An alarming rise in cyber sexual violence against minors has sparked disquiet among communities worldwide. Experts have called for tougher laws against offenders, as well as broader sex education, to help high-risk groups and prevent the problem from getting out of hand. Oasis Hu reports from Hong Kong.

Editor’s note: We are witnessing a distressing upsurge in cyber sexual violence, such as stalking, harassing, grooming, nonconsensual sharing of intimate images and even sextortion, with severe consequences for the victims. In the first of a series of reports, we delve into the problem of online abuse of minors in Hong Kong, with experts worried that this may be just the tip of the iceberg.

Cyber sexual violence against teenagers and juveniles is rearing its head across the globe, and Hong Kong is no exception.

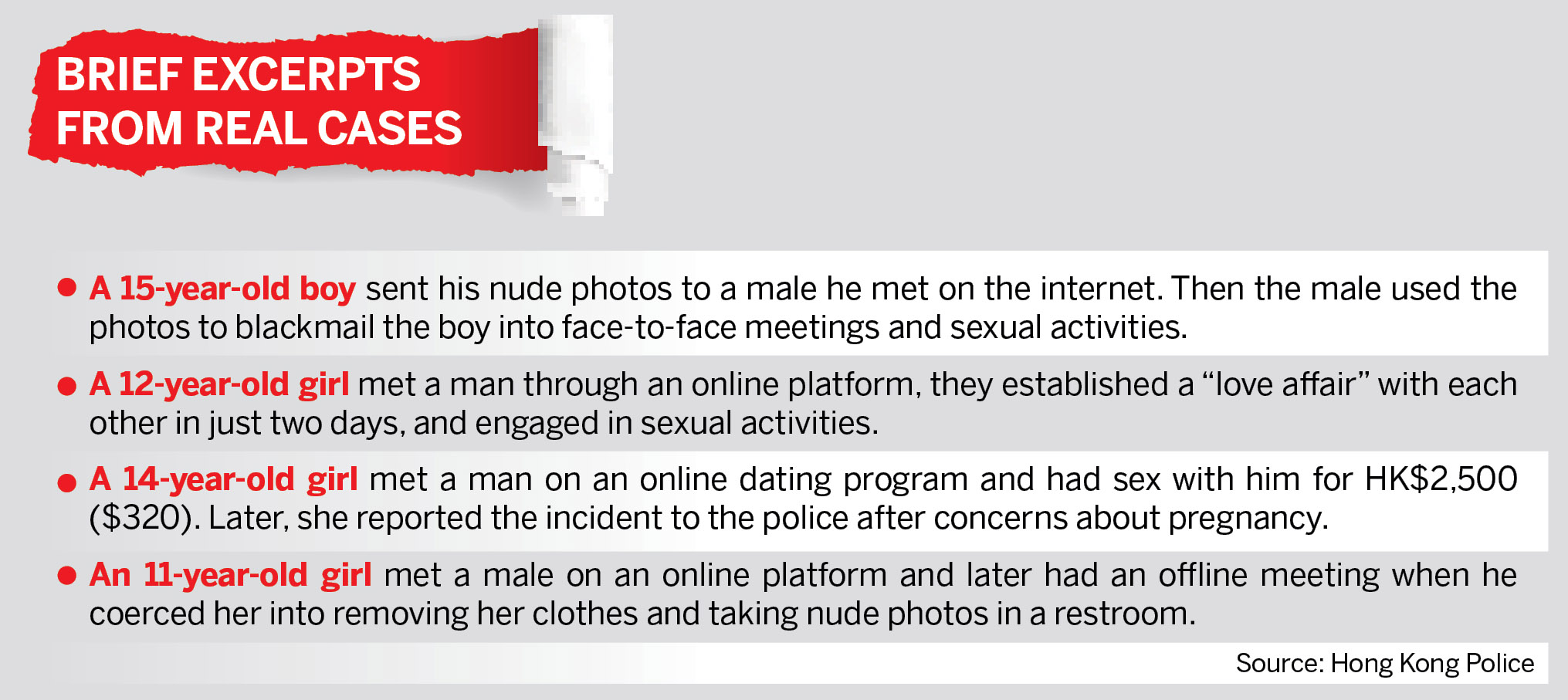

In one case, a teenage girl was totally oblivious to the fact that her intimate photos and videos had long been disseminated on the internet until the police went to her home to probe an online child pornography case.

It emerged that while in primary school, the girl had fostered a friendship online with a boy student. They had frequent cyber chats, leading to her being convinced to enter into a “romantic relationship” with him.

The unwary victim was also asked to send nude photos of herself. Blinded by the illusion of a “love affair”, the girl agreed, thinking that their interactions were solely confined to the digital realm. The boy went further by coaxing her into recording videos of herself engaging in explicit acts. She also did what she was told.

However, the pair eventually lost touch with each other as they were attending different middle schools. The girl kept those encounters to herself, confiding in no one. Her plight came to light when police officers appeared at her doorstep. Her mother was told that an investigation into an online child pornography case had unearthed evidence linking her daughter to explicit videos.

The moment of truth arrived as the girl’s family learned what had happened. The mother tried to downplay the story, pleading with the police to handle it discreetly and telling her daughter not to mention it again. But, the victim had been swarmed with apprehension, leaving her in deep trauma and forcing her to seek help.

She approached Phyllis Chan Kwok-ling, a specialist in psychiatry and honorary clinical associate professor at the University of Hong Kong’s Department of Psychiatry.

Chan recalls that the girl, then aged around 16, had exhibited severe social withdrawal and self-blame. The victim also had to grapple with intimacy issues, experiencing intense discomfort in her interactions with other boys.

In handling the case, Chan says she was overcome by a deep sense of compassion.

The psychiatrist lamented the lack of adequate education about online sexual abuse in society, causing the girl to underestimate the dangers on the Internet. It saddened her that nobody respected the girl’s emotions, including her mother and the officers involved in the probe. What was particularly disheartening was that she had come across a number of similar cases in the past few years.

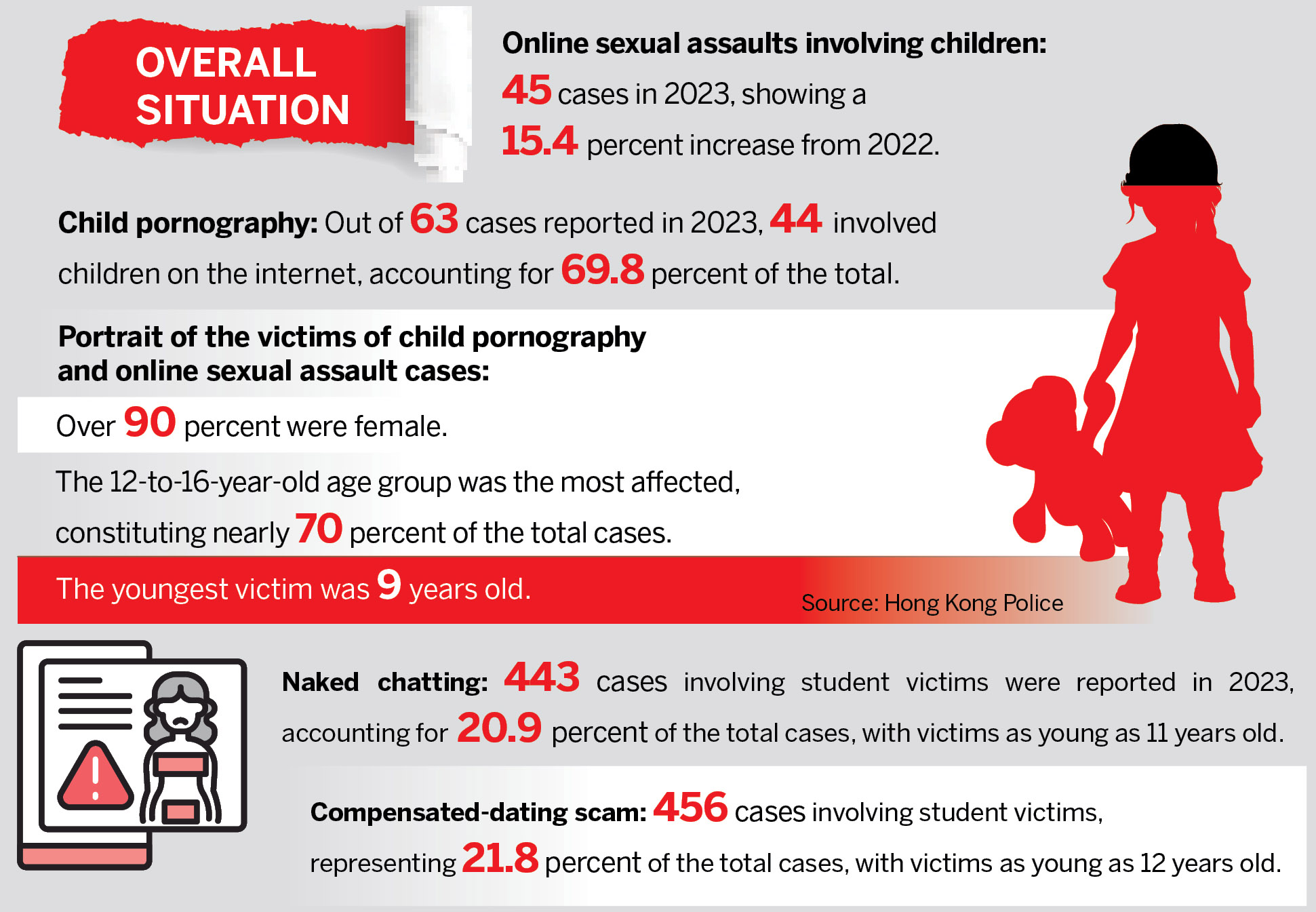

According to Hong Kong Police Force statistics released in March this year, a growing number of children in the special administrative region had experienced cyber sexual violence over the past few years. There was a 15.4 percent surge in sexual assault cases linked to children’s online activities, with 45 cases reported last year, compared to 39 in 2022.

More than 90 percent of the young victims of online sexual abuse and child pornography cases were female. The most affected age group ranged from 12 to 16 years, accounting for nearly 70 percent of the total number of victims. There were 443 cases of extortion arising from naked chatting and 456 cases of compensated dating fraud targeting students in 2013. These accounted for 20.9 percent and 21.8 percent, respectively, of the total number of cases without age limitations. The youngest child victim was just nine years old.

Illusory sexual consent

Jessica Li Chi-mei, an associate professor at the Department of Applied Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, led a year-long study on online sexual abuse against children in the SAR. The study, launched in April, examined nearly all reported cases in the past decade and interviewed about 80 staff members of primary and secondary schools.

Li’s research identified four prevalent forms of cyber sexual violence against children in the city. Sexting means that children receive or forward sexually explicit messages via the internet. Online grooming exploits children by gradually introducing sexual content, leading to explicit sharing of images. Sexual extortion involves coercing teenagers into providing favors or money, while live online child sexual abuse refers to broadcasting real-time exploitation, she explains.

In real life, sexual violence against children encompasses a more far-reaching spectrum. It includes any action that causes negative emotions or physical harm to a victim, says Doris Chong Tsz-wai, a social worker and executive director of the RainLily Sexual Violence Crisis Centre. When such violence occurs within cyberspace, including through websites, online forums, social media, phone calls or online games, it’s referred to as online sexual violence.

Chong emphasizes that sexual connotations and nonconsent are two fundamental elements that define sexual violence. “Any behavior involving sexual connotations without the consent of another party can constitute sexual violence.”

To be specific, sexual violence could be in various forms, including violence through direct physical contact like rape and assault, nonphysical contact acts, such as voyeurism and sexual gazes, and even verbal action, such as making degrading comments about someone’s body. A victim subjected to pornographic jokes or repeatedly being asked out on dates on social media can also be considered as online sexual violence if they cause distress to a party involved, says Chong. She stresses that sexual violence isn’t restricted by gender, as both males and females can be offenders or victims. In addition, it can occur in any relationship, including intimate partnerships and marriages.

Chong stresses that sexual consent is a dynamic process that can be given and withdrawn at any point during a sexual encounter. Consent is also specific to a particular act and does not imply consent to any other sexual activity. For consent to be valid, it must be a fully conscious and voluntary decision, being given freely and autonomously without any form of pressure or manipulation.

Donna Wong Chui-ling, director of Against Child Abuse, which was set up in Hong Kong in 1979 as a charitable organization specializing in child protection, says the concept of sexual consent is often illusory in many cases of cyber sexual violence against children. For instance, in cases of online sexual grooming, perpetrators manipulate and deceive children to gain their trust before making sexual demands. The consent provided by children in such a situation is not genuine.

Acts of sexual violence against children also frequently involve a significant power imbalance. This could manifest as teachers or coaches exploiting their authority over students, or adults taking advantage of vulnerable minors. The inherent power differential makes it extremely challenging for children to decline sexual demands, leaving them coerced into giving consent.

Tip of the iceberg

Elia Yeung Man-wai, executive manager of the End Child Sexual Abuse Foundation, believes that the number of cases of online sexual violence given by the police may be just the tip of the iceberg.

Most incidents were exposed when family members stumbled upon evidence on a child’s phone. In some instances, children are threatened after someone has taken compromising photos of them, forcing them to seek help from teachers and parents. There are also cases of children unintentionally and mistakenly sharing explicit content on the internet with the wrong people, according to Yeung.

Victims who feel fear, shame or embarrassment may not reveal their plight voluntarily. Compounding the problem, many students lack a clear understanding of online sexual violence, resulting in many cases being unnoticed, even by the victims themselves.

Drawing from her experience in handling cases of sexual violence, Yeung estimates that up to 70 percent of such cases go unreported.

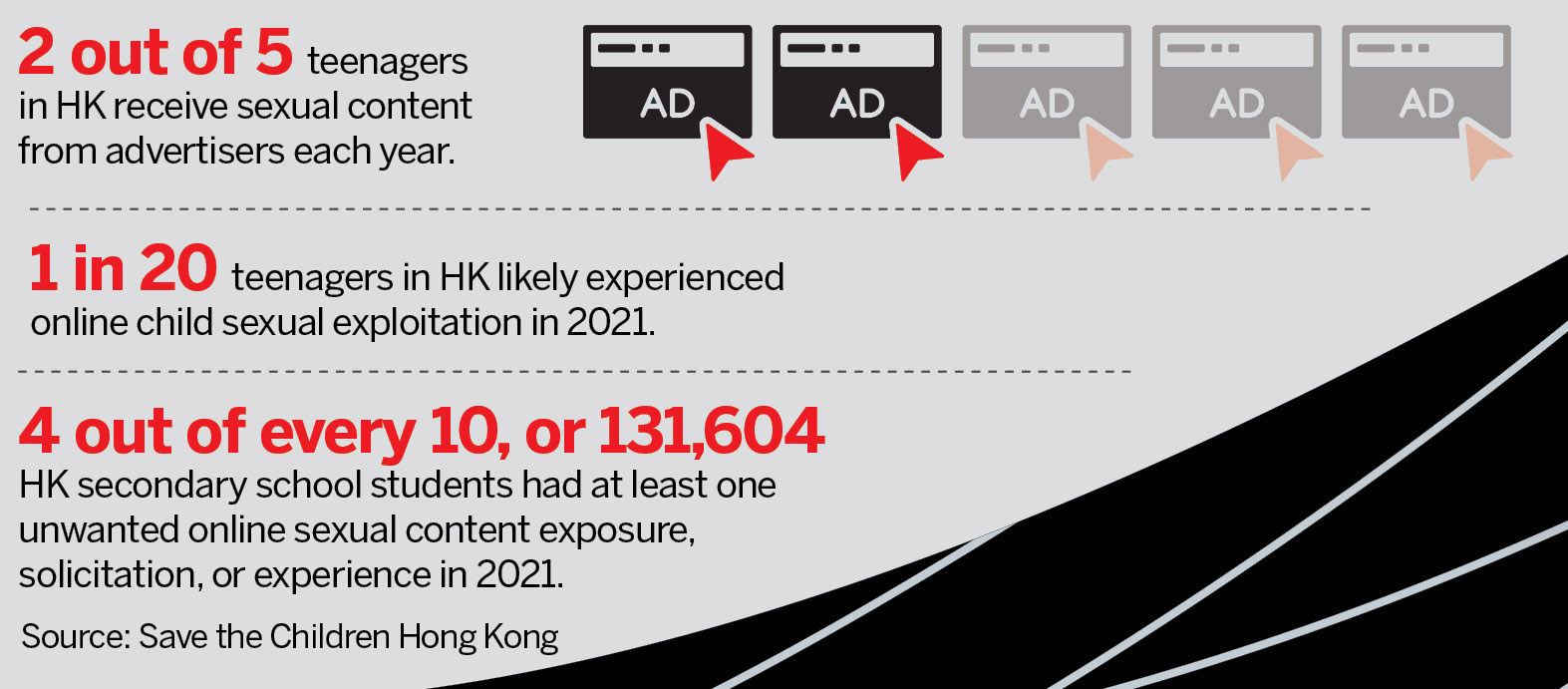

Carol Szeto, chief executive officer of Save the Children Hong Kong, says the rate of nonconsensual online sexual experiences among teenagers is alarmingly high.

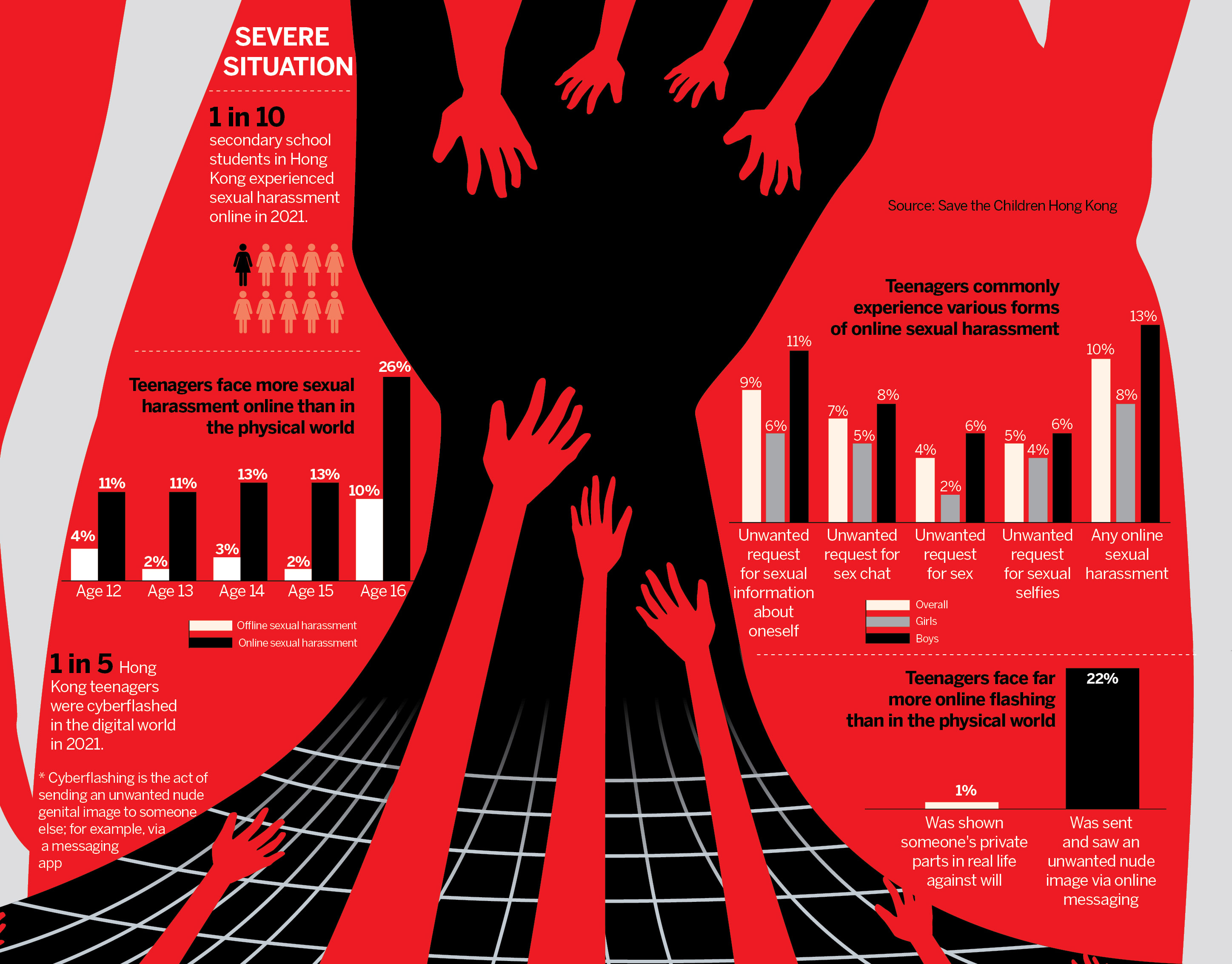

Based on a survey done by Save the Children Hong Kong in 2022, one out of every five teenagers encountered “cyberflashing”, which involves receiving unwanted sexual images on the internet. Approximately, one in 10 students had experienced online sexual harassment, while one in 20 had received requests to share explicit photos of themselves. Five percent of the respondents reported having been coerced into engaging in involuntary sexual acts online.

Reasons behind

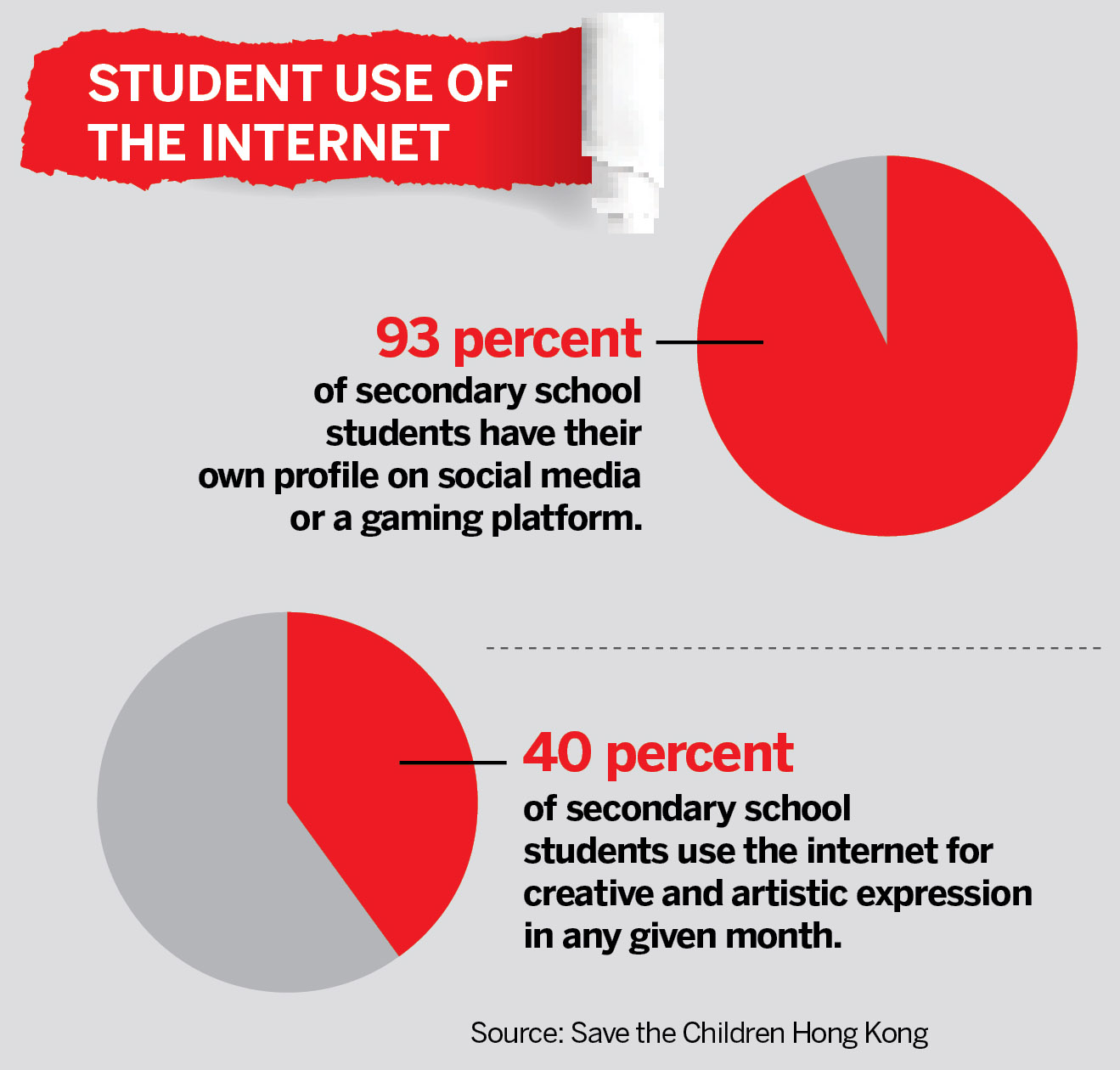

Szeto blames children’s growing reliance on the internet as the primary reason for the escalating trend of cyber sexual violence against them, with more than 70 percent of young people in Hong Kong owning a personal computer, and 94 percent having cellphones.

Li says that while the internet has made people’s lives more convenient, it has also helped abusers perpetrate malicious activities. The internet’s unrestricted availability has eliminated time and space boundaries, enabling sexual violence to occur 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Moreover, the nonlocal nature of abusers makes it difficult for the authorities to bring them to justice. The internet has rendered counterfeiting and payments easier, facilitating fraudulent and sexual transactions, says Li.

Research has shown that online sexual harassment among students surpasses that of real-life incidents by more than fourfold. While only 1 percent of young people have reported involuntarily encountering someone’s private parts in real life, the proportion reaches 22 percent in the cyberworld.

Another factor contributing to the cyber sexual violence trend is children’s lack of love and care in real-life situations, says Li.

A survey conducted by the PolyU professor identified two high-risk groups experiencing cyber sexual abuse — children with insufficient family attention and care, and those who are socially withdrawn.

This viewpoint is backed by a separate poll carried out by Save the Children Hong Kong, which found that adolescents who have experienced abuse or neglect are four times more likely to have been subjected to involuntary sexual abuse online, compared to the general population.

In Yeung’s view, there has been a prevailing sense of loneliness and increasing alienation in the community. With limited connections in real life, teenagers turn to the internet seeking comfort. Compared to the harshness of reality, the online world offers children an illusory sense of goodness where people are always perfect although there could be bigger dangers lurking, warns Yeung.

Inadequate education on sex and cybersecurity is another factor behind the cyber violence trend, says Yeung.

In some instances, it’s the children themselves who post pornographic materials online or share nude photos with others. At the same time, sexting has become quite common among young people, and it’s normal for teenagers to use pornographic materials to joke and tease each other.

In their adolescence, children undergo significant physiological and psychological changes and display curiosity about sex. Their sex-relevant behavior should not be stigmatized, but society should promote proper education on sexuality among teenagers. Failing to do so may lead to regrettable actions that may affect them for the rest of their lives, says Yeung.

Call for action

Chan believes that, due to a lack of awareness, many children may not understand the harm they have endured in their early years. However, as they become mature enough to engage in intimate relationships, the repercussions of the trauma can manifest in diverse ways, she says, adding that sexual violence online can inflict significant psychological and physical harm on children, such as depression and anxiety, low self-esteem, self-blame, social isolation and withdrawal.

Moreover, the peril of cyber sexual violence resides in its capacity to transition from online to offline scenarios. If online violence remains unaddressed, it’s very likely to spill over into real-life situations, escalating to sexual assault or, in the worst scenario, rape. This exacerbates the gravity of the issue at hand, says Chan.

In Wong’s opinion, students enduring violence should receive appropriate aid and psychological treatment. If their mental or physical harm is unresolved, they may internalize the violence, leading to a cycle where they might transform themselves from victims to perpetrators.

She emphasizes that Hong Kong’s efforts to combat cyber sexual violence primarily rely on existing laws to deal with offline sexual offenses, including the Prevention of Child Pornography Ordinance, the Sex Discrimination Ordinance, and certain provisions under the Crimes Ordinance.

Hong Kong took a step forward in 2021 by enacting the Crimes (Amendment) Ordinance, which identified specific offenses relating to sexual violence online, such as publishing intimate images or threatening to publish intimate images online without consent. Under the law, offenders may face up to five years’ imprisonment.

Despite the progress made, Hong Kong still lacks dedicated regulations to specifically deal with cyber sexual violence. Furthermore, a five-year jail term may not be a sufficient deterrent. Wong urges the SAR government to increase the punishment for perpetrators of cyber sexual violence against children.

Szeto calls for the setting up of an online safety commission — an independent body to coordinate help-seeking and complaint mechanisms and develop regulations, guidelines and public resources for digital safety.

She also suggests creating an anonymous hotline for reporting illegal online content, citing INHOPE as an example.

INHOPE is a global network of hotlines dedicated to combating online child sexual abuse material. With 54 hotlines operating in 50 countries and regions, excluding the Chinese mainland and the HKSAR, it enables the public to anonymously report such content. Trained analysts will review the reported materials and, if confirmed to be illegal, law enforcement agencies will be notified, and a notice and takedown order will be sent to the provider involved for the swift removal of the content.

Szeto says the SAR government can draw lessons from INHOPE’s operations.

According to Li, three key factors contribute to the occurrence of a crime from a criminological perspective — the potential victim, the guardian and the perpetrator. In the case of online child sexual abuse, apprehending the perpetrator is highly challenging. Therefore, the focus should be on strengthening potential victims’ ability to protect themselves and enhancing the guardian’s ability to ensure the safety of victims.

Thus, society should allocate more resources for sex education programs targeting guardians, including parents, teachers and social workers.

In Li’s view, sex education for potential victims, namely children, is the most fundamental measure to tackle sexual violence at its roots, and schools should allocate sufficient time for sex education to ensure that students receive comprehensive instructions.

Contact the writer at oasishu@chinadailyhk.com