Determined to keep traditions alive, heritage-based architect finds new medium of expression, and a growing audience, after retiring, Yang Feiyue reports.

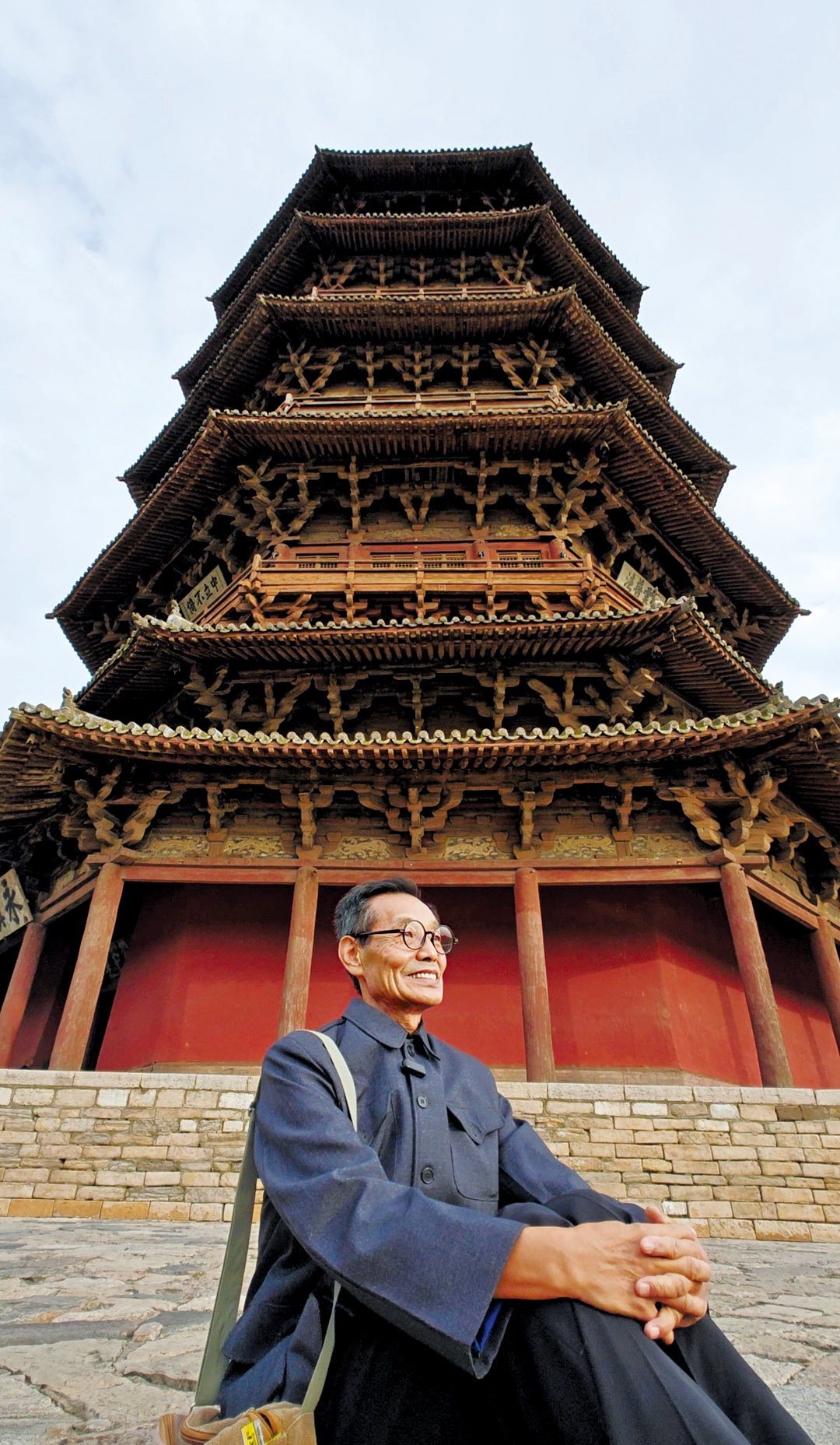

Bathed in the honeyed glow of the mid-March sun, 75-year-old Wang Yongxian explains the millennia-old Yingxian Wooden Pagoda to his 1.5 million followers in a video, as if introducing an old friend.

"This isn't just wood and nails, but a living record of Chinese ingenuity," says the man who drove more than three hours from his home in Taiyuan, capital of Shanxi province, to visit the towering marvel of engineering.

A retired structural engineer and cultural heritage expert, Wang has dedicated his retirement years to a new kind of preservation: digital storytelling. In the past two years, he has taken to livestreaming to introduce young viewers to the ancient knowledge embedded in China's architectural relics.

Today, his subject is one of the world's tallest and oldest all-wooden pagodas, which was built in 1056 and has miraculously withstood centuries of war, weather, and earthquakes. As he manipulates a scaled-down replica of the pagoda and zooms in on the graceful overhangs on each tier, Wang explains how, in the absence of nails, interlocking wooden brackets known as dougong, a technique perfected over centuries, account for flexibility and endurance.

READ MORE: Joining ingenuity with culture

Wang has formed a special bond with the pagoda since he became involved in its protection and restoration in the early 1990s.

"This historical wooden pagoda is a rare treasure shaped by the passage of time, bearing the weight of culture and the knowledge of our ancestors. However, centuries of wind, frost, rain, snow, and earthquakes have left it scarred and weathered. Today, its structural safety faces serious challenges," he says.

One of the most contentious issues, Wang explains in the video, is whether to implement a full dismantling and overhaul of the pagoda, which some believe is the only way to fully address the risks posed by its age and increasing tilt.

But Wang is firmly against it.

"A complete dismantling would be disastrous," he warns, adding that such an approach carries four major dangers, ranging from the loss of historical information and structural safety, to impairment of the pagoda's authenticity and spirit, and violation of legal principles.

"The wooden components contain a wealth of historical data — craftsmanship, signs of wear, marks of the era. Replacing any of these during dismantling means that irreplaceable historical evidence is lost forever," Wang says.

"Plus, it is a masterpiece of traditional mortise-and-tenon architecture. Dismantling it requires exceptional skill. A single mistake during reassembly could lead to irreversible structural damage," he adds.

Additionally, China's newly revised cultural relics protection law demands minimal intervention and prohibits altering a heritage site's original state, he says.

Years of experience have led Wang to come up with a careful alternative: the traditional correction and restoration approach, which can help correct the pagoda's tilt without taking it apart.

"This plan avoids disassembly, preserves the structure's original state, and addresses the root safety concerns," he says, adding that it could significantly cut costs, and shorten repair time while retaining the greatest amount of historical authenticity.

Born and raised in Shanxi, Wang became involved in the preservation and restoration of ancient buildings in 1972. His footsteps have echoed through the halls of many of the iconic historic sites across the province, including Foguang Temple in Wutai county, Chongfu Temple in Shuozhou, and the Yingxian Wooden Pagoda.

Shanxi boasts the highest number of ancient architectural relics in China, and is home to more than 28,000 sites, among them, more than 82 percent of the country's surviving wooden structures built during or before the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

"These structures represent a vast and invaluable cultural inheritance passed down by our ancestors," Wang says.

However, the sheer volume of ancient buildings has made preservation a formidable challenge. Many of them have suffered from years of neglect and severe deterioration.

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, cultural heritage authorities have initiated large-scale rescue and restoration efforts to protect irreplaceable assets. For decades, Wang has been at the forefront of this mission.

He has contributed to the surveying, mapping, conservation planning, and restoration of many national level protected sites built from the Tang (618-907), and Song (960-1279) to the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

Among his most notable achievements, he was chief organizer and participant in the full-scale disassembly and restoration of the Shengmu (Holy Mother) Hall at the Song Dynasty Jinci Temple in Taiyuan, as well as the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) Chongfu Temple in Shuozhou.

Both projects involved the development of systematic conservation strategies and the resolution of complex structural issues, including foundation settlement, beam misalignment, and component degradation.

These efforts revitalized architectural masterpieces that had languished in critical condition and returned them to their former glory.

He later became head of ancient architecture project management at the Shanxi Cultural Relics Bureau, and played a key role in establishing protection standards for ancient structures.

Beyond hands-on restoration work, Wang also pioneered an innovative model for training a new generation of skilled craftsmen, which emphasizes the integration of hands-on experience, project management expertise, and a strong sense of responsibility.

He says he wants to instruct his young audience what his mentors did to him. At the start of his career, Wang envied classmates living in the city, working in comfortable offices and earning better salaries.

"In contrast, my working conditions were tough back then — dirty, exhausting, and poorly paid," Wang says.

But all that changed while accompanying architectural scholar Luo Zhewen on a trip across Shanxi, when Wang saw Luo, then in his 60s, fearlessly climb the beams of the Yingxian pagoda to study its structure up close. That moment of devotion and passion struck a chord with the young man.

"Learning directly from such a dedicated mentor was eye-opening," he says, adding that from then on, the idea of leaving never crossed his mind again.

He views traditional buildings not merely as structures, but as a cultural encyclopedia. "Each one embodies layers of history — politics, economy, religion, art, and craftsmanship. It's an expression of China's ancient civilization," he says.

Though he officially retired from the Shanxi bureau in 2000, Wang didn't leave work behind. Drawing on decades of field experience and the invaluable techniques he learned from veteran craftsmen, he wrote a series of books and academic papers to document traditional restoration methods.

He also began teaching a course on conservation and restoration of ancient buildings at Taiyuan Normal University.

His students' enthusiasm for the subject encouraged him to explore new ways of making ancient architecture more accessible, especially to the younger generation.

At their suggestion, Wang started a social media account called Dougong Class about two years ago.

For the man in his 70s, entering the world of vlogging was no small feat but with guidance from his grandson, he has learned how to operate filming equipment, edit videos, and share content online.

But mastering technology was just the first challenge.

"I couldn't just recite complex theory," Wang says. "I had to make it fun, make it understandable — only then would people listen."

So he began using models that could be dismantled and hand-drawn diagrams to break down complicated architectural elements like dougong brackets, hip-and-gable roofs, and large beam structures.

His accessible and creative approach quickly captured public attention. In 2023, the viral success of the video game Black Myth: Wukong sparked a surge of interest in traditional architecture. Wang's account rode the wave, picking up over 20 million views and helping cultivate an online community of architecture enthusiasts.

So far, his videos have amassed more than 80 million views across different platforms.

Yang Xiaofan, an architecture student from Guangzhou, Guangdong province, is one of Wang's followers.

"His videos dissect every bracket set … helping me grasp not just the 'how' but the 'why'," Yang says.

ALSO READ: AI used to help preserve China's oldest wooden pagoda

Du Yushi from Liaoning province says she binge-watched Wang's videos before visiting Shanxi. "Seeing the Jinci Temple brackets in person after his explanations made the trip unforgettable."

Wang's wife Yao Zi'e is also supportive of his work. "A fulfilling life leaves the world better. This work gives him purpose — you see it in his energy and health," she says.

Wang also passed the driver's license in 2023 to better access heritage sites, most of which are tucked away off the beaten track.

Speaking of his drive for teaching after retirement, Wang says he'd like to help preserve the vanishing techniques of master craftsmen.

"It pains me to see irreplaceable skills fade away with their practitioners," says the man who describes himself as having the spirit of a 20-year-old. "I'm rooted in tradition but embrace new ways."

"To me, a blackboard and a camera lens serve the same purpose, both are vehicles for passing on knowledge. The stage has just grown bigger, and with it, my responsibility."

Contact the writer at yangfeiyue@chinadaily.com.cn