Editor’s note: Water from the faraway Dongjiang River first surged through Hong Kong’s pipes six decades ago, quenching the thirst of a city on the rise. In this second HK Mosaic feature, China Daily traces how this life-giving flow helped propel a humble trading port into a glittering financial metropolis — a transformation written not just in steel and glass, but in the very water its people drink.

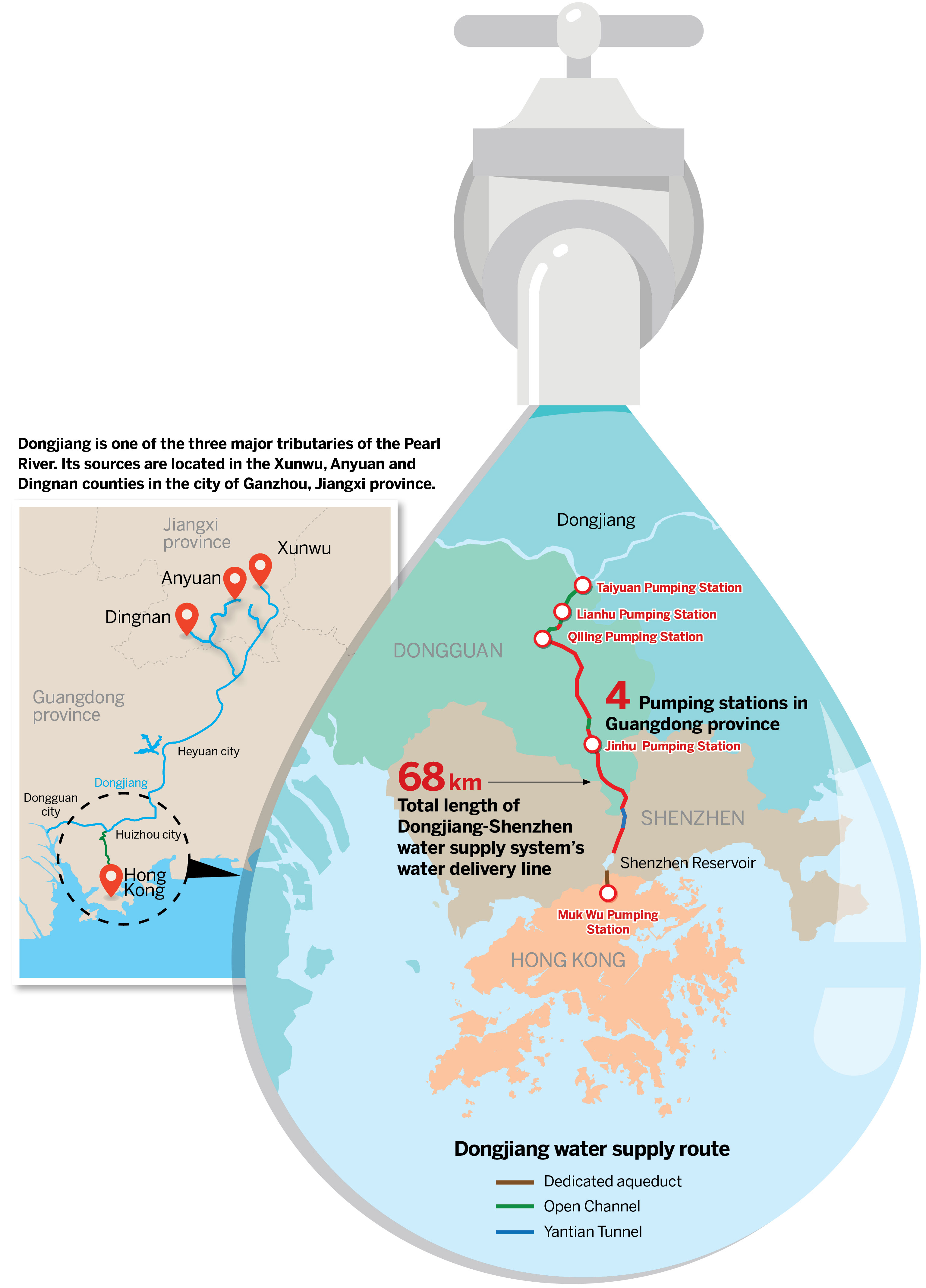

For six decades, Dongjiang water from the highlands of East China’s Jiangxi province has traversed mountains and valleys, reaching Hong Kong to quench its thirst and fuel the city’s emergence as one of the world’s premier financial hubs.

The sheer volume of water delivered to Hong Kong had exceeded 30.1 billion cubic meters by March 31 — enough to fill Hangzhou’s West Lake 2,100 times and sustain a metropolis that has risen from post-war scarcity to become an economic marvel.

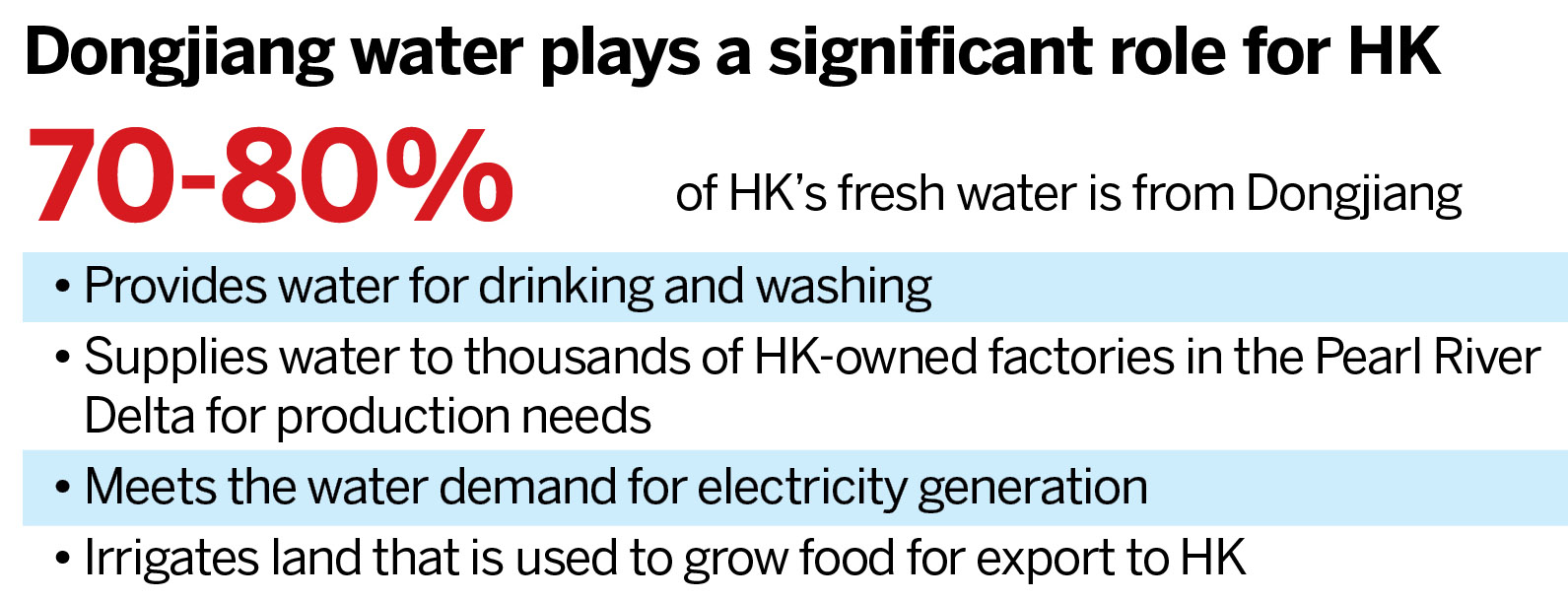

Today, the Dongjiang River feeds the special administrative region with up to 80 percent of its potable water — a lifeline that officials and development experts say has contributed to Hong Kong’s economic and population boom, and secured its place among Asia’s “Four Tigers” in the second half of the 20th century.

READ MORE: CE: Dongjiang water supply to HK ensures city's sustained growth

“Without Dongjiang water, Hong Kong wouldn’t be what it is today,” says Hamanth Kasan, president of the International Water Association.

He calls the project a “great system” that has propelled Hong Kong’s rise in the past 60 years.

Historic collaboration

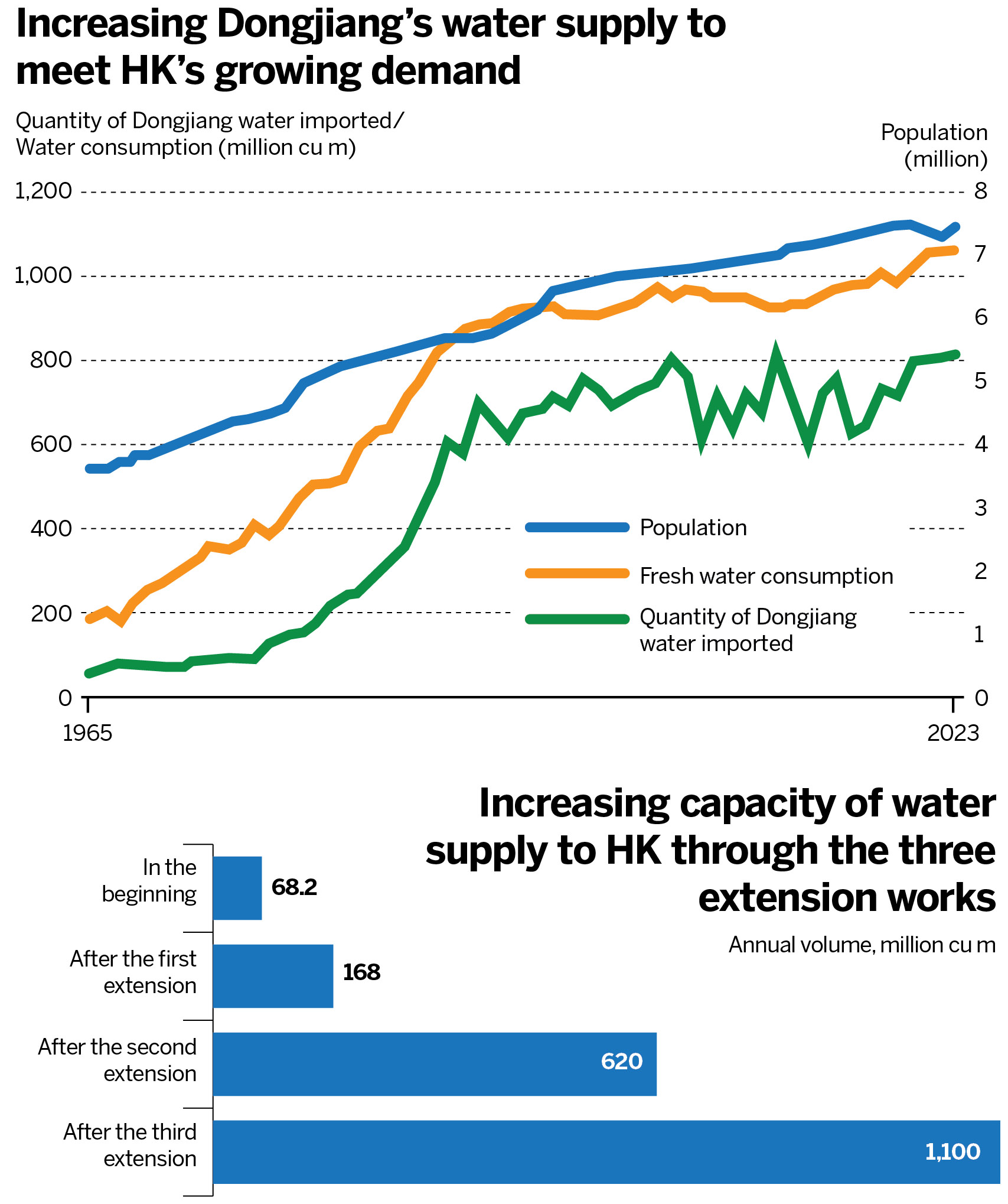

The figures speak volumes — Hong Kong’s gross domestic product having grown more than 266 times since 1965 when Dongjiang water began flowing across the boundary. The annual water supply ceiling was raised from 68.2 million cubic meters to 820 million cubic meters as Hong Kong’s population skyrocketed from 3.6 million to over 7.5 million.

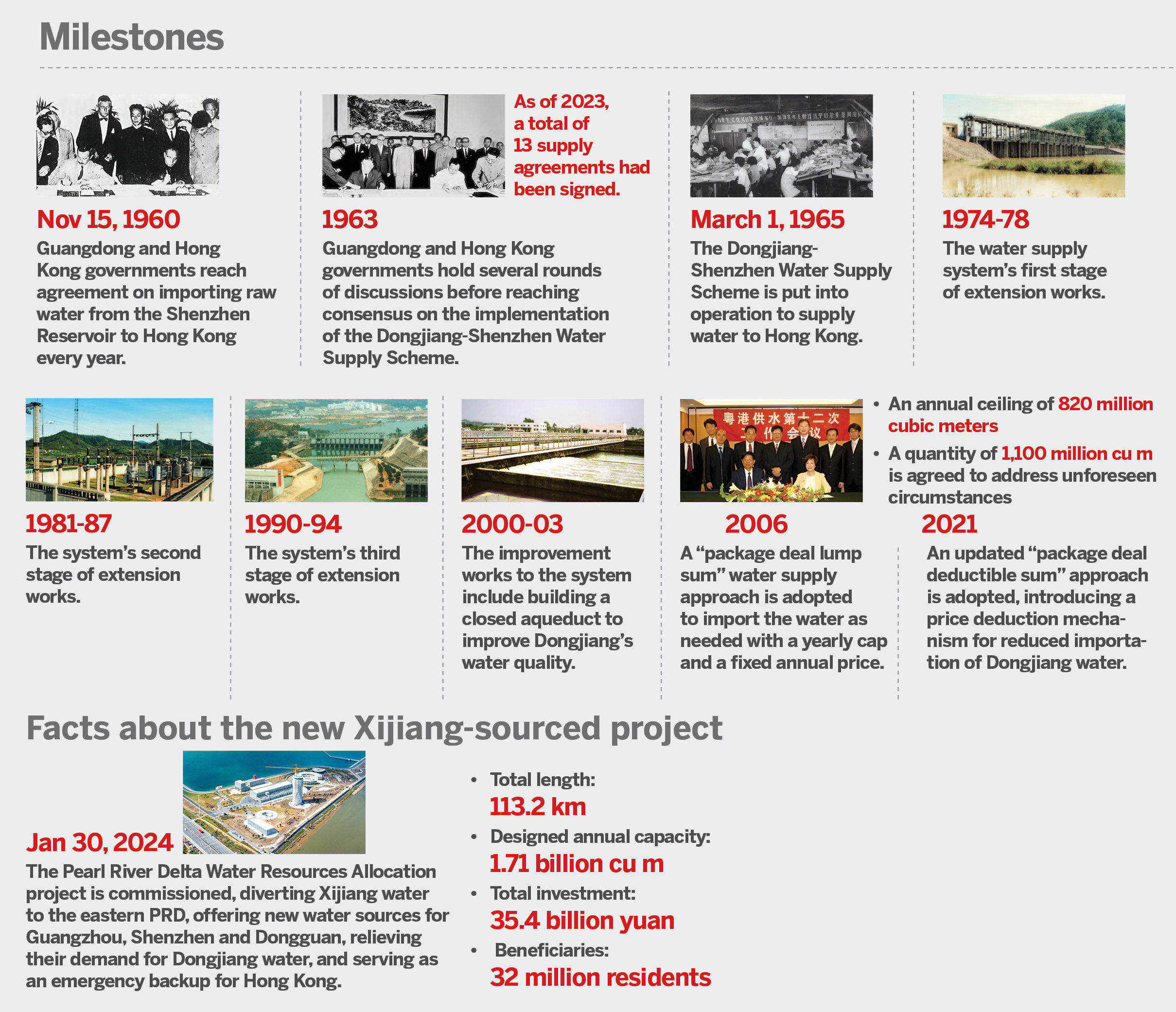

In the face of fluctuating rainwater reserves and explosive population growth in the 1960s, Hong Kong turned to its neighbor, Guangdong province, for help. Both sides first struck a deal in 1960, with Hong Kong purchasing 22.7 million cubic meters of fresh water each year from Shenzhen Reservoir. However, the arrangement failed to help the city tide over a destructive drought three years later.

The 1963 drought paralyzed Hong Kong, forcing three million residents to subsist on just four hours of running water every 96 hours, creating long queues of people with buckets at communal taps.

“While I have never faced those extreme conditions, I still remember those childhood frustrations when taps ran dry for hours at a time,” reminisces Secretary for the Civil Service Ingrid Yeung Ho Poi-yan, who was born in the drought’s aftermath in 1965. “Even temporary shortages caused significant hardship.”

The chaotic scenes prompted action by the central government to fund and supervise the construction of an extensive water network across Guangdong’s challenging landscape — the Dongjiang-Shenzhen Water Supply project. The goal was to channel water from Dong-jiang River over 50 kilometers away to meet Hong Kong’s critical needs.

‘Engineering triumph’

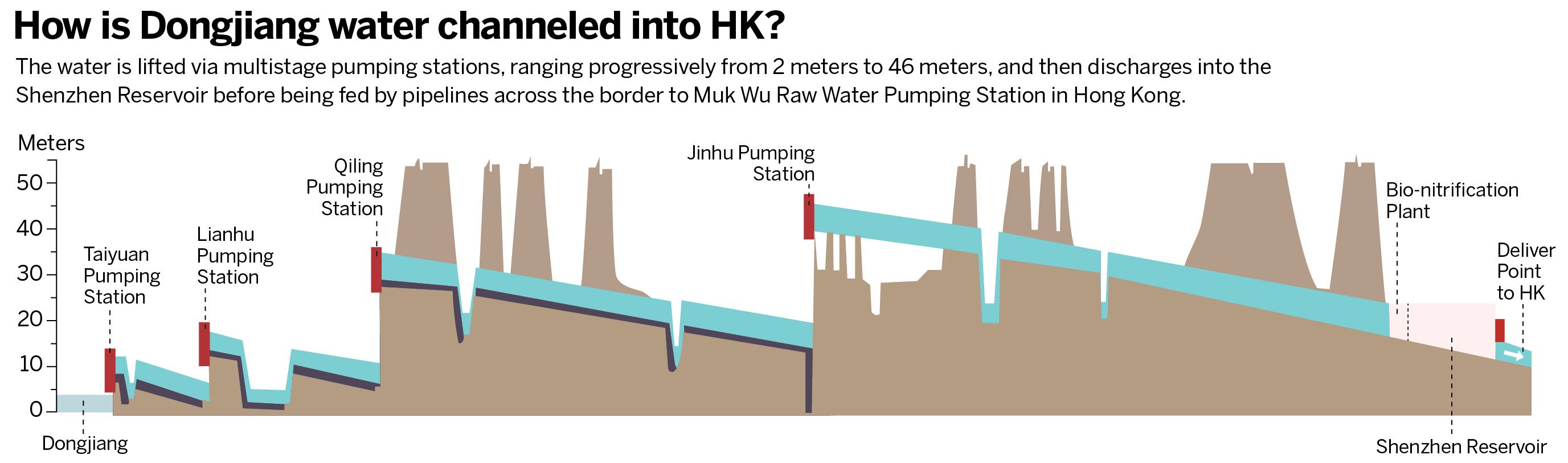

Armed with basic tools, a workforce of more than 10,000 Chinese mainland laborers achieved the extraordinary by constructing an 83-kilometer pipeline system through rugged terrain, complete with multiple pumping stations — all within a year. The water was pumped and lifted by 46 meters, and had to wind through six mountains before being injected into Shenzhen Reservoir. At 4 pm on March 1, 1965, the network began operation, adding momentum to Hong Kong’s emergence as the “Pearl of the Orient”.

Speaking at the International Water Pioneers Summit 2025 last month, Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu hailed the project, which has been upgraded multiple times to meet Hong Kong’s escalating needs, as an “engineering triumph” in the early days of the People’s Republic of China.

This feat — and the water it provides — would not have been possible, certainly not in the 1960s, had it not been for the strong bonds and shared blood relations between Hong Kong and the mainland, he said, adding that the supply has accelerated Hong Kong’s economic progress, underpinning its sustainable development and long-term prosperity.

Development experts call the water infrastructure a cornerstone of Hong Kong’s late-20th-century economic achievements, enabling its rise as one of Asia’s “Four Tigers”, but warned of the limits to increasing supply.

Dragan Savic, a hydro-informatics professor at the University of Exeter, says the project has been key to Hong Kong’s rapid development by raising the water supply volume 12-fold over six decades.

Today, Hong Kong reservoirs’ total storage capacity stands at nearly 600 million cubic meters, against an annual average water consumption rate of about 1.7 million cubic meters.

“In the future, we have to balance that a bit with better management,” says Savic, referring to the adoption of water treatment and smart distribution technologies.

Dongjiang River also has to sustain tens of millions of people across Guangdong’s megacities — from Guangzhou to Shenzhen. Yet, the province operates on a knife edge — just 1,100 cubic meters per capita annually — barely above the international severe water stress threshold of 1,000 cubic meters.

Despite having to support nine percent of the country’s population with only 6.5 percent of its water and generating 10 percent of the gross national product, the authorities have always prioritized Hong Kong’s supply.

“Even during chronic water shortages, one principle is upheld — Hong Kong’s allocation stays untouched,” says Zheng Hangwei, chairman of Guangdong Yuehai water supply company.

The ultimate test came with the 2020-22 drought and the COVID-19 pandemic disruptions. Yet, over 800 million cubic meters still flows annually into the city.

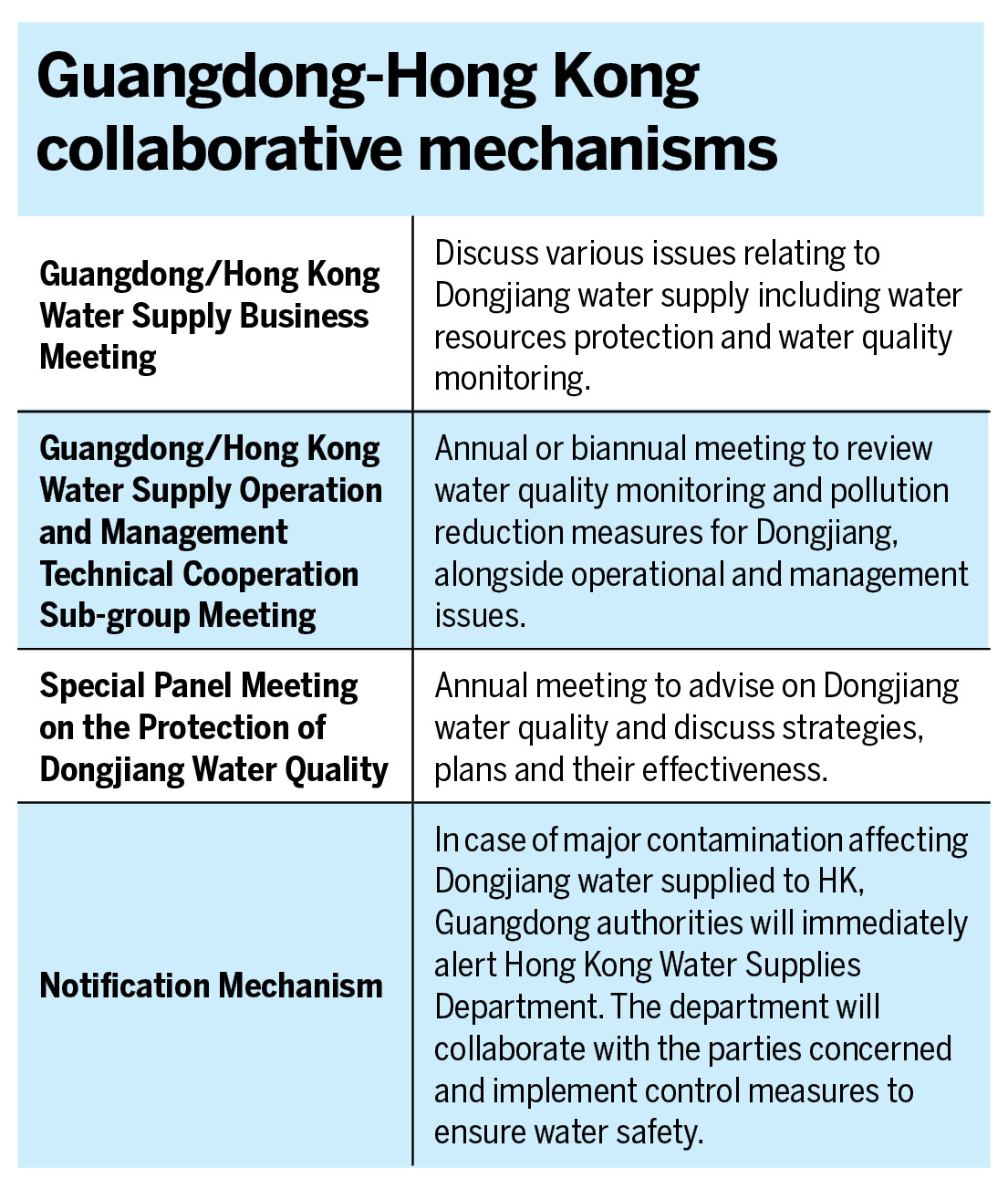

Lee noted that Hong Kong residents’ trust in Dongjiang water stems from its consistent quality that meets the country’s highest national standards for potable water sources.

Upstream sacrifices

Supplying Hong Kong with Dongjiang water demands major sacrifices from upstream communities. In Heyuan city, Guangdong province, where the azure Xinfengjiang Reservoir contributes 15 percent of the Dongjiang water flow, the local authorities had to scrap more than 500 industrial projects worth 60 billion yuan ($8.23 billion) to protect the quality of the water.

The story was repeated across Guangdong and Jiangxi. Villages had to restrict farming, entire communities had to relocate, towns turned down factories, and families watched economic opportunities flow downstream with the water they safeguard. Yet, many residents find pride in making these sacrifices — measured not in GDP, but in the crystal clear reservoirs sustaining millions of Hong Kong compatriots.

Guardians’ pride

Zhong Sheng grew up beneath Sanbai Mountain in Jiangxi’s Anyuan county, where Dongjiang River originates. Throughout his childhood — in classrooms, television programs and local sayings — one lesson has remained constant: “Of Jiangxi’s countless rivers, only the Dongjiang flows south to Boluo.” — a Guangdong county that channels water to Hong Kong.

“We have always cherished our role in nourishing Hong Kong,” says the 47-year-old educator.

In 2023, Zhong became principal of Siyuan Experimental School, established in 2015 with funding from a Hong Kong foundation. The school’s name (“Remember the Source”) embodies its environmental mission and the deep bonds forged with Dongjiang water. Through annual tree-planting initiatives and watershed cleanups, the school’s 4,000-plus students have learned their vital role in protecting the Dongjiang River that supports millions of people downstream.

Zhong still remembers the starkly different landscape decades ago with barren hills stripped for firewood and streams choked with plastic. Today, rigorous conservation efforts have restored the ecosystem, a transformation locals attribute to their sacred duty as Dong-jiang’s guardians.

“After six decades, Dongjiang water remains pure,” he says.

For nearly 10 years, Lai Jinshan has trekked the rugged slopes of Sanbai Mountain, serving as a protector and healer of its forests’ ecosystem. His days are spent mapping rare trees, nursing endangered plants back to health and last, but not least, ensuring the purity of the mountain’s headwaters.

During the monsoon season, decaying branches and debris would choke the mountain streams, threatening aquatic life and increasing the risk of landslides. In April 2018, after a violent storm, Lai recalled wading into freezing, waist-deep currents to clear a clogged waterway. Despite being soaked and later bedridden with fever, he was back on patrol at first light the next day.

ALSO READ: Officials hail Dongjiang water as vital lifeline for Hong Kong

“Clean water and healthy forests make every hardship worthwhile,” he says.

In a social media post, Yeung, who has lived through Hong Kong’s water-scarce past, stressed that public understanding of Dongjiang water’s crucial role in maintaining the city’s economic growth and basic living needs is paramount, especially for the younger generation.

“If it weren’t for the continuous supply of Dongjiang water, it’s hard to imagine what our lives would be like today.”

lilei@chinadailyhk.com