Zhao Tongtong begins each school morning with a carefully timed ritual. At precisely 7:35 am, the 23-year-old postgraduate student exits her Shenzhen apartment near Shenzhen Bei — Shenzhen’s high-speed rail station — just in time to catch the 8:02 am train to Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Station.

Over months of practise, Zhao developed a shortcut to minimize her commute by making full use of the station's emergency lane reserved for late comers.

By 8:45 am, after a seamless MTR transfer, she arrives at Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU), sometimes grabbing a quick breakfast before her first class.

READ MORE: Cross-boundary commute — a long hard stretch

“I’ve kept this schedule for 10 months without a hitch,” says Zhao, an international tourism and convention major. “Living in Shenzhen is far more affordable — I have my own apartment and can order food deliveries whenever I want.”

Her monthly rent and utilities total just 4,300 yuan ($590), a fraction of the HK$15,000 some one-bedroom units near her campus now command. The 19-minute train trip cost her 75 yuan and she travels to Hong Kong three times a week on average.

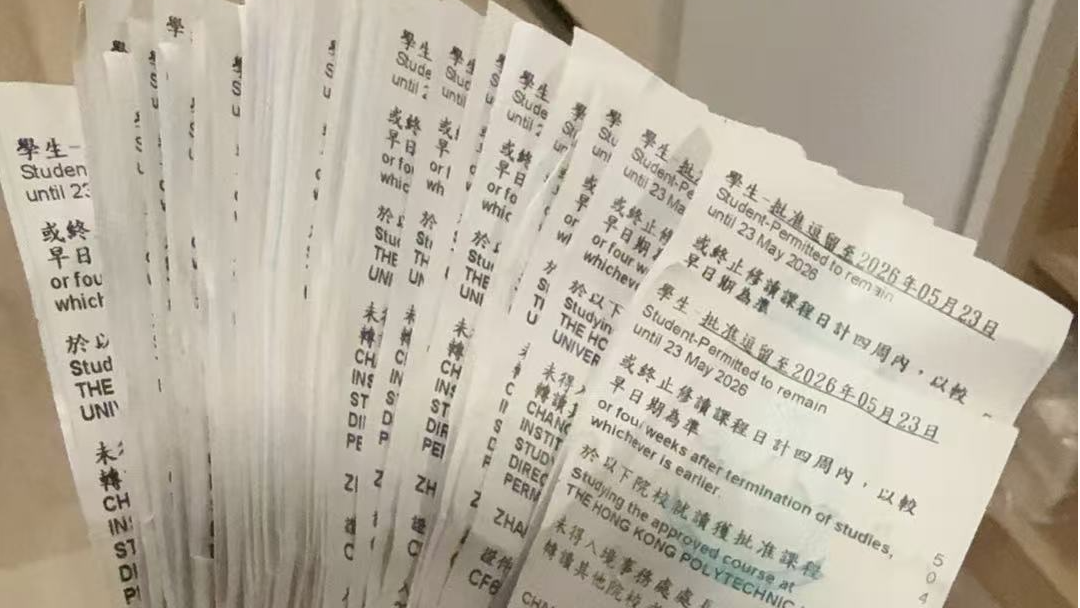

Zhao is part of a growing trend among Chinese mainland students pursuing degrees in Hong Kong while sidestepping the city’s exorbitant rents.

Drawn by Shenzhen’s lower living costs and efficient transport links, these cross-border commuters are redefining student life in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA).

Huang Sen, a recent Hong Kong Baptist University graduate, backed up Zhao’s story.

During his postgraduate year, he commuted four times weekly via MTR between Shenzhen’s Luohu port and his Hong Kong campus in Kowloon Tong.

The one-hour cross-border trip allowed him to attend evening classes until 9:30 pm and still return before the midnight boundary closure.

“If I had lived in Hong Kong for a year, my total education expenses could have reached nearly 300,000 yuan,” he says. “Instead, I spent around 230,000 yuan.”

Now working in Hong Kong’s public relations sector, Huang continues his cross-border lifestyle for the financial benefits.

He’s even turned his experiences into social media content, sharing commuter tips with his 13,300 followers on RedNote, a lifestyle platform popular among mainland youth.

“Many students commute to save money, or because they are interning at a Shenzhen tech firm, or simply to maintain their preferred lifestyle,” he notes. “When I started sharing these tips online, I was surprised by the overwhelming interest.”

Hong Kong’s appeal as an education hub continues to rise. The city jumped five spots to rank 17th in the QS Best Student Cities 2026 report, while five of its universities cracked the QS World University Rankings 2026 top 100 — led by the University of Hong Kong (HKU) at an all-time high of 11th.

From the 2024/2025 school year, Hong Kong can admit twice as many non-local undergraduates, with the cap doubled to 40 percent at its eight public universities, which has spurred demand for off-campus housing.

Recent analyses by local real estate agencies show rents near some campuses rising 10-20 percent in the months leading up to the new academic year in September.

A chronic shortage of on-campus housing exacerbates the problem. A 2023 Cushman & Wakefield report found that half of Hong Kong’s eight public universities have a student-to-bed ratio exceeding five.

With dormitory spots allocated by lottery — often limited to first-year students —most must rent privately from their second year onward.

Lau Chi-pang, associate vice-president of Lingnan University and a Hong Kong legislator, sees cross-border living as an innovative solution. His university actively encourages students to reside in Shenzhen, capitalizing on the Greater Bay Area’s “one-hour living circle”.

Lau’s optimism is fully checked out by reality. The university’s campus in Tuen Mun is geographically close to Shenzhen Bay — a stop away by cross-border bus.

Meanwhile, postgraduates near the university’s newly acquired downtown campus in the West Kowloon District —a short walk from the city’s sole high-speed rail station — can reach Shenzhen’s Futian station in just 14 minutes for 68 yuan.

“Postgraduates only need to be on campus about three days a week,” Lau says. “Transportation costs remain manageable.”

For universities further from the boundary, such as the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) in Clear Water Bay, repurposing underused commercial properties offers a potential fix.

Last month, HKUST acquired a 2,700-square-meter property near Admiralty — a central transport hub — to convert into teaching facilities for business students.

The move is expected to benefit the non-local working population seeking further studies.

Charles Ng Wang-wai, HKUST’s vice-president for institutional advancement, says the university is exploring multiple options, including negotiating with Kwun Tong property owners to transform vacant spaces into student housing or labs.

He also highlights a new government pilot scheme, introduced in June, to fast-track the conversion of hotels and commercial buildings into dormitories. The first facilities under this plan are expected to be ready by the 2026/27 academic year.

“These efforts align with our internationalization strategy,” Ng says. “We are fully committed to exploring all feasible solutions.”

The land use relaxation follows Hong Kong Metropolitan University’s 2024 purchase of a hotel near its Hung Hom campus to accommodate its growing non-local student population.

While students scramble for housing, the city’s private property market faces a record vacancy rate. A March 2024 Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government report revealed 57,900 vacant private units with the vacancy rate hitting 4.5 percent, the highest since 2010.

Hu Min, president of New Channel International Education Group, suggests authorities leverage this downturn by incentivizing universities to partner with private landlords for student housing.

Lau agreed, noting that converting private units into dorms could be a win-win.

READ MORE: Cross-boundary travel to peak during holiday break

A properly adapted apartment could house six students, each paying HK$6,000–8,000 monthly — yielding higher returns than traditional leases, Lau said.

With greater prestige comes more students — and more housing challenges. Yet Lau said he remains optimistic.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all solution,” he says. “Each university must innovate based on its unique circumstances.”

Contact the writer at lilei@chinadailyhk.com