Centuries of artistry turned the Mogao Caves into silent witnesses of China's unfolding cultural and political saga, Zhao Xu reports in Dunhuang, Gansu.

One theme that continually echoes through the world-renowned Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, Gansu province, is the passage of time. Tour guides often point out that the black elephant and black horse depicted in two frescoes — illustrating the mythical birth of Shakyamuni, the historical founder of Buddhism, and his departure from a life of luxury in pursuit of enlightenment — were originally painted white. Their darkened appearance today is the result of oxidation over a millennium.

The same chemical process affected the lead white pigment once applied to certain facial features to enhance structure and dimensionality — similar to how makeup is used today. As these white highlights darkened over time, some faces in the Dunhuang frescoes exude an eerie, haunting beauty.

However, the most powerful reminder of the progression of time lies not in the transformation of color but in the visible layering of history itself, as centuries of devotion and artistry accumulate one atop another, says Zhong Na, a senior tour guide who has visited the caves countless times over the past 20 years.

READ MORE: Buddha's gaze into eternity

According to Zhong, though new caves were continually carved starting from the mid-4th century, it was common for each new generation of artists to add to the visions of those who came before — plastering over the works of their predecessors to paint their own sacred reflections of the Buddhist realm.

Known as chongceng bihua, or "multilayered frescoes", the phenomenon finds a striking parallel in the history of Western oil painting. Through techniques like X-ray fluorescence and infrared reflectography, conservators have discovered hidden compositions beneath the visible one — a practice known as pentimento (from the Italian pentirsi, meaning "to repent") in which artists reconsider their vision or repurpose a canvas. At times, these earlier images were painted over simply out of practicality, such as saving materials.

In Dunhuang, this practice has played a vital role in preserving the past. The top layers of murals, added by later generations, help protect the underlying artwork, slowing oxidation and discoloration. As a result, when the surface layer eventually deteriorates, the exposed lower layers often remain in relatively good condition. Even without the top layer falling away, the different strata can still be glimpsed along the edges, where broken portions reveal the cross-sections of the walls.

"In this sense, the Dunhuang frescoes are like a book — each page capturing a distinct era bound together by the thread of history," says Zhong. "It tells something about a cultural tradition that grounds the ancient Chinese civilization."

Interestingly, the same layering applies to the floors. In Cave 96 — home to the largest Buddha statue in Dunhuang — floors built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) rest atop those from the Ming (1368-1644), which in turn overlay earlier layers from the Yuan (1271-1368), Xixia (Western Xia) (1038-1227) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, dating back to the cave's original construction in the late 7th century. "We've had to revise the recorded height of the cave multiple times with each discovery of a deeper floor beneath," Zhong admits.

Vital crossroads

Among these regimes, the Xixia was established by the Tanguts, a historical ethnic group in China. Dunhuang's location, over 1,000 kilometers from the Chinese heartland and a vital stop along the ancient Silk Road made it both a cultural crossroads and a fiercely contested region among central and local authorities. This political complexity is vividly reflected in the grotto murals.

Take Cave 61, for example. Commissioned by Cao Yuanzhong, the de facto ruler of Dunhuang from 944 to 974, the cave features a wall dedicated to prominent women of the Cao family — including those married off and those who married into the family as part of political alliances with neighboring powers. Their identities and affiliations are distinguished by the varied styles of their headdresses.

"It takes a learned, discerning pair of eyes to discover all the hidden political messages," says Zhong, noting that when Cao appeared in a cave of another grotto complex about 100 km east of the Mogao Grottos, he chose to be depicted wearing a hat and robe seemingly borrowed directly from the royal wardrobe of a contemporary Northern Song (960-1127) emperor — rulers of the Chinese heartland at the time.

"The Cao family rulers of Dunhuang had consistently identified with and subscribed to the authority of the central Chinese dynasties," says Rong Xinjiang, a Silk Road scholar.

It's worth noting that a popular song, believed to have been performed during New Year celebrations in Dunhuang around the 9th or 10th century, opens with the line: "Hexi is the old land of the Han emperors".The Hexi Corridor — located in present-day Gansu province in northwestern China — is a vital stretch of the ancient Silk Road, at the western end of which Dunhuang lies. Here, the "Han emperors" refers to the establishment of the Dunhuang Commandery during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), several decades after the mission of Zhang Qian, the pioneering envoy who first charted the route in the first half of the 2nd century BC.

Dunhuang was officially incorporated into Tang territory in the late 7th century but fell to the expanding Tubo regime during Tang's internal turmoil in the late 8th century. Tubo control, lasting about half a century, began to crumble after the assassination of its last ruler in 842. Between 848 and 851, local strongman Zhang Yichao defeated the Tubo forces and reclaimed Dunhuang. Following his victory, Zhang immediately dispatched people to inform the Tang court that Dunhuang (then known as Shazhou) had been re-integrated into its territory.

Of the multiple delegations Zhang Yichao sent — some sources suggest there were as many as 10 — only one successfully reached Chang'an, the Tang capital. That mission was led by a Buddhist monk entrusted with the task by his mentor, the eminent monk Hongbian, a staunch supporter of Zhang Yichao, a devout Buddhist.

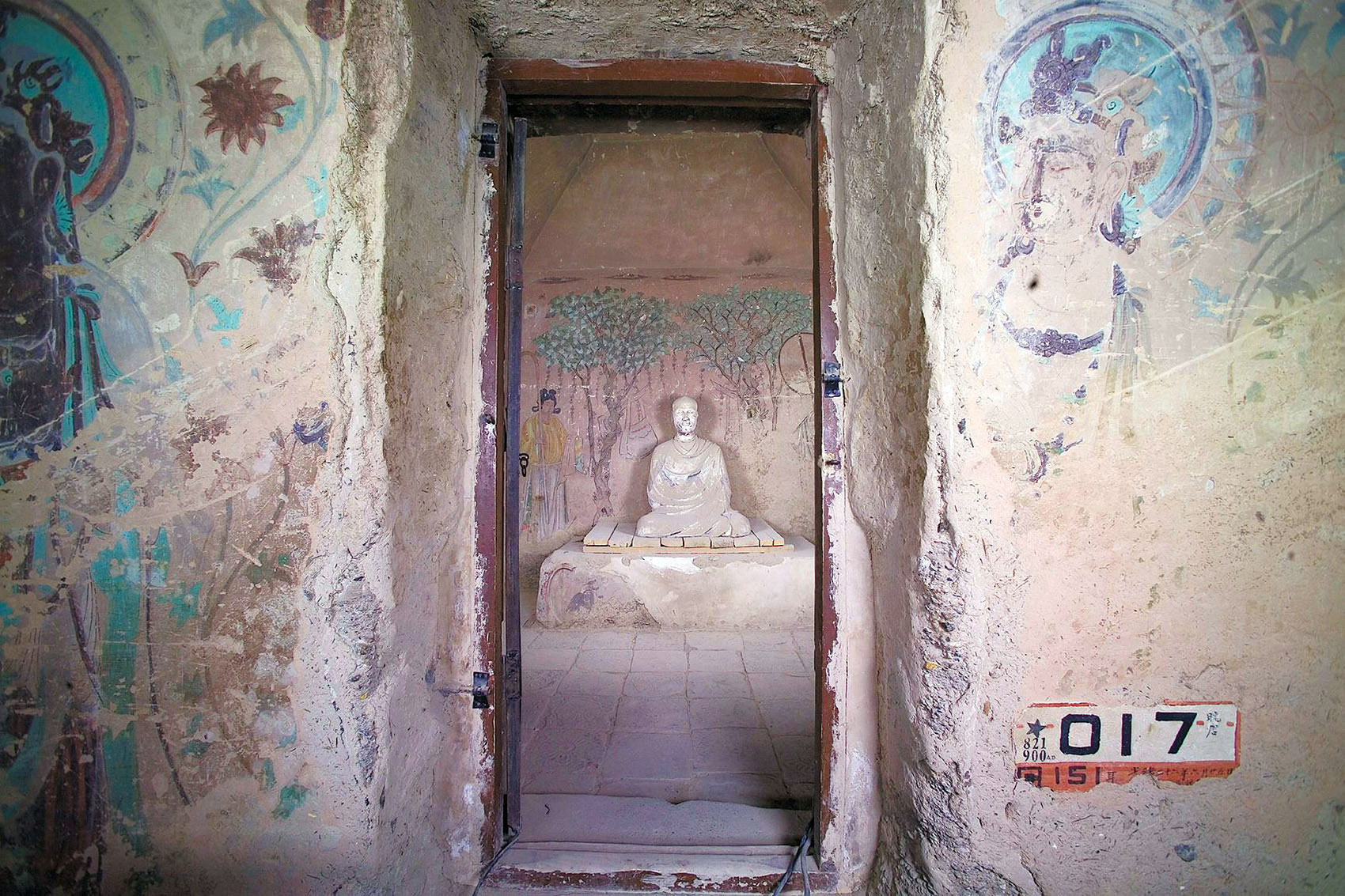

Today, a stucco statue of monk Hongbian presides over Cave 17 in Dunhuang. Tucked into the north wall off the entrance corridor to Cave 16 — the largest existing cave from the Tang Dynasty — Cave 17 measures no more than 6 square meters and yet, it is indisputably one of the most renowned Mogao caves. When it was first discovered in 1900, it was packed from floor to ceiling with more than 50,000 manuscripts, paintings and prints — earning it the title "The Library Cave" by which it is internationally known today. These materials form one of the largest repositories of religious, scientific and literary texts from the medieval period, offering invaluable insight into life in China and beyond. Today, they are housed in museums across Europe, North America and Asia.

A life-size statue representing Hongbian was originally discovered a few stories above Cave 17 and relocated to the cave in the 1980s after research revealed that it had always been intended to reside there.

Inside the statue, a small silk pouch containing Hongbian's ashes was found, along with official documents that attest to the statue's identity, says Zhong.

"These documents echo the content of a stone tablet embedded in one of Cave 17's walls, leading researchers to believe that the statue must have been removed from the cave at some point to make room for the manuscripts, while the stone tablet remained behind," she says.

Ushering in a golden age

The Mogao Caves do not lack grandeur — the tallest Buddha soars 35.5 meters, and 492 of the 735 surviving caves feature painted walls and sculptures. Even the modest Library Cave contains sparse wall paintings.

According to Zhong, emperors of China's short-lived Sui Dynasty (581-618) — which reunified the country after a long period of fragmentation — sought to standardize Buddhist practice and imagery. Unsurprisingly, they favored grandiosity, ushering in a golden age of opulence in Dunhuang mural art that continued to flourish well into the Tang Dynasty.

The influence of Indian Buddhism is on view in Dunhuang — the grotto caves themselves are rooted in the design of Chaitya Hall, a Buddhist prayer hall in ancient India typically carved into hillsides. These halls featured barrel-vaulted roofs visually supported by ribbed arches resembling wooden beams, and a stupa at one end for circumambulation — walking around the stupa in reverence, explains Zhong.

"All of these elements were preserved in Dunhuang. On the other hand, the imprint of Chinese culture is unmistakable. Among other details, the transformed visages, physiques and attire of the statues reflect the growing confidence with which Chinese artists and artisans expressed their own vision of the Buddha and his realm — ultimately making Dunhuang an emphatic footnote in the narrative of Chinese cultural and political history."

With all that said, it is often in the quieter corners of the caves that one is reminded of what compelled a monk named Yuezun to carve what is believed to be the very first Buddhist cave in 366, which would later become the Mogao Caves.

"Legend has it that Yuezun saw a nearby mountain bathed in a golden glow and believed it to be a divine calling from the Buddha," says Zhong.

"He responded by taking his chisel and carving into the sandstone cliff, creating what is believed to be the very first Buddhist cave in Dunhuang. Though we cannot locate it today, that cave was likely a small meditation cave — just large enough for one person to sit, with a height that accommodated only a seated figure."

ALSO READ: Repairing the past, restoring our future

Today, similar meditation caves can still be found in the Mogao Caves often tucked into the side or back walls of larger caves, their view sometimes obscured by stupas built inside for circumambulation. According to Zhong, a meditative monk would spend months in such a cave, with food brought in to sustain them.

In the 2nd century BC, upon being made a commandery by a Han emperor, Dunhuang, which in Chinese implies greatness and magnificence, was named.

When asked about the origin of the name "Mogao", Zhong says: "We don't know for certain, but some believe this place was once called Mogao village. Other researchers have pointed to the literal meaning of the term 'Mogao', which can be translated as 'no higher (than)'.

"There's no merit higher or greater than creating a space devoted to the worship of the Buddha — that could be what it meant."

Ma Jingna contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn