict a politically correct subject — a female worker in her hour of leisure, washing her feet. And then, in a third work, figures disappear altogether,” Yeung says, referring to Serving the People, circa 1966, which shows objects left behind by a Chinese grassroots official Jiao Yulu (1922-64), including notebooks and a copy of the selected works of Mao Zedong.

ALSO READ: Chronicles of a road retold

“So you see an interesting evolution — from idealized portraits of women to a politically correct depiction of women to a nonfigurative depiction.”

The exhibition also features a nude by Tan Yuese (1891-1976) — a Buddhist nun who returned to secular life at 31. Yeung says that the nude could be a self-portrait. “And if that is true, it might actually be the earliest, fully nude self-portrait by a Chinese artist.”

Done primarily in shades of red, rust and dark brown, the portrait’s style is close to European Expressionism. The mood is dark and somber. Yeung notes “an interesting tension between the Buddhist message — the idea of being encumbered by attachments — and eroticism, as in those days nuns living in the Buddhist nunnery that Tan was a part of were sometimes made to work as high-class courtesans. So it’s a very ambiguous painting, whether it was sexual or religious, or both.”

If you go

Canton Modern: Art and Visual Culture, 1900s-1970s

Dates: Through Oct 5

Venue: M+, West Kowloon Cultural District, 38 Museum Drive, Kowloon

www.mplus.org.hk

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com