Carpets from the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, take center stage at Hong Kong’s first major exhibition of Islamic art hosted by the Hong Kong Palace Museum. Chitralekha Basu reports.

As conflicts intensify in the Middle East, an exhibition that opened at the Hong Kong Palace Museum on June 18 is turning the spotlight on the reign of the Safavid shahs (1501-1736) and at a time when Iran used its patronage of the arts as a form of soft power. The exchange of diplomatic gifts not only helped build bridges between the nations represented by the giver and the recipient but also, sometimes, succeeded in forging connections, even if it was by default, with a third culture not directly involved.

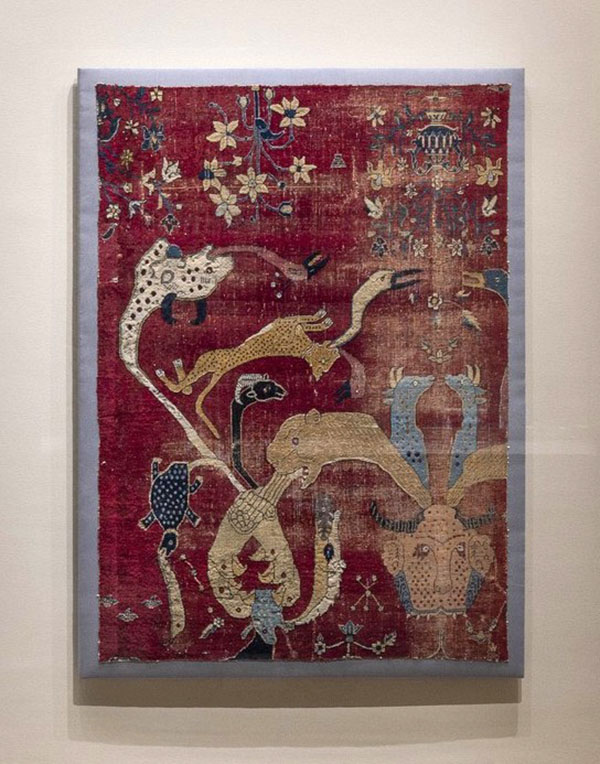

One of the exhibition highlights — a “hunting” carpet (circa 1610) from the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar — is a fine example of the confluence of a diversity of cultures in the Early Modern world. The piece was Shah Sulayman Safavi’s (reigned 1666-94) gift to General Francesco Morosini (1619-94), an illustrious naval commander who went on to become the most powerful man in Venice.

READ MORE: Step into the Arabian nights

MIA director Shaika Nasser Al-Nassr points out that “the carpet has a lot of motifs inspired by Chinese art, including lotus blossoms and cloud band motifs,” while the figurative animal motifs — lions attacking buffaloes, hunting dogs, peacocks, partridges, ducks, leopards and roosters — “are all inspired by Chinese culture”.

“This object shows how Islamic art was global and more interconnected with other cultures than we think,” she says.

Sustained connections

The Wonders of Imperial Carpets: Masterpieces from the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha show at the HKPM is the first large-scale exhibition of Islamic art in Hong Kong and also the first in a series planned as a result of a memorandum of understanding signed between Qatar Museums — which includes the MIA — and the West Kowloon Cultural District, of which the HKPM and M+ museum are subsidiaries.

“Appreciation and understanding of other cultures is really important to us. Also we wanted to show the intercultural connections between the Islamic world and China,” says the MIA director. “We chose carpets because of their artistic excellence. In this exhibition, they showcase the artistic exchange and influence between China and the three Islamic empires: the Safavid Dynasty (1501-1736), the Mughal Dynasty (1526-1857) and the Ottoman Dynasty (1299-1923).”

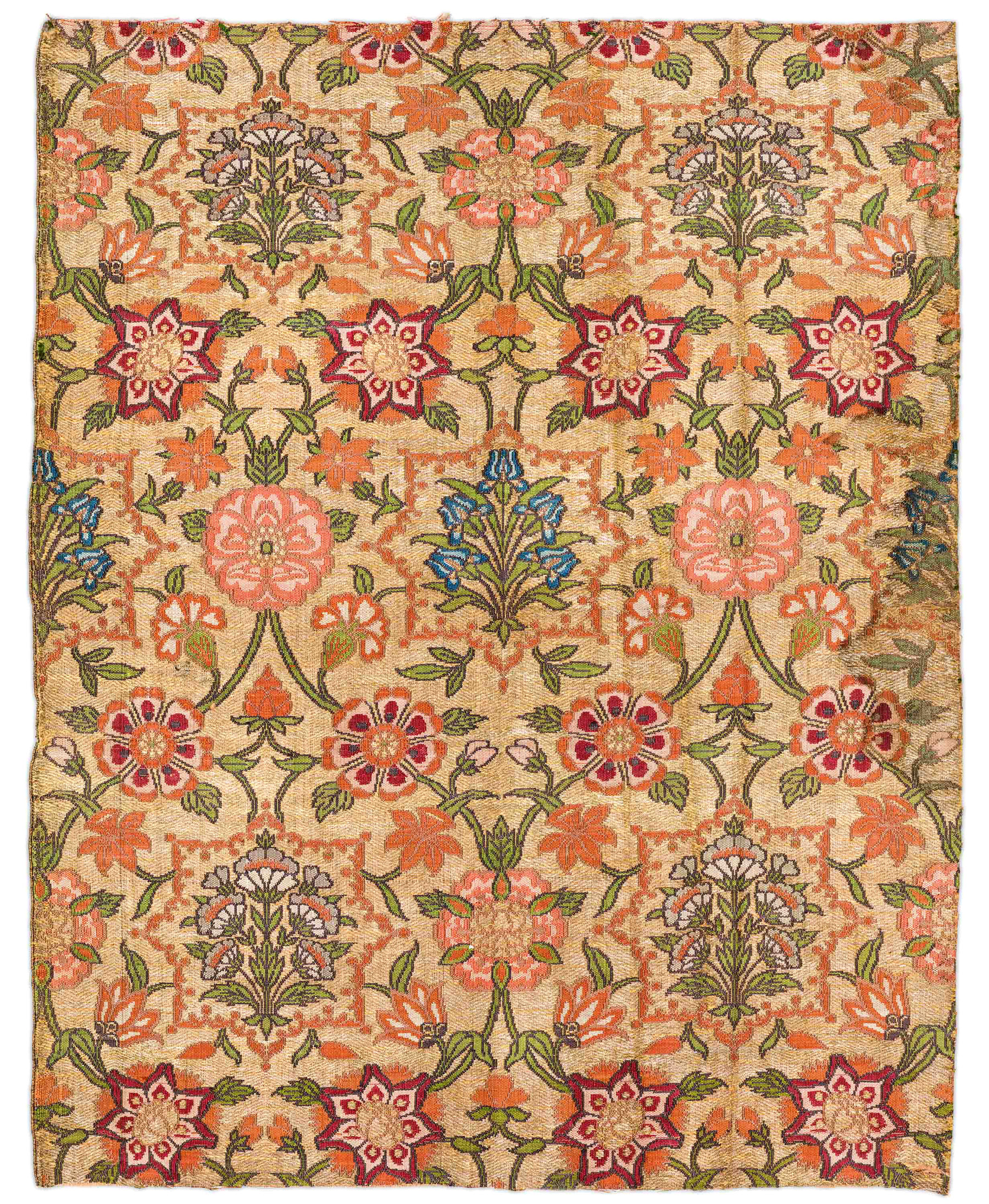

For her, the pairing of a floral carpet with gold and silver threads from the Qianlong period (1735-96) during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) — sourced from the Palace Museum in Beijing — and a piece of Safavid textile with pink, red and blue flowers, with metallic thread work (circa 1700-22) from the MIA collection epitomizes the central idea of the exhibition.

“The two pieces look extremely identical in terms of design and their floral patterns, despite being made in different regions and at different times,” she says.

She also recommends the late-16th-early-17th-century Turkish Çintamani prayer rug from the MIA collection as an exemplar of “the coming together of Hindu, Islamic and Buddhist cultural elements”.

While the piece derives its name from a portmanteau Sanskrit word, meaning “wish-fulfilling jewel”, its recurrent three-roundels-cluster motif is derived from Buddhist iconography.

“The Ottomans reinterpreted the motif,” says Al-Nassr. “For them, it represented good faith and power.” She adds that the Ottomans read the motif as a representation of the shape of a mihrab — a niche in the wall of a mosque — which points in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca toward which Muslims are expected to face when praying.

“So the piece shows how different motifs used in that prayer rug have been reinterpreted over time.”

One of the few purely religious objects in the exhibition, the prayer rug also bears an abstract representation of the Prophet’s sandals.

Through a Chinese lens

Most of the carpets featured in the show were part of a 2018 exhibition at the MIA. However, its current HKPM iteration looks at the story through the lens of China.

“The 2018 exhibition was focused mainly on the three empires and how art objects and artisans traveled across borders, as well as the influence of art diplomacy and trade on culture, but we wanted to make this one more relevant for the audiences of Hong Kong and the region that it was traveling to,” Al-Nassr says. “So we added the element of the influence of Chinese art on Islamic art and vice versa. Moreover, we added objects from the HKPM and the Palace Museum to tell this story of art, influence and exchange.”

Ingrid Yeung, an associate curator at the HKPM, says the show is designed in a way so that visitors — including a sizable section from the Chinese mainland — can relate to the content as soon as they walk through the door. For instance, one of the first things they see is a staple of traditional Chinese pottery — a flared-lip blue-and-white porcelain basin with floral scrolls from the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province. Crafted during the Yongle period (1403-24) in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the intricately painted porcelain piece with underglaze cobalt blue has been paired with a mid-13th-century Syrian silver and gold inlaid brass basin with intense engravings of zodiac signs from the MIA.

To make the exhibition more accessible by a Chinese audience with varying degrees of understanding of Islamic art history, Yeung had to furnish the show with “a lot of rather basic information”.

“I needed to explain what the Quran is and the different types of calligraphy used to write copies of them as well as the subtle variations of style these underwent in the 15th and 16th centuries,” she says. The exhibition also explains what the craft of gold-painted lacquer book-binding involves by providing detailed wall texts and a digital installation that allows visitors to virtually turn the pages of a 16th-century Quran from Safavid Iran, while the original, physical version from the MIA collection remains on display behind a glass wall.

A similar approach is taken to underscore the distinction between the weaving styles that lead to symmetrical and asymmetrical designs in carpets. The processes are explained through detailed diagrams. There is also a “Carpet Studio” learning corridor, where visitors can try their hand at digitally designing their “own carpet game”.

On a more fundamental level, Yeung thought it was fitting to explain “what Islamic art is”.

“It’s just a shorthand term used to describe art that can be religious or secular, created in historical Islamic domains,” she says.

Mighty motifs

The oldest exhibit in the show is probably a set of three gold plaques showing animals in combat (fifth-third century BC) from the HKPM’s Mengdiexuan collection. These objects could have been buckles, or a piece of armor, used by nomads who roamed across the Eurasian Steppe. In the exhibition, the predator-and-prey combination pops up two millennia later, resonating with the hunting leitmotif in a 16th-century Ardabil-Sarre animal carpet, as well as in the image of a lion overpowering a bull on a 17th-century Iznik tile — both from the MIA collection.

Yeung notes that in pre-Islamic and Islamic visual cultures, images of strong animals attacking weaker prey — such as the tiger and a lion ganging up on a stag leitmotif in the Ardabil-Sarre carpet — connote the power of the ruler over his enemy, and hence were popular choices as diplomatic souvenirs.

The most recent cultural link between China and the MIA is probably the museum’s spectacular waterfront building in Doha, designed by Chinese American architect IM Pei (1917-2019). The structure’s clean-cut, geometric form — stacked boxes, accentuated by the combination of octagons and squares — takes its cue from the spare, minimalist ideals of Islamic philosophy, rather than the elaborate and intense aesthetic of Islamic calligraphy or the spiraling arabesques of Islamic art.

Al-Nassr reveals that after the MIA’s 2022 relaunch with an augmented collection, there wasn’t enough room left in the Pei-designed building to display the 16-meter-long Kevorkian Hyderabad carpet from Deccan, Mughal India — the star of HKPM’s Imperial Carpets show, according to Yeung. The 17th-century wool-pile-on-a-cotton-foundation piece portrays an elaborate garden, with a medallion-shaped pond in the middle, saturated with fish. The stylized, elongated fish shapes and intense weave of vegetal motifs seem inspired by the iconography typical of the paradisiacal gardens in Persian art.

While the carpet — likely to be the handiwork of migrant Iranian weavers who worked in the imperial workshops in Mughal territories in 17th-century India — does not have an obvious Chinese connection, at least one of its companion pieces resonates with the depiction of China as a land of exotic wonders in literature and art of other cultures. The latter is a fragment of a carpet showing a tiger and a pair of blue, horned beasts emerging from a monster’s head. The tiger is swallowing a parrot whose claws clutch at another blue creature that has a crocodile sprouting from its head. The crocodile, in its turn, has a smaller animal caught between its teeth. The wall text says that this bizarre depiction of the food chain could be alluding to the waq waq tree mentioned in Persian and Arabic literatures. The fruits of this tree, growing on an island in the sea of China, are animal heads.

More fantastic beasts can be found in the exhibition’s Ottoman Dynasty section, where a Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) ceramic jar showing a phoenix among clouds, from the Palace Museum, is placed next to a 16th-century watercolor and ink painting of a dragon and other mythical creatures from the MIA.

“By putting them side by side, I want to convey the idea that we have these fantastic creatures in the human imagination and sometimes they take on similar forms,” Yeung says. Though in this case, one object isn’t necessarily inspired by the other, the curator says that they demonstrate that “there are certain similarities in the human imagination that cross the boundaries of time and space”.

Emperor as poet

The historical and cultural significance of the flow of objects, people and ideas between China and the Islamic worlds in the Early Modern period is symbolically stated on the surface of one of the exhibits contributed by the Palace Museum. A 10-lobed jade bowl with acanthus leaf handles crafted in 17th-century Mughal India had landed in the Chinese imperial collection around a century later, stirring the poetic sensibilities of the Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1735-96).

In a poem, inscribed on the bowl’s inner surface, the emperor imagines the object to have passed through the hands of “the immortals of the West”, who used it to perform sacred rites before it reached China.

ALSO READ: Tapestry of cultural connections

Such an observation points to a time when transborder exchange of cultural objects could have formed the foundation of mutual respect and admiration between nations, even when there wasn’t necessarily a strategic or diplomatic angle involved.

If you go

Wonders of Imperial Carpets: Masterpieces from the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Dates: Through Oct 6

Venue: Gallery 9, Hong Kong Palace Museum, 8 Museum Drive, West Kowloon Cultural District, Kowloon

www.hkpm.org.hk/en/home

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com